Courtisane Festival 2014, 2 – 6 April 2014

“Each generation must, out of relative obscurity, discover its mission, fulfill it, or betray it.”

– Frantz Fanon

An anthropological mockumentary, a baroque anti-symphony, a surrealist counter-ethnography, a revolutionary musical comedy, a porno-misery parody and a cubist road movie. What do all these films have in common? At first sight hardly anything, except for the fact that they all seem to be rooted in a world that is still classified “third”, a world marked by broken promises and shattered dreams, haunted by the spectres of colonialism and the realities of imperialism. These films are distant echoes from a time when a roaring call for a “third” cinema was resounding, one that could expose cruel realities and chase away unwanted ghosts: a cinema of liberation, not owing anything to the workings of the dominant order; a cinema of opposition, found on the outer edges of the overdeveloped world, always South to someone else’s North. These films are all that, and they are not. They do speak of the incoherence of underdevelopment and the discards of colonialism, and yet they refuse to conform to the imperatives of urgency and pedagogy that are bound up with these motives. They do take position against established powers and manifest a desire to overcome the past, but also resist any prescribed directions and prefer to reimagine unforeseen futures. They struggle hard to look for identity, but they do so through the very dismissal of the identities that are imposed by others. Outrageous, hilarious, vertiginous, delirious: this is a cinema that has nothing to lose, and everything to gain; a cinema that chooses to forsake the trodden pathways, only to find itself in a state of complete sovereignty. In all their dislocated intensity, unfathomable glory and impossible hope, this is the stuff that foolish dreams are made of.

In collaboration with the Royal Belgian Film Archive. In the framework of “Figures of Dissent (Cinema of Politics, Politics of Cinema)” (KASK/HoGent).

