YES, it’s that time of the year again. The 2010 edition of the Courtisane festival will take place from March 17th till 21st, on several locations in Gent.

As always, Courtisane 2010 will present a broad selection of recent Belgian and international film and video works, bringing together an exciting mix of up and coming young talent and established names. On top of that, two thematic evenings will be filled with performances, installations and screenings. Thursday 18th March will be devoted to ‘Night Vision’, exploring the dynamics between visibility and invisibility, light and darkness, seeing the night and seeing in the night, with among others Paul Clipson & William Fowler Collins, Phantom Limb & Earth’s Hypnagogia, Disinformation and Pieter Geenen. ‘Surface Tension’, on Friday 19th March, has Dominique Petitgand, Karen Mirza & Brad Butler & David Cunningham and Paul Abbott with Seymour Wright & Ross Lambert investigating the folds and fissures between perception and conscience, experience and meaning. This year we have three “Artists in Focus”: David O’Reilly, rising star in the animation community, Morgan Fisher, whose work sits between avant-garde cinema, film industry and contemporary art, and David Gatten, who explores the intersection of the printed word and the moving image. ‘Digest Sound’, the exhibition, focuses on the sometimes successful, sometimes failing marriage between communication and technology, featuring work by Matt O’dell, Barry Hale & Joe Banks. The limits of communication will also be subject of the programme ‘Vital Signs’, with films and videos by Katarina Zdjelar, Gary Hill, David Gatten and many others. Our friends from KRAAK will also present a series of concerts during the festival. Get a foretaste with Carlos Giffoni and Oneohtrix Point Never on March 14th !

What follows is a kind of informal and incomplete preview of what’s coming. If you want to be kept up to date, please go to www.courtisane.be, or just keep checking this blog.

EVENTS

Night Vision (Thursday March 18th)

Paul Clipson & William Fowler Collins

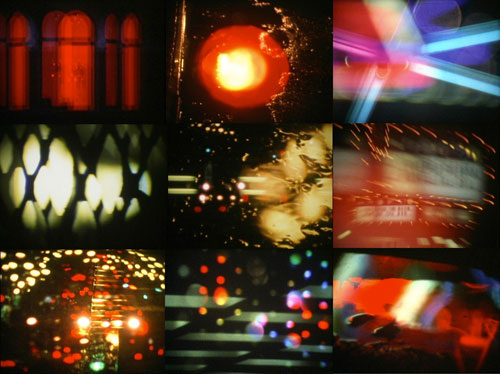

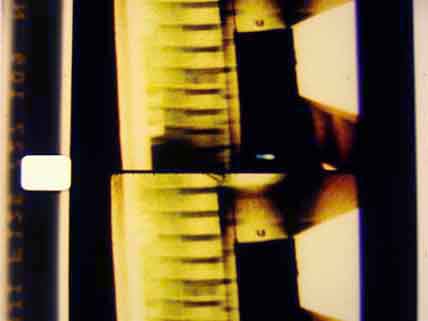

Paul Clipson’s Super 8mm films are shot and largely edited “in-camera”, in an improvised manner that brings to light subconscious preoccupations in the hope of allowing for un-thought, unexpected visual elements to reveal themselves. He often works in collaboration with experimental music and sound artists, exhibiting his work in live performance, screenings and installation. On the occasion of the Courtisane festival he will present a new piece, consisting of night footage, with a live soundrack by William Fowler Collins, whose work has been described as a cinematic fusion of dark ambient, noise and black metal. Collins records for the Type record label and has additional releases on Root Strata and Digitalis. His 2009 release, ‘Perdition Hill Radio’ received international critical acclaim and was listed by Boomkat as one of the top 100 albums of 2009.

Pieter Geenen

“In resistance to a demystification of things and as an anti-image of traditional media Pieter Geenen explores the subtle, hidden and ‘slow’ characteristics of things. The audience needs to complete the blurred ‘gestalt’, decode the spatial ambiguities, assume presences and see trough all omissions and shortenings. Between the hasty atmospherical, though everlasting, almost frozen cinematic moment rules a strong individual sense of space and time. Geenen explores the vague boundaries of the visible and the audible (and how they relate to each other), and moves on the thin line between the moving and the static image. Listening and watching becomes intense, intimate, alienating, contemplating and almost tangible in the context of an undisturbed stillness.”

Phantom Limb & Earth’s Hypnagogia

Phantom Limb & Earth’s Hypnagogia is the project of Jaime Fennelly (of Peeesseye, Evolving Ear Records) and Shawn Hansen (who also has releases on Evolving Ear). The two join their forces here for an epic ride through the volatile moments of twilight. A synaesthetic kind of excursion, inspired by the deepening shades of light and dramatically rendered through the warm, swelling tones of Farfisa organ and analog synthesizer. ‘In celebration of knowing all the blues of the evening’ in all its moody and cinematic drive could be the quintessential ‘soundtrack for an imaginary film’… Together with visual artist Nate Miner they have been working for years at a movie project of the same title.

