By Jacques Rancière

A first version of this text was presented on the occasion of the award ceremony of the Maurizio Grande prize organized by the Circolo Chaplin in Reggio de Calabria in January 2004. The French text was published under the title ‘Les Écarts du cinéma’ in nr. 50 of Trafic and as prologue for the book with the same title (La Fabrique editions, 2011). Translated by Walter van der Star.

I did receive a prize once. It was the first, after leaving the lycée a long time ago. But the country that awarded it to me for my book Film Fables also happened to be Italy. This conjunction seemed to me to reveal something about my relation with cinema. That country had been important for my education in the seventh art in more ways than one. There was Rossellini, of course, and that one night during the winter of 1964 when Europe ’51 had blown me away even though I still resisted this trajectory of the bourgeoisie towards sainthood by way of the working class. There were also the books and magazines that a friend, a cinephile and lover of Italy, sent to me from Rome and from which I tried to learn about film theory, Marxism and the Italian language. And there was that strange backroom in a Neapolitan bar where, on some kind of crudely stretched bed sheet, James Cagney and John Derek spoke Italian in a dubbed black-and-white version of a film by Nicholas Ray called A l’ombre del patibolo (Run for Cover, for the sticklers).

If these memories came back to me when I received this unexpected prize, it was not simply for circumstantial reasons; and if I mention them now, it is not because of some sentimental trip down memory lane. It is because they present a fairly accurate outline of my rather singular approach to cinema. Cinema is not an object that I have delved into as a philosopher or as a critic. My relation with it is a play of chance encounters and gaps that these three memories will enable us to define. In fact, they typify three kinds of gaps* in which I have attempted to speak about cinema: between cinema and art, between cinema and politics, between cinema and theory.

The first gap, symbolised by the makeshift cinema where Nicholas Ray was being shown, is that of cinephilia. Cinephilia is a relation with cinema that is a matter of passion rather than one of theory. It is well-known that passion does not differentiate. Cinephilia was a blurring of accepted views. First, a blurring of places: a singular diagonal traced between the film clubs that preserved the memory of an art and out-of-the-way neighborhood cinemas showing a disparaged Hollywood film in which cinephiles could nevertheless discover treasures in the intensity of a horseback-chase in a western, a bank robbery or a child’s smile. Cinephilia linked the cult of art to the democracy of entertainment and emotions by challenging the criteria for the induction of cinema into high culture. It asserted that cinema’s greatness did not lie in the metaphysical loftiness of its subject matter nor in the visibility of its plastic effects, but in the imperceptible difference in the way it puts traditional stories and emotions into images. Cinephiles named this difference mise-en-scène without really knowing what it meant. Not knowing what you love and why you love it is, so they say, the distinctive feature of passion. It is also the way of a certain wisdom. Cinephilia explains its loves only by relying on a rather coarse phenomenology of the mise-en-scène as the establishment of a ‘relation with the world’. But it also called into question the dominant categories of thinking about art. Twentieth-century art is often described in terms of the modernist paradigm that identifies the modern artistic revolution with the concentration of each art form on its own medium and opposes this concentration to the forms of market aestheticisation of life. We then witness the collapse in the 1960s of this modernity under the combined blows of political doubts about artistic autonomy and the invasion of market and advertisement forms. The story of the defeat of modernist purity by the postmodernist attitude of ‘anything goes’ passes over the fact that in other places, like the cinema, this blurring of borders occurred in a more complex manner. Cinephilia has called into question the categories of artistic modernity, not by deriding high art, but by returning to a more intimate, more obscure interconnection between the marks of art, the emotions of the story and the discovery of the splendor that even the most ordinary spectacle could display on the bright screen in a dark cinema: a hand lifting a curtain or playing with a door handle, a head leaning out of a window, a fire or headlights in the night, glasses clinking on the zinc bar of a café… Thus it initiated a positive understanding, neither ironic nor disenchanted, of the impurity of art.

This was undoubtedly because cinephilia found it difficult to think the relation between the reasons of its emotions and the reasons that allow us to orient ourselves in the conflicts of the world. What relation could a student first discovering Marxism in the early 1960s see between the struggle against social inequality and the form of equality that the smile and the gaze of little John Mohune in Moonfleet re-establishes within the machinations of his false friend Jeremy Fox? What relation could there be between the struggle of the new world of the workers against the world of exploitation and the justice that is obsessively pursued by the hero of Winchester ’73 against the murderous brother, or the joined hands of the outlaw Wes McQueen and the wild girl Colorado on the cliff where the lawmen had followed them in Colorado Territory? In order to establish the link between them, it was necessary to postulate a mysterious equation between the historical materialism that gave the workers’ struggle its foundation and the materialism of the relation between bodies and their space. It is precisely at this point that the vision of Europe ’51 becomes blurred. Irene’s trajectory from her bourgeois apartment to the tenement blocks in the working-class neighborhoods and the factory first seemed to correspond exactly with these two materialisms. In the physical course of action of the heroine, who gradually ventures into unfamiliar spaces, the plot development and camera work is made to coincide with the discovery of the world of labor and oppression. Unfortunately this nice straight materialist line is broken in the short time when Irene climbs the stairs, finding her way to a church, and descends again, returning to a large-breasted prostitute the good works of charity and the spiritual path to sainthood.

