By Thierry Lounas

Interview with Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub, conducted on 6 July 1999, with the participation of Pedro Costa. Originally published as ‘La sorcière et le rémouleur’ in Cahiers du cinéma no. 538 (Septembre 1999). Translated by Ted Fendt and Stoffel Debuysere

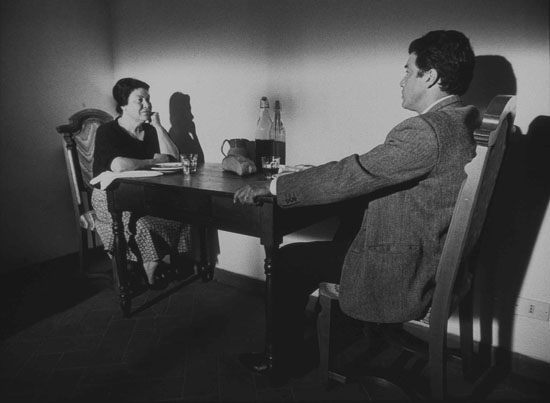

Whether or not by chance, the road that led to Rome passed through a small town in Tuscany called Pontedera, where recently was held a retrospective of the films of Pedro Costa, a great admirer of the Straubs. Chance in any case that the director of the event, Marco Abondenza, made us discover the village of Buti, which is atypical and artistically committed. A man, whose son played in Dalla nube alla resistenza twenty years ago, mentioned that the village theater would show the next Passion of Christ, adapted from Pasolini, in Cape Verde. He also remembered the presence of Godard at one of the presentations of Sicilia ! that the Straubs had organised in preparation of their film. He then invited us to see the Landi house where the Straubs lived during the rehearsals and where the central scene in Sicilia ! had been shot. In front of the fireplace, a discussion unravelled with Marcello Landi and his wife. Once arrived in Rome, still in the company of Pedro Costa, we had a little taste of the Italian mythology surrounding the Straubs. Some not without contempt, others with tenderness, gave them the nickname “punkabbestia”, which usually refers to the hordes of vagrants roaming the streets of Rome, flanked by their dogs. They are not vicious, they say, just a little cumbersome. Indeed, the Straubs may be punkabbestia, punk filmmakers with a love for animals, and capable of violent assaults themselves. We then headed to Borgata Petrelli, on the outskirts of Rome, where the Straubs live. It is there that this interview took place, in all tranquillity, in the presence of a score by Bach and a painting by Cézanne. During this time, a large fire was burning not far away, which, having attracted the televison cameras, inspired Jean-Marie Straub to remark: “What they’re ignoring is that nothing is more difficult than filming a fire.”

Sicilia ! is about the same length as Du jour au lendemain (1997), one hour and five minutes to be precise. For Du jour au lendemain the score and the libretto imposed the duration. For Sicilia !, there was a much vaster work, Conversazione in Sicilia by Elio Vittorini, that you have only used part of. How did you adapt the novel?

JMS: We have left more than half of the novel aside, mainly things that could have yielded a Visconti or Fellini film, especially the last part which is completely metaphorical. But it’s already been thirty years since I’m completely wary of metaphors, even before I got to know kafka’s expression: “Metaphors are one among many things which make me despair of writing.” Films can’t be made with metaphors. To allude to the final part of the novel: it is not possible, in cinema, to film people who are dying, in the dark, of typhus or other things. Even John Ford would not have allowed it.

More than choosing passages that interested you, I suppose you needed to rework what you kept.

