In the context of the Courtisane Festival 2016 (23-27 March).

“I believe people accept there is no real alternative.” Thus spoke the Iron Lady. After the freezing Winter of Discontent came the long-awaited ‘winter of common sense’. An era is drawing to a close, she claimed, meaning that the time for foolish dreams and misguided actions was over. There were to be no more diversions from the one and only course worth pursuing: that leading to the triumph of global capitalism and liberal democracy. While those in power started to pursue vigorous reform programs of neoliberal economic policy and regressive social agendas, some of those who lost their bearings blamed the ‘bloody-minded’ commoners for having invited the ravages brought upon the dreams of another future. As the memories of struggle faded, counter-forces retreated to a defensive position, where they could merely see fit to protect the freedoms and entitlements that had been acquired with so much grit.

“Wanting to believe has taken over from believing,” a filmmaker observed. But the uncertainty did not stop filmmakers from making films, just as it didn’t stop movements from occupying the spaces that the traditional counter-forces had excluded and abandoned. Instead of holding on to the plots of historical necessity and the lures of an imagined unity, they chose to explore twilight worlds between multiple temporalities and realms of experience, situated in the wrinkles that join and disjoin past futures and future presents, memories of struggle and struggles for memory.

This program presents a selection of British films that have documented and reflected on the changing political landscape in a period that stretched from the mid-1970s to the beginning of the 1990s. At its core is the work of a filmmaker who was pivotal within Britain’s independent film community: Marc Karlin (1943-1999). He was a member of Cinema Action, one of the founders of the Berwick Street Film Collective, director of Lusia Films, and a creative force behind the group that published the film magazine Vertigo. Described by some as ‘Britain’s Chris Marker’(with whom he was befriended), he filmed his way through three decades of sea change, wrestling with the challenges of Thatcherism, the demise of industrial manufacturing, the diffusion of media and memory, the crisis of the Left and the extinguishing of revolutionary hopes.

The work by Marc Karlin and the other filmmakers in this program allows us to feel the pulse of an era of transition, whose challenges and transformations are still with us today. At the same time that the Iron Lady is being immortalized as ‘a force of nature’, while the arguments for the austerity policies that she championed are crumbling before our eyes, a time when the present is declared to be the only possible horizon, it may be worth our while to revisit this era, if only to discover that history is not past – only its telling.

In the framework of the research project “Figures of Dissent” (KASK/Hogent).