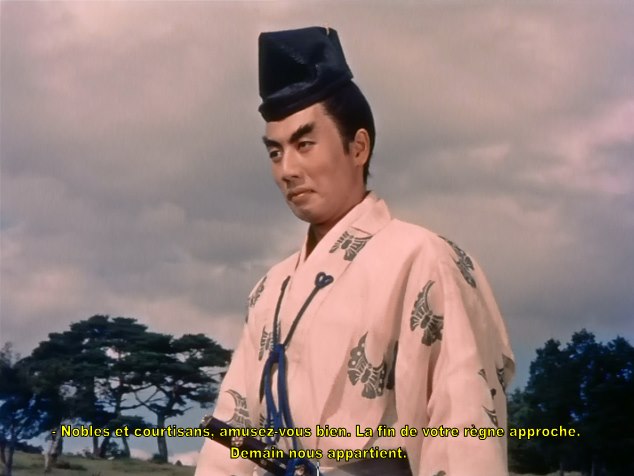

It then became necessary to say that the materialism of the mise-en-scène had been diverted by the personal ideology of the director. It is a new version of the old Marxist argument that praised Balzac for revealing the reality of the capitalist social world, even though he was a reactionary. But the uncertainties of Marxist aesthetics then double those of cinephile aesthetics by implying that the only true materialists are those who are so unwillingly. It is this paradox that seemed to be confirmed by my dejection at seeing Staroye i novoye (“General Line”), whose cascades of milk and multitude of piglets being weaned by an ecstatic sow had caused my aversion, just like they caused the sniggers of a movie theatre audience, most of whom, like me, probably sympathised with communism and believed in the merits of collective agriculture. It has often been said that militant films only persuade the convinced. But what if the quintessential communist film produces a negative effect on the convinced themselves? The gap between cinephilia and communism seemed to close only when aesthetic principles and social relations are foreign to us, like in the final sequence of Mizoguchi’s Shin Heike Monogatari (“New Tales of the Taira Clan”), when the rebellious son and his comrades in arms cross the prairie where his frivolous mother joins in the pleasures of her class and speaks these final words: ‘Nobles and courtiers, amuse yourselves while you may! Tomorrow belongs to us.’ The seductiveness of this sequence was undoubtedly due to the fact that it gave us a taste of both the visual charms of the doomed old world and the charms of the sound of words that herald the new.

How can we close the gap, how can we conceive the equation between the pleasure we take in the shadows that are projected onto the screen, the intelligence of an art, and that of a vision of the world – this is what we thought we could expect from a theory of cinema. But none of the combinations between the classics of Marxist theory and the classics of thinking about cinema have enabled me to decide whether climbing or descending the stairs is by nature idealist or materialist, progressive or reactionary. They never enabled me to determine what separated art from non-art in cinema, or to decide which political message was conveyed by an arrangement of bodies in a shot or a cut between two shots.

Perhaps it was necessary to reverse our perspective and ask ourselves about the unity between an art, a form of emotion and a coherent vision of the world that exists under the name of ‘theory of cinema’. We needed to ask ourselves if cinema does not exist precisely in the form of a system of unbridgeable gaps between things that have the same name without being parts of the same body. Actually, cinema is a great many things. It is the material place where we go to be entertained by a spectacle of shadows, although these shadows induce an emotion in us that is more secret than the one expressed by the condescending term “entertainment”. It is also the accumulation and sedimentation of those presences within us as their reality is erased and altered: the other cinema, which is recomposed by our memories and our words, and which, in the end, strongly differs from what was presented when it unspooled during projection. Cinema is also an ideological apparatus producing images that circulate in society, images in which the latter recognises the present state of its types, its past legend or its imagined futures. It is also the concept of an art, in other words, a problematic dividing line which, at the heart of productions of an industrial craft, isolates those productions that deserve to be considered as inhabitants of the large artistic realm. But cinema is also an utopia: a writing of movement that was celebrated in the 1920s as the great universal symphony, the exemplary manifestation of an energy animating art, work, and the collective. Finally, cinema can be a philosophical concept, a theory of the actual movement of things and thought, as it is for Gilles Deleuze, who discusses films and their procedures on every page of his two books, which are neither a theory nor a philosophy of cinema, but strictly speaking a metaphysics of cinema.

This multiplicity, which challenges every unitary theory, elicits different reactions. Some want to separate the wheat from the chaff: that which belongs to cinematographic art from that which belongs to the entertainment or propaganda industry; or the film itself, the sum of frames, shots and camera movements that are studied in front of the monitor, from distorted memories or added words. Such rigor may be shortsighted. Limiting yourself to art means forgetting that art itself only exists as an unstable limit that has to be constantly crossed in order to exist. Cinema belongs to the aesthetic regime of art in which the old criteria of representation that distinguished between the fine arts and the mechanical arts and confined them to their own separate place no longer exist. It belongs to a regime of art in which the purity of new forms has often found its model in pantomime, the circus or commercial graphic design. This means that if we limit ourselves to the shots and procedures that form a film, we forget that cinema is an art as well as a world, and that those shots and effects that fade in the instant of projection need to be prolonged and transformed by memory and words that give consistency to cinema as a world shared beyond the material reality of its projection.