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

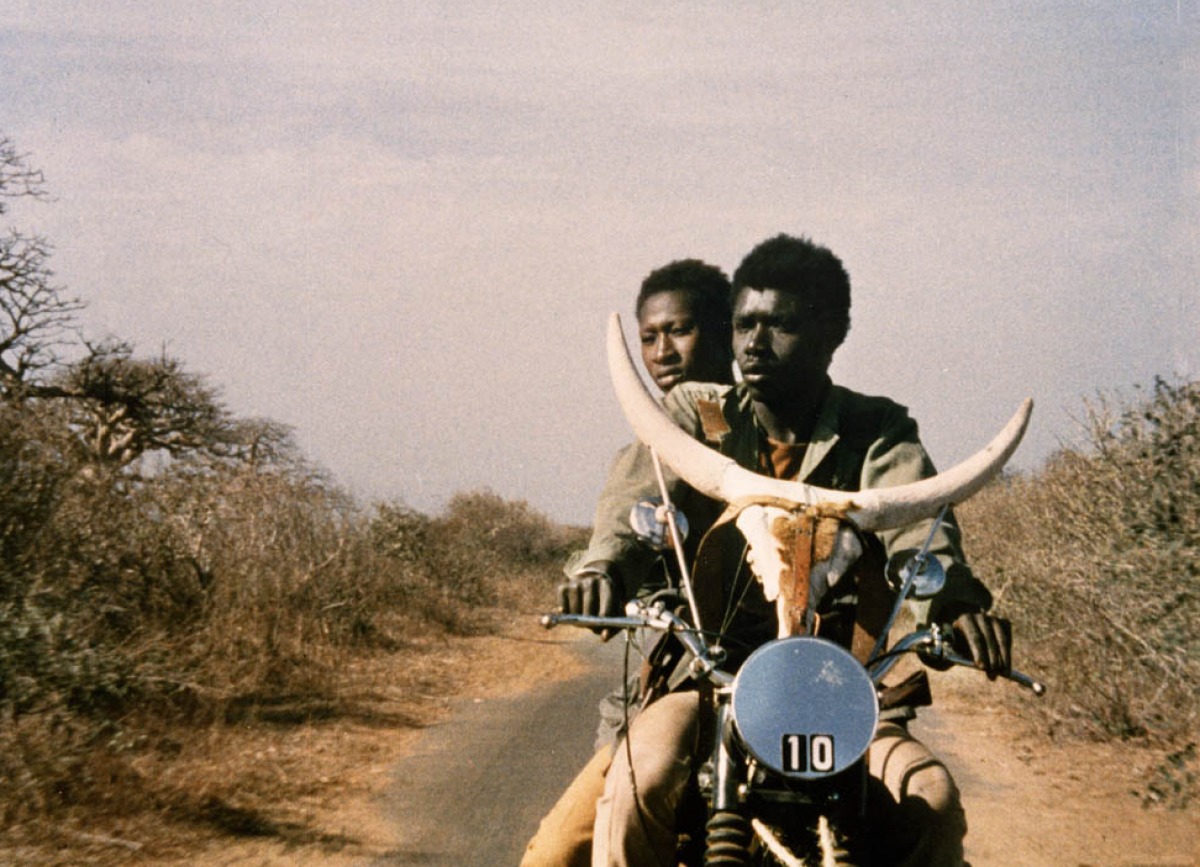

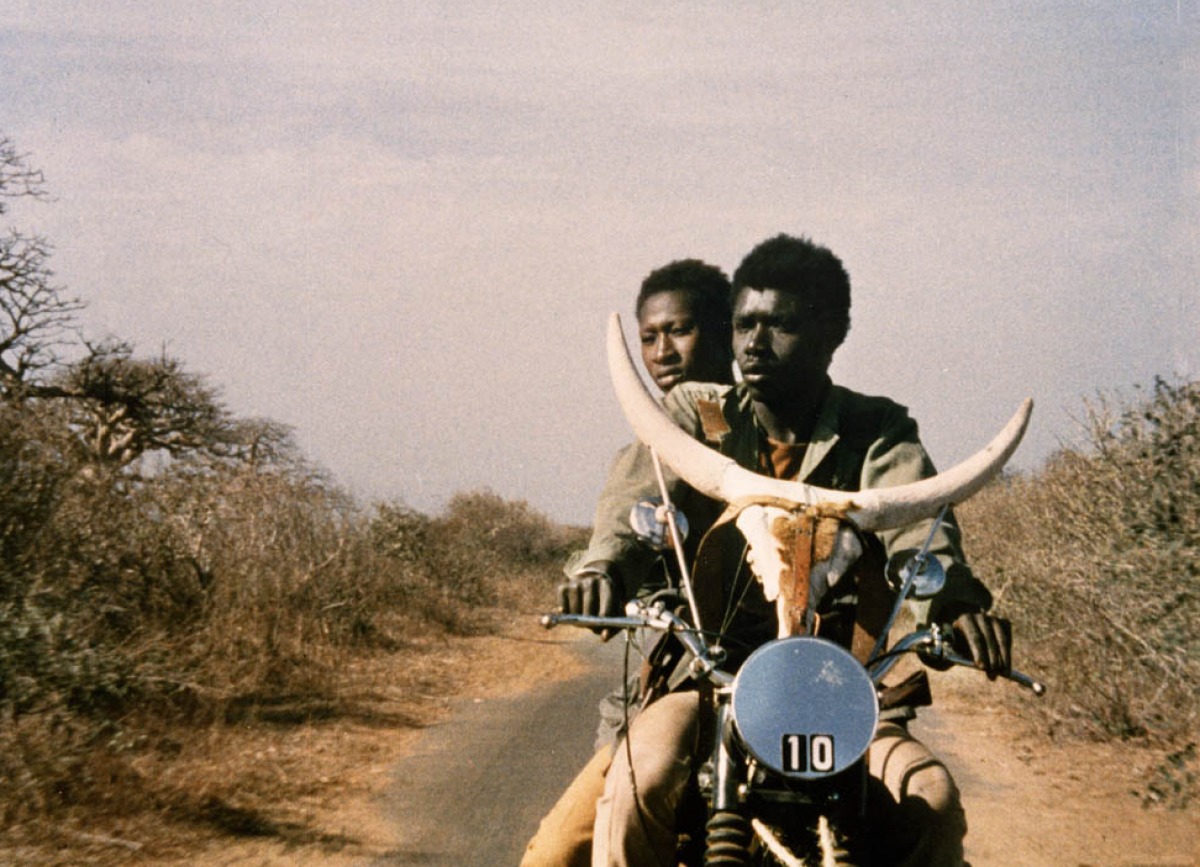

Djibril Diop Mambéty

Touki Bouki (The Journey of the Hyena)

