One of the central filmmakers in the 2010 edition of the Courtisane Festival will be David Gatten. Since the mid 1990’s, Gatten’s serenely beautiful handmade films have employed experimental techniques—cellophane tape ink transfers to optical printing—to explore the relationships between text and image, while at the same time investigating the shifting vocabularies of experience and representation within intimate spaces and historical documents. We’ll be showing one of his recent works (‘Journal and Remarks’, 2009) in the competition program, as well as his first film (‘Hardwood Process’, 1996) as part of the thematic program ‘Vital Signs’. What’s more, there will be a special screening of the first four chapters in the ongoing series ‘Secret History of the Dividing Line: A True Account in Nine Parts’ (started in 1996), based on numerous books, journals, and letters Gatten has discovered in the library of the William Byrd II family of 18th century Virginia.

David Gatten reflected on this project in an interview with Scott MacDonald, which was recently published in his book ‘Adventures of Perception: Cinema as Exploration‘. What follows is an edited version of that interview (you can find the PDF here).

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

David Gatten has been a fixture on the contemporary avant-garde media scene since the late 1990s. He has been active within the community of no-budget filmmakers and the network of micro-cinemas that has developed in recent years (for a time his home doubled as a micro-cinema); and like so many of his contemporaries, he has been fascinated with the possibilities of working directly with film—doing his own developing, inventing unusual procedures for generating images: for What the Water Said (1997) Gatten threw raw film stock into the South Carolina surf and allowed natural forces to etch imagery onto the filmstrip. Most importantly, Gatten’s remarkable ongoing project, Secret History of the Dividing Line, A True Account in Nine Parts, has become a pivotal work that implicitly reflects on a century of avant-garde film production, offering a new sense of that history. In the program notes he composed for The Great Art of Knowing (2004), Part II of the Secret History project, Gatten included this statement: “An antinomian cinema seems possible. A gentle iconoclasm?” These lines are revealing of Gatten’s sense of the Secret History project and of his identity as an avant-garde filmmaker. “Antinomian” has two relatively distinct meanings: on one hand, the word refers to those Christians who believe that faith alone is necessary for salvation; and on the other, it refers to forms of contradiction or opposition between principles that seem equally reasonable and necessary. Both senses of “antinomian” are relevant to Gatten and to the Secret History of the Dividing Line project.

Gatten’s reference to religious tradition is his way of situating himself in relation to that community of canonical avant-garde filmmakers for whom filmmaking has been a spiritual practice: Stan Brakhage, Bruce Baillie, Kenneth Anger, Jonas Mekas, Larry Gottheim, Nathaniel Dorsky… In both his Reminiscences of a Journey to Lithuania (1972) and Lost Lost Lost (1962) Mekas imagines a community of media-makers devoted to the primacy of the human spirit and to filmmaking as a way of participating in the ages-old quest for spiritual connection; and both within his films and within his life as a working artist, Gatten sees himself as a part of such a community. All four completed sections of Secret History of the Dividing Line, A True Account in Nine Parts—the title film, Secret History of the Dividing Line (2002); The Great Art of Knowing; Moxon’s Mechanick Exercises, or the Doctrine of Handy-works Applied to the Art of Printing (1999); and The Enjoyment of Reading, Lost and Found (2001)—are silent, serenelypaced, spiritually-evocative experiences; and the earliest of these films to be completed, Moxon’s Mechanick Exercises…, focuses specifically on the Gutenberg Bible.

