In the context of the Courtisane Festival 2018 (28 March – 1 April, 2018). Curated by Stoffel Debuysere.

“I’ve sometimes been asked why I don’t have any thoughts or visions of a utopian country, a utopian world where everything will be good and we’ll all be good. I’d say that when you’re constantly confronted with the abomination of daily life, a paradox arises, since what we really have is nothing.

I do believe in something, and I call it ‘a day shall come’, and one day it will come. Well, probably it won’t come, because it has been ruined for us, for thousands of years it has always been destroyed. It won’t come, and I believe in it anyway. Because if I can’t believe in it anymore I can’t go on writing.”

— Ingeborg Bachmann

Es ist immer Krieg: haunting words borrowed from poet and writer Ingeborg Bachmann provide the subtitle for Annik Leroy’s newest film, TREMOR (2017). But the sentence also brings to bear a sentiment that runs through all of the work of this Brussels-based photographer and filmmaker: a sense of non-reconciliation, of refusing to resign oneself to the violences that permeate our daily lives. Leroy’s films remind us how histories of oppression and injustice keep on haunting the present, how their presence can not only be perceived in the scars ingrained in the physical landscapes that traverse contemporary Europe, but also reverberates in innumerable instances of violence and destruction that slip by with impunity. It’s those barely perceptible, brooding tremors that continually penetrate our everyday lives and interpersonal relationships, which can be felt throughout the films, videos and installations that Leroy has made since 1980; a variety of works that each in their own singular way encapsulate the words of Bachmann: “Here, in this society, there is always war, there’s no war and peace, there is only war.”

The dark passages of European history are always throbbing in Leroy’s work, starting with her first feature-length film, In der Dämmerstunde Berlin de l’aube à la nuit (1980), in which a solitary wandering through the old neighborhoods of the city of Berlin evokes a past of destruction and loss. Faceless ruins and deserted streets are the silent witnesses of a tragedy that has left a deep woundedness, one that finds resonance in fragments borrowed from the work of writers such as Gottfried Benn, Else Lasker-Schüler, Witold Gombrowicz and Peter Handke. Another journey filled with traces of the past, linking exterior to interior geographies, big to small histories, is recounted in Vers la mer (1999), this time following the Danube river from its source in Germany to its outlet into the Black Sea, connecting the soft landscapes of the Hungarian puszta to the borders with Vojvodina and Serbia, where turmoil and hatred raged along its shores. Over the course of many encounters, however, the river does not only reveal itself as a passive witness of an always present past, but also as an active force that, in its perpetual movement, comes to symbolise the organisation of a possible common space that defies boundaries and borders.

Leroy’s investigation into violence and oppression as structural moments of both the public and the private spheres is at its most radical in the short videowork Cellule 719 (2006). Taking as point of departure an letter written by Rote Armee Fraktion member Ulrike Meinhof when she was incarcerated in solitary confinement, the video probes the inner world of a woman who, in total isolation, is at the mercy of her most private self. The physical and psychic experience of violence and oppression is also what resonates in the voices that populate TREMOR – the voices of poets and madmen, of a mother or a child. Guided by the words and articulations of Pier Paolo Pasolini, Fernando Nannetti, Sigmund Freud, Barbara Suckfüll and others, the film takes us from Stromboli to Rome, from Vienna to Vestmannaeyjar, tracing a sensory journey through desolate and devastated wastelands that bring to mind the last images of Pasolini’s Teorema, in which we see a naked man howling across volcanic slopes: images of madness and anguish, but also of possible redemption. Not coincidentally, it is the vision of Pasolini that is brought to bear on TREMOR’s ending, evoking the prophetic dream of a life reborn beyond reason. An ending that epitomizes an essential undertaking in Annik Leroy’s poetics: to counter the continuing history of war and violence with an utopia that Ingeborg Bachmann has proclaimed as “a day will come”.