SN, 1973, color, Wolof spoken with English subtitles, 35mm (restored), 95’

“That’s the way I dream. To do that, one must have a mad belief that everything is possible – you have to be mad to the point of being irresponsible. Because I know that cinema must be reinvented, reinvented each time, and whoever ventures into cinema also has a share in its reinvention.“

– Djibril Diop-Mambety

Touki Bouki portrays the wanderings of Mory and Anta, who roam all over Dakar in pursuit of their dream of escaping to France. “The story of Touki Bouki goes back centuries: men have always set out for new lands where they believe time never stops… Only few adventurers seem to make it, but that has never stopped anyone… Djibril left his country with the dream of finding success and solace in Europe. He soon discovered, however, the cruelty of life. While his dream fell apart little by little Djibril found he was unable to leave “Europe”, his host country. That was when returning to Africa became the real dream for him. Ending his days in Africa was a dream he would never fulfill. Touki Bouki is a prophetic film. Its portrayal of 1973 Senegalese society is not too different from today’s reality. Hundreds of young Africans die every day at the Strait of Gibraltar trying to reach Europe (Melilla and Ceuta). Who has never heard of that before? All their hardships find their voice in Djibril’s film: the young nomads who think they can cross the desert ocean and find their own lucky star and happiness but are disappointed by the human cruelty they encounter.” (Souleymane Cissé)

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Kidlat Tahimik

Mababangong Bangungot (Perfumed Nightmare)

PH, 1977, color, Tagalog spoken with English subtitles, 16mm, 93’

“Maybe I’m just an accumulator of images and sounds and then I make a tagpi-tagpi [patchwork] and sew them together. I just work with images and I put my sounds on them and then I release a flow of thoughts and start juggling the sequences back and forth. I don’t try to find surrealist images even in the way as it happened in Perfumed Nightmare. I was a madman when I was making that film and I still am.”

– Kidlat Tahimik

For his first film, Kidlat Tahimik (meaning “quiet lightning” in Tagalog) drew on his own experience living “in a cocoon of Americanized dreams” for this tale of a village jitney driver, faithful student of Voice of America and its many lessons, and founder of his local Werner Von Braun fan club. Kidlat hopes to become an astronaut, or at the very least to strike it rich in the promised land. He makes it as far as Europe, where a series of rude and comical awakenings unfolds and Kidlat learns that the modern Western world is far from paradise. Tahimik, who later became a protégé of Werner Herzog in Munich, is a faux naif who uses the genuine naiveté of his hero – like Chaplin’s Little Tramp – to inscribe a powerful portrait of the American colonization of Filipino dreams. But, like the charming, festooned “jeepny” Tahimik constructed from an abandoned U.S. Army vehicle, the film creates something wholly original and imaginative from the discards of colonialism. In the words of Susan Sontag: “ Perfumed Nightmare makes one forget months of dreary moviegoing, for it reminds one that invention, insolence, enchantment – even innocence – are still available on film”

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Arthur Omar

Triste Trópico

BR, 1974, color, Portugese spoken with English subtitles, 16mm to video, 75’

“I am fascinated by sound interference and remixes, ultra-editing, blending, everything that goes beyond the immediateness of the image and the verbal. Words, depositions, speech; for me it’s all raw material to be modulated. I’m not interested in anything that preexists the images, but the production of an experience through the image, in the image, like a chemical reaction in the brain, that can only occur there.”

