2016 / 256 pages / 21 x 14,8 cm

Published by AraMer

This manuscript came about in the framework of the research project Figures of Dissent (KASK / University College Ghent School of Arts, 2012-2016). Research financed by the Arts Research Fund of the University College Ghent.

How can the relation between cinema and politics be thought today? This question was the starting point for Figures of Dissent, a four-year research project that was initiated in February 2012, with the generous support of the Arts Research Fund of the University College Ghent. In an attempt to tackle this vast conundrum, which has been pondered and pontificated upon since cinema’s beginnings, an extensive series of public encounters and screenings was organized in various locations in Belgium and abroad. The principle aim of this series, which came about by dint of a broad network of organizations and institutions, was not to define or illustrate a singular theory that could somehow shed light on this cumbersome relationship, but rather to give impetus to a culture of exchange that would allow for a variety of views and insights to be shared. The challenge taken on was thus not so much to determine how cinematic forms might be able to measure up to political ideas or ideals, but rather to create resonance spaces that could give expression to the infinity of resistant emotions, perceptions, movements, gestures and gazes that the universe of cinema has to offer. Not in order to learn how to decipher and calculate the meanings that might inhere in them, but simply to bring about a circulation of sense, a circulation of fictions and frictions that might have their own role to play in the rearrangement of our sensible world.

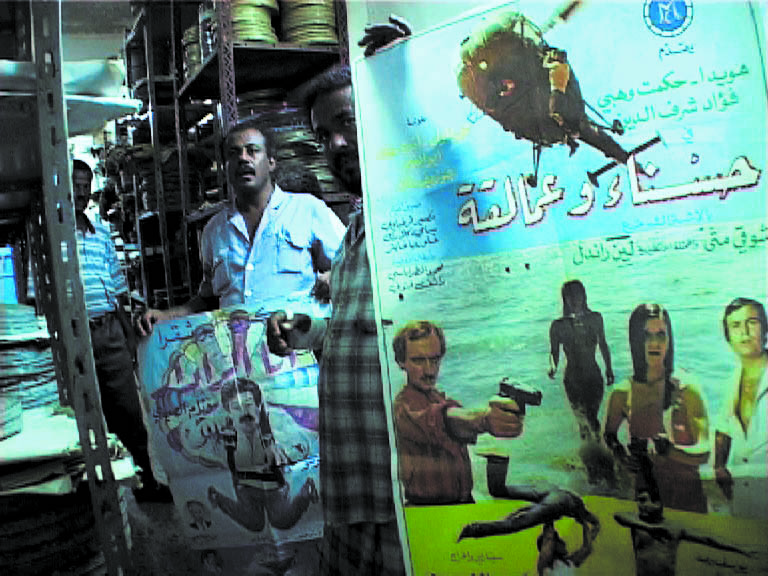

This project came into being at a moment when a wave of collective mobilizations erupted on the global political landscape. The year before had started off with the Arab Spring and had culminated in the Occupy Wall Street demonstration, shortly to be followed by protests in Bulgaria, Sweden, Turkey, Brazil and elsewhere, as well as manifestations of movements such as Los Indignados and Aganaktismenoi, to name but a few. In conjunction with this wave of insurgency and the growing concern with emancipatory thought and practice, more and more artists seemed to take upon themselves the responsibility to fill the void created by the consensual practices of governmental politics and attempt to invent new forms of intervention and participation. This so-called “political turn” could to some extent also be felt in the world of cinema, not only in a retrospective fascination for the past ventures of “militant cinema,” but also in the endeavours of numerous contemporary artists and filmmakers to give cinematic expression to the injustices and inequities perpetrated on a global and local scale, as well as the struggles aimed to defy them. In light of these invaluable efforts, Figures of Dissent could not pretend to offer anything but modest echo chambers which allowed for some of these efforts to find a multiplicity of resonances and dissonances, whether in the form of appearances or in the ring of words. The dozens of public showings and exchanges that were proposed did not profess to be able to directly participate in the much-needed organization of collective political dissent — they merely sought to bring about communal situations where time and attention could be paid to remote figures brimming on the surface of the screen.

How to make sense of these “figures”? Do they bespeak the represented characters and embodied emotions that invite immediate identification, or rather the mute shapes and flickering shadows that tend to resist identification? Do they denote the material presence of bodies and objects or the apparitions and operations that tend to diverge from this presence? The forms of life that appear in front of the camera lens or the forms of art that are produced by the filmmaker? And what about the “figure” of the artist as producer of aesthetic appearances, as author of the work carrying her or his signature? Oscillating between the personal and the impersonal, resemblance and dissemblance, the polysemy of the word “figures” seems to underscore some of the fundamental ambiguities and paradoxes that are inherent to the art of cinema, as well as the political promises and efficiencies that have been ascribed to it. Are political effects to be located within the cinematic work itself, in the intention of the filmmaker or rather in the subjectivity of the spectator? Can a film have a dissensual potential in and of itself or is it contingent on a broader disposition of sensible experiences? How to negotiate the relation between appearance and reality, between recognition and disruption? How could the mediation of cinematic appearances possibly make a difference in light of the immediacy of the real? Trying to come to terms with how these questions can be dealt with today cannot but lead to an inquiry into the ways in which they have been met in the past. That is why, from the outset of the Figures of Dissent project, it was clear that tackling the conundrum of cinema and politics required a deep plunge into the topographies of positions and arguments that have attempted to define the capacities and incapacities of cinema and those of its spectators for making sense and significance.

