Jean-Luc Godard in conversation with Jacques Bontemps, Jean-Louis Comolli, Michel Delahaye, Jean Narboni

Originally published as “Lutter sur deux fronts” in Cahiers du Cinéma, no. 194 (October 1967). English version published in Film Quarterly, Vol. 21, No. 2. (Winter, 1968 – Winter, 1969). For some context and insight, read Jacques Rancière’s essay ‘The Red of La Chinoise‘.

“What we demand is the unity of politics and art, the unity of content and form, the unity of revolutionary political content and the highest possible perfection of artistic form. Works of art which lack artistic quality have no force, however progressive they are politically. Therefore, we oppose both works of art with a wrong political viewpoint and the tendency toward the “posters and slogan style” which is correct in political viewpoint but lacking in artistic power. On questions of literature and art we must carry on a struggle on two fronts.”

-‘Talks at the Yenan Forum on Literature and Art’ (May 1942), Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-tung, Peking, Foreign Language Press, 1966, p. 302.

Because of the kind and the degree of its commitment, people are wondering whether La Chinoise doesn’t risk losing adherents to all the political “lines,” and whether it doesn’t, then, in the final analysis, just bring it all back down to film.

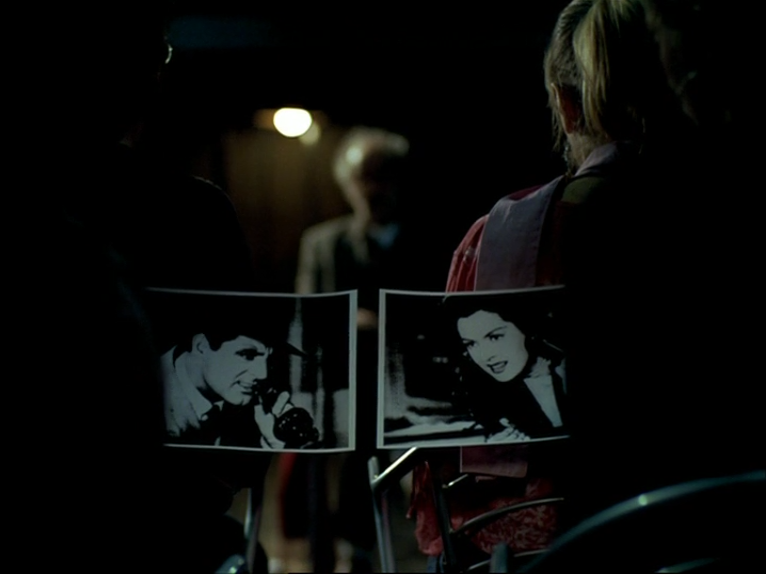

If that were the case, it would have missed its mark and be reactionary. What you say reminds me of what Phillipe Sollers told me about it. Though he, unlike the people you speak of, bases his view of it on the idea that it doesn’t as a matter of fact “bring it all down to film.” To give support to his view, he points to the conversation between Anne Wiazemsky and Francis Jeanson on the train. According to Sollers, the scene is reactionary. It’s reactionary because it pits the “real” talk of a real person – the talk has to be “real,” he says, because the character’s name, like the real man’s, is “Jeanson” – against the “fictional” speech of a pseudo revolutionary, and because the scene seems to justify the former.

Do you think it does?

I think it justifies Anne Wiazemsky’s position. But spectators side with whichever they choose.

Why did you ask Francis Jeanson to be in the movie?

Because I knew him. So did Anne Wiazemsky. She’d studied philosophy with him. That meant they’d be able to talk. Anyway, Jeanson’s the kind of man who really likes talking to people. He’d even talk to a wall. He has the kind of humanity Pasolini defined when he said, in the movie Fieschi made about him for television, he didn’t like talking to dogs in the familiar terms you’re supposed to use. In any event, I needed him, Francis Jeanson, not someone else, for a TECHNICAL reason: the man Anne talked to would have to be a man who understood her, who’d be able to fit his speech to hers; it would be just that much harder when Anne’s text, if you can call it a “text,” wasn’t her own: I whispered it to her. I’d tried to find phrases that didn’t sound too much like slogans. But they’d still need to be linked. So I had to have a man with Jeanson’s skill. As it was, and although he was replying to really disjointed remarks, he always found the right answers; it looks like a coherent conversation, now. I was really relying on the allusion to Algeria. It places him well. It outraged Sollers. Others just say Jeanson’s an ass, and leave it at that. It’s a mistake, if only because he agreed to play a role. Others refuse – Sollers is one; I asked him to be in my next movie; so is Barthes; I’d asked him to appear in Alphaville. They were afraid they’d look like fools. That isn’t the issue. Francis has the sense to know that an image isn’t anything but an image. All I ask people to do is listen. Start by listening. I was afraid I’d hear people say what they said when they saw Brice Parain in Vivre sa Vie, that “they wished that old shit would shut up,” or even that I’d meant to make him look a fool. Because of the allusion to Algeria, they can’t. When I interview someone, independently of the personal reasons I have for preferring one man to another, the position I take is imposed by technique. Because he’d taught Anne philosophy, I thought at first that I’d film a lesson in philosophy – a mind giving birth to an idea, prompted by Spinoza or Husserl. But it became in the end what you see in the movie now: the idea being that Anne would reveal to him plans of action he’d try to dissuade her from, but that she’d go ahead with it anyway. To know whether that all exists only in fiction is another question; it’s hard to say; when you see your own photo, do you say you’re a fiction? To have an interesting debate on this whole thing you’d have to have Cervoni, say, for the one side and somebody from the Cahiers Marxistes-Leninistes for the other. Or Regis Bergeron and René Andrieu. They’d cover each other with shit for a start; but they might, still, come up with something in the end; but only if they’d agreed to start with film before they finally get into it.

The reaction from the Marxist-Leninists wasn’t the one you’d expected.

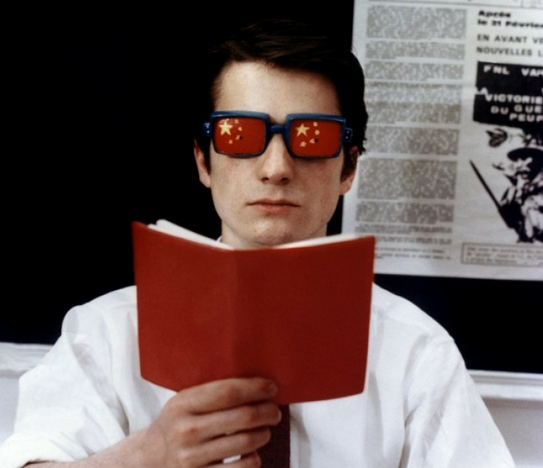

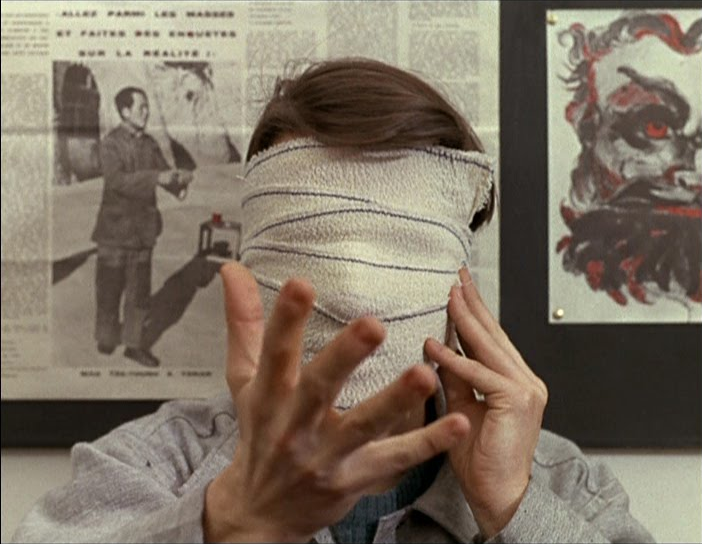

No, it wasn’t. They didn’t know what to think at the Chinese Embassy. They were really put out. Their big complaint was that Léaud isn’t all bloody when he unwraps the bandages. They obviously haven’t understood. That doesn’t mean, of course, that they’re wrong; but, if they’re right, they’re right at the first remove and not the second, or vice-versa. They were afraid, too, the Soviets might take advantage of Henri (a character who for a good many is far more convincing than I ever thought he’d be) to justify their own position. They weren’t too far off the mark: André Gorz (Henri reads some passages from his book Socialisme difficile in the first shot) was telling me it was “the first time he’d really liked one of my movies; it was clear, coherent; the concrete triumphs over the abstract, et cetera.” I guess I didn’t make it clear enough that the characters aren’t members of a real Marxist-Leninist cell. They ought to have been Red Guards. I’d have avoided certain ambiguities. The real activists – the kids who publish the Cahiers Marxistes-Leninistes; they impress you with their real, deep commitment – maybe wouldn’t have been as annoyed by it as they were. Because they shouldn’t have been. It’s a superficial reaction, I think, not too far different, when you get down to it, from the kind of reaction it got from the collaborators on Le Figaro: “It’s ridiculous! They say they want to make a revolution. Look where they’re going to make it – in a plush bourgeois flat.” Though this is said in the movie itself, quite clearly.