Special thanks to Andy Robson and Federico Rossin

———————————————————————————————–

THURSDAY, MARCH 24, 2016 – 12:30 – KASKCINEMA

Nightcleaners

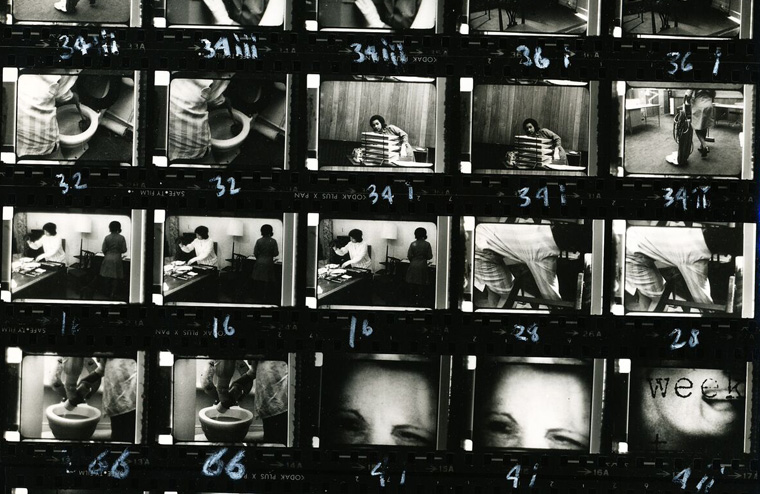

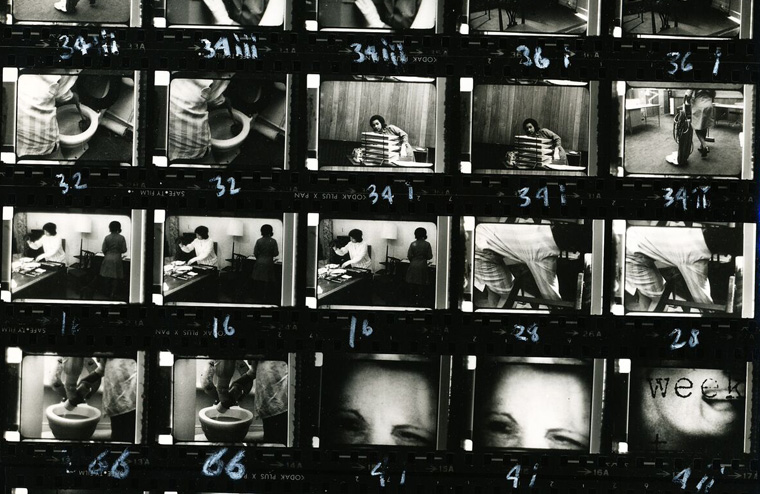

Berwick Street Film Collective, UK, 1975, 16mm, video, 90′

Nightcleaners was originally conceived by members of the Berwick Street Film Collective as a campaignfilm about attempts to unionize women working at night as contract cleaners in large office blocks. But in the process of making the film, it became, as Marc Karlin observed, a film “about distances”.

“The film was about the distance between us and the nightcleaners, between the women’s movement and the nightcleaners, and was choreographing a situation in which communication was absolutely near enough impossible. I mean, there were these women who were in the offices at night who would wave, or sign or whatever, and sometimes we had to get into offices through very, very subterfuge-like means. The women’s movement came mainly from a kind of middle-class background, and I got in terrible trouble for even saying there were distances, or making a film about distances, and that is what I wanted to do, by and large… The nightcleaners haven’t changed, and it always comes back to this idea, you know, of W.H. Auden and all those people who say: “Well, you know, a poem won’t stop a tank.” Maybe not, but a poem can actually reveal a tank and… I think with Nightcleaners what we did was we revealed the situation of the nightcleaners on the one hand and on the other, the impossibility of capturing those lives.” (Marc Karlin)

———————————————————————————————–

THURSDAY, MARCH 24, 2016 – 22:30 – SPHINX

‘36 to ‘77

Marc Karlin, Jon Sanders, James Scott, Humphrey Trevelyan, UK, 1978, 16mm, video, 85′

Nightcleaners was originally conceived as the first of an ongoing series. Material subsequently shot for Part 2 eventually became ‘36 to ‘77, in which Myrtle Wardally, one of the cleaners in the earlier film, reflects on the strike and on her life, then and afterwards.

“To me ‘36 to ’77 is very important for the way it changes the understanding of how you live with representations. The normal film or television experience leaves you without any trace. It doesn’t hurt you at all to look at it. With ‘36 to ‘77 I realised how people desperately desire a certain normality for film. It’s such an obsessive need, and when for instance political people see the idea of rendering their politics visible, it completely breaks them apart. A film does test how real your politics are, to the extent of confronting you with something that breaks the very boundaries in your writing. Film acts as a sort of dislocating lever. There’s a lot of left rhetoric about personal politics which is actually a refusal to take personal politics seriously – it’s a refusal to dismember yourself, to re-think, re-phrase, re-constitute yourself in the light of your actions and the things in front of you. It’s a refusal to see age, to see change, to see distances, always taking the same photograph of yourself, wherever you are…The representation of workers on film is normalised because it’s always surrounded by and held in the situating of them as workers in a recognisable political situation, and which a lot of people might not be sharing. The idea that they might have other things that would contradict your idea of them never obviously comes into play now.” (Marc Karlin)

