“If creativity is a field, copyright is the fence”

– John Oswald

What came before: Part 1

Here are some more historical and contemporary examples of explicit musical appropriation, as a sort of illustration or extension of a little article I wrote for RUIS , about music and creativity in the era of intellectual property. This is just a subjective selection, as you all know there’s much, much more out there. Sure enough practices of appropriation and “remix” are as old as creation itself, but have intensified over the past decades. As Willian Gibson notes: “our culture no longer bothers to use words like appropriation or borrowing to describe those very activities. Today’s audience isn’t listening at all – it’s participating. Indeed, audience is as antique a term as record, the one archaically passive, the other archaically physical. The record, not the remix, is the anomaly today. The remix is the very nature of the digital.” Paul Miller aka DJ Spooky: “Yes, the use of technology in the process of recreation generated a culture of the remix. With the conversion of all media to digital format, the distinction between the thought (or content) and the form (insofar as that form is digital media) becomes irrelevant: both have collapsed to the bit and byte, and thus, copyrighted as data.”

Dennis Duck, one o’clock jump, 1977

[audio:Dennis_Duck-oneoclockjump.mp3]

Dennis Duck was one of the members of the notorious Los Angeles Free Music Society (LAFMS), a loose collective of musical oddballs active in the Los Angeles of 1970-1980, who revelled in aesthetics based around radicalism and playfulness, exploring and mutating elements of musique concrete, free jazz, noise rock and the Dada attitude of Freak Out-era Mothers and Captain beefheart. As well as producing records, LAFMS held Fluxus-style concerts and happenings and published magazines (all this is wonderfully documented on the Lowest Form of Life 10CD box set, published by the Cortical Foundation). Key players included Joe Potts, Tom Recchion, Joseph Hammer, John Duncan, Juan Gomez, Kevin Laffey, Chip Chapman, Fredrik Nilsen, Jerry Bishop, Ace Farren Ford and Rick Potts. Dennis Duck was one of the most active members, who would later go on to play with The Dream Syndicate (with Steve Wynn) and Human Hands. In 1977 he released Dennis Duck Goes Disco as a hand-made cassette, in an edition of 20, who were mainly handed out to friends. The album was made entirely with a phonograph and records, utilizing skipping and pitch changes for most of the effects. Not an entirely new procedure (see previous post), but the refreshing thing was that Duck, with his skills as a drummer, combined with an understanding of concrete sound and improvisation created a drum machine out of his record player. To quote Rick Potts: “Dennis Duck did it! He captured the Genie in the bottle. Mr. Duck spun the wheel, rolled the tape and snared the unrepeatable magic of spontaneous sound. Dennis got friendly with a sensitive phonograph and they hit the jackpot to create a musique concrete masterpiece. This sort of thing is a science of skill, balance and chance. All factors fell into place and the result is this collection of serendipitous surprises. Mere recorded skips had transcended into miraculous chance compositions. Each track is increasingly sophisticated as Duck and machine become one, building with complexity until Dennis Duck zooms right past Disco and into Techno beyond!”

available on the reissue ‘Dennis Duck Goes Disco’ (Poo-Bah, 2007)

Ju Suk Reet Meate, untitled, 1978-1979

[audio:JuSuk_06.mp3]

Another member of LAFMS, whose stuff recently surfaced again (as well as playing live again). Ju Suk Reet Meate (pronounced as “You secrete meat”) is probably most well known as member of Smegma, but his solo outings, dating back to the end of the 1970’s, are really exciting as well. This track is one of the gems he recorded in 1978 – ’79, which were pressed in miniscule quantity in ’80. Someone described his music strikingly as “a post Zappa, stoned blues / concrete melange of guitar, tapes, found sounds and voice”. Highly recommended.

available on the reissue ‘Solo 78/79 ( aka Do Unseen Hands Keep You Dumb?)’ (De Stijl, 2007).