Can you explain this sort of misunderstanding?

People still don’t know how to hear and see a movie. That’s what we need to be working on now. For one thing, the people who have training in politics hardly ever are trained in film too, and vice versa. My training in politics came out of my work in film; I think it’s almost the first time that ever happened. Even if you think of a man like Louis Daquin, you realize all he’s doing is coming to film with an education he’s gotten elsewhere; a poor one at that. As a result, the movies he makes are just fair; they aren’t the good ones he might have made. All right, what can I say for my movie from this point of view? I can say I think it quite clear that it views the two girls with sympathy-with something like tenderness even; that it’s they who form the support for a certain political line; and, finally, that you have to start with these bvo girls if you’re going to understand its conclusion. It’s anyway Chou En-lai’s. They haven’t made a Great Leap Forward. The Cultural Revolution is only the first step in another Long March ten thousand times longer than the first. If you now apply this conclusion to the personal cases, the character played by Anne Wiazemsky, prepared as she is for it, is bound to go farther. So is the character played by Juliet Berto. Léaud really goes a long way: he finds the right kind of theater. Henri makes a choice; he decides for the status quo; he sides with the French Communist Party; he’s at a standstill, somewhere inside himself – the fixed-frame shot, the absence of cutting inside the shot characterizes this. As I view it, then, he’s cut himself off from all the real problems – but, I repeat, only if in judging a movie you start with a filmic analysis – it can be a “scientifically” or a “poetically” filmic analysis, but it’s got to be a filmic analysis – and not the fictional or the political plot. Krilov is the only one who really fails. This is all quite clear. Anyhow, it’s the Third World that teaches the others the real lesson. The only character in the movie who’s really balanced is the young black, I think. I wrote his speech too; it’s coherent, though it too is in fact made up of fragments: a paragraph from the preface of Althusser’s Pour Marx, quotations from Mao, clippings from Garde Rouge. Of course, though it’s coherent, there’s still something to it that’s slightly unsettling; Pierre Daix has pointed it out: the questions they ask him have less to do with the situation they find themselves in than with much more general problems. Still, this young militant agreed to be filmed, to use his real name, and to make the slightly peculiar speech I’d written for him. But we’re talking now like men of the same world – we might say the same cell. The one really interesting point of view here would be the view from the outside – the way it would look to the Cuban movie-makers, for example. There’s a real gap between film and politics. The men who know all about politics know nothing about film, and vice-versa. So, I say it over and over again, the one movie that really ought to have been made in France this year-on this point, Sollers and I are in complete agreement – is a movie on the strikes at Rhodiaceta. They are typical-much more instructive than the strikes at Saint-Nazaire, say, because, viewed in relation to a much more “classical” kind of strike (I’m not taking into account the hardships they involved), they are, properly speaking, modern in the way the strikers’ cultural and financial griefs interact. The thing is, once again, the men who know film can’t speak the language of strikes and the men who know strikes are better at talking Oury than Resnais or Barnett. Union militants have realized that men aren’t equal if they don’t earn the same pay; they’ve got to realize now that we aren’t equal if we don’t speak the same language.

Two or three years ago, you told us you thought it extremely hard to make political movies: there’d have to be as many points of view as there were characters, and an “extragalactic” viewpoint as well, to include them all. How do you feel about it now?

I don’t think so, now. I’ve changed. I think you’re right to favor the correct view at the expense of the wrong views. The “elegant” Left would say that’s another one of the Little Red Book’s truisms though I don’t think they are truisms. If you’re not carrying out a correct policy, you’re carrying out a wrong policy. When I told you that, I was thinking that you were obliged to be objective – the way the press is “objective”: you pay everyone equal attention or, as they put it, “democratic.” But in the sketch I’ve made for Vangelo 70 it’s put quite plainly that, on the one hand, there is what you call “democracy,” on the other, revolution; that’s it; that’s all.

How do you feel now about the movie in which you first got into politics, Le Petit Soldat?

It’s okay for what it was. I mean, it’s the only movie a man born a bourgeois and just beginning to make movies could have made if he wanted to get into politics. The proof is that Cavalier used the exact same theme when he made his movie on Algeria. There just aren’t that many. It’s close to the theme of some pre-war novels, Aurelian or Reveuse Bourgeoisie – film lagged so far behind life. It’s too bad nobody else made his own movie about – the underground Jeanson organized, or the French Communist Party. They’d have been hard to make, of course. But, once again, if I didn’t know what I needed to be saying in my movie, the ones who did didn’t know how to say it in movies. My movie’s all right in so far as it’s film; it’s wrong for everything

else; which means it’s just average.

Let’s go back to the line that concludes La Chinoise. It’s put in the simple, preterite past and pronounced in a “distant” tone of voice. Mightn’t it risk, as a result, making us think everything that precedes it a phantasy, a day-dream?

It’s a simple, not a complicated past. The tone isn’t “distant”: it’s the tone of voice Bresson’s heroines always have. As for it being a “phantasy,” it’s precisely because she’s realized so much that Veronique will be able to make it something more than a day-dream. Besides, the tone in which she says the line is soft; it’s calm, like the Chinese. I was really impressed at the Chinese Embassy by how softly they speak. It’s the tone of a final report. She realizes she hasn’t made a Great Leap Forward. Just one timid ste in advance-though she has, in fact, already seen i’ots of action; she’s gone so far as to kill the man who “never wrote Quiet Flows the Don!”

A movie on the strikes at Rhodiaceta would have led to a quite different kind of realisation…

Yes, it would. But if it were made by a moviemaker, it wouldn’t be the movie that should have been made. And if it were made by the workers themselves-who, from the technical point of view, could very well make it, if somebody gave them a camera and a guy to help then1 out a bit – it still wouldn’t give as accurate a icture of them, from the cultural oint of view, as tffe one they give when they’re on thee picket-lines. That’s where the gap lies.

The movie-maker has to learn how to be their relief.

Yes, he has to learn how to take his place in the line. Learn how to pass the word along, a new way,

to others. In La Chinoise, film assumes so many, such diverse forms that they might cancel each other out. The thing is, I used to have lots of ideas about film. Now I don’t, none at all. By the time I made

my second movie, I no longer had any ideas what film was. The more movies you make, the more you

realize that all you have to work with-or against, it comes down to the same thing-is the preconceived

ideas. That’s why I think it’s a crime that it isn’t a man like Moullet whom they hire to make movies like Les Adventuriers or Deux Billets pour Mexico. The way it’s a crime that Rivette’s being forced – he

now after all the others who’ve been exploited by the Gestapo of economic and aesthetic structures erected by the Holy Production-Distribution-Exhibition Alliance – to reduce a statement five hours long to the sacrosanct hour and a half.

Do you think you’ve made any discoveries in film?

One: what you must do to be able to make a smooth transition from one shot to the next, given two different kinds of motion – or what’s even harder, a shot in motion and a motionless shot. Hardly anyone ever does it, because they hardly ever think of doing it. So, you can join any one shot and any other: a shot of a bicycle to a shot of a car, say, or a shot of an alligator to a shot of an apple… People do do it, I guess, but pretty haphazardly. If you edit not in terms of ideas, the way Rossellini edits the beginning of India – that poses quite different problems – but in terms of form… when you edit on the basis of what’s in the image and on that basis only… not in terms of what it signifies but what signifies it, then you’ve got to start with the instant the person or thing in motion is hidden or else runs into another and cut to the next shot there. If you don’t, you get a slight jerk. If you want a slight jerk, fine. If you don’t, there’s no other way to avoid it. The women who do my cutting can do it all by themselves, now. I hit on it in A Bout de Souffle and I’ve been using it systematically ever since.

You said you don’t have any ideas about film now. But it’s still very much there in La Chinoise. It’s even

thematic…

It asks questions about film because film is beginning to ask itself questions. I don’t see anyway how I could have kept it from coming into the movie less than it does – though it tends in effect, paradoxically, to narcissism. In this sense, the camera that filmed itself in a mirror would make the ultimate movie.

As in your sketch for Loin du Vietnam?