———————————————————————————————–

FRIDAY, MARCH 25, 2016 – 13:00 – KASKCINEMA

For Memory

Marc Karlin, UK, 1982, 16mm, video, 104′

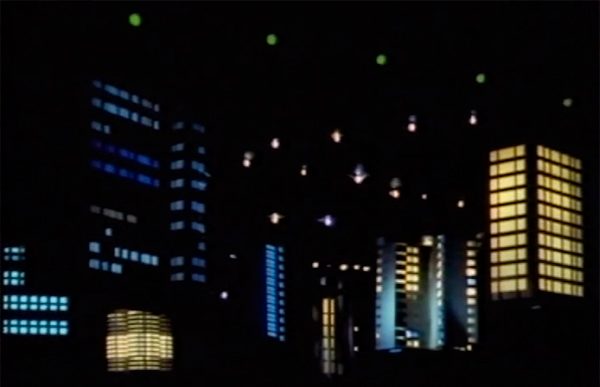

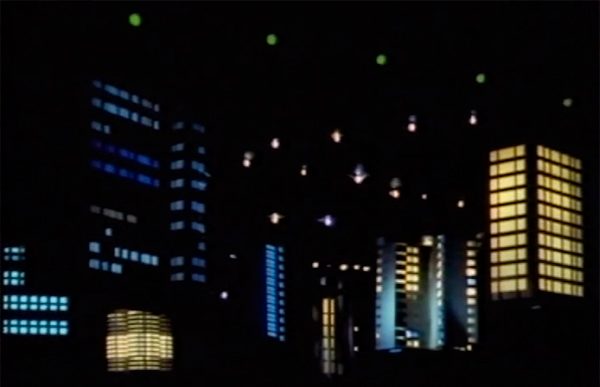

Produced between 1977 and 1982, this film remained on the shelves until the BBC finally broadcast it in a sleepy afternoon slot in March of 1986. For Memory is a contemplation on cultural amnesia, written as a reaction to Hollywood’s Holocaust film, a serialisation of the genocide. Karlin asks: how could a documentary image die so soon and be taken over by a fiction? Seeing that an enormous amount of documentation exists, why did it take a soap opera to have the effect that it did?

“The film came out of a showing of a Hollywood series on the Holocaust. I was deeply shocked by it because of its vulgarity and stupidity… And yet, and yet…! In a sort of Auden-tank sense, it had an enormous effect! In Germany, for instance, where children saw it and were given history books or packages to do with the camps, and so on. I was really disturbed that something like this Hollywood series established some kind of truth, and I just wondered where another kind of truth had disappeared, which was that of the documents. The documents had died to the point where, much later on, in Shoah, Claude Lanzmann would not use a single document. So, I was interested in kind of pursuing them. That led me to think out how, in the future, an imaginary city would remember – because it was the very convenient thing to say that modern times are totally to do with amnesia.” (MK)

———————————————————————————————–

FRIDAY, MARCH 25, 2016 – 15:30 – KASKCINEMA

So That You Can Live (For Shirley)

Cinema Action, UK, 1981, 16mm, video, 83′

So That You Can Live developed from a project called The Social Contract, which the Cinema Action collective began in the mid-1970s. When filming in Treforest, South Wales, the filmmakers met Shirley Butts, a union convenor who was leading a strike by women demanding equal pay. In the subsequent five years, they documented the impact that global economic changes had on her and her family. As Marc Karlin remarked, So That You Can Live is “a film of and in transit – from city to countryside, from employment to the dole, from generation to generation, from power to powerlessness”.

“The most important British independent film since Berwick Street Film Collective’s Nightcleaners, Cinema Action’s So That You Can Live (For Shirley) is in many ways a very simple film, about a family in a South Wales valley community which has been struck down in the last five years – the period over which the film was made – by the socially destructive consequences of pit and factory closures and the resulting unemployment… Slow and beautifully controlled, a poetry unfolds in this film of enormous depth of feeling and lucid intelligence, and in this way it becomes a passionate plea for the voice of conscience to be heard again in the labour movement. For the word and the idea to become once again part of our vocabulary, as it was for previous generations. For us all to look around and see, in the shapes and forms of our environment, what parents and grandparents tell to those who ask of what is only recently past, the history of Living memory.” (Michael Chanan)

