“Know that today’s struggle not only relates to the choice of subject, but also to the point of view” wrote Serge Daney in 1974. What is this notion of “point of view” which seemed to be so central to the film critical discourse of that time? And what has become of it? Daney’s statement is part of a piece in which he tried to redefine the “critical function” of the Cahiers du Cinéma, after having failed to set up a Marxist-Leninist inspired “Revolutionary Cultural Front”. It was the realization that the Cahiers of 1972-1973, this short period when radical politics was the order of the day, had not provided any effective support to the ongoing struggles, that led to a reexamination of the question: “how can we intervene?”. The answer, for Daney and his peers, was to delve deep into the relation between theory and practice, or, to use their favored concepts, between “énoncé” (the enounced statement) and “énonciation” (the enunciation). How could this relation be thought of, both for films in which the first predominated (in traditional television documentaries, for example) and those in which the latter prevailed (particularly in the so-called “films d’auteur”)? Going beyond the typical militant content-based criticism, which mainly consisted in assessing the truth or falsety of given statements, implied rethinking the esthetical dimension, not as something automatically derived from the political (as had been the case the years before), nor as something equivalent to it (as it had been for the first generation of Cahiers writers, for whom “form was never neutral”), but as something “secondary”. The question of the “point of view” then involved a concrete examination of how a political worldview could be conveyed through a chosen cinematic presentation. Against the suppositions surrounding militant cinema, all too often considered as a pretext for debate and cognizance, form once again became something to reckon with.

For quite a while the main concern for the Cahiers du Cinéma was the mise-en aspect of mise-en–scene, which was assumed to be largely obscured by the consistency of the scene. For Pascal Bonitzer, this meant that more attention had to be given to what happens “off-screen”: the blind spot where the power of the invisible lies, or to use Althusser’s expression, “the internal shadows of exclusion.” According to Bonitzer, criticism could not only be a matter of making sense of denotations (what is evident, immediate and functional in the cinematic image), the main challenge was rather to uncover the underlying (often ideological) connotations: “Criticism consists in adding meaning, in exhibiting a latent content, revealing overdeterminations [surdéterminations]: in enunciating – in order to bear judgment on it – what the object of criticism eludes, disavows or half-says.” Or as Daney has written, inspired by Barthes: “every film is a palimpsest.” This implied that one had to look beyond the self-sufficient integrity of denotations (they always loathed the idea of naturalism at Cahiers – as they would say: “the represented is not the real”, and the other way around) and take in consideration the surplus-meaning [un plus de sens] or left-over meaning [un restee de sens]. With this assertion Bonitzer explicitally took position against the legacy of the previous Cahiers generation, who had based their notion of “politique des auteurs” precisely on the rectitude of denotation. What had happened then with denotation? “It ages, fades, changes. What do we see today in the same Hollywood films? Connotations. John Wayne no longer ‘denotes”, he ‘connotes’.” Cleary, in the face of political contestations and in line with the new critical theory of the time (from Lacan to Barthes, from Bataille to Foucault via Althusser), film criticism had to take on another function: it could no longer innocently ponder the surface of cinematic worlds, it had to pierce through it, uncover its veil and reveal the workings of the real world. Always a secret beyond the door.

Not that the “politique des auteurs” was dead and buried. For Daney, by thinking of criticism solely in terms of connotation and denotation, something essential was left out: “By seeing in the iconic content of the image only what can be passed – or decanted – from the realm of connotation to the realm of denotation, one leaves aside the simple fact that in the present of the film projection something (but what?) functions as an instance that says ‘Here it is’ (Voici). Something, someone, a voice, an apparatus gives us something to see.” Here Daney draws heavily from Christian Metz’ Essais sur la signification, in which he pointed out that a shot of a gun would have to be “translated” as “voici, here is a gun”. With this indication the attention is shifted to the subject of enunciation, which is not the same as the subject of the statement. It means there is always a point of view that prevents a cinematic presentation to be reduced to a simple statement (or, in Metz’ logic, to a single word). The question of enunciation is then: who or what is this hidden instance, this voice silently saying ‘here it is’, this “little machine wound up to repeat the Lacanian phrase: ‘You want to look? Well, look at this’”? It is a question that is always connected to one of power: “as long as an image is alive, as long as it has an impact (ideologically dangerous or useful), as long as it hails an audience and gives pleasure, that means that in this image, around it, behind it, something that partakes of enonciation is at work (power + event = ‘Here it is’).” For some time this question of power – Who wants and allows this image? Who does it serve? – was lightly to be answered with “the bourgeoisie”: those who were not only supposed to have the monopoly on images of reality, but also on the pre-existing mise-en-scene of this reality. In line with the Althusserian idea of ideology as a system of representations, reality was considered as always already coded, and the challenge for any filmmaker was to look for a new mise-en scene, a new “point of view”, not to reproduce or naturalize reality but to construct one anew: “realism must always be overcome”.