The writings that are assembled in this publication are a tentative outcome of this plunge. They have taken the form of five letters addressed to five people whom I have met in the context of the Figures of Dissent project. Each letter was written as an exploration of certain shared paths through the landscape where the territories and geographies of cinematic appearance intersect and collide with those of political actuality. The first letter, addressed to Evan Calder Williams, was written as an intuitive inquiry into some of the questions and confusions that had remained lingering in me after having organized The Fire Next Time conference, which was set up as a revisitation of the practices and theories of “militant” cinema, in particular those that were associated with the upheavals and movements that swept the world in the 1960s and ’70s. What were the conditions that made these particular modes of thought and action conceivable and effectual? What makes something thinkable in one era but inconceivable in another? These questions were refocused in a subsequent letter to Mohanad Yaqubi, in which I tried to figure out some of the changes in form and attitude that can be discerned in cinematic engagements with political struggle, in particular those that have been dedicated to the Palestinian struggle. Central to the investigation is a film that Mohanad and I had been discussing in the course of earlier encounters, a film that returns in several of the letters: Jean-Luc Godard and Anne-Marie Miéville’s Ici et Ailleurs. My writing to Barry Esson too was triggered by an impression that one particular film had made on me, an impression that caused me to rethink my work and role as a so-called “curator.” I saw this film, Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep, as part of one of the “Episodes” that Barry has been organizing with Arika, a Scotland-based political arts organization devoted to the cultivation of a collective practice of study. The letter was composed as an attempt to make sense of this experience while at the same time questioning expectations of what cinema can do and what we can do with cinema. I was inclined to engage with this challenge once more after meeting with Sarah Vanhee, who spoke to me of a “crisis of the spectator.” She was speaking from her experience as an artist who tries in her own way to create modest fissures and fractures in the texture of the sensible landscape by disputing widely held antinomies between art and non-art, activity and passivity, activating and spectating. I responded by coupling my own wrestling with these antinomies with my impression of a film I have been regularly showing in the past years, Handsworth Songs by the Black Audio Film Collective. A fifth letter was drawn up as a reaction to the perception of yet another “crisis,” which a friend has referred to as the “depression of fiction.” Why is it that the traditional forms of cinematic fiction seem to have trouble to give expression to the injustices that haunt our times and the struggles that aim to defy them? Which network of expectations, arguments and paradoxes underlies this perception? These questions, which enkindled a fragmented journey through the history of the meeting grounds of art, cinema and politics, were addressed to Ricardo Matos Cabo, whom I have been exchanging thoughts with ever since we met in the company of Pedro Costa, a filmmaker who takes up an important position within these writings. Finally, in May 2016, just before this manuscript was supposed to go to the printer, I decided to add a sixth letter in which I followed up my correspondence with Barry Esson with a general reflection on the Figures of Dissent project. The issue in particular that elicited this addendum was a demand addressed to me which has for some time taken me aback: a demand to clarify my position as “spectator” or “producer.”

Some of these letters, which are published here in chronological order of writing, found their motivation in the experience of specific film works, others tried to work their way through an entanglement of discursive strings. Some set out to untangle particular knots that bind the forms of a cinema of politics with the outlines of a politics of cinema, others zeroed in on the challenges and ventures of curatorship or spectatorship. Some might have a more intimate and even emotive ring to them than others. But all of these letters have in their own way sought to give resonance and continuance to unfinished conversations and dangling thoughts, without any certainty of outcome or response. Far from being the result of well-planned journeys, these writings have unfurled as aleatory trajectories that join a variety of impressions, associations, derivations, convulsions and digressions. Rather than the accomplishments of a determined search for certainties, they remain speculative forms of study that stem from the wanderings of a bricoleur who has attempted to put things into play and construct a meaningful meshwork of thoughts and half-thoughts, interpretations and misinterpretations. Their zigzagging and meandering motions, with no appropriate destinations in sight, bear witness to the development of an erratic learning curve, one that has by no means reached a finality. Like the many encounters that have been made possible over the past years, the writings that have accompanied them are but provisional explorations of an inexhaustible question which provides for a multitude of departures, junctions and disjunctions. Like messages in a bottle launched into the vast expanse of possibilities, they are merely waiting to be furthered.