JMS: In this novel there is not a single line of dialogue that is complete. Everything is interspersed with psychological or descriptive reflections. Additionally, there is an entire part of the text written in indirect style. But it’s not the first time this has happened to us. The long text dealing with the death of Thérésa in the Kafka film (Amerika/Class relations) was also in indirect style. Here, the text of the Great Lombard, who is sitting in the train and who we see getting up to violently close the compartment door before taking his seat to talk about the stench of the two cops, does not exist. In the novel, more than sixty percent of it is written in indirect style. About Not Reconciled (1965), I said it was a film that was lacking something. The same goes for Sicilia !, but in different way. One should never overdo it on the pretext of having a two-hour film. There is a scene in Mon Oncle that I must have mentioned already twenty times, in which a man who is missing an eye is painting white lines on the tarmac. Suddenly he sees a crushed-raspberry, olive-green Buick pull up, with a playboy and a beautiful girl inside. He follows it with his eye, then raises his brush and says? “Do you want another coat?” Cinema is the opposite. Otherwise it’s Tchaikovsky: there is nothing breathing, everything is crammed in, sealed off. It’s exactly what Brecht has Tiresias say in Antigone: “Und mehr braucht mehr, und wird am End zu nichts”, more needs more, and in the end becomes nothing. Aesthetics is the opposite. One must dilate as much as possible, leaving enormous spaces and then make extreme constrictions. That’s the whole difference between Tchaikovsky and Bach, Beethoven, Schönberg or Webern, who leave in silences. That is aesthetic responsability: take a maximum risk with maximum caution.

What do you mean by caution?

JMS: Knowing how far we can go too far.

And how far can we go too far?

DH: We decide on the basis of the material. With fear and trembling. If you decide to leave in a silent shot, you know it is not without risk.

(Pedro Costa) Are you sometimes afraid to film?

JMS: No. It has nothing to do with Kierkegaard’s Fear and Trembling. It is a matter of love and respect. We say to ourselves that what we film is something that will no longer exist afterwards, because it will already be different, and we won’t film it again. So in that sense, yes, we are a little afraid. But in this sense only.

DH: You’ve seen Della nuba alla resistenza. You remember this shot with the oxen cart, after the dialogues. While editing, we did not know if we were going to keep it or not. Finally, we chose to keep it in, knowing very well that in doing so we were taking a huge risk. We know very well that some viewers will leave. But we also know that perhaps one day, as it happened with the car rides in History Lesson, one will see that it is at least as strong as the dialogues.

How does this thing that you finally decide to keep become necessary?

DH: What bothers or moves people is feeling that it is necessary without knowing why.

JMS: I come back to Vittorini: thanks to a story like his, of which we have left out half, there is the possibility of having a film of which the fiction is very strong without the film being loaded with fiction. Because we do the opposite of what producers do when they buy the rights of a book. They don’t buy the texts, they buy a plot. And from there, they clog the holes. Here, the intrigue is there, if we speak of intrigue in the Cornelian sense, but it does not devour the material of the film. It is not in the foreground, it is cited, suggested. In that sense, it is completely different than Du jour au lendemain, which is theatre.

DH: An intrigue that is there without devouring the rest: that is also true of a film like Jean Renoir’s La nuit du Carrefour. If the film is impressive and we’re not completely dissapointed at the end – as is almost always the case with police films – it’s precisely because it’s not wrapped up.

In regards to the “story”, Sicilia ! is much closer to Not reconciled, with its different layers of time and history.

JMS: I’ll leave you the responsibility of this parallel. In 1965 I said, about Not reconciled, that I had risked making a film that was lacking something. But there is not only Not reconciled. Without looking to make comparisons, there is a film which is very related to Sicilia !, that it picks up from all while trying to do something else: Class relations. There is this similar desire to refuse to make a historical film which is dated in the images. Moreover, Sicilia ! and Class relations have another point in common. Class relationships was meant to be a twenty minutes film based on Kafka’s The Stoker, and Sicilia ! was initially meant to be composed only of the sequence with the orange vender, which correponds to a personal experience. During our first trip to Sicily in 1971 or 1972, at the time of Moses and Aaron, while driving around with the 2CV of Danièle’s mother, we discovered, near a river, mountains of oranges that had been thrown away to prevent the prices to fall. It is also the story that you hear at the beginning of Brecht’s Kuhle Wampe, with which Sicilia ! also has something in common, without it being premeditated by us. The other title of Kuhle Wampe is “To Whom Does the World Belong?”. And we amused ourselves, after the fact, by giving Sicilia ! the subtitle male offendere troppo il mondo (too evil to offend the world)

Sicilia ! seems to me more ample, more vast in what it evokes than Du jour au lendemain. We could say it’s more generous.

