Documentation of the Impakt Festival will be posted here soon, but as a start here’s a report on the conference, written by Elena Tiis.

Sitting in the plush, red chairs at Filmtheater ‘t Hoogt in Utrecht on the 15th of October, I listened in to the lectures of the “Accelerated Living” conference dealing with the ecologies of time & speed, and media technologies’ capacity to impact contemporary time experience.

The kick off was with John Tomlinson’s (UK; Professor of Cultural Sociology and Director of the Institute for Cultural Analysis, Nottingham) lecture on the culture of speed. Taking a broadly historical approach to what speed is, Tomlinson describes it as a condition of immediacy, a most spectacular transaction between time and space, that Marx describes as the “annihilation of space with time” (Grundrisse). Speed in general is under-researched; it fades from view in considerations of modernity, except for Virilio to an extent. Marinetti in “The Futurist Manifesto” talks about omnipresent speed, about capturing in art countercultural appropriations of speed. Interestingly, Tomlinson characterises Le Corbusier as a mainstream version of speed appropriation because the Swiss talked how a “city made for speed is a city made for success”, imagining how the speedways of the Voisin plan would serve businessnessmen as they swished to and from work. This type of speed was the mechanical, physical speed that could putatively transform the whole world.

Contemporary “fast capitalism” is facilitated by ICTs. The integration of media is a key dynamic for understanding of how this type of fast speed works, how it leads to the general increase of intensity and mobility. High speed speculative activity has the capacity to induce crisis.

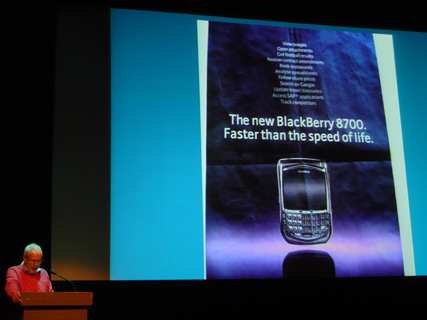

To characterise this condition of fast capitalism, Thomlinson introduces the concept of “immediacy”, which is instant/has no lapse and proximate/close. It is a quality of cultural experience, containing a new sense of compulsion in life – that of communicational imperative or demand. To this effect, he treats a Blackberry ad as Derrida’s pharmacon – both a poison and a cure – because it is useful for both work and leisure. It also signals the bleeding of work-related emails outside of work hours, in a Marxist sense this is exploitative because these emails come to constitute unpaid labour, but on the other hand it has the advantage of being flexible. Consumers often start facing the burden of service, for instance they are required to buy their own plain tickets, to check in, to selecting seats etc. all of which demands their time.

The second major concept that Tomlinson introduces is “legerdemain” or lightness of hand. In the first sense, it is the body-work of touchpads and keyboards that seems effortless, something like gesturing as opposed to real work. This lightness has the capacity of bringing with it associations of immediate accessibility. In the second sense, it is a world of illusion and delusion, like a type of magic that conceals and deceives; the interface is hiding the complexity of the whole.

The baseline promise of immediacy is that “stuff arrives”, and in the manner of a cargo cult consumer use attains a casualness and even thoughtlessness. Finally, there are political and environmental costs to all of this because these media do not penetrate everywhere and are not accessible by anyone. There is also a sense that there is no broader narrative for current features of speed, unlike during the machine age when a strong narrative of speed operated on the assumption that there are disjunctions between home/abroad, now/later and desire/fulfilment. Now there is no gap to close so there is narrative of closure. To conclude, Tomlinson argues for the importance of ensuring that distinctions do not collapse and that one must keep in view the sight that there are broad, cultural-political reasons for us doing what we do.

Mike Crang’s (UK; Lecturer in Cultural Geography at Durham University) more geographically inflected take on spatial and temporal reach examines how to combine the fragmentary pattern of speeds and scales on different places. One must not forget extension, or the spatial distanciation of multiple temporalities. New technical possibilities shape world spaces where “bits [are] over borders”, where patterns of flows are connecting across physical boundaries. Crang showcases various examples of mapping these new realms, e.g. NYTE who map global conversation space from the perspective of New York. (http://senseable.mit.edu/nyte/)

He also emphasises the usefulness of drawing out Virilio’s dromo-chrono-politics, which is a way of collapsing distinctions that puts forward the question: what type of governance for ICTs?

GAWC’s world city index maps the propinquity of cities based on the shape of their communications and flight connections, showing that even these new forms build on old connectivities, especially those of colonial origins. One can also talk of the production of centrality, for instance when hub airports become gateways like in the case of the Helsinki – of itself it is not a big airport, but by virtue of its good Far East connectivity it can characterise itself as a major gate. Sekula also notes that we must not forget the sea as transport space: most global steamer routes haven’t changed much in fact, and these are mostly how as Tomlinson would put it “stuff arrives” as if by magic.

