In the context of Courtisane Festival 2023 (Gent, 29 March – 2 April 2023). Curated by Stoffel Debuysere.

“For me, at the beginning of every film, there is always virtually nothing. You could carve this on my headstone. That is my conception of political cinema. Something can be done with even the most minuscule fragment of life; an ideal to be reconstructed. This supposes constant movement, an entire existence being on the alert. Staying face to face with the world, head held high, without trembling, no matter what.”

He liked the word ‘trajet’. The connotation of the English ‘trajectory’ was way too mechanical for him – alluding too much to the trajectory of a bullet, for example. For Kramer, the French word, on the other hand, sounded very much in tune with a human scale of movement, with the coming and goings, dwellings and wanderings that define most of our lives’ paths. A word that’s more than apt for a filmmaker who was always on the move. Whether by choice or necessity, he was always the traveller who, seemingly, never fitted anywhere – always looking for ways of living differently, following his taste for adversity and complexity. How could his films, then, be anything but the expression of this restless search?

Growing up, he lived in two worlds. As a doctor’s son, he was set in a comfortable scene. And even then, he was already an outsider. Wherever he looked seemed foreign to him. A mysterious fiction that had to be deciphered at all costs. He could never shed the feeling that a war was raging. “Survival is at stake,” he said, “and our dreams are the first to go.” For a while though, dreams were flaring up like flames. To Robert Kramer, the experience of the 1960s remained the touchstone for his life and work, the moment when his ‘trajet’ really took off: first as a journalist in Latin-America and a community worker in Newark, later as a filmmaker and a member of the Newsreel Collective. Again and again, Kramer sought out the battlegrounds: in Venezuela, Vietnam, Angola, but also closer to home, in the heart of the radical movements challenging the American political structures, which he portrayed so well in Ice (1969). Time and again, he found himself committed to the search for adverse communities, of which he himself depicted the breakdown in Milestones (1975): an unsettling portrait of his ‘lost’ generation.

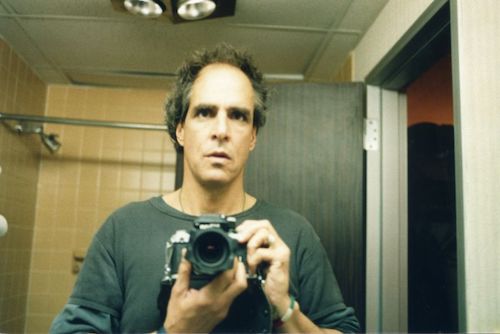

But filmmaking, for Kramer, remained. Filmmaking as yet another way of creating temporary communities to inhabit, the shelters and campsites that he so greatly needed. After moving to Europe in 1980, cinema would, more than ever, become his true habitat. Working from his base in Paris, he produced more than twenty films, varying in length, genre, medium and degree of achievement. Armed with his camera, Kramer not only kept on exploring the contours and edges of the world, but also of himself, as critical cartographer of a fast changing society, rebounding between private and public, interior and exterior, choice and necessity. The theme of ‘the return’ would become central to his work. The character of Doc, who first appeared in Ice played by Paul McIsaac, returns in both Doc’s Kingdom (1988) and Route One/USA (1989), which marked Kramer’s own return to the US after ten years of absence. Through this character, who is also his alter-ego, Kramer crafted diverging perspectives on his relation to what he left behind him, to that “what you are inevitably a part of and what you are forever outside.” He would also return to another ‘starting place’, the place that he first visited to make the Newsreel Collective’s People’s War (1969): Vietnam. In both Point de départ (1993) and Say Kom Sa (1998), he charts the country’s struggle through an uncertain and daunting past, present, and future. Yet another return would lead him to the city where his father was born, resulting in Berlin 10/90 (1990): an intimate dialogue with all the resonances that ‘Germany’ came to have, both in his family history and in global history.