For me, writing about cinema means taking two contradictory positions at the same time. The first is that there is no concept that brings together all these cinemas, no theory that unifies all the problems that they pose. The relation that exists between Cinema, the title shared by Deleuze’s two books, and the large theater of the past with red chairs where the news, a documentary and the main film were shown in that order, separated by ice cream during the intermission, is one of simple homonymy. Conversely, the other position states that every homonymy arranges a common space of thought, that thinking about cinema is what circulates within this space, exists at the heart of these gaps and tries to determine some sort of interconnection between two cinemas or two ‘problems of cinema’. This position is, if you will, that of the amateur. I have never taught cinema, neither the theory nor the aesthetics of cinema. I have come across cinema at different moments in my life: with the enthusiasm of a cinephile in the 1960s, as someone questioning the relations between cinema and history in the 1970s, or as someone questioning the aesthetic paradigms that were used to think about the seventh art during the 1990s. But the position of the amateur is not that of the eclectic who opposes the wealth of empirical diversity to the dull rigor of theory. Amateurism is also a theoretical and political position that challenges the authority of specialists by re-examining the way in which the limits of their domains are drawn at the junction of experience and knowledge. The politics of the amateur acknowledges that cinema belongs to everyone who, in one way or another, has explored the system of gaps that its name arranges, and that everyone is justified to trace, between certain points of this topography, a singular path that contributes to cinema as a world and to its knowledge.

That is why elsewhere I have spoken of ‘cinematographic fables’ and not of a theory of cinema. I wanted to situate myself in a universe without hierarchy where the films that are recomposed by our perceptions, emotions and words count as much as any other; where theories and aesthetics of cinema themselves are regarded as stories, as singular adventures of thought that have been induced by cinema’s multiple existences. During forty or fifty years, while discovering new films or new discourses on cinema, I have retained the memory of more or less distorted films, shots and phrases. At different moments I have confronted my memories with the reality of these films or called my interpretation of them into question. I saw Nicholas Ray’s They Live by Night again in order to relive the overwhelming impression made on me by the moment that Bowie meets Keechie in front of the garage door. I couldn’t find this shot because it doesn’t exist. So I tried to understand the singular power of suspension of a narrative that I had condensed into this imaginary shot. I have seen Europe ‘51 again twice: once to reverse my original interpretation and validate Irene’s sidestep, when she leaves the topography of the world of workers which was laid out for her by her cousin, the communist journalist, and passes over to the other side where the spectacle of the social world is no longer imprisoned in schemes of thought elaborated by the authorities, the media or the social sciences; and a second time to put into question the all too easy opposition between the social schemes of representation and the unrepresentable in art. I have seen the westerns of Anthony Mann again in order to understand what had seduced me: not simply the childlike pleasure of cavalcades across great spaces or the adolescent pleasures of perverting the accepted criteria of art, but the perfect equilibrium between two things: the Aristotelian rigor of the plot which, through recognitions and wanderings, brings everyone the happiness or misery they deserve, and the way in which the body of the heroes played by James Stewart, through their meticulous gestures, escapes from the ethical universe that gave sense to the rigor of the action. I have seen Staroye i novoye again and understood why I had rejected it so vehemently thirty years earlier: not because of the ideological content of the film, but because of its form: a cinematography conceived as an immediate translation of thought into a characteristic language of the visible. In order to appreciate this it would be necessary to understand that all those cascades of milk and litters of piglets were actually not cascades of milk or piglets, but the imagined ideograms of a new language. The belief in this language had died out before the belief in agricultural collectivisation. That is why I found the film physically unbearable in 1960, and perhaps why it took time to grasp its beauty and see it only as the splendid utopia of a language that survived the catastrophe of a social system.

On the basis of these wanderings and returns it became possible to define the hard core designated by the term cinematographic fable. First, this name recalls the tension which is at the origin of the gaps of cinema, the tension between art and story. Cinema was born in the age of great suspicion about stories, at the time when it was thought that a new art was being born that no longer told stories, described the spectacle of things or presented the mental states of characters, but inscribed the product of thought directly onto the movement of forms. It then seemed to be the art that was most likely to realise this dream. ‘Cinema is true. A story is a lie’, said Jean Epstein. This truth could be understood in different ways. For Jean Epstein, it was writing in light, no longer inscribing onto film the image of things, but the vibrations of sensible matter which is reduced to the immateriality of energy; for Eisenstein, it was a language of ideograms directly translating thought into visible stimuli, plowing Soviet conscience like a tractor; for Vertov, it was the thread that was stretched between all the gestures that constructed the sensible reality of communism. Initially the ‘theory’ of cinema was its utopia, suitable for a new age in which the rational reorganisation of the sensible world would coincide with the movement itself of the energies of this world.

