ARTIST IN FOCUS: Robert Beavers

03.04.2011 – 09.04.2011, Courtisane Festival 2011 (Gent) & Cinematek (Brussels)

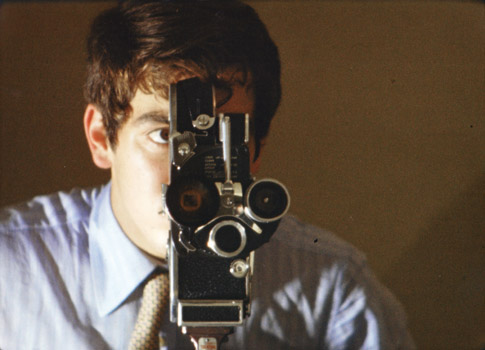

Robert Beavers (1949, Brookline, Massachusetts) is one of the most influential avant-garde filmmakers of the second half of the 20th century. Although born and raised in the United States, he has been living and making films in Europe since 1967. His 16mm films, at the same time lyrical and rigorous, sensuous and complex, are inhabited by the landscapes, the architecture and the cultural traditions of the Mediterranean and Alpine cities and countryside where they are filmed, and yet reveal deeper personal and aesthetic themes. As he acknowledges himself, he strives “for the projected film image to have the same force of awakening sight as any other great image.” He regards filming as part of a complex procedure, which begins in the eyes of the filmmaker and is shaped by his gestures in relation to the camera. Beavers’s attention to the physicality of the film medium is evident also in the editing, a fully manual process that leads to a unique form of phrasing. Harry Tomicek calls it a form of “cinematic breathing”: “an exchange of speech and silence, emergence and concealment. Robert Beavers might be the only filmmaker in the world whose works announce the mystery of this process.”

Until the late 1990s his films were very rarely shown, but recent retrospectives at the Tate Modern London, the Whitney Museum in New York, Berkeley Art Museum & Pacific Film Archive in Berkeley and the Austrian Film Museum in Vienna have finally brought to his work the attention it deserves. Courtisane and Cinematek will join forces to present his oeuvre in Ghent and Brussels, a city Beavers has a strong attachment to but where his work hasn’t been screened in several decades. Brussels was not only the first European city where he settled together with his partner filmmaker Gregory Markopoulos (1928-1992) after leaving the United States but also where his film culture and cinephilia developed, thanks to Jacques Ledoux, the then curator of the Royal Belgian Film Archive. Ledoux also encouraged Beavers to continue making films, and is one of the protagonists of Plan of Brussels (1968). From his Early Monthly Segments to his most recent work The Suppliant (2010), this selective retrospective in Brussels and Ghent covers more than 40 years of work and represents for Beavers an occasion to return to the scene of his beginnings as a filmmaker, the Brussels Cinémathèque.

On the last day of the Courtisane festival, April 3, Robert Beavers will present a selection of films of his own as well as by other filmmakers in Ghent. The following week, four more screening programmes will follow in Cinematek, the film theatre of the Belgian Royal Film Archive.

With the support of SWISS FILMS

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

PROGRAMME 1

Film-Plateau, Gent (Courtisane Festival)

Sun 03.04.2010, 15:00

Ruskin

1975/1997, 35mm, b/w & colour, sound, 45’

Filmed in Italy (Venice), Switzerland (the Grisons) and England (London).

“Ruskin visits the sites of (art critic) John Ruskin’s work: London, the Alps and, above all, Venice, where the camera’s attention to masonry and the interaction of architecture

and water mimics the author’s descriptive analysis of the ‘stones’ of the city. The sound of pages turning and the image of a book, Ruskin’s Unto This Last, forcibly reminds us that a poet’s perceptions and in this case his political economy, are preserved and reawakened through acts of reading and writing”. (P. Adams Sitney)

The Suppliant

2010, 16mm, colour, sound, 5’

Filmed in USA (New York)