Finally, the act of returning would also take the form of ‘feedback’, which was the original title of Notre nazi (1984). In this ‘behind the scenes’ film, Kramer ingeniously doubles up and problematizes the mise-en-scène of the film Wundkanal, with which its director, Thomas Harlan, attempted to exorcize a haunting past. But perhaps Kramer’s most personal form of feedback is Dear Doc (1990), a video letter addressed to his dear travel companion, in which he looks back on the creation of Doc’s Kingdom and Route One/USA. Returning, revisiting, going back – not home, but back: here’s the red thread running throughout this homage to a filmmaker whose ‘trajet’ is unlike any other.

——

Thanks to Keja Ho Kramer, Ricardo Matos Cabo, Céline Paini (Les Films D’Ici), Diana Vidrascu & Pip Chodorov (Re:Voir), Matthieu Grimault (Cinémathèque Française), Hugo Masson (Documentaire sur grand écran)

——

Route One/USA

Robert Kramer, UK, FR, IT, 1989, DCP, 255′, English spoken

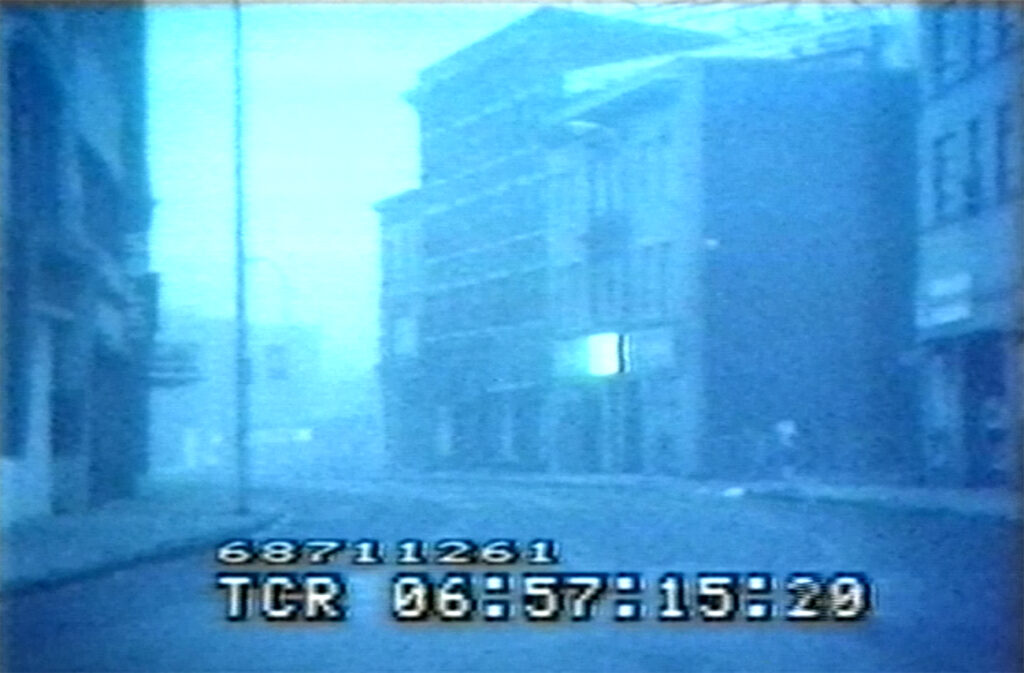

In September 1987, Robert Kramer returned to the US after a decade of self-imposed exile, where he spent five months filming along Route One, which connects Canada to Key West in Florida. In 1936, it was the most travelled route in the world, meanwhile it runs alongside superhighways and through suburbs – a thin strip of tarmac that cuts through all the old dreams of a nation. Together with fellow traveller Doc (Paul McIsaac), Kramer enters a succession of private worlds that steadily reveal themselves to the camera: from a Native American reservation in Maine to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington DC, from a Thanksgiving dinner at a homeless shelter to a sermon at an evangelical church. The grittiness of Kramer’s earlier militant work has given way to a casual mise en scène, with a fluid camera moving amidst ever-changing characters. Rarely did a filmmaker so fearlessly tread the fault lines between documentary and fiction, between inside and outside, to the point where the film almost breaks in half.