When Soviet-artists were asked to produce positive images of the new man and when German filmmakers came to project their lights and shadows onto the formatted stories of the Hollywood film industry, this promise was apparently overturned. The cinema that was supposed to be the new anti-representative art seemed to be just the reverse: it restored the linkage of actions and the expressive codes that the other arts had tried hard to overthrow. Montage, once the dream of a new language of the world, seemed to have reverted to the traditional functions of narrative art: the cutting-up of actions and the intensification of affects that ensure the identification of the spectators with stories of love and murder. This evolution has nourished different forms of skepticism: the disenchanted vision of a fallen art, or, conversely, the ironic revision of the dream of a new language. It has also nourished, in different ways, the dream of a cinema that would rediscover its true vocation: there is Bresson’s reaffirmation of a radical break between the spiritual montage and automatism that are characteristic of the filmmaker and the theatrical play of cinema. Conversely, there is Rossellini’s or André Bazin’s affirmation of a cinema that in the first place should be a window opened to the world: a means to decipher it or to make it reveal its truth in its appearances as such.

I thought it necessary to return to these periodisations and oppositions. If cinema has not fulfilled the promise of a new anti-representative art, this may not be because it has submitted itself to the laws of commerce. It is because the wish to identify it with a language of sensations was contradictory in itself. It was asked to accomplish the century-old dream of literature: to substitute the impersonal deployment of signs written on objects or the reproduction of the speed and intensity of the world for the stories and characters of the past. However, literature was able to convey this dream because its discourse of things and their sensible intensities remained inscribed in the double play of words that hide the wealth of the sensible from view and let it shimmer in the minds. It could only take over the dream of literature at the costs of making it into a pleonasm: piglets cannot be piglets and words at the same time. The art of the filmmaker can only be the deployment of the specific powers of his machine. It exists through a play of gaps and improprieties. This book is an attempt to analyse some of its aspects on the basis of a triple relation. First, there is the relation of cinema with the literature that provides it with its narrative models and from which it is trying to emancipate itself. There is also its relation with the two poles where it is often thought that art is lost: where it reduces its powers, putting itself at the service of entertainment only; and where on the contrary it strives to exceed them in order to transmit thoughts and teach political lessons.

The relation between cinema and literature is illustrated here with two examples taken from very different poetics: the classic narrative cinema of Hitchcock, which retains from the plot of the detective film the scheme of an ensemble of operations suited to create and then dissipate an illusion; the modernist cinema of Bresson, which relies on a literary text to construct a film demonstrating the specificity of a language of images. Both endeavors, however, experience the resistance of their object differently. In two scenes from Vertigo, the master of suspense’s ability to let the narrative of an intellectual machination coincide with the mise-en-scène of visual fascination seems to fail him. This failure is not accidental. It touches upon the relation between showing and telling. The virtuoso becomes clumsy when he hits upon that which constitutes the ‘heart’ of the work he has adapted. The detective novel is in fact a double object: as the supposed model of a narrative logic that dissipates appearances by leading from clues to the truth, it is also overlapped by its opposite: the logic of defection of causes and of the entropy of meaning, whose virus has been passed on from high literature to the ‘minor’ genres. Because literature is not only a depository of stories or a way to tell them, but also a way of constructing the world itself in which it is possible for stories to happen, events to follow each other and appearances to deploy themselves. This is proven in a different way when Bresson adapts a work of literature that is an heir of the great naturalist tradition. The relation between the language of images and the language of words in Mouchette is played out from inverted perspectives. The tendency towards fragmentation, meant to ward off the danger of ‘representation’, and the care taken by the filmmaker to rid his screen of the literary overload of images, have the paradoxical effect of subjecting the movement of images to forms of narrative linkage from which the art of words has freed itself. It is then the performance of speaking bodies that has to restore the lost thickness of the visible. But to that end, it must challenge the all too simple opposition made by the filmmaker between the ‘model’ of the cinematographer and the actor of ‘filmed theatre’. While Bresson symbolises the vices of theatre in a representation of Hamlet in a troubadour style, the strength of eloquence that he gives to his Mouchette secretly accords with that which the heirs of Brechtian theatre, Jean-Marie Straub and Danielle Huillet, give to the workers, farmers and shepherds taken from the dialogues of Pavese or Vittorini. The literary, the cinematographic and the theatrical then appear not as the characteristic of specific arts, but as aesthetic figures, relations between the power of words and that of the visible, between the linkages of stories and the movement of bodies, which transgress the borders assigned to the arts.

Which body can be used to transmit the power of a text – this is the same problem that Rossellini faces when he uses television to bring the thought of great philosophers to the public. The difficulty is not, as is prevailing opinion, that the flatness of the image runs counter to the depths of thought, but that each of their characteristic densities opposes itself to the establishment of a simple relation of cause and effect between them. Rossellini then must give the philosophers a rather special body so that a certain density can be felt within the forms of another density. It is the same passage between two regimes of sense that also plays a role when cinema, with Minnelli, attempts to put the relation between art and entertainment into a mise-en-scène – and into songs. We may think that the false problem of knowing where one ends and the other begins was resolved when the champions of artistic modernity had opposed the perfect art of acrobats to the outdated emotions of stories. But the master of musical comedy shows us that the labor of art – with or without a capital A – consists entirely of constructing transitions between one and the other. The tension between the play of forms and the emotions of stories on which the art of cinematographic shadows feeds tends towards the utopian limit of pure performance, without being able to disappear in it.

