By Jean-Luc Godard

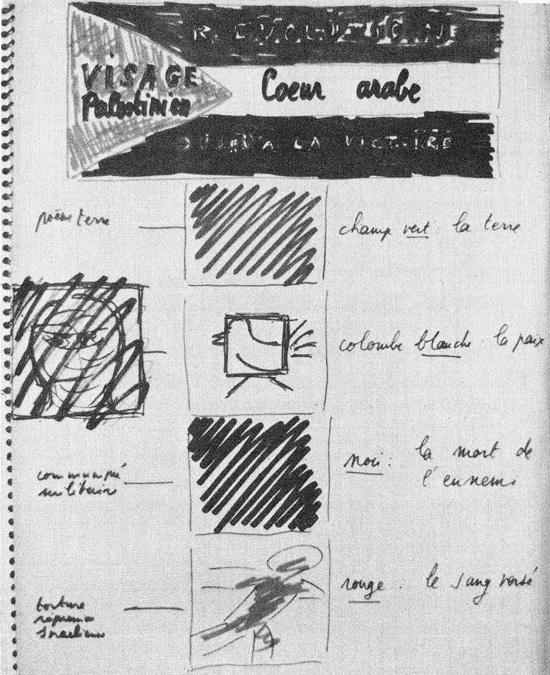

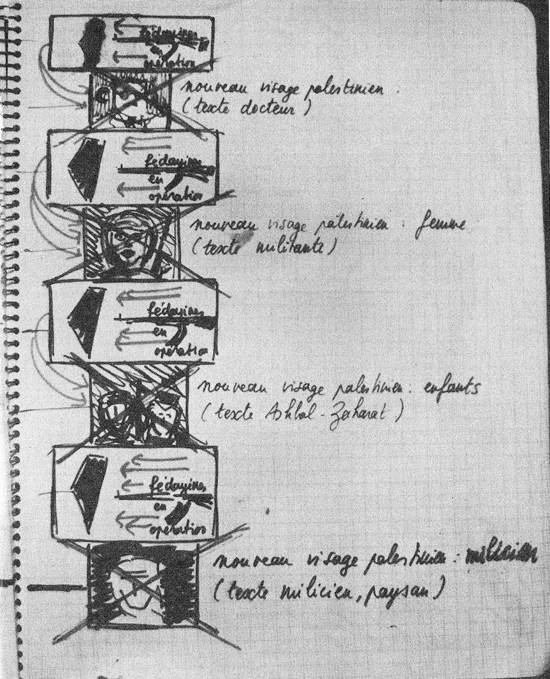

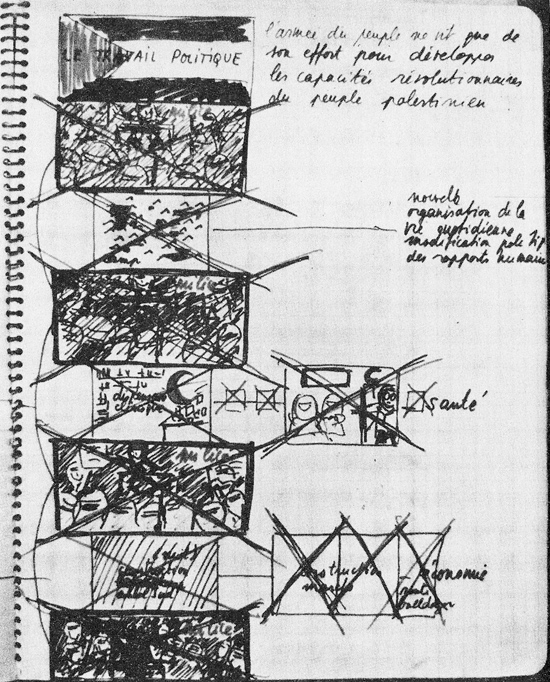

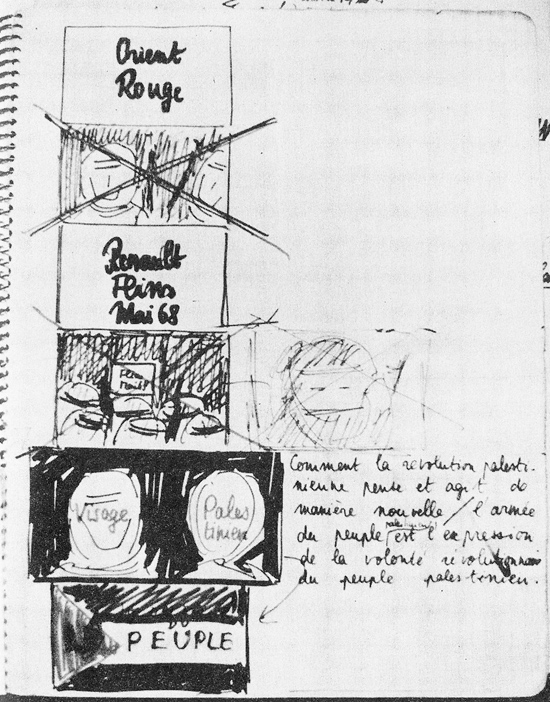

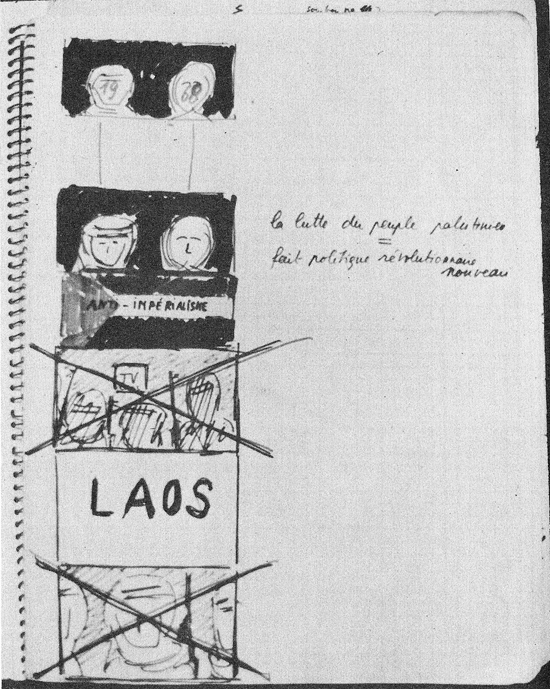

Originally published in ‘El Fatah’, July 1970, without title. Another translation was published in ‘Free Palestine’, January 1971. The text was written while Godard and Jean-Pierre Gorin – as the Dziga Vertov Group – were working on a film documenting the Palestinian struggle. The footage was used as the basis for ‘Ici et Ailleurs’, which was released six years later and served as a critical reflection on some of the ideas evoked in this text. Drawings are taken from Godard’s shooting notebook, found in Michael Goodwin & Greil Marcus, ‘Double Feature’ (Outerbridge & Lazard, 1972)

We found it more appropriate, politically speaking, to come to Palestine, rather than to go elsewhere: Mozambique, Columbia, Bengal. The Middle-East has been directly colonised by the French and English Imperialisms (the Sykes-Picot treaties). We are French militants. It seemed more appropriate to come to Palestine because the situation here is complex and unique. There are many contradictions and the situation is less obvious than in South-East Asia, at least in theory.

Our tasks, as artists who are struggling today through cinema, are still on a theoretical level. To think differently in order to create revolution… that’s where we’re still at. We are several decades behind Al-`Asifah’s first bullet (1).