The other, non-spiritual sense of “antinomian” is equally important for understanding Gatten’s films. The Secret History of the Dividing Line project accommodates filmmaking approaches that have often been understood as oppositional. During the late 1960s and early 1970s the film artists identified with what P. Adams Sitney called “structural film” seemed to abjure the forms of personal expression evident in the psychodramas of the 1940s and 1950s and in the expressionist cinema of Stan Brakhage after the late 1950s (and of filmmakers influenced by Brakhage: Carolee Schneemann and Nathaniel Dorsky, for example). Michael Snow, Hollis Frampton, Ernie Gehr, Paul Sharits, and others seemed to critique personal cinema, to question the very idea of the personal and to be bent on replacing “the personal clutter/the persistence of feelings/the hand-touch sensibility/the diaristic indulgence/the painterly mess/the dense gestalt/the primitive techniques” (Schneemann’s description of a structuralist filmmaker’s objections to her work, from Kitch’s Last Meal (1978), reprinted in More Than Meat Joy [New Paltz: Documentext, 1979]: 238) with rigorous, formal, highly intellectual approaches to shooting and editing, approaches that allowed for in-depth theoretical considerations of the nature of cinema itself.

The films in Gatten’s Secret History of the Dividing Line, A True Account in Nine Parts incorporate both approaches within an aesthetic that is rigorous, but not rigid, subtly expressive, but not self-involved. For example, Secret History of the Dividing Line is rigorously structured and it incorporates a “hand-touch sensibility.” Like each of the subsequent films in the project, the title film is divided into a brief introduction and three sections, each of which is organized mathematically (Gatten describes some of the details in our interview). The first section begins with what appears to be a scratch down the center of the filmstrip (it was actually made by painstakingly tearing the filmstrip in two, then reassembling it), which leads into a series of visual texts: a timeline of dates of important historical and cultural events leading up to and away from the life of William Byrd II of colonial Virginia, who founded the city of Richmond; led the surveying party that drew the boundary (the “dividing line”) between Virginia and North Carolina; wrote one of the first detailed descriptions of American nature, History of the Dividing Line (written soon after the surveying expedition, but not published until 1841); and assembled one of the largest libraries in colonial North America. After the sequence of dates, the “scratch” divides the frame in two, revealing on one side, passages from Byrd’s official History of the drawing of the Virginia/North Carolina boundary, and on the other, comparable passages from his secret history of the same events, written before the official history and circulated privately to other colonial gentlemen. Gatten’s work with visual text, along with his precise, mathematical organization, recalls Frampton’s Zorns Lemma, while the “scratch” evokes the many filmmakers who have worked expressively directly on the filmstrip (Douglas Crockwell, Len Lye, Harry Smith, Brakhage, Schneemann, Lawrence Brose, Carl E. Brown, Jennifer Todd Reeves…).

Throughout the Secret History of the Dividing Line films, Gatten confirms and expands his synthesis of the intellectual and the emotional, of representation and abstraction, of image and text, of the public and the personal, and of colonial history and modern art practice. Each of the Secret History of the Dividing Line… films focuses on a variety of cultural artifacts that Gatten’s research has led him to, many of them books that were part of William Byrd’s library; and each evokes the accomplishments of many avant-garde filmmakers as well as of other moving-image artists. The Secret History project is not a critique of earlier cinematic accomplishments, the way “structural film” was a critique of “personal cinema,” the way feminist filmmaking of the 1980s was a critique of what had been a male-dominated field, and the way much of the hand-made, hand-processed avant-garde cinema of recent years is a critique of both the commercialism of industrial cinema and the pretensions of earlier generations of avantgarde filmmakers. Rather, Gatten’s project is a gentle iconoclasm, less a critique than a celebratory synthesis of the history and diversity of independent cinema, and, more generally, a meditation on the long, sometimes glorious, often troubled history of experimental cultural production and accumulation.

The following conversation with Gatten was recorded in August of 2006 and has been refined on-line.

MacDonald: I’ve always assumed a connection between your major multi-partite project, Secret History of the Dividing Line and Frampton’s seven-part Hapax Legomena, or perhaps with his Magellan project. I’m thinking about the idea of a multipartite work that reaches out not just to film history but to social history, art history, poetic history—all these other realms. And I’m wondering whether you conceived Secret History as a multipartite project.