——

In der Dämmerstunde Berlin de l’aube à la nuit

Annik Leroy, BE, 1980, 16mm, b&w, 67′,

French & German with English subtitles

“Two years have passed since my first trip to Berlin. This month of October shows me the picture of my loneliness. I can still hear the sound of my footsteps on the Landwehrkanal, their crunching, and then the silence, the silence of a city. These empty roads, whose desolation confuses me; a moment of love imprinted on my memory.” Paris – October 1980

“With this film I try to retrace my journey, my story through the ruins, neighbourhoods, and streets of Berlin. I filmed the dialogue that took place between the city and myself, the wanderings in the old neighbourhoods (Moabit, Kreuzberg, Wedding), places where you can still find most of the traces of the past, or rather what’s left of them.” (AL)

“The feeling of finding oneself back in Berlin, a year later, to end a story. Searching for a past that no longer exists; an emotion in this city, which, the longer I walk around, increasingly resembles others, a city like any other … Bahnhof Zoo, to come back here, take the train to Paris, and start all over.” Berlin – November 1980

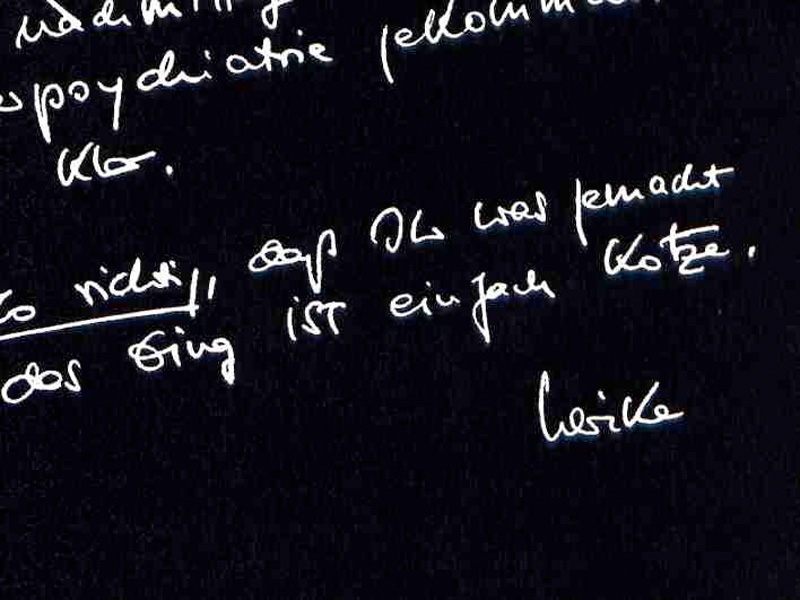

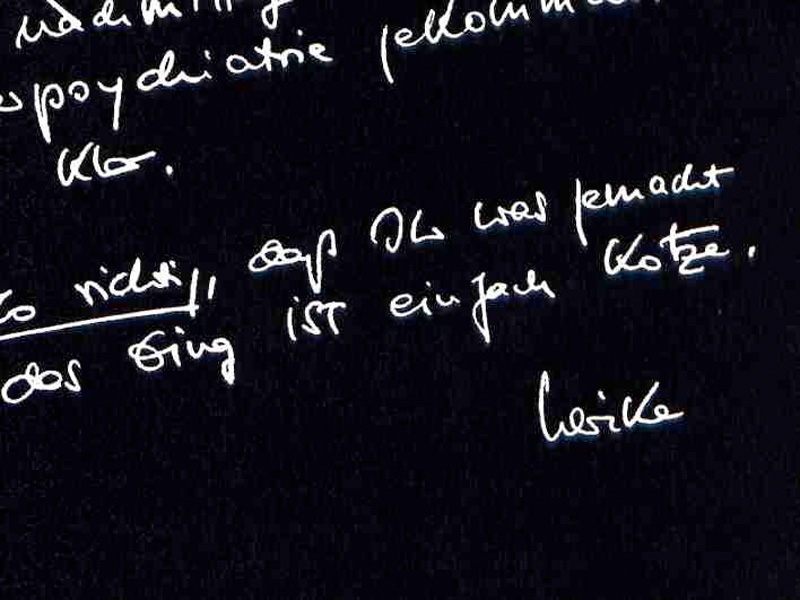

Cellule 719

Annik Leroy, BE, 2006, video, b&w, 15′

There is hardly any image in Cellule 719: from time to time we see a glimpse of water, but otherwise the film is mainly black. The texts that appear on the screen in grey are from ‘Ein brief Ulrike Meinhofs aus dem Toten Trakt’, a letter written in 1972 by the RAF member Ulrike Meinhof, when she was just imprisoned. For Annik Leroy, this video project is only an intermediate stop in a longer process, a study of the historical RAF and, even more so, into the psychological mechanisms of terror, and the personality structure of a public figure who is left alone in complete isolation with her most private self. (Edwin Carels)

“The feeling that time and space are encapsulated within each other—

The feeling of being in a room of distorting mirrors—

Staggering—

Afterwards, terrifying euphoria that you’re hearing something—besides the acoustic difference between day and night”

— Ulrike Meinhof, 1972-1973

——

Vers la mer

Annik Leroy, BE, 1999, 16mm, b&w, 87′, various languages with English subtitles

“Vers la mer is a documentary about and inspired by the Danube, the river of Mitteleuropa. The Danube, the only river of our continent that connects so many people as such a confusing mix. It is the route that links the West to the East, a myth as much as a reality, an epic towards the sea. A presence so strong, so dazzling, that it freezes the gaze and brings us back to a certain humility. A film that wants to situate itself between poetic reverie, historical and contemporary reality, encounters with those who live along the shores of the river. Will the river be the symbol of something else than itself?” (AL)