Mao Zedong says good comrades go where the difficulties are, where the contradictions are at their peak. To make propaganda for the Palestinian cause, yes. With images and sounds. Cinema and television. To make propaganda is to spread problems over a carpet. A film is like a flying carpet that can go anywhere. There is no magic. It’s political work. One has to study and search, record this research and this study, and then show the result (the montage) to other fighters. Demonstrate the fedayeen’s struggle to their Arab brothers who are being exploited by the bosses in the French factories. Show Fatah’s militiawomen to their sisters of the Black Panthers who are being chased by the FBI. Make a film politically. Show it politically. Distribute it politically. It’s long and hard. It’s solving a concrete problem every day. Finding a fedaï, an officer, a militia member, figuring out together how to create images and sounds of their struggle. Telling them: “I will film an image of you shooting Al-`Asifah ‘s first bullet.” Knowing which image should come first, and which one should follow, for the whole to have a meaning. A political, revolutionary meaning – that is to say which helps the Palestinian revolution, which helps the global revolution. All of that is long and hard. One has to know what is cinema…, what information for Fatah means, and what the contradictions with the other organizations are. Fatah, for example, fights against American Imperialism. But American imperialism is also the New York Times and CBS. We, we are fighting against CBS. There are a lot of journalists who sincerely consider themselves as leftist, and who are not fighting CBS and the New York Times. They may think they are helping Fatah by publishing an article in the bourgeois press. But they are not fighting. It’s Fatah who is fighting and working. It’s the fighters of Fatah who are dying. One has to really see that. Literature and art, fighting on two fronts. The political front and the artistic one: this is the present stage, and we have to learn to resolve the contradictions between these two fronts. In the newspaper published by Fatah, we still see too many pictures of leaders and too little of fighters. One has to see where this contradiction is situated, and how to resolve it. It’s not an artistical problem of layout. It’s a political problem in the ideological domain (the press). We have to learn how to fight the enemy with ideas, not only with guns. It’s the Party commanding the gun, and not the other way around (2). And the complexity of the Palestinian struggle is connected to the difficulty of constructing the Party here (like in France). The originality of Fatah, even before the Suez Canal was overtaken, is that it refused to call itself a Party or a Front. It’s about saying to a Musulman: “don’t abandon your ideas, just leave your organisation, and join our ranks.” The Fatah does not need to be Marxist in words, because they are revolutionay in facts. They know that ideas change along the way. That the longer the way to Tel-Aviv, the more the ideas will change, which will finally lead to the destruction of the state of Israel.