Gatten: In 1994 I found my way to Frampton’s Circles of Confusion [Circles of Confusion: Film/Photography/Video, Texts 1968-1980 (Rochester: Visual Studies Workshop, 1983)], which was huge for me. Frampton’s approach to history and art, the mode of inquiry, especially in his writing, became an operating principle for me. In particular, “Incisions in History/Segments of Eternity,” where he tells the story about Craig Breedlove, became my touchstone. Breedlove built a car to break the world land speed record, a car that crashed, though Breedlove wasn’t seriously injured. The crash took exactly 8.7 [check] seconds to occur, and when Breedlove was interviewed immediately afterward about what he thought and did during those nine seconds, he talked for an hour-and-a half! Frampton does this wonderful conceptual riff with recorded time versus lived experience. And I was completely captivated by this—and then did research on Craig Breedlove. I actually got hold of the film footage of the crash (there was a camera in the car). My plan was to try and get the entire interview and slow down the nine seconds of footage so that it lasted ninety minutes. I didn’t do that project; instead I made a three-projector piece using that footage—my first use of 16mm. But, more important, that Frampton essay sent me to the library and I’ve been there ever since.

When I started what evolved into the Secret History of the Dividing Line project, I didn’t actually know I was making a film, much less a cycle of films. I didn’t know what I was doing. The same week I was at the beach doing the first section of What the Water Said [1997], I was reading a Susan Howe book, Frame Structures [Susan Howe, Frame Structures: Early Poems 1974-1979 (New York: New Directions, 1996)]. I had been introduced to Howe by one of my friends at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where I got my MFA, who knew of my interest in Circles of Confusion. In Frame Structures, which contained reprints of some of Howe’s early work, the final section is called Secret History of the Dividing Line. I found it fascinating. Howe draws mostly from a book her father wrote on Oliver Wendell Holmes; I think it’s called Touched by Fire.

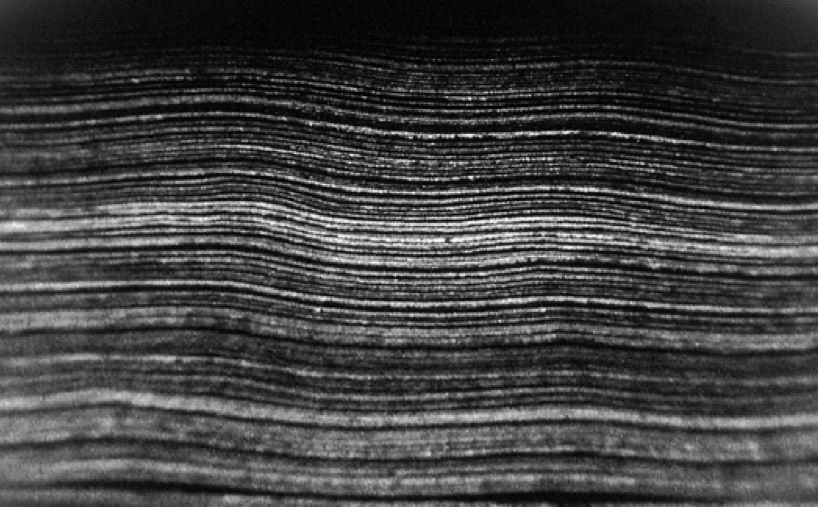

Also at that time, I was working with black leader in a way that had been inspired by Agnes Martin’s grid paintings. I had gone to a show of her work in Chicago, thinking, “Oh, she’s a minimalist painter, grid, Sol LeWitt…,” but I had an amazing experience in actually seeing the paintings, as opposed to slides or reproductions in a book. From twenty feet away, one of her grids may appear very regular, but from five feet away, you can tell that they’re not really regular, and from twelve inches away, you can see that the grids on these large eight-foot by eight-foot canvases are constructed with a twelve-inch ruler: she’s drawing a line and moving the ruler, drawing a line and moving the ruler; and so there are slight discrepancies, “imperfections,” in the grid, which, close-up, you can see is incredibly irregular and that Martin is in fact not simply a minimalist, but an abstract expressionist of a certain sort. That was exciting to me.