Richard Trythall, Omaggio a Jerry Lee Lewis, 1979

[audio:Trythall_OmaggioaJerryLeeLewis.mp3]

I don’t know much about the work of Pianist-composer Richard Trythall (1939), but this piece certainly is intruiging. It was composed in 1975 as the fourth in a series of musique concrète works. Just like Tenney’s “Collages”, it was created solely through tape manipulations, applied to Jerry Lee Lewis’ ‘Whole Lotta’ Shakin’ Goin’ On’. The material was first cut into thematic and motivic units of various types and sizes – words, phrases, notes, chords, musical fragments, etc. These were then subjected to a wide variety of procedures (speed change, filtering, head echo, reverberation, looping, signal interruption through erasure and excerpt loops, compression, expansion, phasing, panning, multiple readings, tape passes, editing, remixing, etc.). These results were then reassembled, mixed and re-mixed, until a new composition emerged. “The abstract idea was that, like the table or newspaper in a cubistic painting, the familiar musical object – here the Jerry Lee Lewis performance – served the listener as an orientation point within a maze of new material. The concrete result, so to speak, was that the studio manipulations amplified the source material, carried it into new, unexpected areas while maintaining its past associations. As in a dream, the material could present itself intact, then dissolve and reassemble in new, vaguely familiar shapes. Moving back and forth along this line, controlling this movement, was what fascinated me.”

available on Richard Trythall’s website

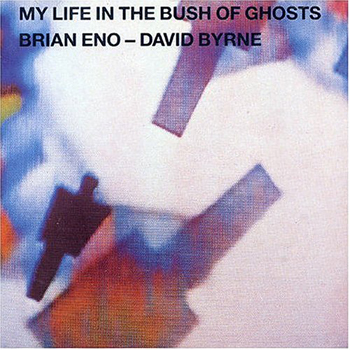

David Byrne & Brian Eno, Mea Culpa, 1980

[audio:Byrne_Eno_Mea_Culpa.mp3]

Dunno if this piece needs an introduction. It’s part of the classic My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, the album that Byrne and Eno recorded between sessions and concerts for the equally magnificent Talking Heads records Fear of Music (1979) and Remain in Light (1980). The project mailny grew out of Byrne’s and Eno’s fascination for the funk mutations of James Brown, Miles Davis (anno On the Corner), James chance and Fela Kuti, the experiments in dub and club music that were spicing up the NY avant garde music scene back then (Arthur Russell, for example), as well as the recordings of music from all over the world that were exchanged eagerly in that same scene. Inspired by this music they fantasized about making a series of recordings based on an imaginary culture. At that time Eno had also started to work on some recordings that incorporated found voices, partly influenced by Steve Reich’s experiments with tapeloops, as well as compositions such as John Adams’ Christian Zeal and Activity and Gavin Bryars’ Jesus Blood Never Failed Me Yet (see earlier post), both of which were released on his own Obscure label. In an interview he said “I’ve been working mostly in that direction, mostly taking radio voices because they’re easy to get hold of, and putting them to music . . . It satisfies a lot of interesting ideas for me. One is making the ordinary interesting, which I’ve always been interested in doing. The other is finding music where music wasn’t supposed to have been. And another is finding a pre-delivered message, which you put in a context so that the meaning is changed, or the context amplifies certain aspects of the meaning.” So Byrne and Eno invited some friends over and started to experiment with sounds and rhythms, using cardboard boxes as kick drums, bass guitars as rhythm instruments and basically anything that was lying around as a sound source. At that time there were no samplers, so found vocals were incorporated bu using two tape machines playing simultaneously, one containing the track and the other the vocal. Voices were “sampled” from recordings of various radio programs (the voices in ‘Mea Culpa’ were recorded from a radio call-in show in New York), as well as records of Paul Morton Dunya Yusin, a Lebanese mountain singer, The Moving Star Hall Singers and Samira Tewfik, an Egyptian popular singer. Byrne: “We continued to use ‘found’ vocals over rhythmic beds on My Life in the Bush of Ghosts … We hoped to emphasize the emotive force of the voice(s) as represented only by their sound and texture. For us, the emotion came across strongly … there was no need to understand in a logical or narrative manner what the words were about … the intense emotion carried by the quality of the voice, the melody, the rhythms, and the relationship of the vocal to the music (in two pieces we used almost the same bit of found vocal … against different music … and the effect was completely different). For us it was not only a good ‘idea,’ but an emotional experience.” The clearance of samples that Byrne and Eno sought was apparently a novelty:“no one knew what the hell we were up to.” The disk has faced at least two challenges on the grounds of the inappropriate use of the samples: the track ‘Qu’ran’, which features recordings of Muslim preachers chanting from the Koran (which Eno and company decided to leave off the recent reissue after complaints from the Islamic Council of Great Britain); and for the original version of ‘The Jezebel Spirit’, which was entitled “Into the Spirit World” and featured a recording of Christian preacher Kathryn Kuhlman, but was blocked by her estate and replaced by a recording of another preacher. The album was initially shelved, but in the meantime some of the songs were revised or left out all together. In 2006 the album was re-issued, featuring 7 previously unreleased tracks from the original album (and a video copy of one of the two films that Bruce Conner based on music from ‘My Life…’). In keeping with the spirit of the original album, Eno & Byrne offered for download all the multitracks on two of the songs, free to edit, remix, sample and mutilate.