———————————————————————————————–

FRIDAY, MARCH 25, 2016 – 17:00 – KASKCINEMA

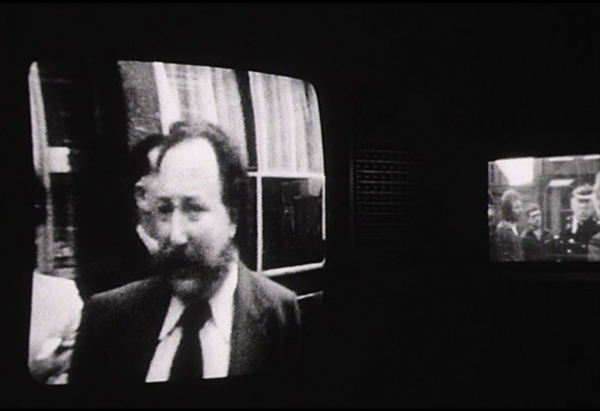

The Year of the Beaver

Poster-Film Collective, UK, 1985, 16mm, video, 78′

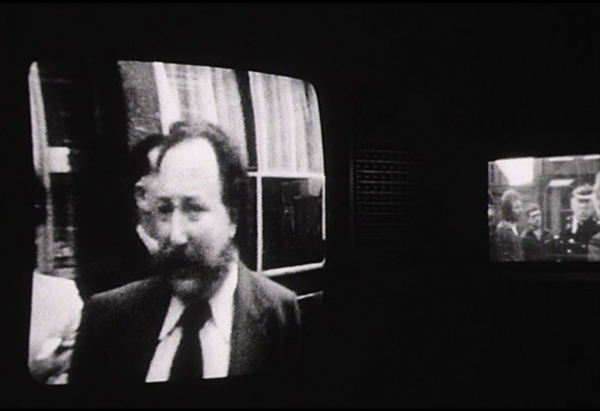

The Year of the Beaver documents the strike at the Grunwick film processing factory in North London in 1976-‘78, which was then described as “a central battleground between the classes and between the parties”. The film, which incorporates a lot of the material from the reporting that was being produced at the time, is not only a documentary of a strike, but a portrait of an historical period, as it underwent transition to the modern ‘civilized’ state under Thatcherism.

“It wasn’t until the early eighties that a film called The Year of the Beaver emerged and I first really met Marc Karlin as he hugged me on seeing it. A film which had, for all the efforts of the inexperienced people who had worked on it, managed to create layers of meaning and make connections between the myriad of things it had had to take on board. It showed what had come to be viewed as the seeds of Thatcherism developing long before her reign. This mammoth work had been years in the making, years in editing rooms struggling for ways and means to illuminate a story that needed to be told, to find an adequate form in which to tell its tale.” (Steve Sprung)

Followed by a DISSENT! talk with Ann Guedes (Cinema Action) and Steve Sprung (Cinema Action, Poster Collective).