At the time I went to that show, this simple repetitive process seemed like such a healthy thing to do, and I wondered, “What might that repetitive process be in film?” Well, I was very interested in splicing, and was already working with cement splices, and I realized that splices are comparable to Martin’s lines. Now, if you make a perfect splice between black leader and black leader, you won’t see that splice; there will be no splice line at all; but since my splicer was slightly out of alignment, my splices weren’t invisible; this strip of leader was filled with these very small white lines. If you held the edited strip of leader eighteen inches from you, they looked like very uniform lines, but when I put the filmstrip on an optical printer and started looking at the individual splices, each one was incredibly different. I started filming the individual splices on the optical printer. I really zoomed in on them, and I’d let them last on screen for seven seconds, ten seconds. Each image was a unique object, as opposed to a uniform machine-made thing. I made hundreds of these images.

MacDonald: Is this what we’re seeing in the third section of the title film, Secret History of the Dividing Line?

Gatten: Yes. The white area on screen is where the blade irregularly scraped off all of the emulsion or into the celluloid base itself. Also, the cement forms bubbles, which you can see. At the beginning, I thought this was just a completely formal process, just a way of really looking at splices. Six months or so later, I saw that Howe book and thought, “Wow, ‘secret history of the dividing line’; the splice is a dividing line that’s supposed to be invisible; it’s what’s been repressed…I’m going to steal that title! But maybe I should figure out what her title refers to.” In the acknowledgements in Frame Structures Howe reveals that the source for her title is two texts by William Byrd II of colonial Virginia: History of the Dividing Line… and The Secret History of the Line. I decided to read these books. The governor of Virginia had asked Byrd to write up an official account of the expedition, and that’s where the History of the Dividing Line, Run in the Year 1728 comes from.

The “secret history” was a genre at the time. Byrd had other secret histories in his library. Secret histories were almost always parodies or satirical sketches that circulated privately, among friends. In The Secret History of the Line, Byrd names himself “Steddy”; he envisions himself as the steady one, the sensible one, and he is very biting in his commentary on the party from North Carolina. There was great rivalry between Virginia and North Carolina, and Byrd thought the North Carolinians were a bunch of buffoons.

When I read the official history and then the secret history of the drawing of the boundary between North Carolina and Virginia, I realized that I recognized some of the areas that Byrd describes. As a kid at summer camp, I did a lot of inner-tubing and rafting on the Dan River; the western part of the line in the Byrd expedition crosses the Dan River several times. Bryd’s descriptions of the landscape and the river were so clear that I often knew (or imagined I knew) exactly where he was—I have very vivid memories of that river. It was a powerful experience to read that text and realize that it looks almost the same now as it looked three hundred years ago!