Crang devotes some time to the space of chronopolitics. This is to mean the way in which cities “shut down” at different times; time, in fact, is populated by different chronopolitical topographies. Crang proposes a typology of spatial and temporal fixings, which also involve social coercion. Flexible space involves trading on the real spaces of poor countries, for instance when New York time is transposed to Hyderabad where employees must use various locational masking techniques –

as well as working at inconvenient times of day – in order to service their employer.

Next, Carmen Leccardi (IT; Professor of Cultural Sociology at the University of Milan-Bicocca) takes a broadly philosophical approach to the restructuring of time. Her key terms are detemporalisation and acceleration society, which she compliments by a consideration of the ways in which “young people” bring into being new notions of time by engaging in anti-globalisation movements and new ways of constructing biographies. Taking her cue from Rosa, Leccardi defines acceleration society according to its three motors – economic (profit driven, neoliberal), cultural (need for experiences) and structural (rhythms of social change). Aside from this, it encompasses three levels: technological, political meaning and the role of social change, what she conceives of as the different meanings of institutions (which could constitute a point of contention because one might want to keep an analytical distance from the meaning of social change and institutional realities). Rosa’s “acceleration society” traces how technological acceleration means that time is growing in scarcity which manifests as a contradiction shaping our lives. Thus, how can we build civic space?

Leccardi spends time on the reconsideration of the idea of the future. Lübbe’s monster term of “Gegenwartsschrumpfung” – the contraction of the present – means that the present is not available for use and one must rely on the future for conceptual package. The building of identities in this interface is challenging, as it is the situation in question and not the over-all life-plan that matters in the end. Again, there might be some rigidity in Leccardi’s notion of these two; she seems to think of them in terms of their reflection in institutions and as their own separate spheres which tend not to interact.

Her guiding term “detemporalisation” means that time loses the character of being a dimension of experience, that the sense of duration is reshaped and operates in relation to the future. The unpredictability of the future is making life-plans irrelevant, therefore the “young people” of today are rather learning to act flexibly and contingently. She enlists two examples of this. First, antiglobalisation movements are resisting the violence of time/space commodification, think in terms of values and re-establish the connection between cause and effect in what is happening. The second feature are biographical constructions, which are concerned with mediating unpredictability and developing responses that neutralise fears of the future. I think that there might be more flexible ways of considering how notions of time are changing than simply from institutionalised to a non-life-plan. Be that as it may, Leccardi rounds up the first session of general introductions to the notions of speed from the perspectives of different academic disciplines.

After lunch, there is a change of moderation as well as an inexplicable change in the order of the talks. Stamatia Portanova speaks before Steve Goodman, who, due to the moderator’s confusion about the timeframes had his lecture cut tantalisingly short. This session begins to showcase talks of more specific inflection – as concerns choreography, music and visual perception.

Stamatia Portanova’s (IT; PhD in Digital Cultures at East London University) talk proposes a redefinition of the digital age as a neo-Baroque age. Her dense, dextrous presentation dealt with Bifo’s manifesto for a postfuturist age (http://eipcp.net/n/1234779255?lid=1234779848). Using futurist notions of time and movement as points of departure, she investigates more corporate conceptions of rhythm and topography. Movement is a sensation not a perception. Sensation is a vibratory wave crossing through bodies. As the body becomes a framer of spatial information in media interface, the liberation of the body is a biophilosophy that turns towards the affect, or embodied aesthetics. Intensity is understood as Deleuzian desire; an energy that is in itself and not for something. Aesthetic style with its technological present is controlling the body possible and creating a different ontology: Deleuzian desire and ICTs interfacing in the creation of energy as information. The digital is an idea, a concept before becoming reality. In this it is attuned to the Baroque in its striving for dissection, for a microscopic notion particles and the technological idea of the cut. Portanova’s contention is that we can find an openness in technology that is not only dependent on the imitation of life. Chronological and metric notions of time can allow us to imagine an infinite succession of time that is alive.

Steve Goodman’s (UK; teaches Sonic Cultures at East London University) talk was badly interrupted, so the promised exposition of the concept of speed tribes and the development of music cultures did not manifest. Even so, his brief talk was beautifully evocative of the forthcoming book “Sonic Warfare” (2009). Like Portanova, he begins by departing from Bifo’s provocation; how is it possible that futurism could become passé? He proposes a consideration sonic ecology, the competing corporate and grassroots initiatives in contemporary sonic culture. By contrasting futurism with afrofuturism, he is tracing the things that could be retained of futurism. Afrofuturism presents more complex ideas of speed than futurism’s god of speed. The sonic warfare concept is evoking the art of war in the art of noise. Afrofuturism is a colonised culture’s way of striking back through sound. As expounded by Kodwo Eshun in his “More Brilliant Than The Sun” (1997), it is a nexus of black musical expression, the city and the cybernetic in electronic music. Eshun’s concept of the future rhythm machine evokes the sensual mathematics of music as non-conscious counting. Afrofuturism is rewiring alienated experience through urban machine musics, presenting a landscape that extends into possibility space. Simon Reynolds’ description of the dystopic metropolis of warrior clans and robber corporations creating a city as a warzone and ecologies of dread in the 90s wanted to examine the intersection of underdevelopment, technology and race in the city, thus attains a different type of futurity. In contrast to Marinetti’s and Russolo’s unilinear notion of history with its white metallicist Übermensch, Eshun’s afrofuturism is polyrhythmnic, bred from cyclical discontinuity, aligning the future paradoxically. In the intersection of roots and futurism, memories are those of the future – the future scifi alien abduction actually happened in the past when black people were subjected to slavery! According to this, the sonic avant-garde of high modernism were actually afraid of rhythm. At this point, Goodman is forces to “skip about 20 pages” and concludes that in view of corporate co-option of musics, afrofuturism is not necessarily scifi but has proliferated as something that – aside from selling record – has the capability of affectively mobilise people.