more info on the My Life in The Bush of Ghosts website

This is a video of Conner’s film:

Douglas Kahn, Ronald Reagan Speaks for Himself, 1982

[audio:Kahn_reaganspeaks.mp3]

One of the most well known “political” audio mash-ups, based on an interview Bill Moyers did with Reagan (a ton more Reagan cut-ups can be found at the Ronald Reagan Translations page). Douglas Kahn (who has now made a name for himself as an academic, mainly thanks to his book Noise, Water, Meat: A History of Sound in the Arts) produced it using a razor blade and reel to reel player. The first version of his collage (completed before Reagan was elected) opened with the Reagan being made to say “I want to say I’m President. I want to live in the White House!” After he was elected, the intro was changed to, “For the first time in Man’s history, I uhhh, I’m President!” The first version was issued by Sub-Pop as part of a cassette compilation (#5) and got some attention on college radio. The second version was published on flexidisc in Raw No. 4,, as Kahn states “after a small skirmish with Evatone, who wanted the alternative comic magazine to obtain Reagan’s permission. As this would have, of course, been impossible, the record was eventually produced overseas.” It was also issued on a folk LP called Reaganomic Blues and included in a remix of a Fine Young Cannibals track. This form of détournement has become very popular nowadays. See, for example Chris Morris‘ Bushwacked series (see video), and work by Aaron Valdez and Lenka Clayton.

available on Douglas Kahn’s website

Double Dee & Steinski, Lesson 3: The History of Hip-Hop Mix, 1985

[audio:Steinski_lesson3.mp3]

No need to go into the history of hiphop here – you can read about that elsewhere or just listen to this amazing piece of cut ‘n ‘ paste by Steve Stein aka Steinski. He produced his first record – ‘The Payoff Mix’ – with engineer and studio wizard Douglas DJ Franco aka Double Dee in 1983, in response to a nationwide remix contest by Tommy Boy Records. A panel of ten judges—including Afrika Bambaataa, Shep Pettibone, Jellybean Benitez, and Arthur Baker—unanimously chose the mix as the winner. Within two weeks “The Payoff Mix” became a Top 10 request on urban radio nationwide, but the release never saw official status (because they never cleared rights) and was subsequently bootlegged countless times. The Payoff Mix became the first record in a series now known as The Lessons. Double Dee and Steinski followed up with cut-and-paste landmark ‘Lesson Two: The James Brown Mix’ en this ‘Lesson 3: The History of Hip Hop’. With these pieces, based on dozens of samples, they were one of the first succesful users of digital sampling tools: “When digital technology happened, Douglas and I, and obviously a number of other people, stumbled into it. All of a sudden, you could be referential by taking the thing itself. Instead of re-contextualizing it on your instrument in music as part of your own composition, you could then re-contextualize the piece by taking the actual piece and putting it in a new setting”. Stein says that when ‘Lesson 1’ first came out, they had difficulties clearing rights for the songs they used from the larger record labels. At that time, some didn’t even know how to charge for samples. It wasn’t until releases by succesful outfits such as De La Soul that a system was created (see article for more info on this). “It turned into, ‘Now you can’t clear it, because it’s wildly and prohibitively expensive, so only rich people can play. There is now a mechanism: If you can afford it, then definitely you’re online. But it’s strictly for basically one major label talking to another major label.” Since The Lessons, Steinski has produced a variety of tracks, that are all collected on last year’s retrospective : from his hip-hop narrative about the Kennedy assassination (originally a white-label promo, also issued as a Flexi-disk for UK music magazine NME) to ‘Nothing To Fear: A Rough Mix,” an hour-long mashup that was produced for Solid Steel/BBC London.