No, not entirely. There wasn’t any other way to do it, there. It had to be pushed to just that extreme. Because we are all narcissists, at least when it comes to Vietnam; so we might just as well admit it.

Your characters think the Soviet communists have “betrayed” Marxism. Do you think so too?

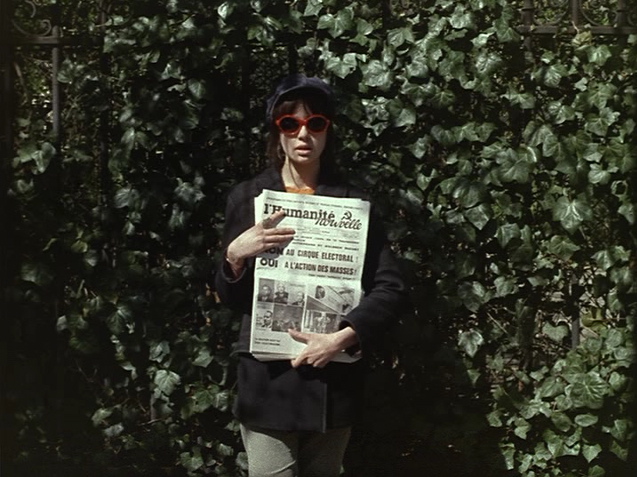

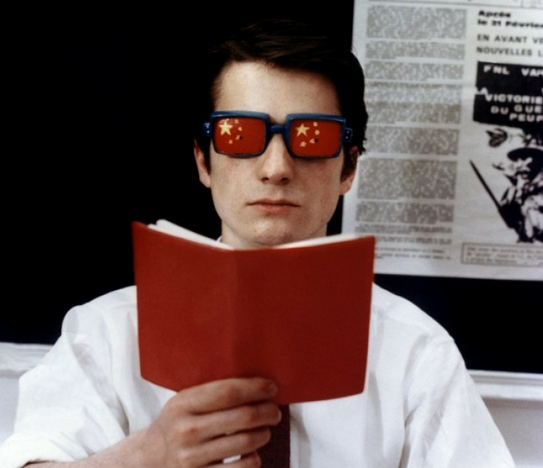

I’ve made a movie I call La Chinoise, in which I adopt, against the point of view of the French Communist Party, the point of view of the writings of Mao Tse-tung or the Cahiers Marxistes-Leninistes. I repeat, it is film that’s imposed the direction I take, which explains why the Cahiers Marxistes-Leninistes can accuse it of being “leftist” and why L’humanité Nouvelle can even attack it for being a “fascist provocation.” But, even if there is some truth in these opinions, it’s still not quite that simple; for, insofar as it’s a question of film, the question’s been poorly framed.

How do you explain the impact the revisionist Henri’s siatement has had on a good many?

I hadn’t foreseen it, but it makes sense to me now. At one point, four gang up against one. That’s all. If you’d film Guy Mollet one against four, it’s Guy Mollet, that stupid ass, who as the underdog is going to get all the sympathy.

Henri’s the only one of the five who explains himself completely.

No, you’re wrong. People think he’s the only one who explains himself “completely.” The others don’t need to, to the extent that things are just that much clearer for them. You have to take into account, too, that people are apt to favor the guy whose views they prefer; that, in any case, they’re incapable of being good listeners; and that they don’t, in addition, ever attempt to make a final accounting of what they’ve heard the characters say.

Renoir has already asked what immediate effect film might have. He’s remarked that the war broke out just after he’d made La Grande Illusion – a movie in behalf of peace.

Exactly. Film hasn’t the slightest effect. They thought, once, that L’Arrivée du Train en Gare would scare people out of their seats. It did – the first time, but never again. That’s why I’ve never been able to understand censorship, not even its ontological grounds. It seems to be based on a notion that image and sound have an immediate effect on the way people behave.

Though you can’t really trace the influence an image exerts…

Correct. But, then again, no more and no less than the effects any of the rest might have – in other words, no more than you can the effects of the whole thing. Because everything exerts some influence. If you leave out that part of film that people call “television,” we could say that film “has the influence” of scientific research, theater, or chamber music.

Does this diminish your confidence in film?

No, not at all. But you’ve got to realize that the millions of people who’ve seen Gone with the Wind have been no more influenced by it than the many fewer who’ve seen Potemkin. There’ve been some

attempts to blame film for juvenile delinquency. But the people who’ve tried it don’t seem to have noticed that in precisely the same period that juvenile delinquency was on the rise in the USA, movie-attendance was dropping off sharply. The sociologists haven’t even begun to study the question.

The first shots you’ve ever made of the rural scene come in La Chinoise: the two shots of the countryside that remarks on the farm-problem accompany off…

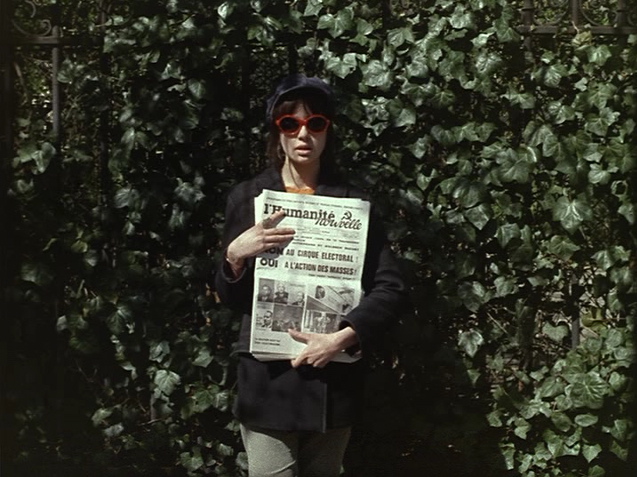

Yes. L’Humanité called them picture-postcards. I don’t know. All I can say is, as soon as we saw a meadow, a cow, and some chickens, we stopped the car and shot some footage. Then we turned around and drove home. I don’t see anything wrong in that. I had to have these shots, because Yvonne had come up from the country, and because one of my characters had a couple of things to say about rural problems.

The character Juliet Berto plays is new for your film.

I wanted something besides Parisians. I wanted someone who’d come up from the country, so I could illustrate another of the vices of our society: centralization. Someone, too, who in contrast to the others has nothing, who’s dispossessed. Someone sincere, who has a feeling there’s something their little group can do. She has access through them to the culture that’s been refused her. She used to think it dropped from the skies. Then she started reading the papers. Now she’s selling them. It’s a first step.

In the traveling shot along the balcony during the theoretical presentations, the division of space by the three windows divides the “class” into three groups: “professor,” and Yvonne, the maid, who’s shining shoes or washing dishes the whole time.

I had to show that even for those who’d like to live without them, social classes still exist. It’s just at that moment you hear someone asking, “Will class struggle always exist?”

The first two categories – “professor” and “students” – can still relate, interact. But the third is effectively kept to the side.

But it’s only physically, not mentally, that she’s “forbidden” a part in the discussion. Or else it’s “tactically”: because at the end of the movie she’s no longer forbidden to take part in it all. For one thing, she’s voted. There’s no doubt she discovers that it’s she who, in the final analysis, has come much closer to the others than they have to her personal reality – which they should have explored, but they haven’t; they’ve put if off. So, of all the characters it’s the little farm-girl who covers the most ground. Then comes Léaud, then Anne, then Henri.

The movie is made up of a series of short sequences that seem to be quite independent of one another.

It’s the kind of movie that’s made in the cutting. I shot self-contained sequences, in no particular order;I put them in order afterwards.

Does that mean it might have been diferent?

No, it doesn’t. There was an order, a continuity that I had to find. I think it’s the one that’s in the movie. We shot it …in the order that we shot in! Though as a rule I shoot the sequences in order, in some kind of continuity; I mean, with some clear idea of the movie’s chronology and its logic – even if I’ve found myself having to change the order of whole sequences. This is the first time the order in which I shot a movie presupposed nothing. It happened, of course, that I’d know right when I shot them that two different shots would go together – two shots in the same discussion, for example; but not always… For the most part they were independent. The linking came later. So they aren’t independent now; they’re at least complementary if not also coherent.

That was the point of view on which you relied? Was it some notion of a purely logical kind of coherence? Or was it emotional? Or was it simply a visual coherence?