Political front and artistic front

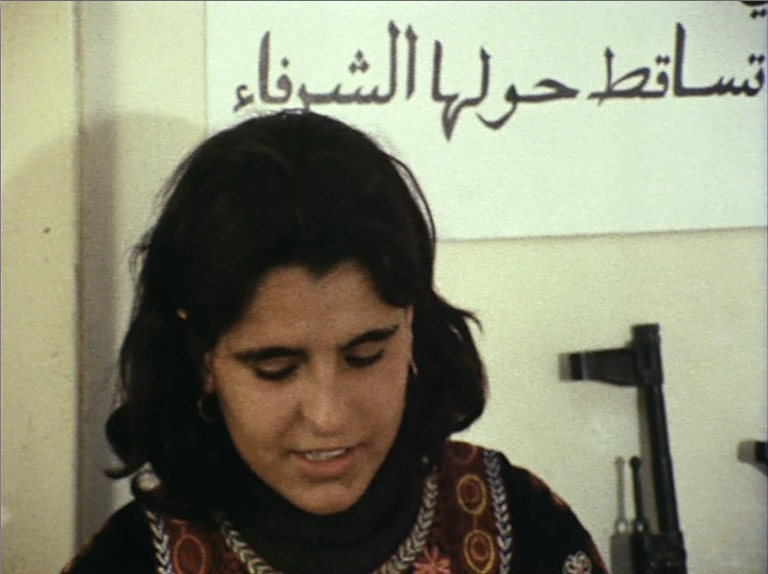

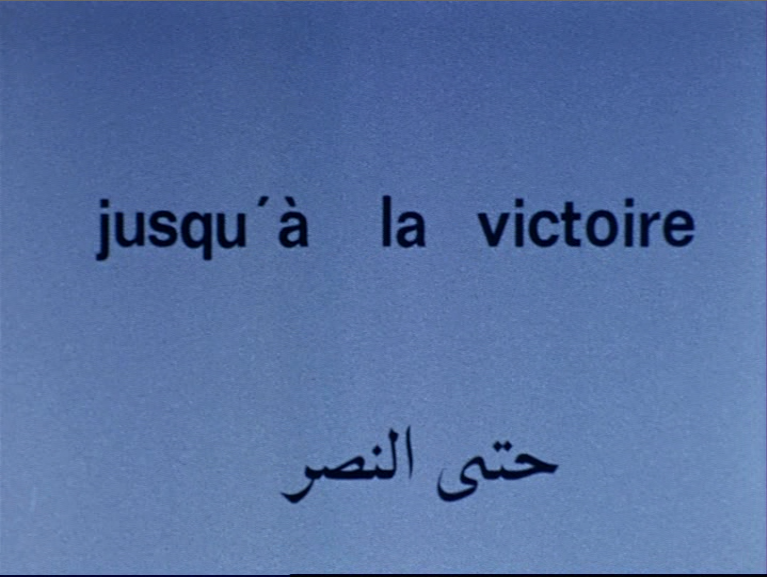

We have come here to study: to learn lessons, if possible to record these lessons, to distribute them here, or elsewhere in the world. Almost a year ago, two of us have come to investigate the Democratic Front. Then an other went to Fatah. We have read the texts and the programs. As French maoists, we have decided to make the film with Fatah and its title would be Jusqu’à la Victoire. We have the Palestinians say the word “revolution” in the film. But the real title of the film is The methods of thought and action in the Palestianian liberation movement. With the comrades of the democratic front, we have the same discussions as with militants in Paris. We learn nothing. Not them, nor us. With Fatah, it’s different. It is very difficult to talk to a leader about the image that has to be created of the Palestianian revolution, and about the sound that has to accompany (or contradict) this image. But it is exactly this difficulty that is positive. It poses in concrete terms the contradiction between theory and practice: between political front and artistic one.

When we arrived in Amman, we were told “what do you want to see?” We answered “everything!”. We have seen the Ashbals, the training of the militia, the bases in the South, the North and the Centre. We have seen the school of martyrs. We have seen the school of officers, the medical centers. Then they told us “what do you want to film now?”. We said “we don’t know” – “How come you don’t know?” – “No, we would like to talk, study a bit with you. You don’t have a lot of munition for the Kalachnikovs and RGB’s. We don’t have many images and sounds. The Imperialists (Hollywood) have ruined or destroyed them. So we can’t waste them. They are ideological munition. We have to learn to use them to kill the enemy’s ideas. That’s why we need to talk with you”. – “fine, with who would you like to speak?” We said: “with Abu Hassan (3)”. We didn’t know who he was, but we had read one of his article in the first issue of Fedayin. He talked to us. Politically. For example, he said: “the people’s army does not consist of sophisticated radars. They are 10.000 children with binoculars and walkie-talkies.” That is a revolutionary image. Straightaway, we see that the Egyptian army is not an army of the people. Instead of 10.000 children, there are 10.000 Soviet instructors.

The bullet close to the ear

Abu Hassan also said: Al-`Asifah ‘s first bullet has to be fired close to the ears of the farmers, so that they can hear the sound of liberation of the land. That is a revolutionary sound. That is a discussion which allows to establish political relations between an image and a sound, rather than simply making images that are so-called “real” but mean nothing, say nothing because they have nothing to say, nothing that we don’t know already. And what use is it to say what we already know? In any case, not for the revolution looking for the new behind the old. That takes time. It’s long and hard. But there is no reason for a film of the Palestinian revolution to not encounter the difficulties of this revolution. Why would this film be shown on American television? Does Fatah control the Yankee tv stations? No, they don’t even control the cinemas in Amman. They control Amman. But every night, in the dark cinemas, the imperialist rottenness blinds the masses. Luckily, the morning after the June crisis the unified Commandment was able to reopen their eyes by publishing a newspaper henceforth (4). The problem of revolutionary information is a very important one. We say: “cinema, secundary task of the revolution for us currently in France.” But we make this secondary task our primary activity. Let us look, then, at this contradiction between this secondary task and the primary task of the revolution, which is, here, the armed war against Israel. Let us also look at the other contradictions between cinema and the other secondary tasks of the Palestinian revolution. See that at a certain moment, in a given place, the secondary transforms in primary. That is what we call politically posing the fact of making a political film. Not only interviewing Habash or Arafat or Hawatmeh (5). Not only spectacular images of “lion cubs” wading through flames, but relations between images, relations between sounds, between images and sounds that point out the relations, in the Palestinan revolution, between the armed struggle and the political work.