available on ‘What Does It All Mean? 1983-2006 Retrospective’ (Illegal Art)

Tom Recchion, The Perpetual Motion Clock, 1985

[audio:Recchion_The-Perpetual-Motion-Clock.mp3]

Ah, another LAFMS member, perhaps the king bee. Tom Recchion not only designed most of the artwork for LAFMS events and releases (he is now one considered of the top graphic designers in the music industry: he made album covers for Prince, R.E.M., Alanis Morissette – a man’s gotta live – and many others), he was also active in countless musical projects, such as the Doo-Dooettes and Paul Is Dead (both with Dennis Duck) and Extended Organ (alongside Paul McCarthy, Fred Nilsen, Joe Potts and Mike Kelley), playing just about every instrument he could get his hands on: guitar, pianos, found and invented instruments, tapes, keyboards, paper, fans, synths, radio, records and finally computer. By now he has gathered quite a reputation, after collaborating with the likes of Keiji Haino, David Toop and Oren Ambarchi, but it’s worth noting that his first solo album (the wonderful Chaotica) was only released widely in 1996, although all the pieces on it were composed at the end of the 1970’s and the beginning of the 1980’s. Most of his early work consists of sound collages of looped, manipulated, and extrapolated music by so-called “exotica” or “lounge” masters such as Esquivel, Martin Denny and Les Baxter. Recchion – “the loop king”, as Terry Riley called him once – improvised with prerecorded tape loops, records, cassettes, keyboards and a battery of effects to turn their orchestral pop into something positively otherworldly. To perform these pieces in live environments he used spools of tape which were looped about the audience on mounted reel-to-reel players interspersed with plug-in glowing fireplace logs. This track was first released as a limited edition cassette, and finally resurfaced on the Chaotica album. The box LAFMS: The Lowest Form Of Music contains even more of his delicious early solo stuff.

available on ‘Chaotica’, Birdman (1996)

The KLF, The Queen and I, 1987

[audio:KLF_queen.mp3]

Remember these guys? You might recall their anthem “What Time Is Love?”, which was a huge hit at the beginning of the nineties. You may also remember their notorious performance at the 1992 BRIT Awards, where they fired machine gun blanks into the audience and dumped a dead sheep at the aftershow party. Also noteworthy are their alternative art awards for the worst artist of the year and their stunt of burning one million pounds sterling. The KLF (also known as The Justified Ancients of Mu Mu (aka The JAMs), The Timelords and other names) never shied away from controversy. On the contrary. Their debut single (1987) was ‘All You Need Is Love’, based on samples from The Beatles’ ‘All You Need Is Love’ and Samantha Fox’s ‘Touch Me (I Want Your Body)’. Although it was declined by distributors fearful of prosecution, and threatened with lawsuits, copies of the one-sided white label 12″ were sent to the music press, receiving positive reviews. They later re-edited and re-released the track, removing or doctoring the most antagonistic samples. The album 1987 (What the Fuck Is Going On?), was released in June 1987. On the cover of the LP it stated: “All sounds on this recording have been captured by the KLF. In the name of Mu, we hereby liberate these sounds from all copyright restrictions, without prejudice.”Included was this song, which samples large portions of the ABBA’s ‘Dancing Queen’. The recording came to the attention of ABBA’s management and, after a legal showdown with ABBA and the Mechanical-Copyright Protection Society, the 1987 album was forcibly withdrawn from sale. They then underwent a pilgrimage to ABBA headquarters in Sweden and attempted to meet the group to persuade them to allow them to release the LP. The meeting failed and instead the KLF presented a Swedish prostitute with a gold disc. They then burnt most of the copies of the LP (see cover of band’s 2nd LP)in a farmer’s field (for which they were nearly shot at by said extremely angry farmer) and threw the remainder of the copies overboard on the return ferry journey home. Later they released a censored version of the LP with the samples removed, with instructions on how to recreate the original. Also check out their next single, ‘Whitney Joins The JAMs’, with samples of the ‘Mission: Impossible’ theme alongside Whitney Houston’s ‘I Wanna Dance With Somebody’ (Ironically, The KLF were later offered the job of producing or remixing a new Whitney Houston album).