This utopian limit also led to the belief that cinema is capable of closing the gap between art, life and politics. The cinema of Dziga Vertov presents the perfect example of thinking about cinema as real communism, identified with the movement that is itself the link between all movements. This cinematographic communism, which challenges both the art of stories and the politics of strategists, could only put off specialists on both sides. What remains, however, is the radical gap that enables one to conceive the unresolved tension between cinema and politics. Once the age of belief in the new language of the new life had passed, the politics of cinema became entangled in contradictions that are characteristic of the expectations of art criticism. The way we look at the ambiguities of cinema is itself marked by the duplicity of what we expect from it: that it gives rise to a certain consciousness through the clarity of a revelation and to a certain energy through the presentation of a strangeness, that it simultaneously reveals all the ambiguity of the world and the way to deal with this ambiguity. Onto this we project the obscurity of the presupposed relation between the clarity of vision and the energies of action. If cinema can clarify the action, then it may do this by calling into question the evidence of that relation. Jean-Marie Straub and Danielle Huillet do this by leaving it to a couple of shepherds to argue about the aporias of justice. Pedro Costa in turn reinvents the reality of the journey and wanderings of a Cape Verdian mason between a past of exploited labor and the present of unemployment, between the colorful alleys of the slums and the white cubes of social housing. Béla Tarr slowly follows the accelerated walk towards death of a little girl which epitomises the deceptiveness of great expectations. In western Algeria, Tariq Teguia combines the meticulous trajectory of a surveyor and the long journey of migrants on their way to the promised lands of prosperity. Cinema does not present a world that others have to transform. It conjoins, in its own way, the muteness of facts and the linkage of actions, the reason of the visible and its simple identity with itself. Politics should use its own scenarios to construct the political effectiveness of art forms. The same cinema which, in the name of the rebels, says ‘Tomorrow belongs to us’ also marks that it has no other tomorrows to offer than its own. This is what Mizoguchi shows us in another film, Sansho Dayu, the story of the family of a provincial governor who is driven from his post because of his concern for the oppressed peasants. His wife is kidnapped and his children are sold as slaves to work in a mine. In order for his son Zushio to escape so that he can be reunited with his imprisoned mother and fulfill his promise to free the slaves, Zushio’s sister Anju slowly drowns herself in a lake. But this fulfillment of the logic of the action coincides with its bifurcation. On the one hand, cinema participates in the struggle for emancipation, on the other, it is dissipated in the rings on the surface of a lake. It is this double logic that Zushio takes into account when he resigns from his functions to join the blind mother on her island as soon as the slaves are freed. All the gaps of cinema are summed up in the movement with which the film, having just presented the mise-en-scène of the great struggle for liberty, says in one last panoramic shot: These are the limits of what I can do. The rest is up to you.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

translator’s notes

* The term ‘gaps’ in English summons notions of absence and inadequacy. Rancière’s choice of the term ‘écarts’ does not simply imply the inadequacies of cinema. The gaps of cinema are the results of cinema being other to itself – this internal heterogeneity producing extensions or relations with literature, politics, and other art forms. Gaps and extensions make cinema overflow itself. These ‘gaps’ are precisely what make it excessive in the sense of extending the questions and experiences it produces to other ‘non-cinematic’ fields. Commenting on this notion of gaps in Les écarts du cinéma, Rancière recently explained: ‘The problem of gaps…calls into question the idea of cinema as an art form that is thought to be a product of its own theory and specialised body of knowledge, by pointing out the plurality of practices and of forms of experience that are brought together under the name of cinema. From this starting point, I was prompted to bring together the texts I had written since Film Fables from the point of view of the gaps which, by drawing cinema outside of itself, reveal its inner heterogeneity’ (‘Questions for Jacques Rancière around his book Les Écarts du Cinéma: Interview conducted with Susan Nascimento Duarte’, Cinema: Journal of Philosophy and the Moving Image, 2 [2011], 196-7). Endnote written by Sudeep Dasgupta, with special thanks to Jacques Rancière.

* This is a slightly revised version of the text found on Necsus.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Below you’ll also find the transcript of an interview with Rancière around, as found in Cinema: Journal of Philosophy and the Moving Image.

Questions for Jacques Rancière around his book Ecarts du Cinéma

Interview conducted by Susana Nascimento Duarte (New University of Lisbon)

CINEMA (C): Just like La fable cinématographique… (published in English as Film Fables), your 2001 book that was also entirely dedicated to cinema, Les écarts du cinéma, recently published by La Fabrique, is a collection of texts, which together provide support for your singular approach to cinema, and whose prologue attempts to explain the logic of this approach after the fact. How did this book come about, and how did you decide on the structure?