Logical. Always. But logic can be conveyed in a thousand ways. Let’s take an example. One of the texts in the presentation is a speech of Bukharin’s. Right after it’s read there comes a title: “Bukharin made this speech.” Next, you see a photo of Bukharin’s accuser. Of course, I could have used a photo of Bukharin himself. But I didn’t need to: you’d just “seen” him in the person who reads the speech. So, I had to show his adversary: Vichynski and, eventually, Stalin. okay: photo of Stalin. And because it’s a young man who speaks in the name of Bukharin, the Stalin in the photo is young. That takes us then to the time when the young Stalin was already at odds with Lenin. But by that time Lenin was married. And one of Stalin’s greatest enemies was Lenin’s wife. So, right after the photo of the young Stalin: photo of Ulianova. That’s quite logical. What has to come next? Well, it’s revisionism that toppled Stalin. So, next, you see Juliet reading an ad in France-Soir: Soviet Russia is busy publicizing Tsarist monuments. Right after you see the men who in their youth killed the Tsar. It’s a little like a theorem that presented itself as a puzzle. You have to see which pieces fit. You’ve got to use induction, feel your way, deduce. But, in the final analysis, there’s only one possible way to fit them together, even if you have to try several things to find it.

So what you do when you edit is work that most movie-makers do in their shooting-scripts.

In a sense, yes. But it’s work that just isn’t interesting if you do it on paper. Because if it’s paper work you like, I don’t see why you make movies. On this point, I’m in agreement with Franju: as soon as I’ve imagined a movie, I consider it made: I can more or less tell it; so why should I go ahead and shoot it? Oh, to do right by the public, I guess: Franju says it’s “so the public has something to chew on.” He says something like this: “When I’m done with my eight hundred pages, I really don’t see what else I’ve got to do. So they want me to shoot it. Okay. I shoot it. But it’s all so depressing, I have to get drunk first.” There’s just one way to avoid that: don’t write scripts.

So it’s us if you shoot in the dark, but in complete freedom too?

No, that isn’t it. It’s only in shooting that you find out what you’ve got to shoot. It’s the same thing in painting: you put one color next to another. Because you make film with a camera, you can just as easily get rid of the paper. Unless you decide to do what McLaren does – and he’s one of the greatest men working in film – and write your movies right on the stock.

So when you shoot it’s as if you collect a lot of stuff you have to sort later…

No, it isn’t. It’s not just “a lot of stuff.” If it’s a “collection,” it’s a collection that always has a particular end in view, a definite aim. And it isn’t just “any” movie: it’s always a particular movie. You “collect” only the stuff that can meet your needs. It’s almost the reverse for my next movie: the structure’s all there; it’s entirely organized. All I had for La Chinoise were the details, lots of details I had to find how to fit together. I’ve got the structure for Weekend,but not the details. It’s sort of frightening: what if I don’t find the right ones? What if I can’t keep my promise- because, after all, for the money they give me, I promise to make them a movie. No, that’s all wrong. You shouldn’t think about work in terms of a debt or a duty – in the bad sense of the word; you should think about it in terms of some normal activity: leisure, life, and breathing evenly; the tempo has to be right.

One of your characters says that Michel Foucault has confused words and things. Do you share his opinion?

Oh God, the Reverend Doctor Foucault! The first thing I did was read the first chapter in his latest book, the analysis of Velasquez’ las Meninas. I skipped through the rest of it; I picked up a little here and there – you know I can’t read. Some time later I was at Nanterre, looking for locations. In talking to students and professors there, I began to appreciate the real inroads the book had been making in the academic establishment. So I went back to it again, with this in mind. It began to look really debatable. The current vogue for the “humanities” in the daily press seems very suspicious. I heard that Gorse had been thinking about making Foucault head of the Radio-Television. I have to admit I preferred Joanovici.

In this connection, how do you view the use of linguistics in the study of film?

As a matter of fact, I was just talking about it with Pasolini, at Venice. I had to talk to him because, as I’ve told you, I can’t read, or at least not the stuff men like him have been writing about film. I just don’t see the point. If it interests him, I mean Pasolini, to talk about “prose film” and “poetic film,” okay. But if it’s somebody else, well… If I read the text on film and death Cahiers published in French, I read it because he’s a poet and it talks about death; so, it’s got to be beautiful. It’s beautiful like Foucault’s text on Velasquez. But I don’t see the necessity. Something else might be just as true. If I’m not so fond of Foucault, it’s because he’s always saying, “During this period, people thought ‘A,B,C’; but, after such and such a precise date, it was thought, rather, that ‘1,2,3’.” Fine but can you really be so sure? That’s precisely why we’re trying to make movies so that future Foucaults won’t be able to make such assertions with quite such assurance. Sartre can’t escape this reproach, either.

And what did Pasolini say?

That I was a stupid ass. Bertolucci agreed, in the sense that I’m too much of a moralist. But… Well, I’m still not convinced. It means you’re going to wind up in the kind of “filmology” they used to teach at the Sorbonne, or even something much worse. Because, when you get right down to it, Sam Spiegel’s in complete accord with all this stuff about “prose film” and “poetic film.” Though he’d say that “he’s going to make ‘prose film’: ‘poetic film’ bores the public shitless.” It’s the same old thing all over again: people borrow and then distort some interesting ideas; Hitler revisiting Nietsche… I view linguistics the way Leclerc might – or, even worse, Poujade. But I still have to agree with Moullet. At Pesaro he talked commonsense…

But it’s precisely a man like Levi-Strauss who refuses to make random use of linguistic terminology. He uses it only with the greatest caution.

I agree. But when I see him use Wyler as an example when he talks about film, it makes me unhappy. I tell myself that if he, as an ethnologist, prefers the Wyler tribe, I much prefer the Murnau tribe. Here’s another example: Jean-Louis Baudry has published an article in Les Lettres Francaises. As I was reading it, I kept saying, “This is really good writing! Here’s a guy who ought to write something on Persona. He’d do a really good job.” This thing is, the article I was reading was supposed to be an article on Persona. Metz, too; he’s a peculiar case. He’s the easiest to like of them all: because he actually goes to movies; he really likes movies. But I can’t understand what he wants to do. He begins with film, all right. But then he goes off on a tangent. He comes back to film from time to time; he’ll poke around in it for a bit. But then he’s off again on another track. What bothers me is that he seems not to have noticed; it’s unconscious. If it were a question of research in which film were only a tool, I’d see no objection. But if it’s film that’s supposed to be the object of the research, then I don’t understand. It’s not that there’s contradiction in what he’s doing; it’s more like some real antagonism.

But Metz just isn’t interested in what interests us.

All right. But there’s still some common ground it’s all got to be based on. The way it looks to me, they leave this common ground much too often. I can understand, in some general sense, the intuitions Pasolini begins with; but I don’t see the need for the logical development that follows. If he thinks a shot in a movie of Olmi’s is “prosaic” and a shot in a movie of Bertolucci’s “poetic,” all right. But, objectively, he could say just the opposite. Their tactics resemble Cournot’s when he rejects one whole kind of film because, in his view, it just “isn’t film”; so, he’s forced to reject Ford; but only because he can’t tell Ford from Delannoy! That’s not in the least enlightening. This all brings to mind Barthes’ recent book, the book on fashion. It’s impossible to read, for one simple reason: Barthes reads things he ought to be seeing and feeling instead: it’s something you wear, so it’s got to be something you live. I don’t think he’s really interested in fashion: it isn’t fashion as such that attracts him; it’s some kind of dead language that he can decode. You had the same kind of thing at Pesaro. Barthes scolded Moullet the way a father scolds his kids. But we’re the sons of a filmic language; there’s nothing in the Nazism of linguistics we have any use for. Notice: we always come back to how hard it is for us all to be talking about “the same thing.” The people who publish Tel Quel seem capable of making some really basic discoveries in science and literature. But as soon as it’s film, something seems to elude them. Men who know film really well talk about it in quite different terms – whether it’s you on Cahiers or Rivette and I when we’re talking about the movies that have just come out or the people on Positif when they’re talking about Jerry Lewis or Cournot when he says of Lelouch that “it isn’t a question of ‘feeling,’ but it isn’t a question of ‘thinking’, either.” This reminds me again of the talk I had with Sollers. He reproached me for talking “in examples.” “He said I kept saying “it’s the same thing as” or it’s like.” But I don’t talk “in examples.” I talk in shots, like a movie-maker. So I just had no way to get him to understand me. I’d have had to make a movie we could have talked about afterwards. What it signifies on the screen for him is maybe what “signifies it” for me. There’s got to be something right there that we’ve got to clear up; it’s probably pretty simple, too. It’s somewhat similar with painting: if Elie Faure moves us, it’s because he talks about a painting as if he were talking about a novel. Somebody should finally get around to translating the twenty volumes of Eisenstein that nobody’s read: he’ll have dealt with it all in very different terms. He began with technique, too, the very simplest problems, so he could get on to the hardest. He goes from the travelling to Nô theater so that he can get back to explaining the Odessa Steps. The place to look for an ideology is in a technique. The way Regis Debray finds the revolution in Latin America in the guerrilla. The only thing is, the ideology of film has so decayed, it’s so rotten that it’s harder here to make a revolution than anywhere else. Film is one of the things that exists in purely practical terms. You’ll find that here, too, the economic forces at work have laid