Christian Marclay, Jimi Hendrix, 1988

[audio:Marclay_Jimi-Hendrix.mp3]

Christian Marclay has been experimenting, composing and performing with phonograph records since the seventies. His interest in records, both as objects and bearers of sound, is expressed through sculpture, performance, video and music. Marclay grounded upon Cage and Schaeffer, but focused even stronger on the concept of noise. As sculptor, the wearing (both natural and arranged) of vinyl still remains a basis for presenting and representing music. For example, he would cut up records, glue them back together, and let people walk on the records before he uses them. Footsteps is a ‘record’ of his, but not in the normal sense: 3500 vinyl records were used as flooring at an artexhibition for six weeks, packed in covers and then sold. In performance, he mixes a wide variety of records on up to 8 turntables, fragmenting, repeating, altering speeds, playing the records backwards, etc. Marclay is a pivotal figure in the so-called “turntablism” movement, alongside Otomo Yoshihide, Martin Tétreault and scratch masters such as Mix Master Mike, Q-Bert and many others. HE also played with likeminded souls such as John Zorn, David Moss, Elliott Sharp, Zeena Parkins etc. The album More Encores was originally released as a 10″ vinyl record on No Man’s Land (Germany) in 1988, composed entirely of records after whom each track is titled. ‘John Cage’, for example, is a recording of a collage made by cutting slices from several records and gluing them back together into a single disc. In all other places the records were mixed and manipulated on multiple turntables and recorded analog with the use of overdubbing. A hand-crank gramophone was used in ‘Louis Armstrong’. Other tracks are based on the music of Johann Strauss, John Zorn, Martin Denny, Frederic Chopin, Fred Frith, Arthur Ferrante & Louis Teicher, Maria Callas, Jane Birkin & Serge Gainsbourg & Christian Marclay, and, in this case, Jimi Hendrix. You may also want to check out the compilation ‘Records’, with rare recordings from 1981-1989.

available on ‘More Encores’ (CD-version was released by Chris Cutler’s ReR Megacorp).

Public Enemy, Night Of The Living Baseheads, 1988

[audio: Public-Enemy_Night_Of_The_Living Baseheads.mp3]