“There is a structure that is almost the same for all the films: you arrive in the middle of something, and lots of elements are given to you. It’s fragmentary, chaotic, you get a lot of signs, a lot of little things to work with. As you go along, it starts to fall into place. I think it’s a very accurate reflection of how my mind works. In the beginning, films are like a vast area, a geography. They are populated with people. Places are extremely important. And I don’t know where I’m going.”

——

Doc’s Kingdom

Robert Kramer, FR, PT, 1988, 35mm, 90′, English spoken

Twenty years after Doc first appears in Kramer’s film Ice, as the leader of a mythical underground revolutionary organisation played by Paul McIsaac, his character returns here as a disillusioned former activist who practices medicine as a way to stay true to his beliefs. After a stint in Africa, he ended up in Lisbon, where he divides his time between the local hospital and his lonely cottage on the docks. “Go home,” says the local café owner (played by filmmaker João César Monteiro). But Doc no longer knows a home. His past catches up with him when his son (a young Vincent Gallo) visits him from the US. A prelude to Route One/USA that draws inspiration from one of the filmmaker’s favourite books, Malcolm Lowry’s Under the Volcano, and reverts back to some of Kramer’s main themes: “the US, a home, a homeland, of which you are inevitably a part and of which you are forever outside.”

“I am very attached to the idea of geography. Most often, for me, places come before people. Starting with Doc’s Kingdom, what was an important formal idea was the idea of the trajet, a very beautiful word that doesn’t exist in English. It was this idea of filming bodies moving through spaces that interested me. I never liked travellings, very concretely: I couldn’t stand the idea of placing the rails. It seemed to me that it was an incredible pain to lay fifty meters of rails in order to accompany a character. The question was also: how to move in a space in a reasonable length of time, which does not become unbearable?”

Dear Doc

Robert Kramer, US, FR, 1990, video, 35′, English spoken

A video letter addressed to Kramer’s fellow traveller and accomplice, Paul McIsaac, aka Doc, the main character in Doc’s Kingdom and Route One/USA. This candid letter, written, filmed and composed after the editing of Route One/USA, expresses all the strength and density of a long-term friendship that would last.

“I’ve always been frightened of what you might call the Jonas Mekas syndrome, which means: ‘I totally embrace my subjectivity’. I had decided to go to the very end, I was going to say everything. Show everything, for once. And then, there’s every way to not even show what you thought you were going to show. I really wanted to reach another level. I wanted to do this by working twentyfour hours a day. You could also call it the Chris Marker syndrome. I was going to plunge into it completely. I wasn’t going to answer the phone, go home, and I’d see what would happen. What did happen is Dear Doc.”

——

Point de départ (Starting Place)

Robert Kramer, FR, 1993, 35mm to digital, 90′, French, English and Vietnamese spoken, English subtitles

More than 20 years after People’s War, which shaped his commitment against US war policy, Kramer returns to his starting point: Vietnam. “This was,” says Kramer, “what I knew, what I was interested in, what I was most invested in, where I had already made another film. I wondered how they could see things there: having paid such a price, being given the chance to participate in the New World Economy at gunpoint on the terms of the New World Order. It was either that, or disappear into oblivion, like Cuba.” Point de départ is an attempt to connect an immutable past with an irrefutable present. In Hanoi, despite economic transformations, the revolutions of the past half century live on in the memories of those who lived through them, people such as Kramer’s former guide from 1969, who has since translated Don Quixote, or a tightrope walker in the national circus who balances away the ghost of lost hope, or a man who took photos of B52s and another who lost his fingers shooting them down. But also activist Linda Evans, who was part of the crew that filmed People’s War and was sentenced to 40 years in prison in 1985. “You can see my film as a mourning process for the ideas that put Linda in prison. My ideas are in prison.”

“Many of the ideas that some people died for have been forgotten. It is necessary to read through the pages of recent history. The ‘starting place’ is really after the film. It is now. I could have made this film in another place. The most important thing was not to talk particularly or exclusively about Vietnam, but was, above all, this idea of ‘starting place.’ Because that’s the way things are, we have to start out from a look at what we have experienced over the last thirty years.”