Disinformation

Disinformation (aka Joe Banks) is a research, installation and sound art project, active since 1995, which pioneered the use of electromagnetic (radio) noise from live mains electricity, lightning, laboratory equipment, trains, industrial and IT hardware, magnetic storms and the sun etc, as the raw material of musical and fine-art publications, exhibits and events. Sci-Fi author Jeff Noon wrote in The Independent that “people are fascinated by this work”, and The Guardian commented “Disinformation combine scientific nous with poetic lyricism to create some of the most beautiful installations around”. At show is ‘The Origin of Painting’ – ” electromagnetic sound and shadow wall, autodestructive portraiture and experimental painting installation”.

+ film- and videoworks by Deborah Stratman, Jeanne Liotta, and others

Surface Tension (Friday March 19th)

Paul Abbott, Seymour Wright & Ross Lambert

One of our recent discoveries is the work of musician and video artist Paul Abbott. His videos are fascinating conundrums of language, image and sound, disquieting disjunctive structures whose covert syntax refuses to be unpicked. Abbott is also one of the participants in Eddie Prévost’s weekly improvisation workshop in London, now in place for almost a decade and with a remarkable 250-plus musicians on its past and present roll. Upon our instigation, Abbott will set up a dialogue between visual and auditive elements, in interaction with saxophonist Seymour Wright and guitarist Ross Lambert – two key players in the London improvising scene. Seymour has described his playing as “enquiry into saxophonic actuality, through the potential inherent in, for instance, imagination, re-proportion, inversion, transformation, juxtaposition, construction, deconstruction, reconstruction, permutation, truncation and extension”. Lambert has been described (by Brian Morton) as “that rare individual these days, a jazz musician who doesn’t necessarily have any formal founding in the tradition. He admits to listening only to important records and then rarely, and considers a focus on the politics and practice of experimental music more important than documenting his work. If all this, and the fact that he plays guitar, which has often been a fifth column instrument in jazz, smuggling in energies from other forms, suggests a man who has declared his own Year Zero and separated himself from any existing performance practice, the impression is faulty and incomplete. Whatever its source, Lambert’s music belongs in a long community of practice on this hearing”.

Karen Mirza, Brad Butler & David Cunningham

Karen Mirza and Brad Butler make film and video installations that question the filmic, sculptural and architectonic qualities of the moving image. Mirza / Butler install their films in architectural configurations, frequently presenting them across two or three screens, the questions of past and presence, framing and projection are interrogated and expanded notions of these are proposed. Their work aims to blur the distinction between film and sculpture, art and cinema. For their piece ‘The Space Between’ they collaborated with musician and installation artist David Cunningham, who has worked with an eclectic range of people, such as David Toop, Michael Nyman, Martin Creed, Cerith Wyn Evans, and Sam Taylor-Wood. Cunningham’s soundtrack mirrors the open structure of the film with looped, repeated and pulsed sound.

Dominique Petitgand

Dominique Petitgand’s works are arrangements of sound elements that connect with and strain against each other. They place listening at the centre of the creation process of meaning. “For me, the search for form takes place at the level of perception, at the level of what is going on inside the head of the listener”, Petitgand remarks. “I don’t have the impression of creating an object; rather, I set in motion mental perceptions, acts of reflection, of thinking, memory and imagination. My work is closer to the phenomenon than the object”. Silences seen as spaces of montage, the combination of various temporalities and numerous narratives in a single work and the spatialisation of time also emphasise the listening experience. “I like the idea that you can play with listening the way you can play with looking”.

Lis Rhodes

While firmly rooted in the history of experimental film, Lis Rhodes’ films cross into performance, photography, writing, and political analysis. Her expanded cinema piece ‘Light Music’ (1975-77) is one of the results of her investigation into the relationship between shapes and rhythms of lines and their tonality when printed as sound. “The film is not complete as a totality; it could well be different and still achieve its purpose of exploring the possibilities of optical sound. It is as much about sound as it is about image; their relationship is necessarily dependent as the optical soundtrack ‘makes’ the music, It is the machinery itself which imposes this relationship. The image throughout is composed of straight lines. It need not have been.”

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

ARTISTS IN FOCUS

Morgan Fisher (Saturday March 20th)

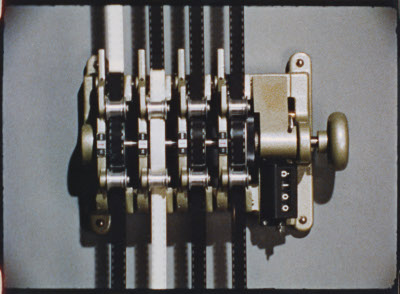

Fisher’s films are an exploration of the film apparatus and its physical material, as well as of moviemaking production methods : from film’s standard gauge (35mm) to the use of production stills, the narrative role of inserts and the invisible importance of the projectionist. Fisher plays with the concepts of film, cinema and filmmaking, creating a unique and intimate view of cinema and its physical representation. ” One thing my films tend to do is examine a property or quality of a film in a radical way,” he says. “Being radical is a modest form of being extreme. They each examine an axiom of cinema and say, ‘What if ?'”