down an ideology of their own that has, little by little, eliminated all the rest. The others are beginning

to re-emerge, right now; some of the best are among them. In this connection, a lot of the stuff Noel Burch has written is very interesting. What he has to say about raccords is stictly practical. You have a feeling they’re the view of a man who’s done it himself, who’s thought about what is involved in doing it – a man who has come to certain conclusions on the basis of his physical handling of film. Well, all you’d need to get it all down in a orderly list is some serious, well-organized team-effort. The best work a new nation could do to get started is something along those lines. All they’ve got to do is buy some good movies, start a film library, and study movies. They can make them later. They can learn while they’re waiting. Before getting yourself involved with what the linguists call a “scientific” analysis of film, you’d do better to list the scientific facts of film. Nobody’s done it. Though it still could be done: the projections at the Grand Caf6 weren’t that long ago; Niepce’s first plates are still at Chalon. But if you wait too long, you won’t be able to do it. Movies disintegrate. Even books fall apart. Movies fall apart a lot faster. In two hundred years you won’t be able to find a single one of our movies. There’ll be a few bits and pieces – of bad movies as well as the good: the laws to protect the good movies still won’t have been made. So, the art we’re working in is really short-lived. When I started to make movies, I thought film something that lasts forever. Now I think it something really short-lived.

So the incompatibility in the language of the writers and movie-makers is just as severe as it is for movie-makers and the strikers at Rhodiaceta – though the writers have already had a good deal to say about film.

Well, if they have, it’s often only because movies sometimes refer to literary forms or simply just cite literary texts.

Do you think it’s your use of collages that leads Aragon to write about you?

Maybe it’s the digressions that have attracted him: the fact that there’s someone who uses them as digressions, besides as a structural device. In any event, Aragon is a poet, which means that anything he has to say is beautiful. If you don’t talk about films in poetic terms, then you’ve got to be talking about it in scientific terms. We haven’t reached that point yet. Notice this one simple fact: you go to a theater to see a movie; you never ask why; though there is simply no reason why movies should be shown in theaters. This in itself is revealing. Of course, they way things are, you’ve got to have theaters. But they shouldn’t be more than something like a deconsecrated church or a track field: you should hold onto them; people will go a theater to see an occasional movie; there’ll be a day when they’ll want to see a movie on a big screen; or like the way an athlete will go out to train by himself in the middle of the week; he wants to be far from the frenzy, the racket, the drugs of the weekend meets. Ordinarily, you should be able to see movies at home, on a television set or a wall. It’s feasible, but nobody’s doing anything about it. For a long time, now, the factories ought to have had screening-rooms; someone should have investigated what increasing the size of TV screens involves, practically. Nobody has. They’re all scared

Do you think there is a connection between the ways film is distributed and exhibited-theaters, chains, and so on-and its aesthetics?

If these conditions were to change, everything else would change, too. A movie is subject today to an unbelievable number of really arbitrary rules. A movie is supposed to last an hour and a half. A movie is supposed to tell a story. All right. A movie tells a story. We all agree. The only thing is, we don’t agree on what a “story” is, what it’s “supposed” to be. You see, today, that the silents had immeasurably more freedom than the talkies – or, at any rate, what they turned the talkies into. Take as unimaginative a director as Pabst: he gives you a feeling that he’s playing a grand. A movie-maker today who has no more than Pabst’s talent, if he analyzes his own case correctly, has to feel that he’s playing not much more than a toy. It’s all a state of mind. For example, when someone’s building a theater, he never takes the trouble to ask the advice of a cameraman or a director. And nobody’s ever going to ask advice of a viewer. So, as a result, the three most interested parties never have a chance to make their desires known. It’s true they build houses this way too. But the guys who design theaters are always the worst they can find. And they’re never the ones who go to see movies.

What could we do, at short range, to change it?

The best we can do is attack the technical problems, everything that results from the economic forces at work in film: production, processing, projection… The young men who are just getting their start in film don’t have to know everything about it. They can get along very well without knowing anything about Lumicre or Eisenstein. They’ll run into them sooner or later themselves. The way it isn’t until he was thirty that Picasso got onto African art. And if he hadn’t just then he’d have painted Les Demoiselles d’avignon a few years later. He’d have done something else in the meantime. The young men have all the luck: they can always start over. People have been doing a lot they can benefit from, even if it’s been fairly haphazard, disorganized. They need to make a long list, get everything on it, the little things as well as the most important: everything involved in film that lust won’t do. Everything: from theaterseats – the worst are in the art-houses – to editingtables. I bought an editing-table recently. It didn’t take me long to discover that nobody had asked the right questions. They’re manufactured by men who’ve never done any editing. I’m holding onto it. I’m hoping I’ll get the money to have it rebuilt, so that it will work right

In what sense has it been badly conceived?

The way they’re manufactured is the result of a particular aesthetics. They’ve been conceived as little projectors. That’s fine for men who think editing a few pencilled notes: the director shows up Monday morning; he tells his cutter where to make cuts and splices; she takes the footage off the editor and does the work she’s been told to do at another table. Or, if it’s someone like Grangier or Decoin she works for – they just can’t be bothered, she’ll do the whole thing herself. But in any case, the real editing gets done somewhere else, not at the editing-table itself. But, there are movie-makers – Eisenstein’s the first, Resnais is the second, I’m the third – who do their editing, each in his own way, of course, right at the editing-table, with the image and against the sound. The problems you have with handling the film are completely different. I keep winding the film back and forth. I make splices without ever taking the reels off. And if the table hasn’t been manufactured with work of this sort in mind, it’s not easy to do it. Again, it comes down to a simple economic gimmick that all by itself bears out a whole ideology. If that’s how they manufacture editing-tables, it’s because three-fourths of the people editing film edit this way. Nobody’s ever told the manufacturers to do it differently. I use editing as an example, but the same kinds of thing turn up everywhere else. If you’re trying to make revolutionary movies on a reactionary editing-table, you’re going to run into trouble. That’s what I told Pasolini: his linguistics is a shiny, new, reactionary editing-table. Besides, the more movies I make, the more I realize just how precarious a thing a movie is: how hard it is just to get it made, and then how hard it is to get it shown – in other words, just how distorted the whole thing is. If problems like these were ever solved – though I don’t think they’ll ever be solved in the West-then we just might discover some new ways of working-ways to make film that’s really new. Things as new as the discoveries made in the very first years of film. Everything we’re using now was invented in the first ten or twenty years of the silents. Technique was moving right in step with production and distribution, then. Right now, we’ve lost sight of the ways they’re connected. Everything goes its own way – if you think it’s going anywhere at all. The only thing I’d want to write for Cahiers now – it would take time to do it; I’m always running into something else to say on the subject would be something about the ways to get film off to a complete new start. I’d discuss it in terms of the problems a young African would have to face. I’d tell him, “All right, your nation has just won its freedom. Now that you’re free to have a film of your own, you and your comrades have been asked to get it started. Okay. Get Jacquin and Tenoudji out of your theaters.” – You know, even in Guinea, the most revolutionary of the new nations, the theaters all still belong to Comacico. And, though the Algerians have nationalized their filmindustry, they’ve handed it right back to the distributors, which means that in no time at all it’ll be back in private hands again; it’ll be just the way it was before. “You’ve decided to have a film of your own, to make film of your own. This means that you’re not going to import any more trash like La Marquise des Anges. Book Rouch’s movies, or movies made by some young African he’s trained – anything that interests you. If you work for De Laurentiis, don’t go to him. Make him build studios for you here. In other words, since you have it all still to do, turn it to your advantage. Make a thorough investigation of everything that’s involved in the production and distribution of movies. Build or rebuild your theaters – or what might replace them in the eyes and the hearts of your militant countrymen.” Things like that. It’s impossible to list the mistakes that have to be corrected. You’d have a list as long as the lists in Rabelais or in Melville. But you’d have to try, if you really wanted to redefine film. To get back to Algeria: They should use the money they’ve made in co-production deals to build processing plants of their own, not in financing (aside from a couple of things like Le Vent des Aurès) Jacquin’s movies: I know it’s hard to believe, but half the money in Le Soleil Noir is the Algerians’. They haven’t even got their own processing plants: they send their newsreels to France or Italy, on Air France or Alitalia; they don’t trust Air Algeria.

It’s sometimes only too obvious that movie-makers in the new nations imitate the very worst in our film when they’re making their own first shorts.

