Publication compiled and published on the occasion of the film programmes dedicated to Ogawa Shinsuke and Ogawa Pro (CINEMATEK Brussels, 1 April – 5 May 2019) and Tsuchimoto Noriaki (Courtisane Festival Ghent, 3 – 7 April 2019). Both programmes, initiated by Courtisane, would not have been possible without the dedication of Ricardo Matos Cabo.

Ogawa Shinsuke (1935-1992) and Tsuchimoto Noriaki (1928-2008) are considered as the two towering pillars of Japanese documentary film. Both filmmakers forged parallel trajectories through the tumultuous landscape of postwar Japan, during which they developed extraordinary forms of committed cinema which remain unequalled in their dedication and perseverance.

Ogawa and Tsuchimoto were among a number of crucial postwar Japanese filmmakers who emerged from Iwanami Productions, a studio run by the Iwanami publishing house that mostly produced educational and PR films. Heated discussions on cinema and politics amongst these filmmakers led to the creation of an informal group they called the “Ao no kai”, or “Blue Group”. When the group dissolved, Ogawa and Tsuchimoto each went on their own way to make their first important independent films, which took sides with the student protest movement in Japan in the mid to late 1960s.

In the years that followed, their filmmaking approach underwent a profound transformation, which can be described as a movement from “outside” to “inside”. This inward shift, which evolved towards a full implication in the struggles of the people they filmed, reached its most refined and profound development in the Minamata and Sanrizuka Series. While Tsuchimoto committed himself to document the disastrous consequences of the mercury poisoning incident in Minamata, Ogawa recorded with great diligence the struggle by farmers and student protesters to prevent the construction of the Narita International Airport in Sanrizuka.

After the waning of the Sanrizuka protests, Ogawa and his colleagues of Ogawa Productions devoted themselves to an equally ambitious project, relocating to Yamagata Prefecture and beginning a series of films focusing on the rural village of Magino. Living and working with the farmers they filmed, the collective created a unique portrait of a culture and a way of life that are rarely depicted. From his side, Tsuchimoto – and his crew – continued to painstakingly document the effects of the Minamata tragedy on the life of the local fishing communities, while also redirecting their focus towards the dangers of nuclear power and the “theft of the sea” perpetrated by giant business conglomerates.

With the benefit of hindsight, the films of Ogawa and Tsuchimoto reveal themselves as monumental works in progress which remain open to incessant processes of debate and development. They made films that convey a material understanding of the world they document, films not on a subject, but with the subject. The astonishing commitment and persistence invested in their work continues to raise timely and pertinent questions about the responsibility, politics and ethics of documentary

filmmaking in the face of injustice and adversity. In that way, their films still accomplish what they were meant to do in the first place: to cultivate shared spaces of collective thought and struggle.

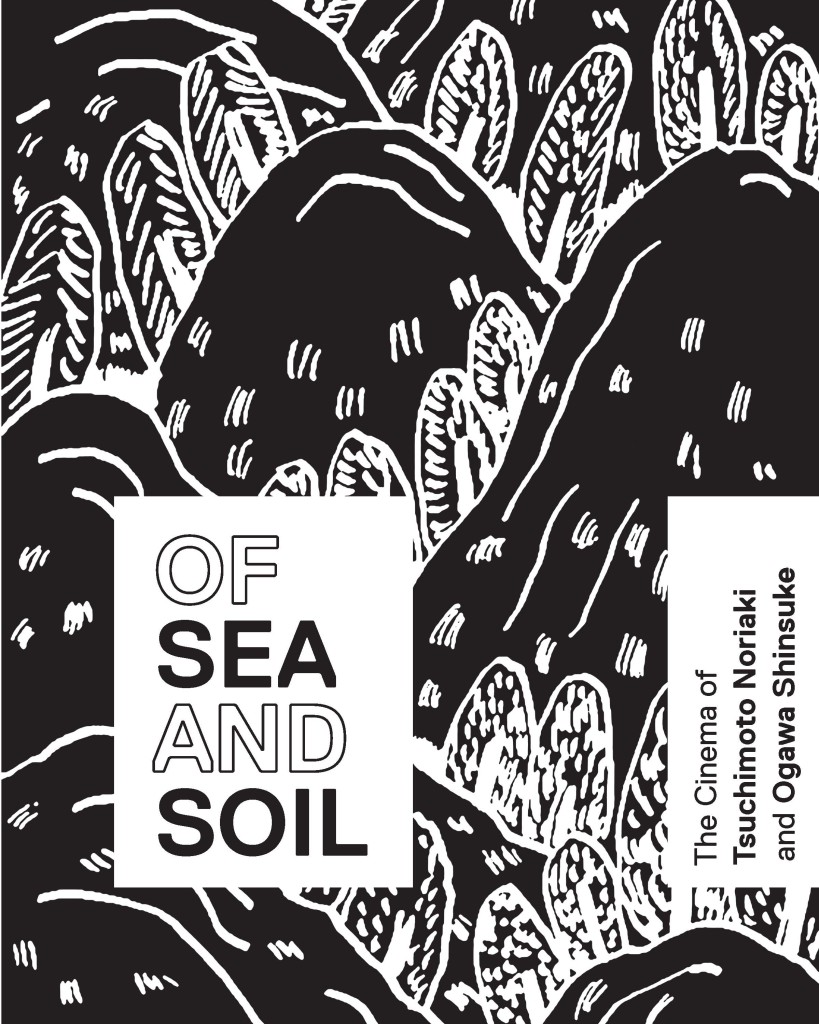

This publication aims to trace the trajectories of Ogawa Shinsuke and Tsuchimoto Noriaki, who film critic Hasumi Shigehiko respectively called “the filmmaker of the soil” and “the filmmaker of the sea”. The publication has taken the form of a scrapbook which assembles a patchwork of writings, quotes and interviews that we were able to track down and translate, with the help of numerous other “amateurs” who admire and cherish the work of these two filmmakers.

In all its modesty, we dearly hope that this body of texts, most of which are available here for the very first time in English, can serve as a stepping stone to a wider recognition and appreciation of these unique and singular practices of filmmaking which never cease to inspire and actuate.

Stoffel Debuysere, Courtisane

Elias Grootaers, Sabzian

Publication available via Courtisane bookshop