It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back was the first hiphop record that really shook my world, back when I was in high school. Even listening to it now, knowing what I know now (do I know more or less?), it’s still an intense, powerful piece of music, a showcase for the potential power of sampling. Fusing elements of free jazz, hard funk, even musique concrète, the producing team, Eric Sadler & Hank Shocklee known collectively as The Bomb Squad, created a dense, ferocious sound unlike anything that came before. They would use tape loops backed with live taps on a drum machine in place of the samplers that were typical of the time (the TR-808 f.e.). In this track for examples you can hear sampled beats and pieces from tracks by the Average White Band, the Bar-Kays, Dennis Coffey, ESG, the J. B.’s, Kool and the Gang, Sly & the Family Stone, the Temptation, Rufus Thomas, David Bowie, Kurtis Blow, and others (for an overview, see here). It was also around this time that sampling practices were more and more prosecuted. Biz Markie was convicted for sampling Gilbert O’Sullivan song. De La Soul was prosecuted for using a sample from the Turtles and had to pay 1,7 million dollars (=141,666.67 dollar per second. The judge said: “sampling is just a longer term for theft… anybody who can honestly say sampling is a sort of creativity has never done anything creative”). In the track ‘Caught, Can We Get a Witness’ Chuck D raps: “Caught, now in court ’cause I stole a beat / This is a sampling sport / Mail from the courts and jail / Claims I stole the beats that I rail (…) I found this mineral that I call a beat / I paid zero (…) They say that I stole this / I rebel with a raised fist, can we get a witness?”. In the mid- to late 1980s, hip-hop artists had a very small window of opportunity to run wild with the newly emerging sampling technologies before the record labels and lawyers started paying attention. But by the end of the eighties, no one paid zero for the records they sampled without getting sued. They had to pay a lot. In an interview Hank Shocklee said: “That’s when the copyrights and everything started becoming stricter because you had a lot of groups doing it and people were taking whole songs. Now you’re looking at one song costing you more than half of what you would make on your album. Public Enemy was affected because it is too expensive to defend against a claim. So we had to change our whole style by 1991.”

available on ‘Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back’

John Oswald, Dab, 1989

[audio:Oswald_Dab.mp3]

John Oswald has been on the forefront of the sampling movement for decades now. His 1975 track ‘Power’ married frenetic Led Zeppelin guitars to the impassioned exhortations of a Southern US evangelist (inspired by William S. Burroughs’ cut-up technique) years before hip hop discovered the potency of the same (and related) ingredients. In 1980, Oswald founded the Mystery Tapes Laboratory, which created unnamed, unattributed works on cassette, described as “little boxes of sonifericity specifically formulated for the curious listener. Available in your choice of aural flavors: subliminal, blasted, excerpted, repeatpeateatattttttedly, these cinemaphonically-concocted aggregates of trés different but exquisitely manifest, unprecedentedly varied festerings of audio quality fine magnetic cassette tapes are the best of whatever you’ve been listening for”. In 1985 he wrote the essay “Plunderphonics, or Audio Piracy as a Compositional Prerogative” in which he proposed to experiment with existing music. “All popular music (and all folk music, by definition), essentially, if not legally, exists in a public domain. Listening to pop music isn’t a matter of choice. Asked for or not, we’re bombarded by it. In its most insidious state, filtered to an incessant bass-line, it seeps through apartment walls and out of the heads of walk people. Although people in general are making more noise than ever before, fewer people are making more of the total noise; specifically, in music, those with megawatt PA’s, triple platinum sales, and heavy rotation. Difficult to ignore, pointlessly redundant to imitate, how does one not become a passive recipient?”. In 1988 he released of the Plunderphonics EP, with “plundered” tracks, based on songs by Elvis Presley, Count Basie, Dolly Parton and Stravinsky’s. For its time it was the most extreme example of sampling ever produced. Oswald: “Dolly experiences a sex change, Elvis gets a crazy new back-up band, and the other two go through some pretty wild changes.” In 1989, Oswald released an expanded version of the Plunderphonics album containing 25 tracks, each using material from a different artist. This track, a reworking of Michael Jackson ‘Bad’, was on it. The album was praised worldwide. David Toop called it “recreational savagery”. Van Dyke Parks wrote: “The hits keep coming! Thank you for including me among those sure to admire your music. At any speed I remain yours in admiration”. A few months later however, Oswald received notice from the Canadian Recording Industry Association on behalf of Michael Jackson that all undistributed copies of the album be destroyed under threat of legal action as of Xmas eve ’89. “They insisted I quit playing Santa Claus,” Oswald observed. He sent out a press release, stating: “I wasn’t selling the disc in the stores, so I let listeners tape it off the radio for free,” explains Oswald, who paid for the production and manufacture of the CD out of his own pocket. He receives no royalties or financial compensation for airplay. Brian Robertson, president of CRIA said, “What this demonstrates is the vulnerability of the recording industry to new technology…All we see is just another example of theft.” Also check out the Rubáiyát EP, Plexure (1993), “the most extreme example of electroquoting, backmasking, sonic morphing, pop information density, & samplephobic scare tactics yet” and the GRAYFOLDED project, commissioned by the Grateful Dead, featuring interpolations of six dozen concert versions of the Dead’s symphonic ‘Dark Star’.

