Talk with John Akomfrah. November 21 2013, Gent. In the context of the DISSENT ! series. Moderated by Stoffel Debuysere.

This talk took place on the second day of John Akomfrah’s visit to Belgium, after a screening of his second feature film, Testament (1988). “If we loose the ruins, nothing will be left”: the quote by Zbigniew Herbert which opens the film sets the tone for this post-colonial mourning play, composed as a blend of lyrical drama and archival documentary. There are no heroes in this “war zone of memories”, only ghosts, drifting through history as if through an arbitrary world. One of them is Abena, a reporter returning to Ghana after being sent to exile following the 1966 military coup that overthrew the continent’s first independent government led by Kwame Nkrumah. Taking grief by the hand, she wanders through scarred landscapes in search for remnants and companions of her past, only to find there is nothing to return to, no epitaphs for those who were left behind, no records that document the pursuit of the first experiment of Pan-African Socialism, no ruins that can testify to the struggle to escape the grip of colonialism. The absolute dream of the diasporean, the return to a place called home, turns out to be an impossible dream.

“This film is personal in very concrete terms. All the events in it are the events that made the flight from Ghana possible. Had the coup not happened, I would probably have been somewhere in Moscow, East-Germany or some communist shit hole. Because my parents were both involved with the party, my mom was at the school teaching there, so everything that happened to my life is as a result of those events. At that time I was groping for something that has now become, in the 26 years since we did the film, almost like a genre. I’ve must have seen at least fifteen films dealing with west-African people who go back for death, in search for something or someone, in the process of discovering that the person is not there or the place is gone. But this was not a certainty when we made the film. Most of us, even in the early 1980’s, still believed that the diaspora was a kind of temporary zone. The making of this film emotionally convinced me that there is some legitimacy in thinking about diasporisation as a what Stuart Hall calls a “permanent disturbance”. There is really no other space before it to return to, because the process of the flight so transforms you, and by implication you can never go back to the place that you’ve left behind. When you go, what you’ll see will be skeletons but not much else. Which is usually the sign that you should move on. There’s only death here, you must go forward.

It is a very painful memory because my father is buried in that cemetery you see at the end of the film. At the time there were lots of lootings of gravestones and you know that there is something really wrong in a place where one starts robbing the dead, something seriously profoundly wrong. But there was a more serious robbery of the dead happening at that time and that’s why the film took the form that it did. In 1987 I was in Burkino Faso where I met some of the great African filmmakers, who all seemed to know that Werner Herzog was in Ghana making a film, and they would say “you should go to Ghana and make a counter-film – tell them about the real Ghana!” Part of the reason why I finally went was because that Herzog story provided a sort of impetus, but the real reason was to try to make a film on Nkrumah and the party. At the time however the theft of that memory was almost complete: it was illegal to talk about Nkrumah, one couldn’t even mention his name, it was illegal to make a film about the CPP, the party that he led. There was a guy from the ministry of information standing next to me during every scene, to make sure we didn’t talk about Nkrumah. So the allegorical form that the film took was partly an attempt to deal with the policing of it. You have to remember this is late 1980’s: everything, including the rhetorics of the coup, had been played out. The coup happened because the military and its supporters abroad – America, France, the usual sources – said that Nkruma was running the country down and that what was needed was this dose of realism from the military, who would bring prosperity etc. In 1987, twenty years after the military experiment, it was sometimes possible to buy fish which had worms in it, things had gotten that bad. All the rhetorics, including that of African-socialism, had been played out and we were coming in at the end of the utopian pronouncement, both of the original anti-colonial figures as the people who replaced them. So it really was a kind of war zone of memories.