Jacques Rancière (JR): The theme of gaps was at the centre of the text that forms the prologue to this book. This text was a post hoc reflection on Film Fables, and shifted the axis of reflection somewhat. Fables looked at cinema through the lens of a tension between two regimes of art: the aesthetic regime, including the novelty of a writing with movement and the dream of a language of images; and the representative regime, with the resurgence of the art of telling stories in cinema, and distinctions between genres, which had been renounced in the old noble art forms. The problem of gaps is more a reflection on my own approach to cinema and all that this implies about the idea of cinema as an object of knowledge and discourse. It calls into question the idea of cinema as an art form that is thought to be a product of its own theory and specialised body of knowledge, by pointing out the plurality of practices and of forms of experience that are brought together under the name of cinema. From this starting point, I was prompted to bring together the texts I had written since Film Fables from the point of view of the gaps which, by drawing cinema outside of itself, reveal its inner heterogeneity: gaps between cinema and literature, which question the idea of a language of cinema, transformation of film-makers’ politics, which are also tensions between cinema and the theatrical paradigm, paradoxical relationships between entertainment and art for art’s sake, and so on. At each turn, it needs to be shown how an art form is intersected by other art forms, how it is impossible to separate the transformations that set it apart from itself, how it cannot be neatly assigned to a specific area of knowledge.

C: It could be said that the logic underlying these essays is the idea of the gap. However, you come back to the concept of fable, as a way of bringing together but not eclipsing the varieties of gap which, you say, characterise cinema and on which you have focused your writings about it. The fable is synonymous with a tension between the story and the constraints imposed on it by causality, and of a set of images that function as a way of suspending the story. But this is not specific to cinema. In your view, to what extent does the idea of the fable seem decisive to the way cinema is thought about today and the contradictions you have identified as having existed from the outset?

JR: The fable is a core idea of the representative regime, and within this regime the fable defines the connection between the incidents that occur in the poem, and the art forms for which the latter acts as the norm. In this way, it is an essential way of measuring to what extent a new art form has adopted such a logic. From the start, cinema was caught between two opposing regimes: on the one hand, in the representative regime, the fable was what set cinema apart from simple popular entertainment, and on the other, it was what separated cinema from the forms of artistic novelty which renounced the fable and which saw in the art of moving images an art form that would be able to transform the will of art into perceptible forms, by dismissing story and character. The history of cinema is, to me, the history of this tension between two logics. This is not just a tension between the story and the image that arrest it. I attempt to bring out the divided nature of the fable in my analysis: there is a visual plot, which modifies the narrative plot, or there may even be a tension between two visual plots. This is the focus of my analysis of Robert Bresson’s Mouchette. Shots play two different roles in this film, and this leads to the development of two different visual plots. On the one hand, the shots tend to become emptier, and thus act as a pure sign in an arrangement of images – a glance and a gesture, or a gesture and its outcome. It is thus made to serve the narrative in a story of a hunt, in which the young girl is only prey. On the other hand, the shots become more dense, and serve as a frame for a deviant performance by Mouchette’s body: half of her is resistant to the messages and looks of others, and half is inventing deft gestures which form her own performance and which trace a narrative path that is distinct from the hunt, although these strands remain entangled throughout the film.

C: In the prologue to Film Fables, you directly related cinema to a pre-existing conceptual framework, the one concerning the “distribution of the sensible” and the regimes of art, while in your new book, although you return to the questions that you addressed in Film Fables, these are posed more explicitly from within cinematographic experience, which in your view is the experience of the cinephile and the amateur. You refer to a politics of the amateur, rather than that of the philosopher or the cinema critic. Could you explain the nature of your philosophical work on cinema, and how you see the relationship between philosophy and film?

JR: I talk about the politics of the amateur in this book, and this is consistent with the rest of my work: a way of practising philosophy that moves away from the dominant view that philosophy provides the foundation or truth of whatever practice we may be considering, be it politics, an art form or anything else. I have practised a philosophy that questions the division between disciplines and skills, and the division between practices and the metadiscourses that claim to be able to explain them. In my view there is therefore no single relationship between philosophy and cinema; rather, there is a variety of philosophical nexuses that can arise from various aspects of cinema. For example, in the article on Hitchcock and Vertov, the relationship of cinema to philosophy is implicit in the literature it adapts; in the article on Bresson, it is consistent with the idea of a language of images; in the article on Rossellini, it is the incarnation of thought in the philosopher’s body, and so on. None of these nexuses arises from a specific body of knowledge that might be called a theory or philosophy of cinema.

C: You write about the privileged experience that constitutes an encounter with a film. What is it that defines this encounter, which paradoxically manifests itself as a gap, in that it is impossible to identify cinema completely with art, or theory, or politics?

JR: This idea of the encounter should not be seen as religious. This is partly linked to the generation in which I grew up: the status of cinema as an art form, the criteria for judging films, and the hierarchy of directors were all rather uncertain. There was no settled canon. The relationship between artistic and political judgements was also somewhat fluid: the Brechtian paradigm that was dominant at the time was very useful for criticising images in the media, but provided little by way of a framework for judging films as such. Under such conditions, the effect produced by one or more films was often what provided the feeling of the specific nature of cinema, or established a connection between the emotions of cinema and political affects. This situation is linked to a methodological question. Precisely because cinema is not a language, it does not delimit an object of knowledge that arises from a systematic reasoning, learning cinema lends itself particularly to the application of methods of intellectual emancipation: as Jacotot said, “learn something, and relate everything else to it.” Cinema is “learned” by widening one’s scope of perceptions, affects and meanings, which are built around a set of films.