– Arthur Omar

The biography of an imaginary doctor who left Brazil to study in France where he became friends with André Bresson, Max Ernst, and Pablo Picasso, and somehow ended up as an indigenous messiah. “A galaxy of discontinuous images. With a new presentation of the conflict between the coast and the sertão, Triste Trópico proposes a criticism, full of irony and hallucination, of the anthropological discourse in the tropics. Its main character, a surprising petit bourgeois doctor, embarks on a journey that will invert the sense of Levi-Strauss demarche, as expressed in his book Triste Tropique. The allegory of Cinema Novo was conceived as an unveiling, whereas the allegory of Triste Trópico is a movement towards opacity, and what poses a problem is the very act of reading. Triste Trópico is meta-cinema and, from this point of view, it is different from the forms of anti-colonialism of the 70s in Brazil”. (Ismail Xavier)

DUE TO THE UNAVAILABILITY OF A COPY OF ‘TRISTE TROPICO’, THE FILM WILL BE REPLACED BY ‘HOW TASTY WAS MY LITTLE FRENCHMAN’

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Nelson Pereira dos Santos

Como era gostoso o meu frances (How Tasty Was My Little Frenchman)

BR, 1971, 35mm, Tupi, French and Portuguese spoken with English subtitles, 84’

“The government broadly financed historical films, but it wanted the history to be within official parameters – the hero, the father of the country, all those things we have been told since elementary school. I made How Tasty Was my Little Frenchman, which does not correspond in any way to the official vision of history, under these circumstances. The film was not even considered to be historical, but rather purely fictional, as if official history were not fiction.”

– Nelson Pereira dos Santos

Jaundiced cultural allegory dressed up as anthropological re-creation, How Tasty Was My Little Frenchman slyly links Montaigne’s who-are-the-real-savages query to Brazil’s military dictatorship. Pereira draws from multiple historical sources—especially German explorer Hans Staden’s 1557 memoir—to tell the story of a French soldier’s experience as a captive of the cannibalistic Tupinambá tribe. “Pereira constructs a comic horror film in which sixteenth-century intertexts are read as current events in an analogy of colonialism with global capitalism. This film is Pereira’s response to Brazil’s building of the Trans-Amazon Highway, in the course of which contact with indigenous communities was made that threatened them with near extinction. The current destruction of habitat and native populations recalled to Pereira the traumas of colonization…The ingesting of foreign invaders thus becomes for Pereira a metaphor for indigenous resistance to global capitalism, the most recent form of economic colonization.” (Virginia Higginbotham)

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Carlos Mayolo & Luis Ospina

Agarrando pueblo (The Vampires of Poverty)

CO, 1977, color & b/w, Spanish spoken with English subtitles, 16mm to video, 28’

“In the early 1970’s there appeared a certain type of documentary that superficially appropriated the achievements and methodologies of independent film to the point of deformation. In this way, poverty became a shocking theme and a product easily sold, especially abroad, where it is the counterpart to the opulence of consumption… We made a kind of antidote or Mayakovskian bath to open people’s eyes to the exploitation behind the miserabilist cinema which turns human beings into objects, into instruments of a discourse foreign to their own condition”.

– Carlos Mayolo & Luis Ospina

Filmed in Cali and Bogotá, Agarrando pueblo follows an unscrupulous film director as he and his cameraman wander around the cities looking for unwilling subjects for a documentary commissioned by German television. “Deliberately detached from the accusatory militant left, Luis Ospina and Carlos Mayolo launch in 1978 what could be called their cinematic-political thesis: Agarrando Pueblo (The Vampires of Poverty), an outrageous protest of national and international documentary models, which at the time – and even today – shamelessly exploited all kinds of third-world suffering (referred to by the directors as “poverty-porn”) and exported it to European television stations and festivals. Counterinformative from beginning to end and in every sense of the word, the film mixes staged and real scenes of a typical film crew commissioned by a Germany television channel to seek out archetypical social horrors, trampling over the basic principles of professional ethics, the meaning of information and – naturally – sociological research.” (Isleni Cruz Carvajal)