Of course it’s also an individual, a mental problem. But if you want to get off to a start, you’ve got to base yourself on a non-mental thing-on technique. The new mentality can develop out of it. Obviously, things are hard, everywhere. The director of the Algerian Film Center is convinced he’s better off having Jacquin or Tenoudji distribute his movies. That’s the tragedy of the Third World: it’s always in a corner, always in a jam for money. Everyone’s in league against it, the way they’ve all ganged up against the unemployed. The Algerians produce Italian movies instead of movies by young Algerians. They did give them some film, but the kids used it to make irresponsible junk. They’d do better, in such a case, to put a stop to their production for a time and give the kids the opportunity and the time to do a little homework, research, and to see as many good movies as possible. The crisis will take care of itself. Or they could put them to work in television or in the processing plants and the sound studios. It would be all that more practical because no director, anywhere, really knows what goes on in an editing-room or a film lab. Everybody in film ought to get some training in the sector closest to his own. Cameramen, for example. They learn a little in school, but then they never go on to get some training in the film labs. As a result, the cameraman and the lab are never able to reach an understanding. Let’s say you shoot a movie with a man who’s a real master of light. Let’s say he’s as familiar with Renoirs as with Rembrandts. Fine. The print will be timed by a man who hasn’t the faintest idea what lighting is. No more Renoir’s than Rembrandt’s. So, as a result, the print will be too dark, or too light, but in any case flat. Simply because the lab technician neither knows what he can nor what he should do. Or just the opposite. I just remembered that Matras, when he was in Madrid, spent his time sending his wife Mexichrome postcards instead of looking at pictures in the Prado. You run into the same thing at every level in film. Nobody’s really been educated. It’s a question of education. Right here in France, there’s all you’d need to make really good movies. But the men who are supposed to be directing the work are lazy bums or highway-robbers. They employ honest men, but they give them no training and no responsibilities. The people who do the actual work think they’re doing it right. But, the thing is, they’re imprisoned in a whole system of economic and aesthetic preconceptions. What You have to do, then, is explain it to them. For example, you can explain to a projectionist that there just isn’t any point in closing and opening the curtains: film isn’t theater … And if projectionists are so badly paid, it’s because no one thinks the work they do is work of any real importance. There’s as little respect for them as there is for the grips or the sound-men. A grip knows a good deal. He can, often, talk much better sense about film than his director. But he “doesn’t count.” And as for the men who manage the sound, they’re paid even worse than the men who make the image. Why? It’s a result, once again, of a whole ideology. So they say, “Why should we pay the sound-man as much as we pay the director of photography Film is the art of the image!” That’s all wrong. But the sound-man continues to get half what the cameraman gets -and, what’s worse, to think it fair. If we start talking about distribution, we run right into another problem: the distributors. Film got off to a start without them. All it took was a cameraman and a director. What did Lumiere do? He took his movies right to the guy who ran the Grand Café. All right. But since then, distribution has become a trade. The middlemen – the distributors – are lazy. They don’t make a move. But they still keep on saying (and it’s as much for themselves as it is for us), “You can’t do without us. It’s all got to go through us.” But the only reason that there are “distributors” at all is that everyone else is too lazy. The exhibitors won’t move an inch to find the product to sell. The producers won’t move an inch to take it to them. As soon as that happens, they need the third man – who robs them blind in the end…

You want to: make different movies. But to be able to make them, you have to work with people you despise and dislike, instead of with people you like and admire. The industry’s rotten to the core: from the point where the film is processed to the point it must reach – if it ever gets there -to reach a public. From time to time, of course, there’s a hint things are beginning to move. The Hyeres festival, for example, isn’t ideal, but it’s still a lot better than Cannes; and Montreal’s better than Venice. You’ve got to keep moving ahead. Film in Canada is an interesting case. The National Film Board is a real movie factory. They’re making more movies than Hollywood now. A beautiful set-up. But what happens? Nothing. There’s nothing to see. Their movies never get shown. One of the first things Daniel Johnson should do is nationalize the theaters in Quebec. In Canada, too, film is subject to the imperialism that prevails everywhere else. Those of us who keep trying to make movies differently have got to organize a fifth column, attempt to destroy the whole system.

But some film is already being made outside the system…

Yes, of course. Bertolucci isn’t making American movies. Neither is Resnais, or Straub, or Rosselllini, Neither is Jerry Lewis. But even this different film, good or bad, is no more than 1/10000 or 1/100000 of what’s being made.

But is there still a really “American” film?

No, there isn’t. There’s a counterfeit that calls itself “American,” but it’s only a very poor copy of what it was once.

Would you work for an American company again?

Yes, I would. If that’s what I’d have to do to make a movie. Or if it gave me a chance to make an expensive movie, like Michael, Circus Dog; I mean, a movie for which more money goes into the image than into the actors’ pockets. In saying this, though, I don’t compromise myself or my view of America and the imperialistic policies of its giant film companies. In the first place, there are Americans and Americans, good ones and bad ones. In the second place, there, too, they need a fifth column. You might get it into their heads that they could make different films too. You might even get them to want to. If the movie you made were a success, you might, little by little, get them to change their system themselves. It would be hard. You keep running into their imperialism at every level of production and distribution. But you’ve got to hold onto the hope. People can change. Then again, something is on the move in America right now. You can see it among the blacks and in the opposition to the war in Vietnam. And as for film, the universities are beginning to distribute movies; they’re turning into real chains. New companies are being formed. I sold La Chinoise to Leacock’s. Anyway, the world’s a little bit larger than America. But if I put the Americans and the Russians together into the same bag, it’s because their systems are almost identical. They both treat their young movie-makers like naughty children. Every one of the Americans we really admire got his start in film at an early age. They’re old now, and there’s nobody there to take over. When Hawks got his start, he was Goldman’s age now. Goldman’s all by himself. Obviously, there are young men still who do get into Hollywood, but none of them have anything like Hawks’s ideas. They’ve gotten what training they have in structures that are on their decline; they haven’t had the guts to destroy them. It isn’t in freedom that they come to film; though it isn’t in any real poverty, either, aesthetic or otherwise. They are neither explorers nor poets. But the men who made Hollywood were poets-even gangsters, who took it by force to dictate their poetic law. The most courageous man in Hollywood today, the only man who’s managed to get out from under it, is Jerry Lewis. He’s the only one in Hollywood who’s doing something different, who remains outside its categories, its norms, its principles. Hitchcock did for a long time. But Lewis is the only man who’s making courageous movies right now – and I think he’s aware of it. He can get away with it because of his personal talent. But who else can? Nicholas Ray is typical of the point American film has now reached. The case of the New York School isn’t encouraging, either. They’re already buried. And if it’s “underground” film they want to make, it’s got to mean they’d like to be buried deeper. I don’t see why. The Russians haven’t helped Hanoi bomb New York. Why do they want to live underground? There are going to be more great American movie-makers. They’ve already got Goldman, Clarke, Cassavetes. We’ll just have to wait, help them, even push them. I was talking about the universities. Film’s being made in the universities-or, at least, they’re beginning to; there didn’t use to be any film there. That’s important. Film’s got to go everywhere. We should list the laces it hasn’t been yet and then say that that’s w fiere it’s got to go. If it’s not in the factories, it’s got to get into the factories. If it’s not in the universities, we’ve got to get it into the universities. If it’s not in the brothels, it’s got to get into the brothels. Film has to get away from where it is now and go where it hasn’t been yet….

Where and when you get your start has a lot to do with how you get started. No one in France had been taking film seriously. Then people turned up who were saying you had to, that it deserved some serious thinking. For the same reasons, we had to say, too, that there is such a thing as a “work.” I don’t think now that there is. That’s a point you reach if you push your thinking on art just a little bit further. There is no such thing as a “work,” even if there is something that’s kept in cans or printed on paper, not in the way that there are such things as beings or objects. But, at the time, that was the thing we had to do first: force it on people that there was “work,” even if you have to tell them now that they’ve got to go a little bit further in their thinking. In the same way, I’ll say too that there is no such thing as an “author.” But to get people to understand in what sense you can say that, you have to tell them over and over again, first, that there’s such a thing as an “author.” Because their reasons for thinking there weren’t weren’t the right ones. It’s a question of tactics…

Aren’t you increasingly influenced by theater?

You’ve got to do theater in film, I think – mix things up a little. Mix it all up. Especially the festivals. I think it’s absurd that they don’t hold the music and theater festival at the same time as the film festival at Venice. They should have music one night, film the next …. You remember how it was at Pesaro: after you’d seen a movie you could go and hear jazz; you had a really good time.

But when you say that, you’ve begun to attack one of the public’s biggest taboos – against the mixing of genres. You begin to realize the damage done some thirty or forty years ago when the “theoreticians” would decree that something “was theater, not film.”