Each image and each sound, each combination of images and sounds are moments of relations between forces, and our task consists of directing these forces against those of the common enemy: imperialism – that is: Wall Street, the Pentagon, IBM, United Artists (entertainment from Trans-America Corporation) etc. For example, we think that Fatah, in the course of the crisis of June, was defeated in the domain of information. With regard to the capitalist European countries, of which the Times, Il Messagero, Le Monde and The Figaro have spoken? Of the response that the masses have given to the deadly provocations of the Jordanian reaction? No. Of the role played by Fatah in waging this response politically and military? No. All these papers, as well as the East-European televisons and radios have blown George Habash out of proportion to the detriment of Yasser Arafat (5). Our task as revolutionary militants of information is also to analyze the why and how of such operations. For Imperialism, it was not only necessary to try, once again, to break down the unity of edification of the Palestinian resistance, but also to deter the sense of its liberation fight in the eyes of the English, Italian, French etc. masses and in doing so hit a one more blow to the revolutionary elements of these masses, for whom the Palestinian revolution, just like the Vietnamese, is a precious ferment. Today, it’s terrible that a text like the one written by Abou Lyad in dialogue with Fatah is not translated in French (6). These are perhaps minor defeats, but still one has to have the revolutionary honesty to analyze them as being defeats: struggle, faillure, new struggle, new faillure, new struggle untill victory, such is the logic of the people, according to the Chinese comrades. Such is also the logic of the Palestinian people in its movement of national liberation under the direction of Fatah. That is what we are trying to show in our film, in your film. Where will the film be shown? This will depend on the actual state of the struggles. It can be shown on a road in a village in South-Libanon. We put up a sheet between two windows, and we project. In front of the students at Berkeley. Amongst workers at strike in Cordoba or Lyon. In a school of Amílcar Cabral (7). That is, in general, it will be projected in front of the advanced elements of masses. Why? Because it represents forces in struggle.

The relations between images

It should be possible to use it, on short or long term, by other elements of these forces on the moment of their struggle. That is to say at the moment when it will useful for their struggle. An example: we show an image of a fedai crossing the river, followed by an image of a Fatah militia woman who teaches refugees in a camp to read, followed by a image of a “lion cup” in training. These three images, what are they? They are a whole. Non of them has value on their own. Perhaps a sentimental, emotively of photographic value. But not a political value. In order to have a political value, any of these three images has to be connected to the two others. At that moment, what becomes important is the order in which they will be shown. Because they are parts of an overall politics; and the order in which we arrange them represents the political line. We are on the line of Fatah. So we arrange the images in the following order: 1° Fedayeen in operation; 2° Militia woman working in a school; 3° children training. Which means: 1° armed struggle; 2° political work; 3° prolonged popular war. In the end, the third image is the result of the two others. It comes down to: armed struggle + political work = prolonged popular war against Israël. It also comes down to: man (triggering the fight) + woman (being transformed while creating her own revolution) who give birth to the child who liberates Palestine: the generation of victory. It’s not enough to show a “lion cub” or a “flower” and say “it’s the generation of victory”. One has to show why and how. An Israelian child can’t be shown in the same way. The images which produce the image of a Zionist child are not the same of those of a Palestinian child. Moreover one shouldn’t talk of images; one has to talk about the relations between images.

The Lebanese lackeys of Hollywood

It’s imperialism that taught us to consider images in themselves, making us believe that an image is real. While common sense shows us that an image can’t be anything but imaginary, precisely because it is an image. A reflection. Like your reflection in the mirror. What is real, is first of all you, and then the relation between you and this imaginary reflection (8). What is real then is the relation you establish between these different reflections of yourself, or these different pictures of you. For example, you say to yourself: “I am beautiful” or “I look tired”. But in saying that, what are you doing? You are doing nothing but establishing a simple relation between several reflections. One in which you seem in good shape, another in which you look less so. You compare, meaning you establish a relation, and then you can conclude: “I look tired.” To make a film politically means establishing this kind of relations politically, in order to resolve a problem politically. Which means in terms of work and battle. And precisely imperialism, in wanting to make us believe that the images of the world are real (while they are imaginary) aims to prevent us from doing what we have to do: establish real (political) relations between these images; establish a real (political) relation between an image of Ashbal training and an image of Fedayeen crossing the river. The only revolutionary reality is that (political) reality of that relation. Political, because it poses the question of power; and a chain of images such as the one we just described declares that power is at the end of a gun. Imperialism would like us to be content with showing a Fedai crossing a river, or a farmer learning to read, or Ashbals training. Imperialism has nothing against that. It produces images like that every day (or their slaves do it at it’s service). Every day it distributes them on BBC, in Life, Il Expresso, Der Spiegel. On one hand there is UNRWA (9) (for the stomach), on the other Hollywood and its Lebanese and Egyptian lackeys of cinema (for the ideas and images that provoke ideas). Imperialism has taught us not to set up a relation between the three images we just mentioned, or perhaps to set it up, but then in a certain order, so their plans wouldn’t be disrupted.