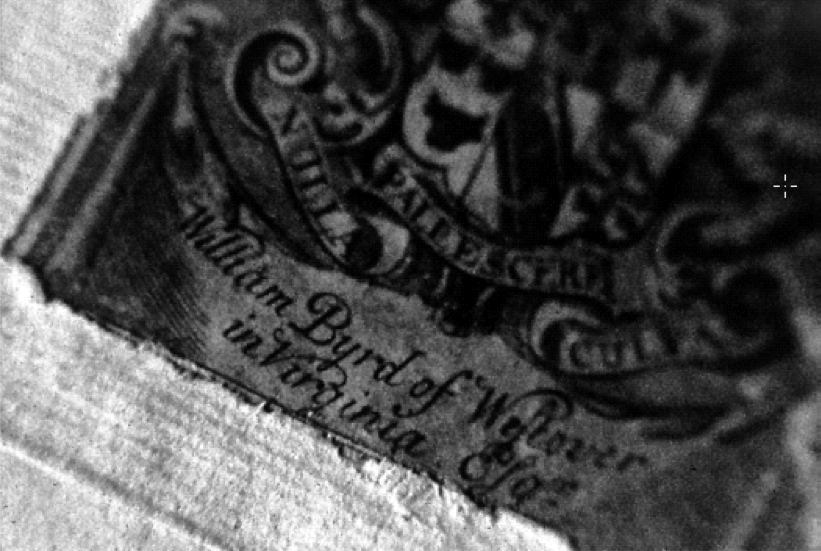

I continued to read as much about Byrd as I could and eventually got to the story of his library. In his time Byrd was most widely known for his library—his four thousand volumes were one of the two largest colonial libraries (only Cotton Mather’s may have been larger)—and the fact that he let people borrow his books.. Byrd had inherited books from his father, but every time he went back to England he would return with many more. Thomas Jefferson ended up with a number of Byrd’s books, and Jefferson’s library became the Library of Congress, so Byrd’s library in some way serves not only as the site for the transfer of European intellectual and philosophical and religious thought to North America, but as the foundation of our national library.

The fact of Byrd’s library was interesting to me, but what really hooked me was a 1958 article from the American Antiquarian Society journal by Edwin Wolf, who details his ten-year search to try and find Byrd’s books. William Byrd II died in 1744; his son, William Byrd III, squandered the family fortune and committed suicide on January 1st, 1777; and in order to pay the debts off, his widow had to auction off the library. A catalogue was assembled. It didn’t just list the books, but preserved the location of the books on the shelves, so we can see not only what Byrd collected, but how he thought about bodies of knowledge. There was no Dewey Decimal System at the time; Byrd’s way of putting things together tells us something about his thinking. I thought that was very exciting.

By this time, all these forms of division, and all these collections and connections, were coming together. There was the division of landscape through exploration, and the various reasons for dividing the two states: the official reason—the efficient collection of taxes by the British government—and the secret reason: the politics of colonies wanting access to intra-coastal waterways in order to get around the British trade tariffs for the shipping of tobacco. The drawing of the line between North Carolina and Virginia creates a new relationship that then binds the separated parts together in a new way. There were also the library and the auction as sites of collection and division. That library is still together on paper, even though it’s been physically divided: the books are dispersed all over the world. And I was thinking about the cinematic dividing line (and conjunction): the splice, which defines duration and creates our temporal experience of film. So at that point, I thought, “Okay, I want to do something with all this.” I didn’t want to just make a formal or a structural film, but to work with the documents and with history and bring in all of these other things I was excited about into a single work. I didn’t know exactly what to do, but Frampton’s writing was serving as something of a guide.

MacDonald: The splices that you optically printed were the germ of the Secret History of the Dividing Line project and the central section of your Secret History of the Dividing Line, but the film in which those splices appear wasn’t the first of these films you finished.

Gatten: No. My working in the library first resulted in Moxon’s Mechanick Exercises, or, the Doctrine of Handyworks Applied to the Art of Printing [1999]. One of the books from Byrd’s library, by Joseph Moxon, was the first manual of style for printers. I wanted to let this interesting text rub up against something else, specifically the Gutenberg Bible. The Gutenberg Bible represents that moment where the word and The Word become culturally fixed in a new way; it’s a point of transition from scribal reproduction to mechanical reproduction. I decided to use the Joseph Moxon text as a source for instructions on how to recompose the Gutenberg Bible material that I’d collected by using cellophane tape to “translate” text from the pages of different translations of the Bible onto a strip of plastic that can move through a projector. My process involves putting scotch tape down over a text or an image in a book and boiling the paper away so that the glue from the tape soaks up the ink and can then be contact printed onto highcontrast stock, which creates a negative; then I edit that negative in A, B, C, D rolls and sometimes optically print some of the material to slow it down and change the rhythm. Working that way is very much like a kid using silly putty to lift images from the comics and then being able to stretch characters’ faces. For Moxon’s Mechanick Exercises, I let Moxon direct: I made an interpretation of Moxon’s instructions for a typesetter and applied them to the material I had collected. I thought, “Okay, Moxon says this; that means I should do this with these captured texts,” and the result would affect the visual layering or the pacing, or the size of the translated texts in the film.