There are a lot of movie-makers right now who’d like to talk about theater: there’s Rivette and L’Amour Fou; Bertolucci and others. Persona, Blow-Up, Belle de Jour are part of it, too. And Shakespeare Wallah; that’s a beautiful movie. I suppose it means that people who’ve gotten the feeling they’re trapped by their means of expression want to get out of it. I’m not talking about Bergman now; he’s been doing theater all his life; he’s done more theater than he’s made movies. For a long time, now, I’ve been wanting to make a didactic movie on theater, about Pour Lucrèce. At the beginning you’d see the girl who’d act the role get out of a cab; she’d be going to a rehearsal; no, not a rehearsal; she’d be going in for an audition. Then you’d get into the play. You’d see an audition, a rehearsal, a scene in performance. From time to time, there’d be some critique of the play itself. Some scenes would be done two or three times: the actors would make mistakes or the director would want to get something just right. You could have the same scene done by several actors: Moreau, Bardot, Karina could each act the same role. And the director could review the seven or eight great theories of theater with the actors: Aristotle, the three unities, the Preface de Cromwell, The Birth of Tragedy, Brecht and Stanislavsky – but they’d be doing it in the play, still. At the end, the girl you saw coming in at the start would die: because Lucrece dies; you wouldn’t know where the fiction stopped, then. A movie like this would aim to teach an audience what theater is. Readings are just fantastic! When you get right down to it, the most fantastic thing you could film is people reading. I don’t see why no one’s done it. Film someone who’s simply reading… The movie you’d make would be a lot more interesting than most of them are. Why couldn’t film mean filming people reading really fine books? Why shouldn’t you see something like that on TV, especially now that people don’t read much? And people who can tell good stories, make them up – like Polanski, Giono, Doniol. They could make u stories right in front of a camera. People would listen to them. If somebody’s telling a really good story, you can listen for hours. Film would be going back to the traditions and role of the Oriental storyteller. We lost out on a lot when we stopped being interested in storytellers. But the ideology that tells us what a spectacle “is” is so firmly established that the people who’d been spellbound by the story you’d been telling them at the Gaumont-Palace would come storming out in a rage; they’d say you’d tried to take them for fools; they’d say they’d been robbed.

But you don’t question spectacle itself…

No, I don’t. If you look at something, it’s a spectacle, even if it’s just a wall. I’ve always wanted to make a movie about a wall. If you really look at a wall, you wind up seeing things in it.

One gets the impression that there’s an intention to destroy the image itself at work in your sketch Anticipation, to destroy it as the support for “realism.

It annoyed me that it was much too easy to identify the actors. When I started shooting it, I still hadn’t thought of anything like it. It was only later that it occurred to me to give the movie – you could call it a “biological” look-like plasma in motion. But plasma that speaks. But the minute you do that, you attack an idea that’s almost sacred: the idea that an image in film is sharp, clean, “solid” … But an image is always an image, as soon as it’s projected. So I haven’t destroyed a thing. Or else, one idea of the image and what it’s supposed to be. I never thought of it as destruction… What I wanted was to get inside the image, because most movies are made outside the image. What is an image? It’s a reflection. What kind of thickness does a reflection on a pane of glass have? In most film, you’re kept on the outside, outside the image. I wanted to see the back of the image, what it looked like from behind, as if you were in back of the screen, not in front of it, Inside the image. The way some paintings give you the feeling you’re inside them. Or give you the feeling you can’t understand them as long as you stay outside them. Red Desert gave me the feeling the colors were inside the camera, not out there in front of it. The colors are all in front of the camera in Le Mépris. You’re convinced it’s the camera that makes up Red Desert. In Le Mépris, there is the camera, on the one hand, the objects on the other, outside it. I don’t think I’d know how to make up a movie like his. Except that I’m beginning to want to. You can see my wanting to in Made in USA. That’s why people haven’t understood it. The people who’ve seen it think it’s supposed to be “representational,” but it’s not. I must have put something over on them, because they kept trying to follow it “representationally”: they kept trying to understand what was happening. They did keep up with it, quite well. But they didn’t know they had: they kept thinking they hadn’t understood a thing. It really impressed me that Demy was so fond of Made in USA. I’d always thought it a movie “in song”; La Chinoise is a movie “in talk.” The movie Made in USA resembles the most is Les Parapluies de Cherbourg. The actors don’t sing, but the movie does.

Now that you bring up resemblance, is there a connection between Persona and your last few movies?

No, I don’t think so. And anyway, I don’t think Bergman likes my movies too well. I don’t think he’s taken anything from me – or from anyone else, for that matter. Anyway, after In a Glass Darkly, Winter Light, and The Silence, he could hardly have made anything but Persona.

Persona is much more daring stylistically than the preceding movies. The way the narration is “doubled,” for one thing…

No, I think the shot you’re talking about is, aesthetically, just a continuation or a development of the long shot in Winter Light in which Ingrid Thulin confesses. But it’s much more striking in Persona, of course; it’s close to formal aggression. It’s so striking as a formal device that as soon as you see it you tell yourself “it’s so beautiful; I’ve got to use it in a movie myself.” I got the first shot for my next movie when I was seeing Persona again. I told myself that what I needed was a fixed-frame shot of people talking about their genitals. But in another sense, it reminds me of the opening shot in Vivre sa Vie: I stayed behind the couple during the whole shot, but I could have gone round in front. What he’s doing is something like what the interviews are in my movies; it’s very different in Bergman, but, in the final analysis, it always comes down to the desire to represent a dialogue. And it has something to do with Beckett, too. At one time I’d wanted to film Oh! les Beaux jours. I never did – they wanted to use Madeleine Renaud; I wanted to use young actors. I’d have liked to – I had a text, so all I’d have had to do is film it. I’d have done it all in one continuous travelling. We’d have started it as far back as we had to to get the last line, at the end of an hour and a half, in a close-up. It would have meant just some grade-school arithmetic.

How do you interpret what in Persona keeps reminding you it’s a movie you’re watching?

I didn’t understand Persona. Not a thing. Oh, I did watch it, carefully. This is the way it looked to me: Bibi Andersson is the one who’s ill; it’s the other girl who’s the nurse. When you get down to it, I guess I always rely on the “realism.” So, when the husband thinks he recognizes his wife, I think she’s his wife: he’s recognized her. If you didn’t rely on realism, you’d never be able to do anything. If you were on the street, you wouldn’t dare to get into a cab – if you’d even risked going out, that is. But I believe in it all. You can’t divide it up into two; you can’t separate the “reality” from the “dream”; it’s all one. Belle de Jour‘s really great. There are moments when it’s just like Persona. You say, all right, beginning now I’m going to follow it carefully, so I’ll know just exactly where we are; then, all of a sudden, you have to say, damn it!we’re already there: you see you’re already in it. It’s as if you decided you wouldn’t go to sleep so that you wouldn’t be asleep when you went to sleep. That’s the problem these two movies pose. For a long time now, Bergman’s been at a point where it’s the camera that makes the movie, eliminating everything that can’t become part of the image. That ought to be axiomatic for all editing, and not notions like “the pieces have to be put together in just the right order,” or “there are rules that must be observed.” You ought, instead, to say that you’ve got to eliminate everything you can say. Even if you have later to turn it all inside out and say that all you can keep is what is said. That’s what Straub, for example, does. In La Chinoise, it’s only what’s said that I keep. But the result is completely different from Straub’s, because it isn’t the same thing that’s said. Bunuel eliminates everything that is said, since even what’s said is there to be seen, too. There’s a fantastic freedom in his movie. You get a feeling that Bunuel can “play” film the way Bach must have played the organ at the end of his life.

How do you view the notion of the “door-to-door theater” Leaud picks up on at the end of La Chinoise?

I’m afraid it hasn’t been understood. I suppose I didn’t make it clear enough. It’s not he who’s in question; it isn’t an individualistic solution. The way I’d been thinking about it, I’d have had to show him together with others. One would have been playing a guitar; one would have been singing or drawing on the sidewalk- the kinds of things hippies do in front of cafes. But this time they’d be communists doing them. They’d have been doing real work: they’d be having to choose their text for the given situation, switching from Racine to Sophocles or something else. I really ought to have had more than one doing it. There’d have been times when they wouldn’t know what to say; they’d have to talk it over, to decide which was the right response. They might even start talking to the people watching them, engage in real dialogue. Instead of acting theatrical texts, they could have recited some Plato. There shouldn’t be any restrictions. It’s all theater; it’s all film; it’s all science and literature. If you’d mix things up a bit, we’d all be a lot better off. For example, the lectures in the universities could be given by actors; the professors speak like they’ve got mush in their mouths, anyway. And you could profit from that to learn how to speak a text, too, how to read it. It’s not just the conclusion you reach when you come to the end of Descartes’ sixth Meditation that counts, or having to be able to talk about his system on an exam, but the time it takes to reach its conclusion, the distance you have to go – in other words, the experience lived in learning about Descartes. I’m not saying this is the only thing that needs to be done; but, after all, when thousands of things need to be changed, I think you’d do well to try changing just one or two, instead of saying right off, once and for all, that it’s good or it’s bad.