Say Kom Sa

Robert Kramer, FR, 1998, video, 19′, French spoken, English subtitles

In 1997, Kramer visited Vietnam for the third time and shot this film, concluding his ‘Vietnam Trilogy’. His DV camera observes the accelerated transformation of society into the free-market capitalist system and the things that are about to be forgotten and lost in the process. The intimate travel diary turns into a deep meditation on globalisation and the filmmaker’s point of view.

“In the apartment, there are gifts from old friends in Vietnam: reminders of a different history. But the time is now, 1998: The ‘market economy’, that’s our common fate. A constructionsite on the edges of ‘West lake’ in Hanoi. This lake in the centre of Hanoi is being gradually walled in by huge modern hotels. The village ist disappearing. Everybody knows: It’s just a matter of money now. Who’s rich and who’s poor, who can and who can’t. That is how it is: ‘C’est comme ça …’ ”

——

Berlin 10/90

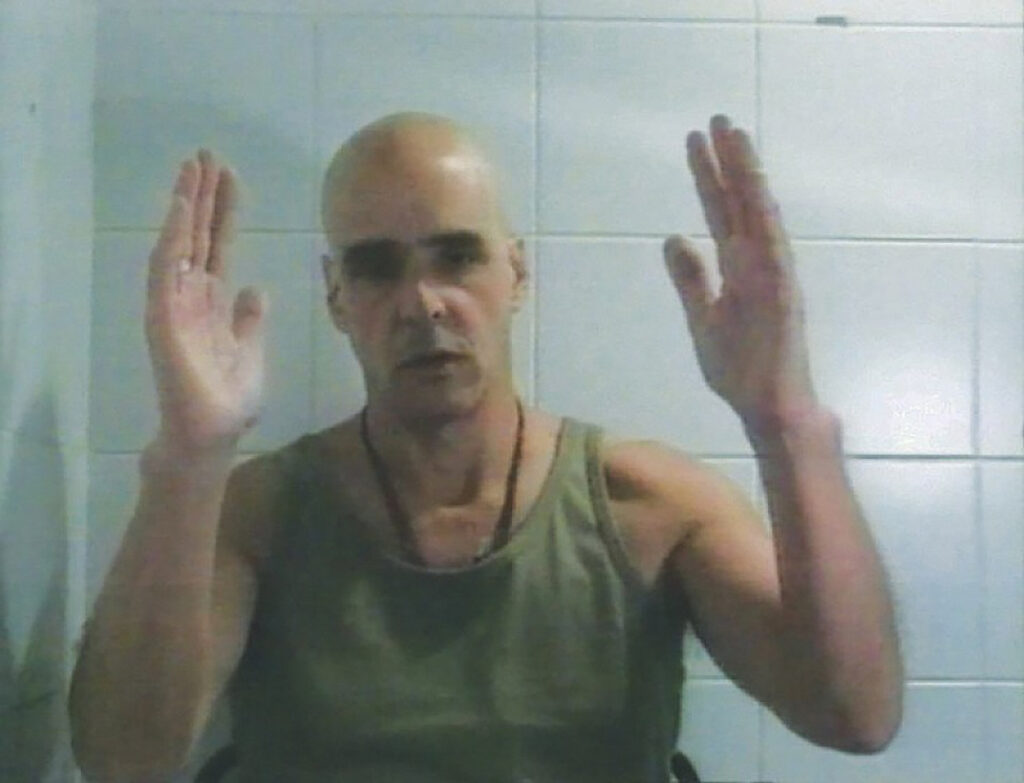

Robert Kramer, US, FR, 1990, video, 64′, English spoken

This film is part of the television series Live, curated by Philippe Grandrieux, conceived as a series of 14 episodes, each consisting of a single 60-minute long take, filmed on Hi8 video, without additional text, sound or post-production. Kramer’s contribution was shot in Berlin, his father’s birthplace, on 25 October 1990. Seated in the bathroom of his flat, he dialogues with images of the fall of the Berlin Wall and the Gulf War, and confronts his own hauntings. “Berlin has a lot to do with that idea of returning, going back to my father and a certain idea of the family past,” he says.