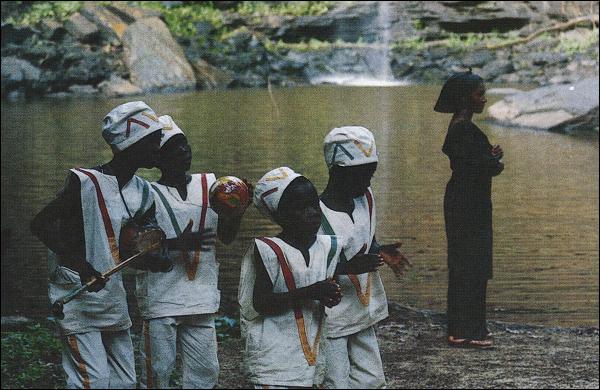

I literary went there to make more of a standard left-wing type of film. There was always this idea that there was this woman who would go back, but I thought it would be possible to talk more openly, so the film was going to be a kind of debate-driven, much more vibrant, Eric Rohmer-like talkie about Nkrumah and African Socialism. But it became clear very quickly that this was not a possibility, so I really found myself being forced to deal with the folkloric resources that the country had. When the film was shown in Cannes, a lot of European writers would say to me “oh, this is very avant-garde isn’t it, how would Africans take it?”, and I said “listen, this is one of the few films I’ve made, that when you show it to a ten year old in Ghana they’ll know exactly what the film is about!” Especially if they’re Ga from the coast side. Because, in that part of the world, we have a very regimented, in fact the most ordered approach to death, more than we do to life. Every color of mourning – black, white, red, blue – means something very specific. It means there’s a certain proximity of the person to death. You’re either, in case of red, angry, black, you’re resigned to, white, you’re definitely very depressed, and blue, you feel a mixture of anger and depression. So every color in the film is coded in the folk psyche. All across Ghana, every kid will know exactly what the colors mean. When you start to refer to allegory as a means by which you get to the source, this is a very standard West-african device. So people might not understand exactly what all those allegorical shifts mean, but they know you don’t mean that. They know you mean something else. The space of narration is empty. Because they know the actual story is elsewhere. It’s like when you mourn, its not about a specific thing, it’s not about details about a person’s life, you’re mourning the absence of that figure.

The image of the baby twins in the film is connected to this. There’s a kind of cult of twins across West-Africa. They are sort of omenic: they are both harbingers of something good, but also something not very good. I didn’t want to make something that is all symbolic, I wanted something which is not a metaphor but an actual metonymy. I was searching for material and I just came across these archive images of twins conjoined in the 1950s. And you watch the film and they do the operation and you think “ok they’ve got everything they need to both stay alive”. Bit there was one organ that they didn’t know about, that one didn’t have, so one died. And this sense of twinning is something I have been preoccupied with a lot, it’s something I just made a piece about called Transfigured night. It’s based on a piece by Schönberg, Verklärte Nacht, based on a poem which pretty much tells you everything about my obsession with twins. The poem is about two lovers who are walking through the woods on a moon lit night and the woman says to the man “my love, I am yours but I need to confess to you on this night that I’m carrying someone’s child and it’s not yours”. The man says “ok, my love, do not worry because tonight the moon will transfigure our love. From this moment, we will be one and this love will bring this child into the world”. Something about the nature of the postcolonial movement reminds me of that. The postcolonial state goes to the postcolonial subject and says “I love you, were gonna be together but I carry these weird postcolonial elements inside and I promise you they won’t get in the way”, and the citizen says to that “we love you too”. Of course this love doesn’t last. The dream of unity, of being twin, of being identical, having an interest that is absolutely the same, seems to me to mark that moment of independence. For that reason I have always been fascinated, other than for folkloric reasons, in twins and especially because these are siamese. They really are joined, but they can’t survive without that space of relative autonomy.

I think necrophilia is absolutely central to how the diasporic imaginary works, and by implication for its filmmakers. When you think about it, in everyday speech, part of the urgency that informs black militancy – “Ahm shoutin, you fucked my people, and now we need justice” – the invocation of the dead made in this speech is one that requires endlessly to look to the dead for sustenance, for legitimation. For me that is a kind of feeding off the dead. And it is there throughout, it is part of the diasporic imagination, because you are aware of this moment of rupture and break, and if you are a new world diasporic figure that moment of rupture is marked by the triangle. If you listen to the spirituals and the gospels, they are infused with this necrophiliac imaginary. But I think filmmakers become even more in tune with it – so much of what I’ve done is about the dead. Figures who are no more. So much of the authority of the films comes from this act of mourning. Which in visual terms is a kind of consumption of those figures.”