DH: This is mainly because Du jour au lendemain takes place in only one space. It’s like something set on a bus: it’s always heavier.

JMS: In Sicilia ! there is a completely different social reality. Du jour au lendemain stages a petit-bourgeois family constructed from two cultural machines, the male singer and the female singer. In Sicilia !, it is no longer an affair of cultural machines. The actors had never set a foot on a theater stage, and most of them didn’t know what grammar was. And their jobs were also different: there were several plasterers, a tiler, a seller of neckties. The mother had a life that was very similar to the one in the film. When you see what these people have managed to do in Sicilia !, one understands how shameful the controversy in Cannes about non-professional actors was. The Italian newspapers have not stopped talking about it. There is one thing I discovered during the Cannes festival: the Italian press is just a notch below the press of Dr. Goebbels and Goering. And this happened in only four years time. You could read things like: “What’s with these films that have received awards and feature non-professional actors who in any case are bad and won’t make any career in cinema?” I read this in good democratic, liberal and bourgeois newspapers, which are nevertheless no flesh-peddler magazines.

DH: Bresson worked in this way his whole life. He never called on professional actors. Dreyer, despite everything, took on actors. Obviously, at the time there were fewer Le Pen-like arguments such as “They won’t make a career, they received an award, it’s a shame.”

JMS: This goes way back. Do you know why all Italian films are dubbed? It comes from a law Mussolini made to protect the Italian language. That’s where the parasitism of dubbing started. And when they dubbed Renoir’s Toni a few years ago, the Italian actors arriving in the south of France, Toni in particular, were dubbed by Milanese voice-actors imitating the Sicilian accent, so they wouldn’t be confused with the other actors dubbed in Italian. All of the sudden, the Italians who landed in the south of France became Sicilians arriving in the north of Italy. That is what they are capable of in Italy … Andreotti, as leader of the Christian Democracy, once wrote a letter to Filmcritica, at the time when it was still a small magazine, to explain that one had no right to make films like the Bicycle Thief, that dirty laundry shouldn’t be aired in public.

Are there for you advantages in shooting with non-professional actors, rather than with professional ones?

JMS: Renoir said that he could have made a broom act.

DH: Undoubtedly there is less need to play tricks with non-professional actors.

JMS: It’s true, but we did have some difficulties with the mother in Sicilia !, with whom we started working three months before the others.

DH: Because she played tricks on us.

JMS: When Danièle brought up the text I wrote, based on Conversations in Sicilia, in 1992, and proposed to make it into a film, I answered yes, on the condition that we would rework it using the same method we used for Antigone (1992), meaning that we would have to recruit actors on the spot. The theatre of Buti had written to us ten years before, saying that they would be delighted if one day we could make something with them. So I proposed the Vittorini to them, explaining that it would allow us to prepare actors of Sicilian origin in view of a film we wanted to make. They accepted right away, very kindly.

To continue to compare your two last films, in Du jour au lendemain there is a kind of dispute, a violent reaction of the woman against the confusion that has befallen her husband. She ends up using the same spectacular means as her adversery, in order to win back her husband. We could say that this reconquest is a war machine. In Sicilia !, it is no longer necessary, as the Great Lombard says, to be content with being good citizens, one has to find new responsibilities in order to be at peace with men. So it isn’t irrelevant that, in Du jour au lendemain, love inscribes itself in the interior of the couple and the discourse while in Sicilia ! it was born from an extramarital affair, from a subversion.

JMS: This women in Silicia !, i can tell you what she is: a witch. Him, the son, behaves like all men of the inquisition. Do you know how many witches the Inquistion burned? Thirty thousand. As many as Communards were executed. In Sicilia !, a gentle son cares for his old mother. Little by little, he starts to ask questions like an inquisitor. He judges her, then he realizes that as a woman she had her freedom and took it. A witch is revealed. That is what the Inquisition did not allow.

