Transcript of a short Q&A with Pedro Costa, after a screening of Juventude em Marcha (2006) during the courtisane festival 2015.

After having just seen Juventude em marcha again, and Casa de Lava yesterday, I couldn’t help noticing quite a few resonances between the films: for example, the reference to the title, the card playing, the letter, … As if there’s some kind of continuous movement of rediscovery, re-imagination, reinvention. Do you consider your films as part of an ongoing work of progress?

More or less. It’s doing something in cinema that I can’t do in life, which is to continue side by side with the same people, loving and caring for them. It’s very simple. It’s being very afraid of people dying and going away… I like being in the same places, in the same spaces. Doing the same work. That’s why things seem to have this continuity or this permanence. The filmmakers that I like also have their own small part of the world. You’re there, you stay there and you remain more or less faithful to that.

Like John Ford going back to Monumental Valley?

A little bit. There’s always a difference between life and cinema. But it’s a conversation, an attempt to balance something. In cinema I think I can balance better than in life.

I remember Daniéle Huillet once saying that the most important aspect of filmmaking is the collective work. Earlier you mentioned that you have no convictions, at least not the kind of convictions that filmmakers like Straub and Huillet have. Is this collectivity, this search for a kind of solidarity something that keeps you going?

It’s one of the things, yes. I had this panic moment in my “professional” life, let’s say. There was a moment when I said: “I don’t like what I’m doing, I don’t like the way it’s done”. I didn’t even like to go to see films, except for the Fords and the Ozus. It was boring. So I said: “something has to change”. So something changed. But it was a very frightening moment. Then I discovered things – or perhaps they were just mysteriously there: a certain place and people and words and colors … They were there and I thought: “perhaps these are the things that I’m here for”. That was twenty years ago or more, and it’s still new every day. My ideas for making films depend on that place. Now it’s not even a place anymore, it’s an imaginary place, because that particular place does not exist anymore. What you see in Juventude em marcha is the moment when the change happened, between the old place and the new place, the transformation to new rules and new lives. But it’s still there, the community is still resisting a little bit. This solidarity between us still exists. Making these films depends on a lot of things that are not the usual spices of filmmaking. Of course it’s money, machines, camera, energy, desire. But then it’s also a lot of different things that I wouldn’t like to tell you about, because it seems very abstract and sentimental. You don’t have to know about that.

Is it still frightening for you? Is the fear still there?

Yes, for everybody. Because it’s very connected to something which is essential. It’s the core or heart of cinema: what’s next? It’s very frightening. It’s always there when you’re involved in making films: what is the next shot, what comes after this? Well, Hitchcock knew about all of that.

Where does the desire for making a new film stem from? If I’m not mistaken Juventude em marcha started with a memory of Ventura.

This came more from me, I think. The making of the film before, No Quarto da Vanda, was very traumatic. It was about a lot of young people, people in very problematic situations: there were drugs, suicidal cases, it was very tough. Some of them never saw the film. Even Vanda held a very critical distance, even though she is, I could say, the co-director of the film – she did almost as much of directing as I did. So after this film, after working with people of more or less my age I thought I would like to see different ages, I would like to see how it started, that place I thought I knew then. So I wanted to do some kind of historiography or anthropology. It still is a bit sociological. I really like sociological films. I really do. Like Thom’s (Andersen) films for instance. Remember: sociology used to have a good name – like shoemakers. I’m fed up with philosophy in cinema, I prefer sociology or anthropology. For me, Ventura was a kind of detective or historian, going around collecting memories and stories. This mysterious, more abstract moment in this shack with his partner, for me, is the past, the beginning of the present.

There seems to be a tension between two approaches, two modes of consideration: on one hand there is what you call “anthropology” or what others might call the “documentation” aspect – chronicling the lives of the people you work with. But on the other hand the films also has this epic, mythological side, something that’s even more present in your new film, Cavalo Dinheiro. Is that what you meant when you earlier talked about the struggle with realism?

I think you can say that of other filmmakers work too. Probably it comes from Straub. But it also comes from filmmakers before Straub, this epic tradition – it’s not even a tradition, it’s an affection. You cannot but try to treat these people with the best lens you can get. I have a very shitty machine, but my lenses I think are ok. They have to be seen like they’ve never been seen before. It’s a bit of a cliché but they have to be bigger than their lives, the lives as they are represented in the papers or on tv. It has to be something else. And it was something else with Brecht, Ford, Straub, Godard, Bunuel, poetry too – the letters in this film come from the French poet Robert Desnos – all these guys… From some it comes visually more obvious, for others it comes from another aspect of their work. For instance this film is really between an odyssey, an epical voyage, and what in music or poetry you can call an elegy. An elegy you sometimes do for past, dead friends, or lovers, people you admire.