”My filming for The Suppliant was done in February 2003, while a guest in the Brooklyn Heights apartment of Jacques Dehornois. When I recollect the impulse for this filming, I remember my desire to show a spiritual quality united to the sensual in my view of this small Greek statue. I chose to reveal the figure solely through its blue early morning highlights and in the orange sunlight of late afternoon. After filming the statue, I walked down to the East River and continued to film near the Manhattan Bridge and the electrical works; then I returned to the apartment and filmed a few other details. I set this film material aside, while continuing to film and edit Pitcher of Colored Light, later I took it up twice to edit but could not find my way. Most of the editing was

finally done in 2009 then I waited to see whether it was finished and found that it was not. In May 2010, I made several editing changes and created the sound track with thoughts of this friend’s recent death.” (RB)

Pitcher of Colored Light

2007, 16mm, colour, sound, 23’

Filmed in USA (Falmouth, Massachusetts)

“…The shadows play an essential part in the mixture of loneliness and peace that exists here. The seasons move from the garden into the house, projecting rich diagonals in the early morning or late afternoon. Each shadow is a subtle balance of stillness and movement; it shows the vital instability of space. Its special quality opens a passage to the subjective; a voice within the film speaks to memory. The walls are screens through which I pass to the inhabited privacy. We experience a place through the perspective of where we come from and hear another’s voice through our own acoustic. The sense of place is never separate from the moment.” (RB)

CARTE BLANCHE TO ROBERT BEAVERS

Marie Menken

Bagatelle for Willard Maas

US, 1958/1961, 16mm, colour, silent, 5’30”

Ute Aurand

India

DE, 2005, 16mm, colour, sound, 57’

“The first time that I viewed a film program by Marie Menken, I dismissed it; the same happened with my first viewing of a film by Ute Aurand. These filmmakers were opposite poles to my own way of filmmaking, and, in selecting this carte-blanche program, I reflect how my experience of their films has changed. Fortunately I had other occasions to see their films. The initial irritation and uncertainty suddenly opened to recognition. To experience discontent can be a sign of growth, a turning point in (my) appreciation of a film, a piece of music or a poem. Filmmakers, like Menken or Aurand, hide themselves in their directness and simplicity. Their use of handheld camera and their awareness of rhythm create a vision that draws its strength from their surroundings, but the vitality of this open embrace contains a genuine shyness or reticence. It was not until I recognized this that I could see how their lyric contains a depth.

Marie Menken’s Bagatelle for Willard Maas is a clear example. It possesses the qualities of angularity, rhythmic emphasis, sensitivity to surfaces and other means to express sensuousness, and through her spontaneity, she carries her film from one mood to the next until we reach the conclusion. And she is a collaborator; she allows Teiji Ito’s music an equal place. The film appears to meander, the way that a visitor to Versailles might, but I believe that in the change in moods there are elements of a story, one is the encounter of a gentle sphinx with a wounded slave and the other is the revolution.

Using a different metaphor to introduce Ute Aurand’s India, I could say that it is a ‘symphony’, and that her three visits to Pune are its three movements. The basic rhythm is established through her filming short clusters of images, often with camera movements that are like “little side steps,” and sometimes these clusters develop into complex rhythmic variations on the sights that she discovers as she walks, rides or drives through the city. This kaleidoscope of impressions, both of sound and image, is punctuated by pauses in which the filmmaker inserts her own presence through details of a shirt, a coffee cup, a notebook, an earring or other self-reflections in her room.

Some images have an animistic power; I remember a cluster of three small leaves at the base of a giant tree. They shiver in the wind to the sound of drums and that precedes a truly ecstatic dance-procession, one of an entire series of dances in the film.

Aurand also has the courage to approach children’s faces. She has said, “Even though I am living through what I see, what I want to reach is the invisible. The screen is a doorway; it is like my relation to the children, also a vehicle to the beyond.”

Returning once more to her camera’s “side steps”, I have only recently noticed how these movements allow her a beautiful ease and swiftness in transitions. These transitions from one subject to the next are also like music, but a music that incorporates qualities that are less dualistic than our own.

We see in these films two filmmakers using the very common opportunity of filming their travel; one is a ‘tourist’ visiting Versailles, the other is in India. But for the spectator who will look carefully, there is a generosity and probity that reaches through the surface pleasure to the embrace of life and mortality.” (RB)

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

PROGRAMME 2

Cinematek, Brussels

Tue 05.04.2011 19:00 (in the presence of Robert Beavers)

Early Monthly Segments

1968-70/2002, 35mm, colour, silent, 33’

Cast: Robert Beavers, Gregory Markopoulos, Tom Chomont.