“They called this TV series Live, and it was offered up with a lot of oldsounding words what came out of the period of ‘Cinéma Verité’ or ‘Direct Cinema.’ Throughout there was the assumption that a camera running continuously can somehow access ‘the real.’ I don’t think that I realize how much I was moving in another direction or for how long. I was, for better or worse, involved in a very complicated dialogue between myself thenandthere in Berlin, and the many different connections that I have, inevitably, with Germany. You could say, a dialogue between myself and the reverberation that ‘Germany’ has become.”

Les yeux l’un de l’autre (I’ll Be Your Eyes, You’ll Be Mine)

Keja Ho Kramer & Stephen Dwoskin, US, FR, 2006, video, 47′, English spoken

A poetic ode that takes on the narrative framework of an afterthought: a detective, Keja Ho K., goes in search of a phantom, Robert Kramer. Together with Stephen Dwoskin, with whom Kramer exchanged video letters for years, Keja Ho creates an imaginary dialogue based on images from Kramer’s archive, fuelled by numerous memories and imbued with everything that would be close to his heart: the act of sharing, and the obligation to think for ourselves and to never betray our dreams.

“Working on I’ll Be Your Eyes, You’ll Be Mine was a way of being with you in the splendor of all the contradictions… it was also my relationship to the world, a reflection on how we work and take a point of view, try to be in the world in our own way. I met a wonderful friend of ours on this trip, Steve Dwoskin. I wanted to tell you how important this sharing with Steve was for me and how amazing it was to enter into the arrangement of ‘parts and pieces’ with him. Feeling this great connection in the work… the world of metaphor and symbolism, sculpting images, working with pixels as pigment, extensions of thought seeping into the computer canvas; amazing minds breaking through boundaries. How can I express how grateful I am to be on this walk, how sweet it has been (and always will be) to have known you and to have benefited so fully from your marvellous gift… Oh, Dad, you gave us so much freedom, and how hard that responsibility is… ”