DH: It is at this moment that we understand why she gets angry when her son says to her “But did it not matter to you to no longer see the track, did it not matter to you to no longer hear the train” and she answers “But what does it matter…” You understand why. It is the fault of the railwaymen who let the police pass, it is the fault of this railroad that the strike was crushed.

JM: The woman in Du jour au lendemain is also a witch in her own way, because she takes on all the sorrow of the world in her machination. But she is a petit-bourgeoise who plays the witch, whereas the other, one fine day, is struck by lightning, by the arrival of this man. This wife of a railroad man suddenly reveals herself as a witch. It’s something completely different.

Sicilia ! is more vague than your other films, as if in the end there has to remain some uncertainty regarding the morality, the struggle, the couple. It’s a matter of movements and surges of politics and love that overtake whatever we might say about them, and that, in the final analysis, constitute a risk of which one doesn’t know, to come back to something you said earlier, if it is supported by a strong caution. One has the feeling that the film is extremely open and that a certain truth, whatever it is, is hard to formulate and can only be formulated at the price of multiple contradictions, the way in which the mother says of her father: “He had a head for a thousand things.”

JMS: If Sicilia ! seems more open than Du jour au lendemain, if it actually is, it’s because it’s a film in which there are many blanks. And to make a film of more than an hour is a luxury. I will tell you where all of this comes from. It’s what I call the science-fiction effect. Again there can be found some relation with Not reconciled: when, after the revelations about the hardship that the young Schrella has endured from eighty percent of her classmates, he finds himself on the bridge with Robert, who asks, looking for an explanation: “What are you? Are you Jewish?” At this moment in the film, there is no sign saying “1934, beginning of anti-semitism”. That is what I call the science-fiction effect. What is this strange world in which being Jewish could be an explanation? All of Sicilia ! is constructed in this way. For example, when we hear someone in the train saying “Ogni morto di fame è un uomo pericoloso” – each man dying of hunger is a dangerous man, this could have resulted in an entirely different film. We had foreseen to to do as in the Kafka film: to avoid, contrary to what Forman does in his Hollywood films, showing old cars that point out the periode we’re in. For Sicilia ! we went through a lot of trouble to find a train wagon that, without it being state-of-the-art, couldn’t be traced back to a certain period. We saw to it that the images weren’t historically dated, and the same for the costumes.

The black and white plays an ambiguous role in regards to this science-fiction effect.

JMS: The black and white is actually a correction of what I just described. There again we find the idea of caution. One has to go very far in making “modern” images but then it’s better to make them in black and white than in color. And when the Great Lombard, in the train, develops what I call his Communist utopia, it’s not the great European Communist utopia, as put forward by Hölderlin at the beginning of the last part of Empedocles. It’s not a universal Communist utopia, it is a Communist utopia that doesn’t state its name and is rather particular: it’s the Communist utopia of the men that have been massacred by Stalin in Ukraine. A Communist utopia that is searching for something, that dreams of something and that says: “To arrive at what I’m searching for, I would give everything I own, my land and my horse.” That goes very far. But if we point out that these words stem from after 1917, with in the background the war in Spain, and anticipating McCarthyism and everything else, it doesn’t work in the same way. That is what I call the science-fiction effect. Conversely, when we would have filmed the train in color, the film would have been too close to us.

DH: the silent moment, at the end of the train scene, ends up making our head spin. It becomes completely dreamlike. In color, the sky would have been blue…

JMS: Blue, not really, because it was grey… Even it there was the Sirocco blowing. But it’s true that with color the landscape wouldn’t have had this lunar quality. The black and white, in correcting the science-fiction effect, also allows to make things more abstract.