available on John Oswald‘s website

The Loop Orchestra, Romance, 1988-1990

[audio:Loop_Orchestra_Romance.mp3]

The Australian Loop Orchestra is, like Tom Recchion, another act who experimented with tape loops on reel-to-reel tape machines in the 1980’s. “The genesis of The Loop Orchestra occurred in the ashes of a simple two-tape-machine-no-man-band, The Nobodies, which died in a fire in 1980. From those ashes, and with a pastiche taken from the likes of Terse Tapes, home of seminal Australian Industrial outfit Severed Heads, an ashen poultice was formed to take up further and more involved household heretical experimentation, this time with reel-to-reel tape machines. This idea was subsequently expanded upon in the studio of Sydney radio station 2MBS-fm amid a group of experimental radio programmers. Two, John Blades and Richard Fielding, were using the studio equipment as an instrument, experimenting with tape machines through processes involving cutting, dissecting, rearranging and rejoining prerecorded tape, creating tape loops and playing them back. They felt a need to formalize their studio experimentation and so conceived the idea of creating a full blown machine orchestra. The intention of the Orchestra was for groups of instruments of an orthodox orchestra to be represented by reel-to-reel tape machines playing loops of the instruments’ sounds. In 1983 an ensemble comprising 4 reel-to-reel machines playing slowly evolving tape-loop constructions, made its live debut playing a live-to-air performance in the studio of Sydney radio station 2MBS-fm in 1983, as The Loop Orchestra.” It would take them 7 more years to finally release their first album (although they relaesed some stuff on an obscure cassette called The Men Of Ridiculous Patience). Recorded over the years 1988 – 1990 at Endless Studios, Suspense features three tracks that deconstruct and reconstruct soundtracks drawn from suspense and horror films of the 1930s through to the 1980s. A variety of eminent luminaries can lay claim to having been members of the Orchestra, including Patrick Gibson, Peter Doyle, Anthony Maher and Ashley Blower. The current lineup consists of John Blades, Richard Fielding, Emmanuel Gasparinatos, Hamish MacKenzie and Juke Wyat.

available on ‘Suspense’, Endless Recordings (1990). Subsequent records are available via quecksilber

The Tape Beatles, I’m Waiting + Waves of Waves, 1990

[audio:tapebeatles.mp3]

The Tape-beatles are a collaboration of varying membership that make music and audio art recordings,”expanded cinema” performances, videos, printed publications, and works in other media. They began creating works for audio tape in 1987. Their goal at first was to create a form of pop music that made no use of musical instruments, instead relying on tape recording and analog studio techniques as their sole source of sounds. In addition, the Tape-beatles aspired to an egalitarian attitude of artmaking, avoiding the use of “professional” equipment and milieux, opting instead to make work almost entirely using home stereo equipment. Furthermore, The Tape-beatles espoused the use of plagiarism as a positive artistic technique. Taking their cue mainly from musique concréte and cut-up technique, The Tape-beatles made analog tape recording and basic home stereo equipment, connected in unorthodox configurations. It was the Tape-beatles’ belief that such works constituted valid works of authorship in themselves, and, like Oswald, they never asked for legal permission to use other people’s work in their compositions. These pieces are form their second album, Music with Sound, which demonstrates a development from the crude musique-concrete techniques of their earlier work, making use of more sophisticated editing and mixing techniques. By grabbing infonoise from everyday living and presenting it in a new format, sounds take on new meaning.

available on ‘Music with Sound’ (Public Works Productions) The Tape-beatles catalogue is also available on Ubuweb

More stuff later…