Do actors, like movie-makers or technicians, need more study? Do they need more training?

Training, yes. The kind the American actors used to get. If I were giving a course for actors, I’d give them physical or intellectual exercises to do, nothing else. I’d tell them, “now you going to some gymnastics” or “you’re going to listen to this record for the next hour.” Actors have so many prejudices in physical and intellectual matters. For example, when we were making Deux ou Trois Choses, Marina Vlady came up to me one day and said, “What should I be doing? You never tell me.” So I told her – she lives in Montfort L’Amaury – I told her to walk to wherever we’d been shooting, instead of taking a taxi. “If you really want to act well, that’s the best thing you can do about it.” She thought I was putting her on, so she didn’t do it. I think I still hold it against her; just a little bit. She might have done it if I’d explained it all. But she’d only have done it once, and then the next day she’d be expecting me to come up with something else. So it just wasn’t worth explaining it. I wanted her just to think what she had to say. That’s all. Thinking doesn’t have to mean intellectualizing. If she was supposed to put a cup down on a table, I wanted her to think an image of a cup and an image of a table. Everything that’s involved in just walking to the location every day would have put her in shape to move and speak the way that would have been right for what I was trying to do. What I asked her to do was a lot more important than she thought, because to get to the point where you can think, you’ve got to do a few simple things just to get yourself into shape. Everyone knows that a dancer can’t dance unless he trains himself for it every day, does his exercises. But the idea that actors need “exercise” too was already on the decline among the actors in theater. Film actors haven’t the slightest idea of what kind of exercises they ought to be doing. They tell themselves that since they don’t have to kick up their legs there’s just no point in exercise. Before shooting started on La Chinoise, I asked Jean-Pierre LCaud to eat. I gave him the money – I told him he couldn’t spend it over at the Cinémathèque – just so he’d be eating a meal, in peace and quiet, ninety minutes a day every day, not reading the paper, not doing anything but eating an ordinary meal in an ordinary restaurant. That’s what he needed to do for La Chinoise. Exercises like these are a little like a reverse yoga. It’s the kind of thing the surrealists used to call “practical exercise.” They are needed in every activity, on every occasion. Actors don’t seem to remember they’re being paid for eight hours of work a day. Just like factory workers. The thing is, as soon as the worker reaches the factory he works – a full eight hour day; he can’t cheat. Actors can and they do like a lot of others in the white-collar professions. An actor doesn’t work an eight-hour day – if only because you can’t shoot eight hours straight. All I ask is that he do more work between the takes and less during them. Because, if he’s done his work before the take, I can be sure it’ll be good. It doesn’t do any good if he has to do his work during the take. The trouble is that it’s the hardest thing there is to get an actor to do. But even so, when we were making La Chinoise they got along pretty well. They worked well as a group; together they did just the right kinds of things to keep them in pretty good shape for shooting. It went a lot smoother than Masculin-Féminin. Obviously, now, every thing I’ve been saying applies to professional actors as well. Neither the professionals nor the nonprofessionals are prepared to submit to the slightest training. Anna Karina’s like all the rest on this point. I kept telling her, all I wanted her to do was, every day, read the editorial in the paper, Le Figaro or L’Humanité, aloud, calmly. She didn’t understand either. Even though little things like this have a direct influence on one’s acting. It’s exactly the equivalent of walking for an athlete, scales for a pianist, limbering-up exercises for an acrobat. The big problem with actors in film is that they’re often so very proud. So, they’ve got to be taught to be humble, the way the humble have to be taught to be proud. It’s as Bresson says, “give and receive.” And from this point of view, I see no difference between the professionals and the nonprofessionals. There are interesting people all over the place. But Bresson talks about actors the way the Russians talk about the Chinese. I kept telling him, “They’ve all got eyes, mouths, hearts…” And he’d keep saying, “No!” If I’d said, “Well… when Jouvet was still in his mother’s belly…” he’d have said, “Oh well, you know… Predestination!”

There’s a much larger problem involved in these exercises you’ve prescribed: it’s a problem of education. For example, the characters in La Chinoise have all emerged from the bourgeoisie, which has given them the education they’ve begun to question.

The fact is, it all lies in the way they’ve gotten the knowledge they have. Their education is an education in class. The way they conduct themselves is determined by class; they conduct themselves like members of their class. That’s all made very clear in the movie, anyway. On the subject of this “education in class” that prevails here in France, here’s a thing I cut out of a paper the other day; I’m keeping it because I’d like to make a movie on Rousseau’s Emile. Missoffe – he’s our Minister of Youth, remember – is on record as saying – it’s in his White Book – and I quote: “The schools must translate the structure of society into its programmes: it must organize (1) a long and highly intellectual training for children appointed in the main by their family origins to the highest posts in the direction and administration of society; (2) a shorter and simpler kind of instruction for the children of workers and peasants, whose entry into the labor-force, it would seem, requires no more than a limited training.” No comment.

Tell us something about your Emile. What will it be?

A modern movie … The story of a boy who refuses to go to his high-school because the classes are always too full. He sets about teaching himself, on the outside. He observes people, goes to movies, listens to radio, looks at television. Education, just like film today, is an immense accumulation of techniques that need to be re-examined, corrected. Everything needs re-examination. What’s going to happen to the son of a workman who decides he wants an education? Right at the start, he’ll find himself in a jam for money. We always get back to the Third World’s problems. The whole system of scholarships is really immoral. They are supposed to go to those who “deserve” them. All right, who “deserve” them? Because the schools are recruiting right now, just like the army, and the kid who doesn’t answer the call just hasn’t the right to pass his exam, those who “deserve” them turn out to be the ones who always come to class, which means, then, the ones who can always afford to come, who don’t have to be working their way through school. Even if the ones who attend every class don’t necessarily learn any more than the ones who miss more classes than not. Then again, no one knows what to do to give people the desire or the time to learn. Then again, the teachers are so poorly paid! I don’t say it’s simple. I’m just saying that there’s much too much that’s totally unacceptable, right from the start.

Are you saying the problem has no solution?

No! Because, all the same, it’s nothing like it is in France in America, Russia, or even Albania. In the first place, they spend much more on education than we do. In France, the restrictions placed on funds are the result of deliberate policy. I refer you to Missoffe. And de Gaulle. He’s just finished telling the Canadians that “they had a right to form elites of their own.” There’s the whole government mentality, right there. Notice: he was careful to choose his words. He didn’t say, “You have a right to train teachers, more researchers.” No, he said, “elites of your own.” The thing is, they already have an elite. Quebec doesn’t need to be free to have an elite of its own.

In eastern-bloc nations, it’s much easier to get an education. But some kinds of training are still reserved for an elite. A thirty-year-old day-laborer can’t ever hope to make inovies. He’d have had to have been to film school.

The work a day-laborer and an intellectual doare quantitatively but not qualitatively different. We’ve never been placed on an equal footing, which is why we can’t say or do anything together. A worker… I have to repeat myself -a worker has nothing to teach me, nor I him. It ought to be just the opposite. There ought to be a lot I could learn from him and he from me, instead of its being me from my colleagues and he from his. That’s why some people today – the Chinese, let’s say, or, at any rate, some Chinese – want to change it. The hope of changing it isn’t utopian if you’re willing to reckon not on a few but on a few hundred years. Civilizamore tions last a long time. How can we expect the new civilizations that began with Marxism just a hundred and fifty years ago to be accomplished all at once? It’s going to take a thousand years, maybe two thousand.

As a matter of fact, the world’s last Cultural Revolution is just two thousand years old. It was the Christian revolution.

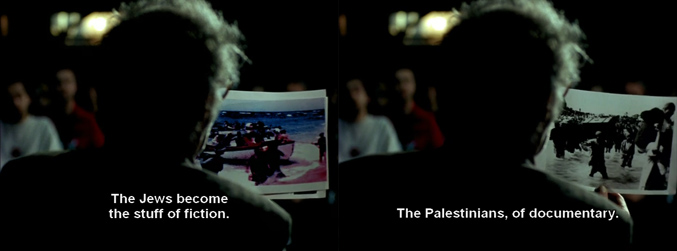

It’s only just starting to finish up. It’s produced nothing but reactionaries. The industries of image are still its most trusted mercenaries.