It’s not only the black and white or the lunar quality of the story that gives Sicilia ! its wide openness: there is also the undeceidability of place, a continuous movement that makes the film pass by without anything – the speech and the perception we have of the characters – ever concluding or freezing. Let’s take for example the scene between Silvestro and his mother, their movements, the fact that they occupy, in turn, the same place and that the space is very cut up. The geometry of the space keeps escaping us. The other day, seeing the house in Buti where this scene was shot, I was surprised by its smallness, while for Du jour au lendemain the space seemed more imaginable.

JMS: Let’s be more down to earth. Du jour au lendemain is simply a film with one single setting decor, and for the first time for us, a studio decor. It came from a challenge and the desire to amuse ourselves shooting between three walls, with one open wall and the orchestra in the back. Consequently, it’s a film that says what it is. Sicilia ! is a film starting in Messina, going up to the centre of Siciliy. That’s all.

Still, in Siclia ! we find ourselves, more than usual in your films, at odds with the space, with the off-space, especially in the train with the Great Lombard.

DH: When the Great Lombard is filmed alone in the train, it corresponds to a moment when he himself forgets the people around him. The risk is then knowing if you can succeed to get across the fact that, when he is shot alone in the train, he forgets what is around him. What remains of the off-space – and it’s something very strong that can’t be obtained in theatre – are his eyes looking through the window and in which you can see the light from outside.

JMS: But that should be any filmmaker’s strategy, small or great, young or old. It consists in playing with distance and space. We have gone through a lot of trouble with this compartiment. It was a matter of three centimeters to isolate it from the others. In reality we had to cheat a little. If we would have chosen a compartiment in second class, we wouldn’t have been able to do it. In first class, we won the fifteen centimeters that made the movement possible. At first, Willy Lubtchansky wanted us to take out a seat each time the camera changed places. I was against. So we filmed from each side of the seats, camera on the shoulder, except for the shot of the two cops, for which the camera was mounted on the level of the compartment door and turns towards the hallway.

DH: Jean-Marie was stubborn and he was right. Let’s say the material is much stronger because the train, Willy and the camera are moving at the same time.

JMS: As soon as we had chosen a lens, we couldn’t move an inch anymore. We didn’t have a zoom, and the lenses were fixed focal length. As soon as you choose a strategic position, you start doing things you had never done before. Thirty years ago, I would have been horrified to make a shot like the close-up of the great Lombard. The first time I used a 100mm lens was for The Death of Empedocles (1987). Before that I had only went up to 75. To return to the house, what made me decide to shoot this way was the black wall inside the fireplace. We lived in this house in Tuscany during the two months of rehearsals. We’d done quite a few explorations in Sicily, seen a lot of houses. Finally, we decided to shoot there. The wall in the fireplace is the only part of the house that is three centuries old. That was even worse than in the train. There are two camera positons in the whole sequence. There is one where you see him at the door and her at the fireplace, a position that is kept to film them both at the table and the window. The camera is close to the fireplace. And here it becomes exciting because all the shots are the result of a space that is not made of rubber. One feels very well that we haven’t tried to correct the perspective to make a more beautiful shot. You can play with the focal lengths but the perspective is correct, it’s always the same. It’s what we did with the Kafka, even if it was a bit more complicated then because we had to show solaridarity with Karl Rossman and, during the trial, be a bit closer to him than to the others. If you constantly change the perspective to make this or that shot, a close-up for example, then that close-up is of no importance at all.

In Class relations, we basically witnessed more of a trench war, camp against camp, exploiters against exploited. in Sicilia ! the dialectics, the conflict has given way to the evocation of memories and the world, even poetic and melancholic in the last sequence. It is about satisfaction, dignity, God …

