“Today, some people think that the light of the atom bomb will change the concept of painting once and for all. The eyes that actually saw the light melted out of sheer ecstasy. For one instant, everybody was the same color. It made angels out of everybody.”

Willem de Kooning on the radical visuality unleashed by the atomic bomb (1951)

Paul Virilio. War and Cinema: The Logistics of Perception (1989)

“The development of ‘secret’ weapons, such as the ‘flying bomb’ and stratospheric rockets, laid the basis for cruise and intercontinental missiles, as well as for those invisible weapons which, by using various rays, made visible not only what lay over the horizon, or was hidden by night , but what did not or did not yet exist. Here we can see the strategic fiction of the need for armaments relying on atomic radiation – a fiction which, at the end of the war, led to the ‘ultimate weapon’.

(..) Many epilogues have been written about the nuclear explosions of 6 and 9 August 1945, but few have pointed out that the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki were light-weapons that prefigured the enhanced-radiation neutron bomb, the directed-beam laser weapons, and the charged-particle guns currently under development. Moreover, a number of Hiroshima survivors have reported that, shortly after it was detonated, they thought it was a magnesium bomb of unimagined power.

The first bomb, set to go off at a height of some five hundred metres, produced a nuclear flash which lasted one fifteen-millionth of a second, and whose brightness penetrated every building down to the cellars. It left its imprint on stone walls, changing their apparent colour through the fusion of certain minerals, although protected surfaces remained curiously unaltered. The same was the case with clothing and bodies, where kimono patterns were tattooed on the victims’ flesh. If photography, according to its inventor Nicephore Niepce, was simply a method of engraving with light, where bodies inscribed their traces by virtue of their own luminosity, nuclear weapons inherited both the darkroom of Niepce and Daguerre and the military search light. What appears in the heart of darkrooms is no longer a luminous out line but a shadow, one which sometimes , as in Hiroshima, is carried to the depths of cellars and vaults. The Japanese shadows are inscribed not, as in former times , on the screens of a shadow puppet theatre but on a new screen, the walls of the city.”

Akira Mizuta Lippit. Atomic Light (Shadow Optics) (2005)

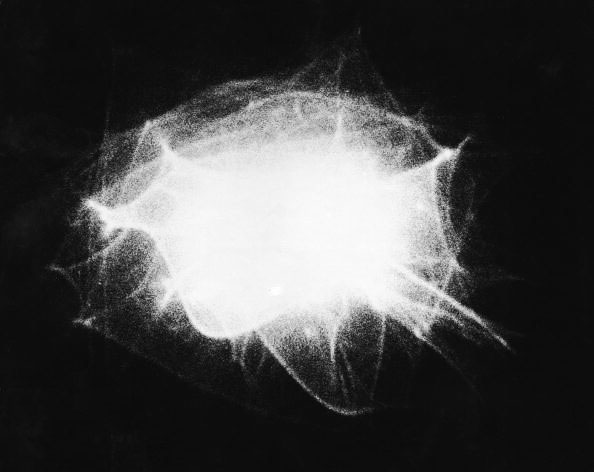

“What was intimated in the radioactive culture of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries erupted at full force in Hiroshima and Nagasaki: if the atomic blasts and blackened skies can be thought of as massive cameras, then the victims of this dark atomic room can be seen as photographic effects. Seared organic and nonorganic matter left dark stains, opaque artefacts of once vital bodies, on the pavements and other surfaces of this grotesque theater. The “shadows”, as they were called, are actually photograms, images formed by the direct exposure of objects on photographic surfaces. Photographic sculptures. True photographs, more photographic than photographic images.

(…) There can be no authentic photography of atomic war because the bombings were themselves a form of total photography that exceeded the economies of representation, testing the very visibility of the visual. Only a negative photography is possible in the atomic arena, a skiagraphy, a shadow photography. the shadow of photography. By positing the spectator within the frames of an annihilating image, an image of annihilation, but also the annihilation of images, no one survives, nothing remains: “it made angels out of everybody.”

(…) The catastrophic flashes followed by a dense darkness transformed Hiroshima and Nagasaki into photographic laboratories, leaving countless traces of photographic and skiagraphic imprints on the landscape, on organic and nonorganic bodies alike. The world a camera, everything in it photographed. Total visibility for an instant and in an instant everything rendered photographic, ecstatic, to use Willem de Kooning’s expression, inside out.The grotesque shadows and stains – graphic effects of the lacerating heat and penetrating light – the only remnants of virtual annihilation.

(…) In the remainder, a dark writing was born. A secret writing, written in the dark, with darkness itself. In the atomic night and on the human surface, a dark, corporeal surface appeared.”

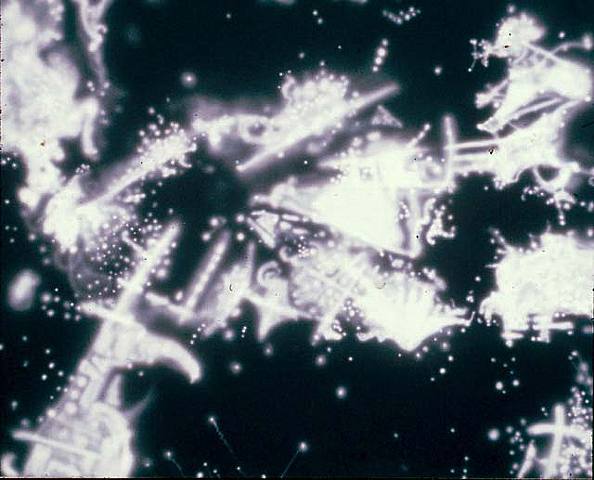

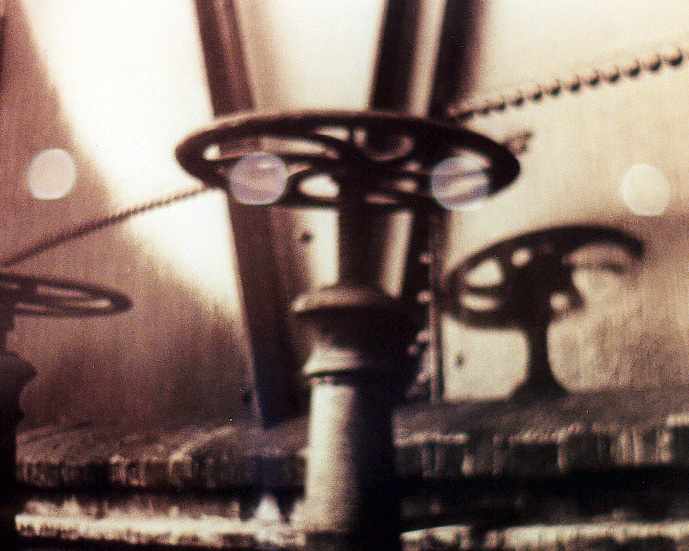

Below: documentation of ‘The Origin of Painting’ by Disinformation (Joe Banks) – luminous graffiti, live electromagnetic sound and shadow photography, autodestructive portraiture and experimental painting installation – a piece we’d like to show on the ‘night vision’ event (Courtisane Festival, March 18-21)