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Med Hondo

West Indies (ou les nègres marrons de la liberté / The Fugitive Slaves of Liberty)

MR/DZ, 1979, color, French spoken with English subtitles, 35mm, 113’

“For too long a time, African cinema has been conceived as a poor cinema, a cinema of approximations where techniques did not match ideas … Militant cinema can thus be beautiful and rich … Indeed, West Indies … is no more a West Indian film than an African film. It is a film which summons all the people whose past is made out of oppressions, whose present is made out of aborted promises and whose future is left to be conquered.”

– Med Hondo

A single-set color musical tracing the history of the West Indies through several centuries of French oppression. “Med Hondo’s West Indies is a revolutionary musical in both senses of the word. This witty, scathing production offers an angry view of West Indian history, using imaginative staging and a fluid visual style. The film’s single set is an enormous slave ship [built in an unused Citroen factory in Paris]. Mobile camerawork and frequent narrative shifts take the actors through various vignettes about French colonialists invading the Indies, Carribean natives lured to Paris, the process by which the islands were first settled and a lot more. The material has the potential for overbearing irony but Mr. Hondo has a light touch. With cast members rotating their way through many different roles (the same actors may play slaves, then worried island villagers, then displaced West Indians)… Mr. Hondo leads the film through a long series of well-connected tableaux, culminating in an almost joyous call to arms.” (Janet Maslin)

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

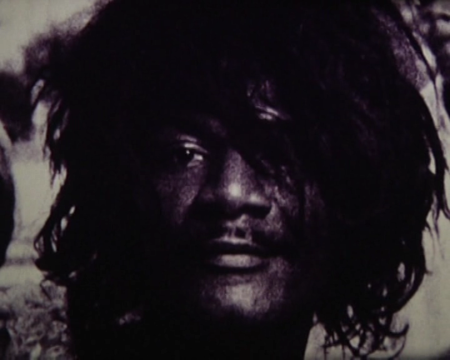

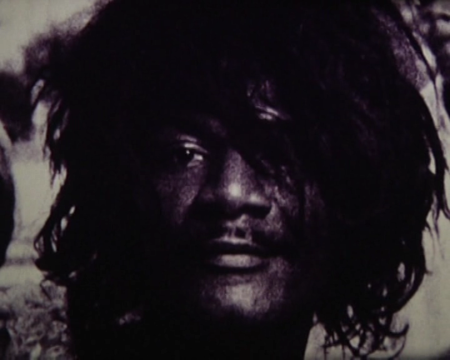

Glauber Rocha

A Idade da terra (The Age of the Earth)

BR, 1980, color, Portugese spoken with English subtitles, 35mm, 152’

“The film develops the same ways, principles, lines, desires of justice and humanism in a world getting more and more destroyed by violence. The film is a barbarous mass, not a civilized mass. Because in substance of cinematographic language, montage, structure, everything was remade, subverted, reorganized. It is a baroque, reconstructivistic style, a very new thing that the Brazilians who saw the film adored.”

– Gauber Rocha

Catholic rituals and Afro-Indian gods, rural mysticism and revolutionary politics, Brahms and Villa-Lobos: this last film by Glauber Rocha, angel-demon of the Brazilian “Cinema Novo”, defies every attempt at unequivocal classification or definition. “It’s not to be told, only to be seen”, he said. A torrential, hallucinatory anti-symphony, a terrifying cry of desperation, a destruction in progress. “He hit himself against the impossible, the impossibility of being a great filmmaker of the Third World, a great black filmmaker. The Age of the Earth is the film of the Third World, there is no other. The others are films that join other films. The Age of the Earth is a great impossibility, a passage through world and time, a discovery of America on the opposite lane, a black Battleship Potemkin, or rather, it informs, full of gestures and rhythm, an extreme anti-classic – a spitting of blood in the face of the current cinema, dominated by sweetness.” (Pascal Bonitzer)