JMS: This is a film of old people, that’s all, and it’s an airy film. This is a film in which there is air, in which the viewer or the citizen has more possibilities to exist, to breathe, than in the previous films … But there is not only the dignity of the grinder, the canons etc… It all the same ends with dynamite and that’s not nothing, especially if you think about certain recent events. And before the dynamite there is cannoni, cannoni and before that there is talk of sickles and hammers. And after the canons and the dynamite, there is another contradiction. When the grinder puts his hat back on and salutes, you have the impression that there are two characters who are saying goodbye to each other, each on one side of of an invisible abyss – they’re almost two Fordian characters. Then they begin to speak about healing and sickness. What is interesting is what is experienced at that moment. If you get to a point where humanity needs dynamite, it means that the world is sick. So there should be a convalescence. That, for me, is taken up by Beethoven… What the Great Lombard says is something typically Italian, which, twenty years ago, would have made me red with anger. But this time, I took it seriously. I said to myself “here is someone who is searching for something.” And as it was written in indirect style in the book, I put it in direct style, which made it more shocking and substantial. There is also the grinder who says “troppo male offendere il monde.” Reading this when I was eighteen, I would have shrugged my shoulders. But here, all of a sudden, it takes on a certain weight. It’s also in this sense that I say that this is a old people’s film. This is a film that could be called After the deluge.

There are other films that are set after the deluge and that, in the same way as Sicilia ! , advance following individual or collective memories, as well as their contradictions, defining some kind of space of the present by way of the past. I’m thinking of Hiroshima Mon Amour or other films by Resnais.

JMS: Let’s consider that as a compliment, and it sure is one. But let us rather talk of one of the people I like the most in contemporary cinema, Otar Iosseliani. I really loved Chasing Butterflies, but I think that his last film is a film armored by the story, the meaning, a desire not to leave holes or gaps. What can you do, cinema is not a language. Rivette and Moullet, a long time ago, reacted against the pornographic cinematographic writing. From my side, I arrived at the same conclusion. Cinema is not a language, in the way that Lenin said that bourgeois politics was pornography. Referential films, cinema becoming its own object, it’s dreadful.

Sicilia ! is much more beautiful and stronger for its dialogues being simple and yet dense. that’s what is undoubtedly at the origin of the impact and the surprise it produces. At once short and simple.

JMS: It’s very difficult to write texts like these ones. It’s what I told Otar when he asked me, ten years ago, “But why don’t you write your own texts?” I prefer to take them elsewhere because I know those texts will be richer than those I’m capable of writing, that they’ll resist me, and that I’ll have the courage to impose them on the actors for two, three, four months.

What is the meaning of the grinder’s enigmatic line: “one sometimes confuses the pettinesses of the world with the offenses to the world.”

JMS: Piccolezze, the small things of the world.

DH: Pettinesses! The grinder, who should have given this service for free, given the pleasure that he got from meeting Silvestro, apologizes for having tried to extort two francs more. He says to Sulvestro: “What kind of thing is that one, isn’t that a man who offends the world?” And the others says “Ooh” with a smile implying “Don’t exagerate, it’s all the same not serious.” The grinder answers him “Thanks you my friend, one sometimes confuses the pettinesses of the world with the offenses to the world.”

JMS: Moreover, I have to say that the word pettiness is well chosen, because in Italian it’s also a noun, even if it’s a bit forced. Probably, if we would have translated Piccolezze by small things, we would have translated inaccurately.

DH: No, that’s not true, it corresponds to narrow mindedness. Stop, in this domain you can’t beat me.