The ideas and the contradictions

And our own task, as militants currently active in the domain of anti-imperialist information, is to fight fiercely in this domain. To liberate us from the chains of images imposed by imperialist ideology, through all their devices: press, radio, cinema, records, books. It’s a secondary task which we have make our principal one, trying to resolve the contradictions this entails. For example, in fighting on the secondary front, we often collide with other comrades. These comrades, here in Fatah for example, have advanced and rightful ideas on the principal front of the armed struggle, and ideas that are often less on the secondary front of information. For us all, it’s about learning how to resolve this contradiction as part of the contradictions within the people. Not contradictions between the enemy and us. To create contradictory images means to make progress on the road of the resolution of these contradictions. And here, after having posed the problem of the production of this series of three images (to take the same example), you can now pose the problem of distribution in a more rightful, more political way. And it’s because these (imaginary) images have a real (contradictory) relation between them, it’s because of this real relation that those who watch and listen to these images will also have a real relation with them. Viewing the film will be a moment of their real existence, of their reality. Political reality, this time. For an oppressed farmers, a striking worker, a revolting student, a fadai carrying a kalachnikov… this is what we would like to say by saying “down with the spectacle, long live the political relation.”

The teeth and the lips

That is how literature and art can become, as Lenin wanted, a small living screw in the mechanisme of revolution. Thus, to sum up, not by showing a wounded fedai, but showing how this wound will help the poor farmer. And to arrive at this is long and hard, because, since the invention of photography, imperialisme has been making films to prevent those it oppresses to make them theirselves. It has made images to conceal the reality from the masses it oppresses. Our task is to destroy these images and learn how to create other ones, more simple, to serve the people, so the people can use of them in their turn. Saying “it’s long and hard” is saying that the (ideological) fight here is part of he prolonged war against Israel conducted by the Palestinian people. It’s saying that elsewhere this fight is connected with all the people’s wars against imperialism and its allies. Connected like the teeth and the lips (10). Like mother and child. Like the land of Palestine and the Fedayeen.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Translated by Stoffel Debuysere (Please contact me if you can improve the translation).

In the context of the research project “Figures of Dissent (Cinema of Politics, Politics of Cinema)”

KASK / School of Arts

translator’s notes

(1) Al-`Asifah was the “mainstream” armed wing of the Fatah.

(2) Godard also used Mao’s formula “the Party commands the gun” in‘La Chinoise’.

(3) Abu Hassan was the code name of Ali Hassan Salameh, who later become known as the chief of operation for the Black September organization.

(4) In June 1970, Palestinian guerrilla groups and the Jordanian army clashed in Amman, but fighting ceased after an agreement was struck allowing Palestinian fighters to continue their presence (until Black September).

(5) George Habash was the founder of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), which defined itself as a Marxist-Leninist movement in 1969. In the same year an ultra-leftist faction under Nayef Hawatmeh split off as the Popular Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PDFLP), later to become the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP).

(6) Abou Lyad or Salah Mesbah Khalaf was deputy chief and head of intelligence for the Palestine Liberation Organization, and the second most senior official of Fatah after Yasser Arafat.

(7) Amílcar Cabral was a Guinea-Bissauan and Cape Verdean agricultural engineer, writer, and a nationalist thinker and politician. Also known by his nom de guerre Abel Djassi, Cabral led the nationalist movement of Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde Islands and the ensuing war of independence in Guinea-Bissau.

(8) This questioning of the “reflection” owes a lot to certain texts by Alain Badiou – notably ”The Autonomy of the Aesthetic Process’ (1966 – written in ’65), which is also quoted in ‘La Chinoise‘ and Louis Althusser – notably ‘Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses’ (1970), which was adapted by Godard and Gorin as ‘Lotte in Italia’ (1969).

(9) Created in December 1949, the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) is a relief and human development agency, originally intended to provide jobs on public works projects and direct relief for 652,000 Arabs who fled or were expelled from Israel during the fighting that followed the end of the British mandate over Palestine.

(10) Here Godard paraphrases Louis Althusser: “class struggle and marxist-leninist philosophy are connected like teeth and lips.”