You were just talking about the need to search for new approaches, for “something else”. Does this get harder within the limitations that you have set for yourself or do you have the impression that you are getting closer to some kind of “secret”?

There’s no secret. There’s fear, being afraid of what’s next, of what comes up, of what tomorrow will bring. But there’s really no secret. You only get older, your body gets weaker, your mind gets a little bit less clear… In cinema it’s very simple: you get used to something and if you’re serious you get more aware of certain details, like in painting. I’ve always liked routine. Every time I have my camera with someone, It’s like it always used to be, and that’s very reassuring for me. That’s why I changed production mode, let’s say. I hated the variety, the novelty, the newer and the bigger – that kind of ideology and mythology of difference-making. It’s very present in filmmaking today, but I don’t care for it. For me it’s the same old thing, the same old shot, the same old work. Even the people I work with never change. I would like it to be like that forever. But we have to change sometimes and I think it’s bad – I made a film called “Don’t Change”, so…

What do the films mean for the people you work with? Is it just work for them? What happens when you show the films?

Their relation to cinema is different than mine. They work and they act in the films, but it stops there. I don’t believe in this mythology of how cinema can change their lives or how making films is good for them. Perhaps it is a little bit – though not on the financial side, because they get very little money, like myself… But I have always worked with people who are more on the unemployment or retirement side, people who are there, just there. That’s also important because they are people who have a distance, have a way of thinking about or looking at things, like Vanda, Ventura or now Vitalina. They have this, I almost could say “unemployed” look at things. Vitalina is terrible and terrifying but that’s very useful for me, because it’s critical, powerful. There’s a tension, a certain kind of dramatic tension that I could perhaps not get from actors, something that you cannot fake. I’m not only interested in artistic qualities or the tensions that you can see – the eyes, the hands, the words – but I’m interested in the truth of that, doing that kind of work. If you’re a serious filmmaker, artist or teacher you are or should be naturally interested in the question of how we can make things better, how can we solve problems, asking ourselves “what happened? Why is it so bad, so difficult between us, so dark and cold?” There are no good films but these ones. But it’s becoming more difficult – I created my own prison, that’s the problem now. I still believe I have my freedom in this way, but it’s also a prison, a very confined space. I’m more and more making the films with leftovers. Well, it used to be leftovers, like In Vanda’s Room. When I say leftovers, I mean I didn’t have any money to make the film, I made it with the most awful camera in the world – I mean, she’s my adored friend, I owe everything to her, but you can buy it in the Media market. I mean it’s not what cinema wanted. I did In Vanda’s Room with cigarettes and change. Vanda used to say something every day that made me cry. She used to say: “I could have been a girl”. That’s unbearable. So the film was made with those ruins. Now there are not even ruins left. I’m making the films with what they allow me to make the films with. Which is also very good because it reduces my small space even more and that makes me think: how can I solve this dramatic problem, visual, sound, … ? But every filmmaker has his or her own kind of method or working, of moving forward or backward.

I remember you saying that you would like to work more with the younger generations in that neighborhood. Has that proved to be more difficult?

You don’t see them in the films, but they help me. I don’t know what the future will bring. By chance I was drawn to Ventura and then to other people, to this memory lane. Now I’m stuck in this thing, because I don’t have anything else. I don’t have the money or even the desire to do much more than watch people remember. We’ll probably move closer to theater, or to some form of theater.

Or musical, like Horse Money?

Yes, or between both. With music and theater you’re safe, you’re home free. The problem is that cinema refuses a little bit the word and music. I’m not Godard or Ozu or Ford to make those kinds of things. Somebody up there talking or singing or just the music pouring out of there, you don’t do it just like that. It’s very difficult, hard work.

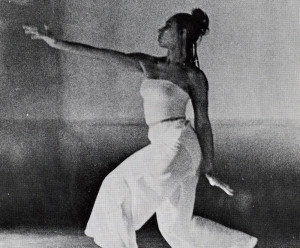

(Then, one of my most beautiful memories of the festival: a young girl comes all the way down from the last row of seats to tell Pedro she loves the way the people in his films move, stand, gesture and touch one another. She asks “I wonder how consciously do you ask them to do this?” Thank you Manon.)