Translation, in the most conventional sense and in other senses too, had become a central interest. I looked at and worked with five different translations of the Bible, thinking about those translations alongside the two different Byrd histories, the secret history and the official history: that is, the “translation” of Byrd’s experiences into one form, then another. I was also interested in the general politics of translation: the issue of access to the Bible, and how the control of the information in the Bible evolved.

MacDonald: To what extent does your going back to that Gutenberg moment relate to the current transformation from mechanical technologies to all the new digital technologies?

Gatten: I see it as a direct relationship. I was trying to address that very issue. After the Gutenberg printing press, and the Gutenberg Bible, the text was fixed, but meaning was unfixed. The dissemination of texts gave way to the proliferation of interpretations. Books were still very expensive, but far less so than when they were reproduced by hand, so more people had the opportunity to interpret the Bible and other writings as well. In the late 1990s, similar things were happening; everyone was very excited about digital technology and the ways in which it was unfixing traditional text and texts. This was the moment after analog video, when digital video was starting up, and it seemed as if DV was going to answer everyone’s questions about access to the means of reproduction. I thought, “Well, maybe if I can go back to this earlier transition in print culture, I’ll be able to learn some things.” At that point there weren’t specific answers that I was hoping to pull out of the older material; it was just my way of thinking through these huge cultural changes.

I finished Moxon’s Mechanick Exercises in 1999. By that point I was committed to a larger Byrd project because I’d read about his daughter, Evelyn, and her love affair with Charles Mordant. That story gave the Byrd saga an entirely new dimension. Some of what has come down to us about Evelyn is the stuff of legend. But it does seem clear that she went to England in 1723 and met this man who was the grandson of the Third Earl of Peterborough, Byrd’s main political rival in England at the time. The Peterboroughs were Catholic; the Byrds were Protestant. Evelyn’s father found out about the budding romance, and Evelyn was shipped back to Virginia, where she refused to see suitors. It turns out that she carried on a secret nine-year transatlantic correspondence with Mordant, who eventually travels to the colonies under an assumed name and infiltrates Virginia society. Evelyn and Charles make secret plans to elope, but they’re betrayed by Byrd’s secretary. The ship sails with Mordant tied up on the ship; Evelyn is prevented from going aboard. And during that voyage the ship goes down; everyone aboard is lost. Evelyn is heartbroken; she confesses to her friend that she feels that she can’t go on, and two weeks later she dies, at age 29, of heart failure. And the following spring, in 1738, the first of seventeen recorded sightings of her ghost is reported.

I thought, “Wow.” Here was an epic story, and a tragic love story, again about division—they’re apart for nine years (their only communication is through letters that are carried back and forth by hand); they’re divided by the ocean and by religion, but connected by text. It was becoming obvious that I couldn’t fit all of what I was learning about the Byrds into the little splice line film I was working on. By this time I’d also decided that the splice line film was going to be about the landscapes of Virginia and North Carolina—because to me the individual splices had begun to look like landscapes. I was realizing that I might need to make a love story film and ghost story film. But then even that wasn’t enough. I started to think about other aspects of the Byrd history that needed to be addressed if I were going to create some real sense of its many dimensions. I continued and continue to find the Byrd library fascinating. In 1997 a scholarly edition of the 1778 catalogue, meticulously annotated and researched by Kevin Hayes, appeared. It’s fascinating reading; I open it up all the time, just to read the titles and descriptions of Byrd’s books.