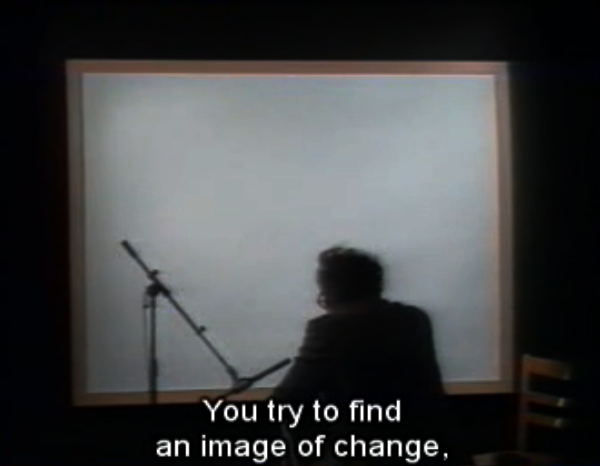

After the mid 1970’s, when the dreams of many turned out to be shattered, the problematics of the “point of view” persisted, provided that it became once again a question of morality. André Bazin was back in the game, as if he had never been gone. And so was the “author”, with a vengeance: it was no longer what happend on the screen that mattered, as much as what could be recognized as the maker’s intentions. Subsequently, the old denotation-connotation scheme, which had come in handy to decipher over-coded ideological vehicles, no longer was of much use. It was no longer a matter of determining the power in or behind the image, but rather of negotiating the power inherent in the relation between those filming and those being filmed (after all, before it is given to see, an image is taken). The search for a position became one of speaking from the right place, of not speaking in the place of others. It is this problematics that Godard has pushed to its limits in Ici et Ailleurs, which is essentially a film about the act of restitution, about the impossible attempt to return images to those they have been taken of/from. This problematics is also at the heart of the films of Johan Van der Keuken, who has consciously kept on looking for the “wrong place”, for situations in which the “unequal exchange” implicit in any filmic contract, was most tangible. Van der Keuken not only tried to confront the unequal exchange between those taking images and those whose images are taken, but also between two ways of being “too much”: the structural, scandalous excess of the dispossessed, and the individual, contingent surplus of the filmmaker. In contrast to Godard, whose feeling is one of overwhelming guilt, Van der Keuken’s was rather one of shame: shame of being somewhere without a particular reason, shame to disturb those who are there without exactly knowing why. Alain Bergala once wrote that VDK’s practice had “less to do with the famous instant of decision than with a state of indecision.” Taking images, for him, was first of all an arbitrary act, determined by the contingency of his position, more than by the prominence of a subject or an instant. This indecision is balanced by continuously re-adjusting the frame, capturing the subjects in their own disadjustment. It stems from an awareness of the impossibility of capturing everything in the image of others: it always contains too much or too little for sense and presence to concincide. The image always resists, Daney said, the little of the real it contains doesn’t let itself be reduced to the cause it serves or the statements it holds. What can be done, as JVK did, is to make this inability visible: continually framing, never enclosing.

The question of inequal exhange is not about having a good or bad conscience in the face of the misery of the world, it is about showing respect in regards to pain and injustice. Between compassionate representation and estheticising indifferentism, wrote Jacques Rancière, “one has to establish the right interval, to put the right distance in the frame, one that stresses the dimensions of injustice and preserves the civility of pain. The image has to be right in the representation of this injustice that is hidden and this pain that is silent.” The immensity of injustice should not be enclosed in compassionate images, the pain of others should not be used as a mirror: one has to find a intermediary distance “where the image doesn’t promise too much beyond what it can maintain or doesn’t take too much beyond what it can return.” The ethical respect for pain and injustice becomes an esthetical search for the right distance, for a frame that is at the same time fitting and unfitting, adjusted and maladjusted to its subjects. It is always the ethics of the point of view that is at stake, or what JM Straub has referred to as einstellung: “Each image is a frame, and each frame is what the Germans call an Einstellung: which means one has to know how to situate oneself in regards to what is shown, at which distance, and at which distance of refusal and fraternity… It is a point of view on the world, touching upon moral and political opinions. One has to know how to einstell in relation to what one films and what one will show. If not one is just an irresponsable artist.” This ethics not only applies to militant or ethnographic film, as one would think; as Godard and others have persistently tried to tell us, it concerns the very act of filming itself. What else could his famous doxa “a tracking shot is a matter of morality” – later taken up by Daney in his ‘tracking Shot in Kapo’ – mean than the idea that one should never put oneself – filmmaker as well as spectator – where one doesn’t belong. The question today is if cinema can still entertain the issue of “point of view”, in a time when morality is all too often mistaken for moralizing, when faithfulness all too often serves as surrogate for respect, and the art of showing is all too often taken for an act of displaying.