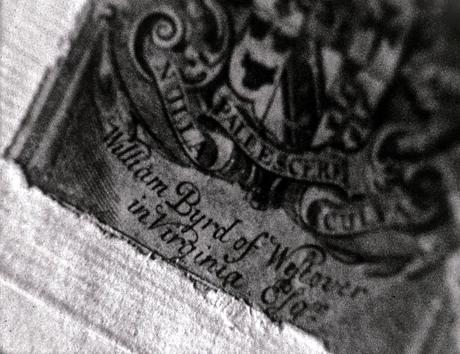

David Gatten (Sunday March 21st)

Over the last ten years Gatten’s films have explored the intersection of the printed word and the moving image, while investigating the shifting vocabularies of experience and representation within intimate spaces and historical documents. Through traditional research methods (reading old books) and non-traditional film processes (boiling old books), the films trace the contours of both private lives and public histories, combining elements of philosophy, biography and poetry with experiments in cinematic forms and narrative structures.

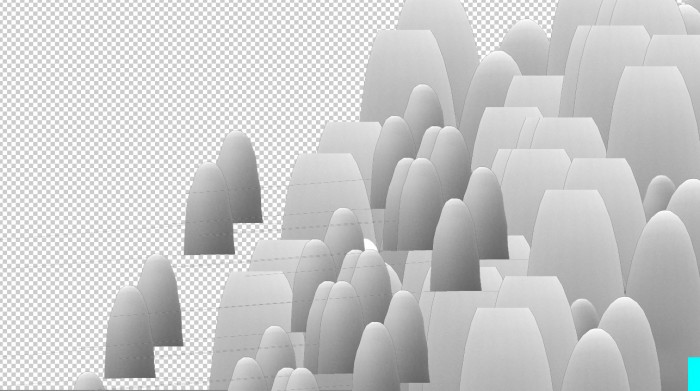

David O’Reilly (Wednesday March 17th)

Tags: “animation, computers, internet, 3d, cats, chronic depression, stories, independent film-making, more cats, trauma, low-art, Berlin, talking animals, theory, dreams, drama, compression, nonsense, rendering, artificiality, aesthetics, suicide, symbolic representation, narrative, experimental, cats, paper, computer, software, bsod, error, mspaint, lofi, sss, author, auteur, pop culture, fine art, narcissism, pretentiousness, dramaturgy, love, hallucination, jpeg, mov, mpeg, Ireland, Kilkenny, 1985, serial gen, crack, torrents, cinema, anarchy, color-space, z-space, real time, anti-aliasing, aliasing, xxx, walt disney, simulation, distractions, internet etc.”

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

SCREENINGS

Vital Signs

Apart from the selection of recent works (see this blog for regular updates), we will present the video and film programme ‘Vital Signs’, which will focus on the the formation of the meaningful, exploring the edges of meaning and the boundaries of communication. With works by Katarina Zdjelar, Imogen Stidworthy, Anri Sala, Gary Hill, John Smith, David Gatten, Guy Sherwin, Pavel Medvedev, Kathrin Resetarits, Peter Sulyi and many others.

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

EXHIBITION

‘Digest Sound’ investigates the sometimes successful, sometimes failing marriage between communication and technology, featuring work by Omer Fast, Matt O’Dell, Jean-Luc Moulène, Erik Bunger, Joe Banks & Barry Hale…

—————————————————————————————————————————————–

CONCERTS

Organised by Kraak. Some confirmed names:

Oneohtrix Point Never

The Wire wrote this about his record ‘Rift’: “A concept suite about astronauts lost in outer and inner space, Daniel Lopatin’s solo synth explorations were both full-on retro fetishism and a highly inventive reworking of futures past. With virtually no beats, just chorused, arpeggiated oscillators drifting freely through space, ‘Rifts’ chimed in with Noise’s current reflective phase, the new-New Age of The Skaters and Dolphins Into The Future, and the hazy 80s memories channelled by Hypnagogic pop. Lopatin has accomplished something many musicians making so-called experimental music fail to do: open our ears to new sonic possibilities and, more importantly, force us to reconsider and rewire some of our most basic assumptions.”

Carlos Giffoni

The Wire again: “In interviews, Brooklyn noise head Carlos Giffoni often talks about striving to avoid repetition. So far he’s kept his word: while his work has a clear consistency – no one could mistake it for anything but noise – each of his albums is distinct. 2005’s ‘Welcome Home’ contains super-detailed electronic pieces, while 2007’s ‘Arrogance’, made on analogue equipment, eschews miniaturism for widescreen sound. ‘Eternal Noise’ (2008) is another left turn, offering simple pieces that change gradually and sometimes inaudibly. As the title implies, Giffoni here views noise as a constant stream he can tap into without obstructing its elemental flow. He hasn’t crafted these tracks so much as channelled them, funnelling basic tones into lengthy sonic rivers.”

More to come!