“Yet almost this river seems

to travel backwards and

I think it must come from

the East.

Much could

be said about this.”

— Friedrich Hölderlin, The Ister, 1803

——

TREMOR – Es ist immer Krieg

Annik Leroy, BE, 2017, 16mm, b&w, 92′, various languages with English subtitles

“Es ist immer Krieg is the subtitle of TREMOR. Four words. An extremely short sentence from Malina by Ingeborg Bachmann, which evokes many interpretations. But for me, they stand for inner conflict and not being able to reconcile with the wars of the past or present. There are no images recorded in conflicts here, because it’s up to me to create my own images. All fascist powers interpellate me; they challenge me, and ensure that I cannot be irresponsible.” (AL)

“Since long have I pondered the question of where fascism has its origin. It is not born with the first bombs, neither through the terror one can describe in every newspaper … its origin lies in the relations between a man and a woman, and I have tried to say … in this society there is war permanently.” — Ingeborg Bachmann

——

CARTE BLANCHE

Wanda

Barbara Loden, US, 1970, DCP, colour, 102′

“I believe there is a miracle in Wanda. Usually there is a distance between representation and text, between subject and action. Here, this distance is completely annulled. There is an immediate and definitive coincidence between Barbara Loden and Wanda … This miracle, for me, is not in the acting. It’s because she seems more truly herself in the film – I didn’t know her personally – than she could have been in life. She’s more authentic in the film than in life. That’s completely miraculous.”

— Marguerite Duras

The only feature film American actress Barbara Loden ever wrote and directed tells the story of a young woman adrift in rust-belt Pennsylvania in the company of a smalltime crook. “I made Wanda as a way of confirming my own existence,” Loden said. She described Wanda as a woman who “doesn’t know what she wants but she knows what she doesn’t want … life is a mystery to her, and she’s trying the best thing she can, which is just to drop out. A lot of people do this and they become very passive. We have this kind of person in our society who lets everything walk over them.”

Verj (End)

Artavazd Pelechian, AM, 1992, 35mm, b&w, 8′

Pelechian transforms footage from a train ride into a metaphor for the shape of life. Early images of faces on the train give way to landscape, a journey through a black tunnel, and a final emergence into pure white light.