In the summer of 2001 I took a trip to try and find the fifty-seven locations that Byrd lists in the appendix of his History, and sure enough, many of them were still there with the same names. The border has shifted—Virginia has steadily gotten smaller; there were later border-drawing expeditions that enlarged North Carolina—so most of the 1728 dividing line is now in North Carolina, but I could find these places, and Ariana Hamidi and I spent three weeks camping along the dividing line and shot a lot of film. There will be two expedition films: the title film of the cycle, and another (it’ll be the eighth in the cycle) that will revisit the expedition with imagery of those points that are the abstractly envisioned by the splices in Secret History of the Dividing Line.

MacDonald: One of the central dialectics in that film is straight lines of either logic or geography versus the curvilinear reality of life. As we read the list of places where the surveying group stops, we cross many winding rivers, including the Dan. It’s also interesting how the names on the list reflect a particular historical moment in the process of the settling of Virginia. Right after the location “Indian Trading Path,” we move into a long section of Indian names. There are clearly English names imposed on the landscape at the beginning, then there are Indian names, and then at the end we go back to a preponderance of English names.

Gatten: The surveyors went about 240 miles from Currituck Inlet across North Carolina, about two-thirds of the way across the state as it now exists. In the European-settled areas on the coast the Native American names had been replaced by European names, then there was an unpopulated area or certainly a much less densely populated area in and around the Dismal Swamp where the group had Native American guides, so the names they were being told were the ones used by Native Americans. Then when they got further inland, into the piedmont area, the party just started naming things themselves. Certain places are named for members of the expedition; the Mayo River, for instance, is named after William Mayo.

What you said about the straight line versus the curved line was important to me throughout the film, which begins with the jagged line within the more uniform borders of the film frame and the “lines” of texts. I do love the idea that the surveyors are trying to go straight across something that is not straight and that that is then inscribed in Appendix list—another kind of line.

MacDonald: Conceptually, Secret Life of the Dividing Line reminds me of Frampton’s Gloria! I assume that’s a film you know.

Gatten: Gloria! is actually my very favorite film. But I have never thought about it in direct relation to Secret History of the Dividing Line.

MacDonald: What Gloria! does with beginnings and endings—literal, historical, material—you do with the idea of the line. Within the structure of the larger Secret Life project, at least as you envision it now, The Enjoyment of Reading (Lost and Found) is the fourth film, but it was the second one you finished. When we showed it at Hamilton College, it struck me that the opening texts were particularly hard to read. Did you mean for those texts to be right at the edge of readability?

Gatten: I’m always wanting things to be at different degrees of legibility, to pose different challenges for the viewer/reader, and I did want to start the film with something that was quite thin. Part of the difficulty in this instance is a function of the font that I chose: it made certain parts of the letters very thin, and in some prints of the film and in certain projection situations, maybe too thin. I think if I had it to do over, I would make those texts somewhat more legible. Because I make these films on rewinds I never know exactly what I’m going to end up with until the film is finished.

MacDonald: In the long first section, it looks as if we’re looking at microfilm. Were you actually filming off a microfilm reader or…

Gatten: No, again I’m using my cellophane-tape transfer process: lifting text from a book and “translating” it to celluloid. I had gone through the original catalogue of Byrd’s library and had copied down a couple hundred titles. I made transparency slides of eighty-one (I often make slides of images, and put them on a lightbox as a way of thinking about how to arrange them), but then decided to film the slides themselves. I took the gate off the optical printer, and put each slide where normally you would have the neutral density filter and then filmed the slide, racking in and out of focus. So, no, they’re not actually from microfilm, but I did intend to reproduce something of my experience of sorting through both microfilms and card catalogues in archives and to evoke the sense you have when you do that kind of research of there being so much material, some of which you glance at, some of which it you read carefully, much of which you can’t absorb, and some of which you first go past, then find yourself drawn back to. The series of descriptions of books in this section of The Enjoyment of Reading works in a similar way to the timeline at the beginning of Secret History of the Dividing Line in that there are certain moments of focus within a wash of information.