Filmed in Switzerland, Germany (Berlin), and Greece.

“Early Monthly Segments, filmed when Beavers was 18 and 19 years old, now forms the opening to his film cycle, “My Hand Outstretched to the Winged Distance and Sightless Measure.” It is a highly stylized work of self-portraiture, depicting filmmaker and companion Gregory J. Markopoulos in their Swiss apartment. The film functions as a diary, capturing aspects of home life with precise attention to detail, documenting the familiar with great love and transforming objects and ordinary personal effects into a highly charged work of homoeroticism”. (Susan Oxtoby)

Work done

1972/1999, 35mm, colour, sound, 22’

Filmed in Italy (Florence) and Switzerland (the Grisons).

”Bracing in its simplicity, Work done was shot in Florence and the Alps, and celebrates an archaic Europe. Contemplating a stone vault cooled by blocks of ice or hand stitching of a massive tome or the frying of a local delicacy, Beavers considers human activities without dwelling on human protagonists. Like many of Beavers’ films, Work done is based on a series of textural transformative equivalences: the workshop and the field, the book and the forest, the mound of cobblestones and a distant mountain”. (J. Hoberman)

AMOR

1980, 35mm, colour, sound, 15’

Cast: Robert Beavers.

Filmed in Italy (Rome, Verona) and Austria (Salzburg).

“AMOR is an exquisite lyric, shot in Rome and at the natural theatre of Salzburg. The recurring sounds of cutting cloth, hands clapping, hammering, and tapping underline the associations of the montage of short camera movements, which bring together the making of a suit, the restoration of a building, and details of a figure, presumably Beavers himself, standing in the natural theatre in a new suit, making a series of hand movements and gestures. A handsomely designed Italian banknote suggests the aesthetic economy of the film: the tailoring, trimming, and chiseling point to the editing of the film itself.” (P. Adams Sitney).

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

PROGRAMME 3

Cinematek, Brussels

Thu 07.04.2011 18:00

Winged Dialogue

1967/2000, 16mm, colour, sound, 3’

Cast: Gregory Markopoulos, Robert Beavers.

Filmed in Greece (Island of Hydra)

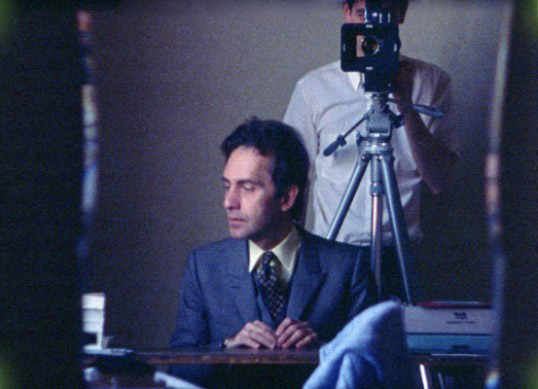

Plan of Brussels

1968/2000, 16mm, colour, sound, 18’

Cast: Robert Beavers, Giséle Frumkin, René Micha, Jacques Ledoux, Pierre Apraxine, Dimitri Balachoff and others.

Text: “Duvelor” by Michel de Ghelderode.

Filmed in Belgium (Brussels).

Note: The final edit combines both films on a single reel.

“Winged Dialogue details with growing clarity the desperate beauty and sexuality of the body animated by it’s soul, essence blindly reaching out, touching, in brilliant patterns through and beyond those of the vanishing images, expressed vividly in the after-image on the mind, on the soul’s eye”. (Tom Chomont).

“Shedding all traces of narrative in Plan of Brussels, Beavers filmed himself in a hotel room, both at his work desk and lying naked on the bed, while in rapid rhythmic cutting, and sometime in superimposition, the phantasmagoria of people he met in Brussels and images from the streets flood his mind”. (P. Adams Sitney).

From the Notebook of …

1971/1998, 35mm, colour, sound, 48’

Cast: Robert Beavers, Gregory Markopoulos and others.