In the beginning of the 1980’s, it became clear that the legacies of the Bandung moment and its varied postures of nonaligned sovereignty had effectively come to an end, and the narratives of liberation and overcoming, as well as their underlying mythologies, could no longer hold the critical salience they once had. This shift also had an effect on the counter-models of cinema, particularly those categorised as ‘Third Cinema’, an ambiguous term which referred to the forms and practices that were cultivated in subaltern cultures in response to the hegemony of Western cinema, as dialectical weapons in the process of decolonisation. “Inscribed in the militant and nationalist pretensions of the term ‘third cinema’,” wrote Akomfrah in 1988, “is a certainty which simply cannot be spoken anymore. A certainty of place, location and subjectivity. What now characterizes the ‘truths’ of cinema, politics and theory is uncertainty. “ In times of uncertainty one can no longer hold on to stories of salvation and redemption, depending upon a utopian horizon or a prospect of homogeneous collectivity toward which the emancipatory history is imagined to be moving. In times of uncertainty, other fictions tend to be created, reports of wanderings without preconceived maps or destinations, forms of inquiry that are not in search for the one and only Truth, but for a sincerity of small truths; fictions that embrace the “unknowing” and oppose the view of history as a chain of events on a ‘road to salvation’ with that of a discontinuous drift through uncharted territories, in which action is ever open to unaccountable contingency, chance and peripeteia . In Testament the fiction takes on the tentative form of a “trauerspiel”, which Benjamin identified as fitting for a time “turned unheroic, requiring no redemption and no ultimate order”. In contrast to the dominant cultural form of tragedy, which relies on the illusion of totality or wholeness – of which the typical Hollywood spectacle is today’s prime manifestation – the allegorical trauerspiel brings life to experiences of absence and failure, the spaces in between that cannot be captured by the pursuit for an imposing knowledge of the absolute and the determined.

“A lot of the cinema I was schooled on was not only the European art tradition or even the Asian one – Mizuguchi, Ozu etc. For a cinephile the central supplement to the art cinema was the militant “third cinema” tradition, premised on the idea that the machinery, this indexical machinery of narrative filmmaking could participate in a project of social transformation of a utopian kind. I think there was a sense in which for three or four decades that was true. But if you’re making films in the 1980s this was a very tough call to make, a very difficult proposition, because the very language vernacular of the utopian was itself now in flux and in doubt in some way. So certainly the thing that a number of us started to try to do was redefine “third cinema”, to move it away from the militant posture. The need for an “imperfect cinema”, the need for a national address, the question of minorities, etc: all these things are important but they don’t need to be attached to some eschatological religious teleological narrative, which says if you have those things you will automatically go to nirvana. … it’s an impossible demand: if your films haven’t participated fully in this project of national renewal in the utopian kind, if you haven’t gone to the promised land, that by implication means you fail, because if the cinema only exists to verify those utopian horizons and we don’t have it, theres no raison d’être for your being. So the intent to break this limb was in part, not for the political project, but for the cinema itself. To save it from itself. Sometimes the filmmakers from themselves. So for Glauber Rocha you don’t have to do too much, but for someone like Solanas you really have to work hard, because The hour of the furnances is an extraordinary formal project by any definition. The fact that he didn’t need to socialise Argentina is neither here or there as far as I’m concerned. The effort in itself was fine. The desire to find a language to speak is worth applauding, I think, even if you don’t get utopia at the end. So that was what the project was about. We took a lot of criticism… just this real need to give legitimacy to a moving image culture spread across various continents, which had been growing for 40 years … if that’s the only way of calling itself real, the wall is gone. You should bury it all. You could see the wall coming down. You could see this was where we were heading, trying to disentangle the two, to disengage them. That was a worthwhile project.

There are two films, the openings to which I absolutely love: Far from Vietnam and the Hour of the Furnaces. The first five minutes of both films are extraordinary. Syncopated, energetic, “this is going somewhere, this is gonna happen”. “We can see the bombs, are we gonna stop them?” As exercises in cinema they were fantastic. The Hour of Furnaces: I would happily give up next hour and a half because I think the essential work is done literally in those minutes. Nobody had done it before, not even the great Cubans. Fantastic images, but they don’t need to be attached to projects of aspirational fantastic utopian possibilities. For example, what utopian projects are you guys gonna make a film about: overthrowing the Belgian state? … It used to be like that: we watched The hour of the furnaces and we thought we should be in Angola fighting. We wrote, four our us, to ask if we could join. The fact that you would have been dead in two minutes didn’t enter our mind… If the cinema’s model for agency was that you imitated and mimicked what was going on in the film then we’re gonna loose. A lot of the films that were inherited from the radical tradition were made it that spirit, but they don’t have to be consumed in that spirit to be of value. So the question really was about this notion of use value. How one could re-calculate use value in their light, in what appears to be a failure, both in terms of the ambitions of the film as well as the content. And that was really what we were grappling with in the eighties.”

Watch Testament here.

DISSENT ! is an initiative of Argos, Auguste Orts and Courtisane, in the framework of the research project “Figures of Dissent” (KASK/Hogent), with support of VG & VGC. The visit of John Akomfrah has been made possible with the support of Cinematek, le P’tit Ciné, Brussels Arts Platform and VUB Doctoral School of Human Sciences.