It’s not like there’s only one way. Each person is very different. Because they are not actors, there’s something that they can give me and you and cinema that actors can perhaps not. Mind you: I’m not against working with actors: there are very good ones, I love some. But these people, they give some very small – or large – mainly priceless things that you cannot pay for, cannot dream up. Each one of them has their own singular movement. In Colossal Youth, There’s this scene with Ventura playing a record, while the other guy is drawing or doing something on the table. I thought that scene should have been shorter than it is. Now it sways very slowly with the music and that’s because Ventura felt like doing it like that. It’s not a question of direction or organization. I remember I said that the scene was too long. Sometimes, you get afraid and you don’t really realize what you’re doing. Because I have a lot of things to take care of, lots of things I’m worried about, so many things escape me. Sometimes you think “this is going on forever”, so you try to speed it up. I could never with him. It’s just his tempo, his way of moving, of expressing himself. Vanda is completely different. You can see that. What’s interesting is the shock, the confrontation between them, it’s like movements that collide. When Ventura and Vanda are both on the bed, it’s amazing because she’s always very stressed, nervous, paranoid and he always seems very calm. But I know that he was much more tense than she was. He was really nervous about everything, about her, her state of mind and condition. This is interesting with people who are not actors. With actors it tends to be predictable, here it’s in constant motion – from the first to the second take, everything can change, the position, the speed… if they want to. I’m not the director of everything: moving a finger is something I cannot dream of, something I don’t want to imagine. Those things are always very surprising.

Do you discover these little things while editing? I know you never liked to watch rushes.

Today there’s no more rushes, we have camera’s that have their own lcd screen. I see it immediately, everyone does. In Vanda’s room usually there was Vanda and her sister or someone else, and when somebody got off-screen, they came to sit next to me to see what was happening with the one that stayed. Normally they were joking, making faces… – very “cinema”. They are not actors. Perhaps they are a bit more naïve. Well, not naïve, but more direct. There’s no intellectualization, it’s simple action-reaction and taking care of a kind of movement and – if words are involved – a text. But what I like is the constant surprise of this kind of work. It seems very controlled but it’s really very evolvative – it changes all the time. If you would see the rushes, you would see that the takes are very different. It’s like Chaplin’s method of rehearsing on camera: doing exactly the same thing five hundred times. Then you see the finger or the wrist moving. But there are a lot of things that I cannot explain to you: actors, shots, technical stuff. We can never talk about that in Q&A’s. We can watch the film shot by shot and then it’s a bit more serious, like I did with the film with the Straubs. I always end up saying banalities, more or less.

Audience member: What is your relationship towards the audience? What are you hoping to convey to the spectator?

Lately I’ve been having these weird dreams, thinking “oh, they probably won’t understand”. It’s very recent. For the last film I thought “they probably won’t understand this connection or this jump”. “They” meaning “you”. Because I myself was not understanding certain things I did. Why should I understand everything? Or make it understandable? I don’t mean that I want to make pure poetry or abstract painting or pure philosophy in motion. I still believe that the best movies are the ones that narrate, which is not the same as telling a story. There is something called narration, and that for me is fundamental, it’s crucial. If it’s not there, I give up, I abandon things. But I have a feeling of what it is because I come from the study of history. It’s almost organic, genetic for me. I know that everything is narration, everything. It’s like a huge, immense, subterranean flow. It’s everywhere, but it’s very difficult to control, to organize and to construct. And in film it’s even more difficult than in a novel, especially after so many great narration masters like Griffith, Ozu, Ford, Godard, Straub, Rosselini. There are so many of them that changed things. And the world being what it is today, which has never been as bad… This is the worst moment, I think. Not just because we’re living it. For film it is for sure: just think about the digital ideology. It’s not only about the story: shooting with the cameras I’m using, I need twelve times more time than I used to with 35mm. Because even the camera is designed to do something else. It’s a camera that for instance does not allow shadow. Everyone knows this. Perhaps I exaggerate in shadows, because I like them. But these digital cameras do not believe in shadows, they don’t think about them. So I’m trying to remember, remember shadows.

Yesterday I don’t know if you were here to see Farrebique. I mean, it’s two hours of science fiction. It’s just doors and dogs and people walking. Like you’ve never seen those things before. It has been years since you have seen a baby cry in a film. So that’s also one of the tasks of the filmmaker today, I think: to remind people that a door shuts with a sound and people go through the door and come from the door and not only fly through walls. And that people are kind and don’t kill five hundred guys per second. This is just a cliché, but there’s much more: like the shadows…

I’m very fond of a Korean filmmaker called Hong Sang-Soo. I think he’s doing a magnificent job. He’s a guy who’s working in a field that is much needed: small sentimental comedies. Films that, I think, are much better than Woody Allen’s. Woody Allen used to be good, he’s weaker now… Hong Sang-Soo is the guy who took over an I think cinema needed that, needs that. He does it in a, for me, very wonderful way. He’s reminding people: do you remember these kind of situations between people, how we used to feel watching this kind of things. There’s also the Chinese Wang Bing doing his work and showing some other things. Which is also about reminding people: don’t let certain things happen or watch this closely. If you see something like this, watch out. It’s about warning sometimes. So I’m saying “sociology”, “warning”, “message”. I’m doing the complete no-no Q&A. But I do like sociological films with messages.

Talk with Stoffel Debuysere. Thanks to Lennert for recording, Ruben for the transcript, Manon and Frederik for the questions.