Filmed in Italy (Florence).

“From the Notebook of … was shot in Florence and takes as its point of departure Leonardo da Vinci’s notebooks and Paul Valéry’s essay on da Vinci’s process. These two elements suggest an implicit comparison between the treatment of space in Renaissance art and the moving image. The film marks a critical development in the artist’s work in that he repeatedly employs a series of rapid pans and upward tilts along the city’s buildings or facades, often integrating glimpses of his own face. As Beavers notes in his writing on the film, the camera movements are tied to the filmmakers’ presence and suggests his investigative gaze”. (Henriette Huldisch)

The Painting

1972/1999, 16mm, colour, sound, 13’

Cast: Robert Beavers, Gregory Markopoulos.

Filmed in Switzerland (Berne) and USA (Boston).

“The Painting intercuts shots of traffic navigating the old-world remnants of downtown Bern, Switzerland, with details from a 15th-century altarpiece, “The Martyrdom of St. Hippolytus”. The painting shows the calm, near-naked saint in a peaceful landscape, a frozen moment before four horses tear his body to pieces while an audience of soigné nobles look on; in the movie’s revised version, Beavers gives it a comparably rarefied psychodramatic jolt, juxtaposing shots of Gregory Markopoulos, bisected by shafts of light, with a torn photo of himself and the recurring image of a shattered windowpane”. (J. Hoberman)

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Programma 4

Cinematek, Brussels

Fri 08.04.2011 20:00

Wingseed

1985, 35mm, colour, sound, 15’

Cast: Arno Gutleb. Filmed in Greece (Anavvysos, Lyssaraia).

“A seed that floats in the air, a whirligig, a love charm. This magnificent landscape, both hot and dry, is far from sterile; rather, the heat and dryness produce a distinct type of life, seen in the perfect forms of the wild grass and seed pods, the herds of goats as well as in the naked figure. The torso, in itself, and more, the image which it creates in this light. The sounds of the shepherd’s signals and the flute’s phrase are heard. And the goats’ bells. Imagine the bell’s clapper moving from side to side with the goat’s movements like the quick side-to-side camera movements, which increase in pace and reach a vibrant ostinato”. (RB).

Sotiros

1976-78/1996, 35mm, colour, sound, 25’

Cast: Robert Beavers, Gregory Markopoulos.

Filmed in Greece (Athens, Sparta, Leonidion), Austria (Graz, Rein) and Switzerland (Berne).

Note: Three films are now combined within a single work.

“In Sotiros, there is an unspoken dialogue and a seen dialogue, The first is held between the intertitles and the images; the second is moved by the tripod and by the emotions of the filmmaker. Both dialogues are interwoven with the sunlight;s movement as it circles the room, touching each wall and corner, detached and intimate”. (RB).

Efpsychi

1983/1996, 35mm, colour, sound, 20’

Cast: Vassili Tsindoukidis.

Filmed in Greece (Athens).

“The details of the young actor’s face – his eyes, eyebrows, earlobe, chin, etc. – are set opposite the old buildings in the market quarter of Athens, where every street is named after a classic ancient Greek playwright. In this setting of intense stillness, sometimes interrupted by sudden sounds and movements in the streets, he speaks a single word, “teleftea”, meaning the last (one), and as he repeats this word, it moves differently each time across his face and gains another sense from one scene to the next, suggesting the uncanny proximity of eroticism, the sacred and chance”. (RB).

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Programma 5

Cinematek, Brussels

Sat 09.04.2011 18:00

The Hedge Theatre

1986-90/2002, 35mm, colour, sound, 19’

Cast: Robert Beavers, Gregory Markopoulos.

Filmed in Italy (Rome, Brescia).

“Some years after filming AMOR, I returned to Italy and found the source for a new film in the architecture of Borromini and in a grove of trees with empty birdcages. (A grove of trees, a rocolo, in which hunters would set out cages with decoys, called richiami, whose song attracted other birds.) The buoyant spaces of these cupolas, the sewing of a buttonhole, and the invisible bird hunt are all elements in the sustained dialogue of The Hedge Theatre”. (RB).

The Stoas

1991-97, 35mm, colour, sound, 22’

Cast: Robert Beavers.