C: Your relationship with cinema is built around three gaps: between cinema and art, cinema and politics, and cinema and theory. For you, cinephilia is an illustration of the first type of gap, in that it throws confusion among the accepted judgements about cinema; and at the same time, it enables you to highlight the other two types of gap: if cinephilia calls into question the categories of modernism in art, and introduces a positive understanding of the impure nature of art, it is because it “struggles to comprehend the relationship between the reason underlying its emotions, and the reasons that enable one to adopt a political stance towards world conflicts.” One shifts from an intimate relationship between art and non-art (as determined by the difficulty of identifying criteria which can distinguish one from the other) to the impossibility of reconciling the appropriateness of a director’s gesture with the political and social upheavals in society. What is the relationship between these two types of gap? To what extent has theory shown itself incapable of filling these gaps, and (in your view) to what extent has it become, conversely, the place in which these gaps are rendered manifest?

JR: In one sense the cinephile gap is an extension of an old tradition whereby artists and critics contrast rigorously accurate performances of minor art forms with culturally accepted forms. These gaps, which are a matter of taste, are always difficult to rationalise. But, in this case, this gap in taste arose at the same time as the huge theoretical upheaval that is summarised by the word “structuralism” and which claimed to be able simultaneously to renew the paradigms of thought, science and art. Passion for cinema was therefore swept up in the large-scale rationalisations of the 1960s, when the desire was to bring everything together into a general theory. It was claimed that these theories corresponded to the political agitation of the time, to anti-imperialist and decolonisation movements, to the cultural revolution, and so on. There was a large gap between taste-based judgement, theory and political commitment, which was difficult to fill using the notion of mise-en-scène alone, which itself seeks to hide the heterogeneous nature of film, and to associate it artificially with a single artistic will. Conversely, awareness of this gap could encourage a practice that is very different from “theory”: the object of this practice is understood to be the product of an encounter between heterogeneous logics.

C: There is the encounter with a film, but you also mention the experience of returning to a film, watching a film or films again, either to make comparisons with one’s memories — for example, the “vivid impression” left by a particular shot, or the more general impression left by a work that beguiled us — or to question an interpretation that was provided previously. Could you explain your relationship with cinema when you revisit films in this way, given that re-viewings are transformations, deformations and prolongations by memory and speech of the material object that is film, and lay open the variations in your thoughts within the territory of cinema? In what way has the unstable reconstitution of the perceptions, affections and traces that have been left by the films you have encountered been influenced by changing theoretical, political and philosophical concerns over the course of your life? What is the relationship between films you have watched and re-watched, your thoughts about cinema, and your work in the political and aesthetic fields?

JR: Here we see the conjunction between a structural necessity and a contingent reason. The first is part of the aesthetic regime of art. The idea of art is defined less by a way of doing things than by whether or not one belongs to a universe of sensibility. The codes and norms of the representative regime are replaced by other ways of “proving” art, which consist of a weaving together of memories, stories, commentaries, reproductions, re-showings and reinterpretations. This woven fabric is perpetually shifting: in ancient theatre, Dutch painting, “classical” music, etc., there is a constant metamorphosis of the ways in which these art forms can be perceived. The same is true of cinema. There is a practical problem, however: cinema, which is said to be an art that is technically reproducible, was for a long time an art form whose works were not accessible to methods of reproduction. You never knew if you would see a film again, and it changed in your memory, and in the texts that discussed it; you were surprised when seeing it again to find that it was very different from how you remembered it, particularly since individual and collective perceptual frameworks had changed in the meantime. This is the idea behind my various visions of Europa ’51 (1952): the representation of the communist people, and of the marginal world on the edges of it; the acts of the well-meaning woman who attempts to navigate between the two; her experience of the brutal speed of the production line; the relationship between what she does and the communist explanation of the world or with psychiatric rationalisations — all of which is amenable not only to judgement but also to completely different interpretations, seen in the light of the time of the cultural revolution, the lessons of the Left, of Deleuze etc.

C: In the essay about Hitchcock and Vertov, these two directors represent two opposing ways of coming after literature. What does this mean in each case? This essay, as the title indicates, travels from Hitchcock to Vertov, i.e. from submitting cinematographic machinery to the mechanism of fiction and the Aristotelian logic, to a cinematographic utopia which denies the possibility of a storytelling art form, and back to Hitchcock via Godard, who, in his Histoire(s) du cinéma (1988-98) seeks, in a Vertovian gesture, to release the shots created by the master of suspense from the plots in which they are trapped. However, in your view, the analogy goes no further. What is the difference between the way in which Vertov dismisses story-telling and the way in which Godard dismantles stories?