JMS: Ok… But I would like to add something about this thing (showing the press dossier) that I’m not unhappy about. There are three texts by Vittorini here. There is one very short one on Hölderlin, and another, even shorter, on color in cinema, and a final one, a bit longer, on Dreyer. I want it to be known that before making the film and even when we were editing it, I was completely unaware of these texts. One should give César his due: it was François Albéra who sent them to me. Why are they interesting? You see that Vittorini was interested in Hölderlin, which I would have never imagined. You also learn that he wrote about a film by Mamoulian: “Can color ever replace the innumerable shades of black and white?” It’s something important. In regards to the text on Days of Wrath, I’ve put it in there for one reason only: because of this witch. I also want it to be known that that I have never thought about Days of Wrath while working on Sicilia ! But I have to confess that when I arrived in Paris in 1954, the film that I knew the best, besides two films by Grémillon, two films and a half by Renoir en three films by Bresson, was Days of Wrath, which I must have seen at least seven times on 16mm, in my attic. So, consequentely, if there is something, in the scene between the mother and the son, that makes on think about Days of Wrath, it’s not surprising. A film that you see at that age leaves traces. In addition, I want Pagnol to be cited in regards to Sicilia ! I want that to the extent that I don’t really know Pagnol. But one day I discovered that images don’t exist for him. He does an enormous amount of work on the sound, and besides he bragged about it. Everyone was saying “You see, when the sound is right, the images are right”. But it’s not true. Pagnol locked himself in his sound-studio and, actually, he didn’t want to see anything. Of course, that’s not why the images don’t exist. But it happens that they don’t exist. One has to admit that, even is there is something in common between Toni and Pagnol, politically Renoir and him have nothing to do with each other. Pagnol is a bit tiresome. Bazin admired Manon des sources because of the priest’s long speech. I have never seen the film again. One would have to see if it stood the test of time. There are for example two filmmakers whom I admired a great deal when I was young and who irritate me today: Murnau and Rosselini. Their cinema ends up chasing its own tail.

You often talk about Dreyer, Bresson, Renoir, Ford, Stroheim, Lubitsch or Chaplin, but not a lot about filmmakers such as Hitchcock, Antonioni, Vertov or Ozu. Should we assume that you don’t have much sympathy for them?

JMS: It wasn’t Bresson who taught me about space, it was Hitchcock. When, in the course of a dialogue, there is a close-up and then a low-angle shot in close-up, it’s never fanciful. Even if I have slowly grown tired of Hitchcock’s stories and his roman-photo side. The first text I have written was sixty pages long and was about Antonioni’s Cronaca di un amore. It was about the film without really being about the film, based on Dostojevski’s The adolescent and Graham Greene’s The End of the Affair. I showed it to Bazin who told me that he wasn’t sure if the film would support this pyramid. For my part, I found it to be a synthetic and new cinema, particularly in regards to space. Bazin sent me to Marker, at Esprit, to try to publish the text. But nobody wanted to. After that, I went to Germany and I burned it. I also wrote a text about Rear Window that Doniol, Bazin and the others had even put in the layout. I did some proofreading but then they decided that the special issue on Hitchcock would only take in account the films made up until Dial M for Murder. It was just a small analysis of the spatial relations in Rear Window. So, if I learned anything on space, it comes from there as well. Ozu I discovered very late. When we arrived in Berlin with Not reconciled, an old German was always saying to me: “Ozu, Ozu”. I told him I didn’t know Ozu, and answered “Mizoguch, Mizoguchi”, because I had seen his films before leaving Paris, and I knew Sansho, O’Haru and Street of Shame very well. You know what Mizoguchi said to Ozu? It’s the most beautiful compliment a filmmaker can give to another filmmaker. Responding to someone who was critisizing Ozu, Mizoguchi said “Yes, but what Ozu does is perhaps more difficult than what I do.” The other beautiful compliment was made by John Ford. An American journalist asked him which filmmakers he admired. And he said “Renoir, for example.” And the journalist: “Ah, Renoir, La Grand Illusion, but what other Renoir films? – But all of them!” He certainly hadn’t seen them all. To come back to Mizoguchi, if I have something in common with him, it’s a certain anger that you don’t find in Ozu’s work. Mizoguchi is all the same the greatest Marxist filmmaker. There are other films I admire a lot, like Monsieur Verdoux, films that have certainly left traces. In Limelight, in the big number with Buster Keaton, after a few seconds Chaplin cuts the sound. At the beginning there is off-screen applause that is perfectly cinematic, reconstituted, invented. But Chaplin had such an experience with theaters and audiences that, abruptly, he cuts everything. And each time the movie theater takes over.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Translated by Stoffel Debuysere (Please contact me if you can improve the translations).

In the context of the research project “Figures of Dissent (Cinema of Politics, Politics of Cinema)”

KASK / School of Arts