Filmed in Greece (Athens, Gortynia).

“The title refers to the colonnades that led to the shady groves of the ancient Lyceum, here remembered in shots of industrial arcades, bathed in golden morning light, as quietly empty of human figures as Atget’s survey photos. The rest of the film presents luscious shots of a wooded stream and hazy glen, portrayed with the careful composition on 19th century landscape painting. An ineffable, unnameable immanence flows through the images of The Stoas, a kind of presence of the human soul expressed through the sympathetic absence of the human figure”. (Ed Halter).

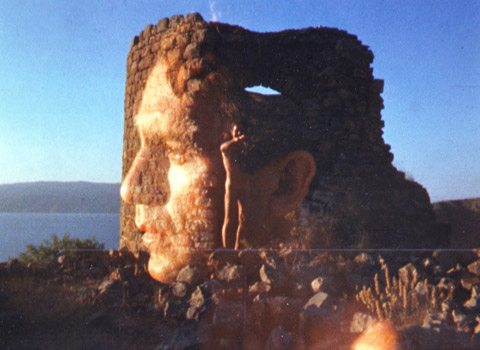

The Ground

1993-2001, 35mm, colour, sound, 20’

Cast: Robert Beavers. Filmed in Greece (Island of Hydra).

“What lives in the space between the stones, in the space cupped between my hand and my chest? Filmmaker/stonemason. A tower or ruin of rememberance. With each swing of the hammer I cut into the image and the sound rises from the chisel. A rhythm, marked by repetition and animated by variation; strokes of hammer and fist, resounding in dialogue. In this space which the film creates, emptiness gains a conour strong enough for the spectator to see more than the image – a space permitting vision in addition to sight”. (RB).

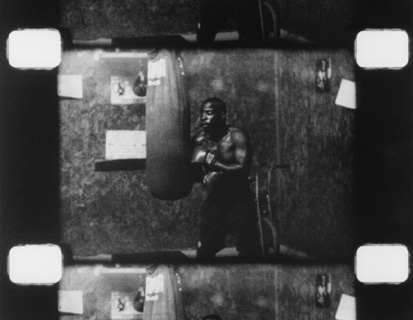

Meditations on Revolution (1997- 2003) is the title of a series of films that represent the heart of Fenz’s oeuvre. “Revolution” does not refer here to the overthrow of a form of state, but to the countless nameless revolutions inscribed in rural and urban spaces, steeped in hollowed and smiling faces, dancing on the rhythms of a world in constant transition. “Revolution” takes here the form of a sensible world. A dance lesson in the bustling streets of Havana, children playing in a shanty town in Rio de Janeiro, the hard-trained torso of a boxer in Greenville, Mississippi, the proud but fatigued monologue of a jazz musician (the late Marion Brown) in New York: the politics of Fenz’s films does not lie in lecturing on economical or geo-political issues, but in the reframing of bodies, the world they live in and the place that they take in that world. Politics resides in the confrontation of power and impotence, reality and possibility, inside and outside, “here” and “there”. It lies in the way films are made. “Say how things are real”, as Godard proclaims, is what making political films implies. Making films politically: “to say how things really are”.

Meditations on Revolution (1997- 2003) is the title of a series of films that represent the heart of Fenz’s oeuvre. “Revolution” does not refer here to the overthrow of a form of state, but to the countless nameless revolutions inscribed in rural and urban spaces, steeped in hollowed and smiling faces, dancing on the rhythms of a world in constant transition. “Revolution” takes here the form of a sensible world. A dance lesson in the bustling streets of Havana, children playing in a shanty town in Rio de Janeiro, the hard-trained torso of a boxer in Greenville, Mississippi, the proud but fatigued monologue of a jazz musician (the late Marion Brown) in New York: the politics of Fenz’s films does not lie in lecturing on economical or geo-political issues, but in the reframing of bodies, the world they live in and the place that they take in that world. Politics resides in the confrontation of power and impotence, reality and possibility, inside and outside, “here” and “there”. It lies in the way films are made. “Say how things are real”, as Godard proclaims, is what making political films implies. Making films politically: “to say how things really are”.