Dirk de Bruyn’s (NL/AU; Senior Lecturer in Animation and Digital Culture at Deakin University, Melbourne) lecture dealt with the “after-image as a traumatic event” by using Prensky’s distinction between digital natives and digital immigrants as a way of tracing out inherencies in the way that people tend to interact with the medium and Brewin’s notions of VAM (verbally accessible memory) which deals with the context and SAM (situationally accessible memory) which deals with perception. These always intermix; the categories are not useful so rigidly. Flusser’s notion that “we all are immigrants now” repositions the migrant experience as that of globalisation itself. This has impact on our relation to technical literacy: we remain illiterate if not engaging in criticism of technical images. The issue is about how to critique technologically mediated images on their own terms, by the realignment of senses as in the case of the perceptual apparatus adjusting and sometimes fooling the viewer.

The final session could be said to attain to a type of microspecificity, first in relation to maps in video games such as Civilisation and Charlie Gere’s talk which managed not to consider nothing related to digital media, or the 21st century for that matter. This was followed by a presentation of two artworks by two British artists operating in the ambiguous interface between visual art and online media.

Sybille Lammes (NL; Assistant Professor of Media and Culture Studies at Utrecht University) spoke of gameplay and digital ludic cartographies. In particular, she explored the changeable status of minimaps in gameplay with recourse to De Certeau’s and Latour’s concepts. Is there something at stake in what games do to analogue maps? De Certeau’s notion of spatial stories – of touring – contrasts with the rigidity of mapping especially after the Renaissance period. In the middle age, the two senses were fuse: a map would show a place as well as an “experience” or a perception of it. Such touring traces are performative iterations. In games, minimaps are looked at and altered by the player as a way of exploring vast spaces. Further, Latour’s “immutable mobiles” concept provides a way of describing the image as technology: it can be moved around but still depends on inscription. The player is a mediator, mutating the map by tactically interacting with space but also constantly erasing earlier versions, or inscriptions.

Charlier Gere (UK; teaches New Media Research at the Institute for Cultural Research, Lancaster University), for the whole of his lecture on ecology and messianic time, did not address much of anything to do with new media. In stead, his concern was to trace out Ruskin’s complex relationship with environmental issues to the point of the latter’s positive theophany of nature. In his soi-disant “vicar mode”, Gere was continuously on the verge of getting utterly distracted by long quotes from Ruskin peppered by autobiographical jabs at the author’s many odditities and failings. This domain-bridging presentation dealt with an eschatological mode of experiencing nature, through Ruskin’s description of the “messianic/apocalyptic” storm cloud of the 19th century. Via references to Derrida’s spectrality, or the reproducible virtuality of technology, to Agamben’s political ecology of messianic time in reference to Pauline notions of it, he ends up with images of the mushroom cloud over Hiroshima (the flash of the bomb took “photos”) to Tsernobyl’s radioactive fallout, arguing that invisible radiation is the storm cloud of the 20th century; its messianic narrative. At the end of this complex, flighty and quoty exposition I was left wondering where it is that we are then at the beginning of the 21st century – there are still about 90 years to think up/bring about the apocalyptic storm cloud of digital media and environmental depletion.

To conclude the day, artists Jon Thomson and Alison Craighead (UK) showcased two pieces of their work which deal with data by attempting to represent its two facets: the procuring information and the contrast between live and dead data. The exploration of the materiality of their material is at the crux of their endeavours.

* Beacon takes a live stream from search engines, functioning as a “useless clock”, portrait and a landscape whilst also managing to reveal a particular type of intimacy in people dealing with a search engine.

* A Short Film About War (part of Desktop Documentaries) is a collation of Flickr images and log texts accompanied by blog pieces spoken out loud. The film scrutinises the browsing experience and mediatic war through the net (web 2.0), especially by the use of Collective Commons images. The act of editorial becomes a sort of surrogate browsing experience for this collation of multiple strands of images and stories of war.

image: John Tomlinson