———————————————————————————————–

SATURDAY, MARCH 26, 2016 – 13:00 – PADDENHOEK

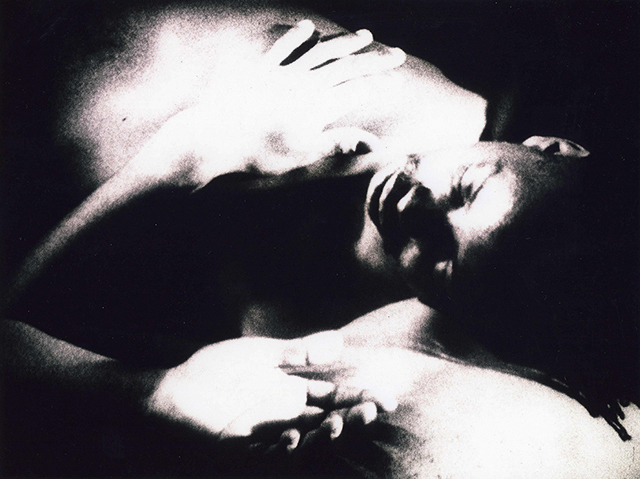

Nicaragua: Voyages

Marc Karlin, UK, 1985, 16mm, video, 42′

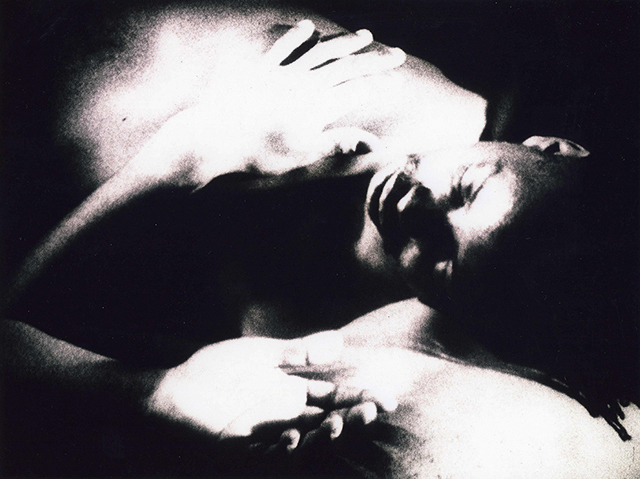

The first film in Marc Karlin’s four-part series on the Nicaraguan revolution that brought down President Somoza’s regime in 1979, Voyages is composed of five tracking shots, gliding over blown-up photographs that Susan Meiselas took during the insurrection. The film takes the form of an imagined correspondence, which interrogates the responsibilities of the war photographer, the line between observer and participant, and the political significance of the photographic image.

“Photographs are in a way far ahead of our ability to deal with them – we have not yet found a way of dealing, living with them. We have appropriated them in a channel – ‘language’, ‘papers’, ‘magazines’, ‘books’ – all of which seem the only tools by which we can give them an earthbound gravity. We brush past them, flick them, demand of them things they cannot give… Liberate photographs from its priests and jujumen – including myself. We do not need interpreters. We need looks – and thus the task is up to the photographer to renew his or her contract i.e. what can photographs and their arrangement do to defy the prison house interpretation à la John Berger – and make us think of ourselves in relationship to Nicaragua.” (MK)

Twilight City

Black Audio Film Collective / Reece Auguiste, UK, 1989, 16mm, 52′

“A love story about the city and its undesirables,” this third film by the Black Audio Film Collective evokes the New London – in the filmmakers’ words “a fading world of being and unbelonging, invisible communities, the displaced and the rise of redevelopment.”

“The film presents an imaginary epistolary narration of a young woman’s thoughts as she writes to her mother in Domenica about the changing face of London, then in the throes of the new Docklands development. She fears it is a city that her mother would not now recognise should she return. The film cuts between this narrative voice and interviewees bearing witness to their youthful experience of the city as a territory mapped by racial, cultural, sexual, gender and class boundaries, a place ‘of people existing in close proximity yet living in different worlds.’ This polyvocal narrative moves restlessly back between past and present, reflecting on the loss of roots and erasure of history caused by the demolition of old established neighbourhoods. The further displacement of already marginalised communities falls under the shadow of the films’s recurrent motif of the public monument to a heroic British imperial history notable for its effacement of its disruptive descendants.” (Jean Fisher)

———————————————————————————————–

SUNDAY, MARCH 27, 2016 – 17:00 – PADDENHOEK

Scenes for a Revolution

Marc Karlin, UK, 1991, 16mm, video, 110′

Revisiting material of his earlier four-part series, Marc Karlin returns to Nicaragua to examine the history of the Sandinista government, to consider its achievements and assess the prospects for democracy following its defeat in the 1990 general election.

“For ten years, the Sandinistas had tried to make democracy mean access to education, health, nationhood, and the sense of collective responsibility. Now in one swift move Nicaragua found itself suddenly transplanted to the political events of Eastern Europe. It was as if differences, identities, separate histories, could all be electronically and democratically jammed. But then in this day and age, anyone and everyone could speak the word ‘democracy’. What it meant, what it felt like, what it could be as opposed to what it was not no-one would dare say. As if a democracy to really work had to be by definition valueless, orderless, heard but not seen. As if democracy could be about nothing else but the right to be left alone… For ten years Nicaragua had hardly been out of the headlines. Now that it was officially declared a democratic nation it was hardly ever heard of. As if democracy instead of making voices heard was there to silence them. A confirmation after all that history and all its wrongdoings had officially ended. But these images, so often seen in films on the Third World, to the point of invisibility, were the product of a bitter poverty which had not been erased. If in 1983 we had come to film a socialism that had hopefully learned from its past mistakes, in May 1990 we were still filming the reasons why that dream would simply not go away.” (MK)