——

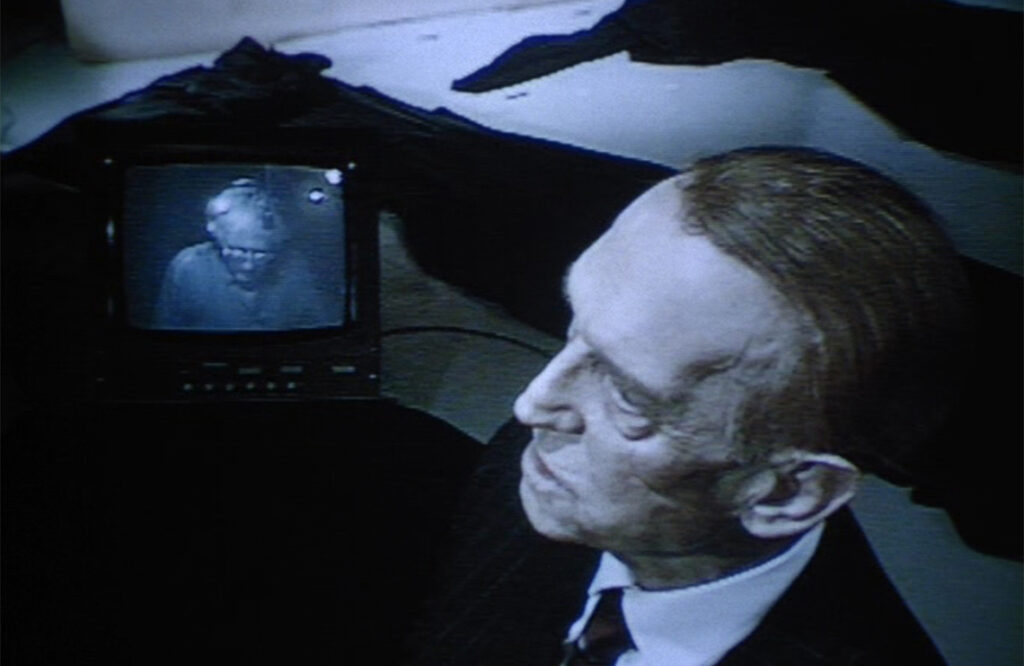

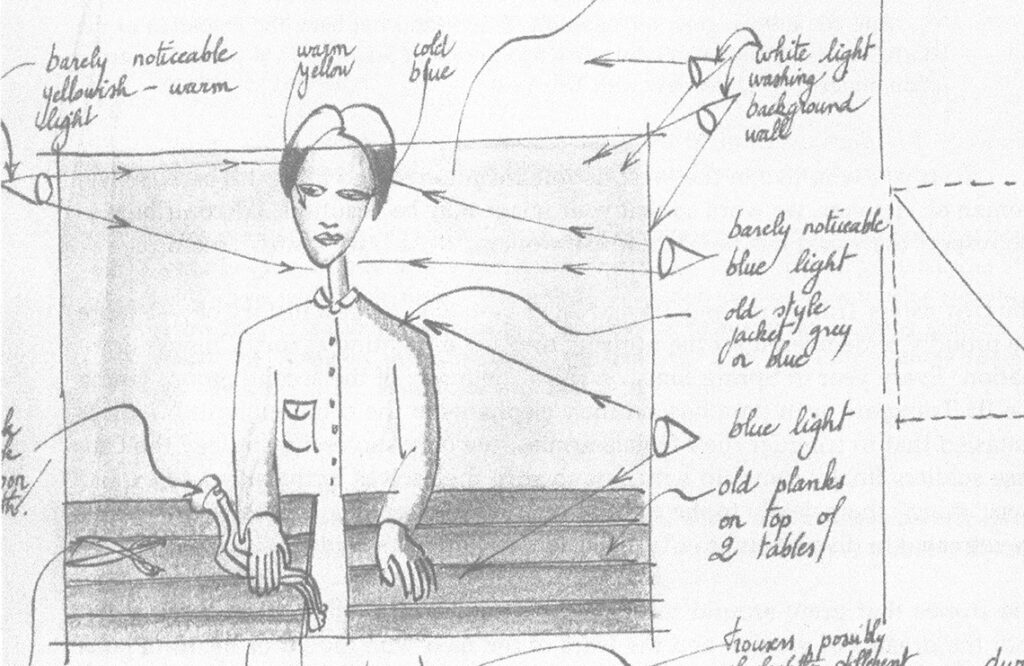

Notre nazi

Robert Kramer, DE, FR, 1984, video, 114′, English spoken

This gripping portrait was shot during the filming of Thomas Harlan’s Wundkanal, in which Alfred Filbert, a former Gestapo officer, plays an ex-Nazi kidnapped by a terrorist organisation. Kramer observes how Harlan – whose father, Veit Harlan, directed the infamous anti-Semitic propaganda film Jud Süß – gradually adopts the enemy’s methods in an attempt to come to terms with his past. Thus becoming, as it were, his own worst enemy. It is the story of two German generations, and also of an observant outsider, Kramer, who didn’t experience any of that history but said he felt connected to it in an abstract way through his Jewishness. He himself labelled the film “a really alive attempt to get inside an enigma.” With his camera, Kramer approaches and stalks Filbert as an unbreakable and opaque block of history that seethes at the centre of the dark film studio and of everyone’s attention. “My film is perhaps another fiction: the story of a certain T., son of the greatest Nazi filmmaker, and himself a film director. All his life he has tried to undo his past. Today he is shooting a fiction film, he has given the main role to a Nazi war criminal who is more or less the same age. By this act T. releases a whole torrent of unforeseeable energy which sweeps the set and even more than the set.”

“For me, the film is fundamentally about the question of judgment, about the complexity of a situation. On the one hand, we have Veit Harlan’s son, obsessed with his past and having such an understandable need to disassociate himself from that past and confront it within himself. It shakes up this strangely solid and integrated old man, who we know from the start is guilty of the worst we can imagine. And me, once again, an involved observer on camera. The film goes down some paths that lead nowhere. I’m not sure any of them lead anywhere. But they all revolve around the question of judgment: who has the right to judge? What are the right ways to judge?”