“ Let nothing be changed and all be different. ” Of all the precepts that Robert Bresson has collected in his Notes sur le cinématographe, this riff on an often quoted historical maxim might be the one that is par excellence applicable to the films of Hong Sang-soo. Since discovering Bresson’s work triggered him to patiently carve out his own singular path through the world of cinema, the South-Korean filmmaker has continued to weave an ever subtly changing canvas of minute variations on the same narrative threads, playfully entwining themes of love, desire, deception and regret.

In Hong’s bittersweet sonatas, typically composed of multiple movements, repeated figures and modulating motives, any relationship or situation is susceptible to variability: there can always be another version, another chance, another time. Some situations present themselves as repetitions, while others accommodate a myriad of storylines that intertwine or parallel each other. Every film contains multiple stories, and is also rich in virtual ones, some yet to be told, others perhaps already told before. Yet for all the doubling, folding and mirroring in Hong’s films, what stands out from their narrative playfulness is hardly a display of virtuosity, but rather, as Jacques Aumont reminds us, a sense of idiocy. This idiocy does not only refer to the innocuous array of trite misunderstandings, misfortunes and missteps that detract characters along divergent or crossing paths, but above all to the sense that everything seems to happen without reason, without a causal or rational order that determines the relations between characters and their environment, between their present and their future. In Hong’s films, there is no particular reason why things couldn’t fall into place differently: every relation entails a multiplicity of relations.

From his feature debut The Day a Pig Fell Into the Well (1996) to The Day After (2017), the latest of four films he has released in the past year, Hong Sang-soo has continuously reinvented his explorations of the very arbitrariness and contingency of life’s connections and directions by crafting his own take on another one of Bresson’s precepts: to find without seeking. While the production of his first films was still based on a predefined screenplay, Hong has increasingly refined his working method into a both intuitive and rigorous process of writing and filming. On the morning of each shooting day, he writes out dialogue for the scenes he intends to shoot, gives his cast time to memorize their lines, determines camera angles, and then starts to shoot – most often using statically framed long takes which are only occasionally interrupted by abrupt zooms. The absence of a prefixed template and a receptivity to what transiently comes into view allows for an unravelling of the concrete everyday into unexpected patterns of visual and narrative features, opening up even the most trivial gestures and insignificant details to a web of indefinite resonances.

Stemming from a wariness of generalizations that claim to be transcendent and all-encompassing, this constant interplay between concrete presence – of the people involved and the environments they occupy – and abstract construction is what, more than anything, propels Hong Sang-soo’s singular cinematic investigations into the dynamics of repetition and difference. It is also what brings his work, film after film, ever closer to the art of cinema as it was once devised by Bresson: as a method of discovery.

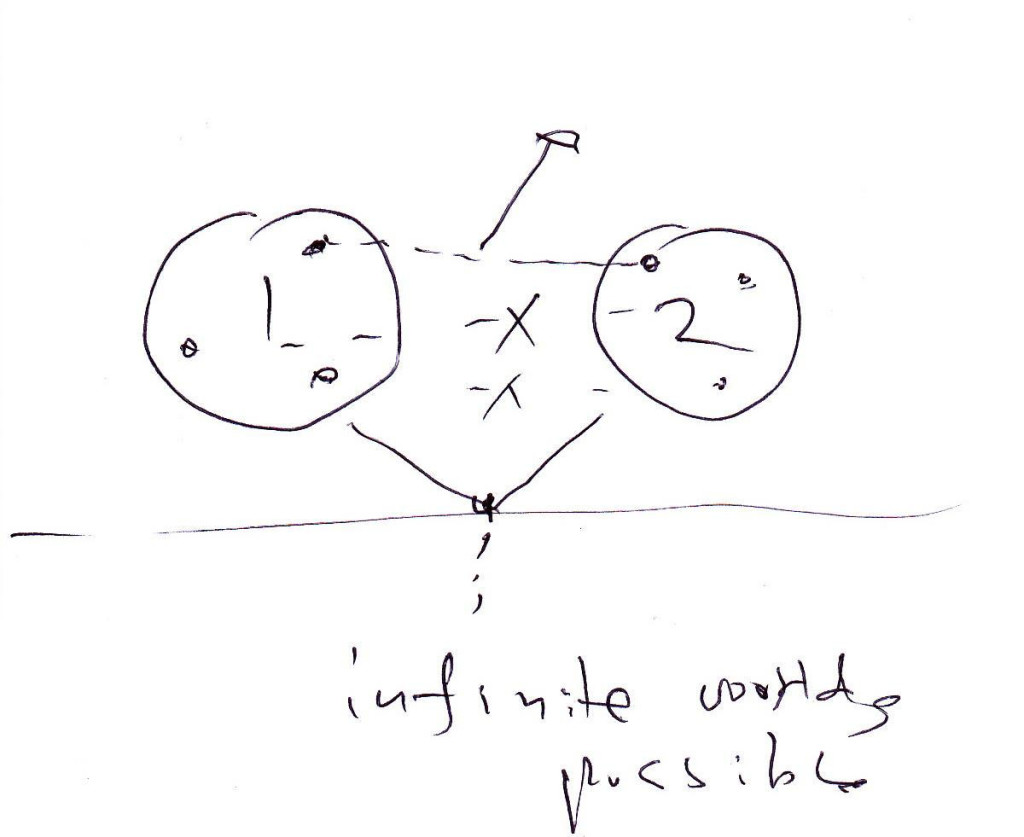

This modest publication, compiled on the occasion of the retrospective of Hong Sang-soo at the Brussels CINEMATEK (January 18 to February 25, 2018), aims to trace the development of Hong’s remarkable body of work through a collection of essays and interviews that were written and published between 2003 and 2017. Assembled here for the first time, they give an enlightening insight into his cinematic universe, which keeps expanding as a variety of variations on an aphorism that he himself has sketched out in one of his drawings: infinite worlds are possible.

Stoffel Debuysere, Courtisane & Gerard-Jan Claes, Sabzian (Eds.)

Published on the occasion of the Hong Sang-soo retrospective in Brussels (January 18 to February 25, 2018), an initiative of CINEMATEK and Courtisane, in collaboration with the Korean Cultural Center in Brussels and Cinea. Program produced by Yura Kwon (Finecut) and Céline Brouwez (CINEMATEK).

Publication compiled, edited and published by Sabzian, Courtisane and CINEMATEK.

Publication available in Courtisane bookshop