JR: Vertov’s work is part of the system of historical modernism: eliminating stories and characters, which also means eliminating art itself as a separate practice. His films are supposed to be material performances that link together all other material performances, and these connections are meant to represent communism as a tangible reality. This aesthetic communism, in which all movements are equally possible, is a way of distancing the model of historical plotting on which the Soviet state found itself dependent: a model of strategic action supported by faith in a historical movement. As for Hitchcock, he used moving images to serve his stories, in other words he relegated machines to the status of instruments of narrative machination. Godard wants to release images in order to allow cinema to achieve its primary vocation and atone for its previous servitude to stories, in which is included the bad side of History in the form of 20th century dictatorships. The fragments that he thus isolates, though they link together as smoothly as those of Vertov, have little in common with the energies that Vertov wished to let loose. These images inhabit an imaginary museum in the style of Malraux, and they are testimonies and shadows that speak to us of the horrors of History.

C: In your analysis of Mouchette (1967), you try to show that Bresson’s search for cinematographic purity, detached from references to theatre and literature, from classical theatrical and literary conventions, had precursors in literature and theatre. What are the gaps that are examined here?

JR: Bresson is emblematic of the idea of pure cinema as a language of images. He makes fragmentation into a way of avoiding representation. The paradox is that this idea of a language of images ends up being a “linguistic” theory of montage, in which each shot is an element in a discourse-like statement. From this there results an over-emphasis on causal and organic relationships between elements. And yet this is exactly what is at the heart of the representative system. It is as though the Aristotelian model of the poem as an “arrangement of incidents” were applied to the combination of meaningful elements. Images lose their independence, their own duration and their ability to generate a variety of aleatoric image series. The body of the actor — the model, according to Bresson — is the element that must reintroduce this potentiality. This is accomplished using the gap between the actor’s behaviour and the traditional psychological expressive acting. However, the gap that Bresson distinguishes between “cinematography” and “filmed theatre” was in fact first identified by theatre reformers.

C: In your analysis of The Band Wagon (1953), in the essay “ars gratia artis: la poétique de Minnelli” [“ars gratia artis: the poetics of Minnelli”], to what extent is Minnelli’s cinematography both merged with and separate from that of the modern avant-garde director, with whom you compare him, and who dreams of the end of boundaries between art forms, and the equivalence between great art and popular entertainment?

JR: The Band Wagon is an adaptation of a Broadway show. Minnelli came from a show business family, for whom popular entertainment was an art. His work as a director was firmly within this tradition, and this is why he put so much emphasis in this film on the clash between the music hall artist and the avant-garde director. The director proclaims the great avant-garde credo: art is everywhere. What matters is the performance, not whether the subject is noble or lowly. This credo is, above all, a way in which art can give meaning to itself, by showing itself capable of absorbing anything, while remaining equal to itself. The result is a surfeit of the spectacular. Minnelli takes a different route. For one thing, he adheres to genre conventions: a musical comedy, which is primarily a series of musical and dance numbers, and melodrama, which is primarily defined by the emotions its subject can excite. Using this as a starting point, he deploys cinema’s ability to displace genre requirements, by incorporating romantic emotion into the musical performance, and choreography and visual fireworks into melodramatic episodes. Art involves metamorphosis, not displaying itself. His films are faithful to MGM’s motto: ars gratia artis, or art for art’s sake. This is true for “popular” films, even though the term is often reserved for works aimed at connoisseurs.

C: The essays on Straub and Pedro Costa clearly demonstrate that a film is not a political message and cannot be measured by its theme or by well-intentioned relationships with what is filmed. In your view, where does their cinematic politics reside, exactly?

JR: Politics in film is not a simple strategy by which awareness and activism are elicited, using well-defined means — as montage was, once upon a time. It is a complex assembly of several things: forms of sensibility, stances adopted towards the current world order, choices about the duration of a shot, where to place the camera, the ways in which the entities being filmed relate to the camera, and also choices about production, funding, equipment and so on. These assemblages give rise to various types of adjustment. Straub and Costa are on the side of the oppressed. They work outside the mainstream, use non-professional actors and make films that are distanced from dominant fictional paradigms. Beyond this point, their methods differ. Straub constructs films around literary texts, but he never “adapts” them. These texts work in two different ways. Initially, they provide, in a Brechtian way, an explanation of or judgement on the characters’ experiences. More and more, though, they specify a particular type of high register or nobility of speech, and the amateur actors, portrayed against a backdrop that illustrates the condensed power of nature, are there to test the ability of common people to utter such speech and rise to its level. This dual purpose is presented in an exemplary way in the extract from Dalla nube alla resistenza (1953) on which I comment, in which a shepherd and his son discuss, as they do in Pavese’s story, the reasons for injustice. Pedro Costa disposes of explanation, and of the heroic aspects of the backdrop and speech. He plunges with his lightweight camera into the life of immigrants and those on the edge of society, and into their relationship with time. He films these people first in shanty towns and then in new social housing. He is committed to showing that these people are able to create ways of speaking and attitudes that are equal to their own fate. He seeks to distil from their lives, environments and stories the nobility of which all people are capable. The film is in the style of a documentary about their lives, although all the episodes were invented as the film progressed, as a way of condensing their experience and making the film less personal. They use different methods, but in neither case do these film-makers seek to express their politics by denouncing a situation; rather, they demonstrate the capabilities of those who are living it.