MacDonald: In the second section we get the color passage, identified as “emblems of love, that she [Evelyn Byrd] made while waiting, always waiting.” There are two parts to this passage; a blueish first section that is quite abstract, then a somewhat less abstract section of lovely out-of-focus imagery of light through leaves blowing in the wind. In both sections, your focus creates dots or circles of light. What exactly are we looking at there?

Gatten: In both sections you’re seeing a blue, foil-wrapped candle. At the beginning you’re seeing, in extreme close-up, the tip of the candle, and there is one flash when the wick actually comes into focus. The tip of the candle was filmed with extension tubes, which magnify imagery; basically you’re seeing the sun glinting off the blue foil and creating “circles of confusion.” I was moving the camera very slightly, just shaking it basically. For a moment, a bit of cobweb is visible between the wick and the edge of the candle, and then I pull back and you see that the candle is in the window, within more “circles of confusion.” I think of that image as one of the iconic images of a lover waiting: you put the candle in the window to signal to your beloved.

MacDonald: Your alluding to Frampton’s Circles of Confusion just now is interesting, given that this particular section is very Brakhage-ian. It strikes me that one of the things that you’re attempting to do in the larger Secret Life project is to bring together various supposedly oppositional avant-garde practices. At one point, Brakhage and Frampton were thought to be at opposite ends of at least one independent filmmaking axis: Brakhage was personal and romantic, Frampton detached and intellectual. Did you have both Frampton and Brakhage in mind as you were making this passage?

Gatten: Well, when I was looking through the camera and realized that what was coming and going were “circles of confusion,” of course, I thought of Frampton. But further, I had begun The Enjoyment of Reading (I already had the title for the film) with text after text, with a lot of reading from texts that I conjectured were of particular interest to William Byrd. For the second section I wanted to shift the focus of the film into Evelyn’s space, into color and into what I considered to be a different kind of “reading”: a reading of “the text of light.” I was thinking very specifically about Brakhage’s The Text of Light [1974] and also about the way the kinds of images in the Brakhage film and in this section of this film might be conditioned by the seven or eight minutes of literary text that have come before them; what kind of new space would open up visually, physiologically, conceptually, when we went from black and white letters to a color image—that was very much on my mind.

MacDonald: In the third section of The Enjoyment of Reading, little shards of text at the bottom of the frame allude in one way or another to the various stories in the project, and then we see several images of a decaying book; I can’t read the title.

Gatten: That was Religion of Nature Delineated [1738] by William Wollaston, the first of Byrd’s books that I was able to film, at the Virginia Historical Society in Richmond, something I was very excited about. This was in 2001, right when I was starting to understand that this was a project about the Byrds. I had made Moxon’s Mechanick Exercises and had been doing a lot of research in Chicago, but this was the first time I went down to Virginia.

Religion of Nature Delineated was a very fragile book, so fragile that they only let it out of the archive once every five years, so we (Ariana had agreed to assist me) felt lucky to have this opportunity. The staff there, all of whom were very nice and supportive of the project, brought the book out and we filmed it, after which they took it back into the archive, and we thought, “Wow, that’s gone for five years!” When we got back to the camera, we realized that we’d not removed the 85B orange color-correction filter for tungsten film. We’d been shooting in black-and-white Tri-X, and that meant the exposure had been off by almost a stop and a half. We went back to the counter and said, “Um, can we have that book back one more time?” And they were so sweet, they brought it back out, and we filmed it again—but now nobody will see that book for ten years. We were embarrassed about that.

MacDonald: You include a sonnet from Michael Drayton and give us time to read it; did you choose it because it’s something Evelyn read?

Gatten: I chose that particular sonnet because it fits the theme of the entire project. All of the films are explorations of different kinds of division and I’m especially interested in the kinds of division that create relationships that make it hard to take things apart. Drawing the dividing line through the land separated North Carolina from Virginia, but also created a social, economic, political relationship between the two colonies. For me, that line resonates with the idea of Evelyn Byrd and Charles Mordant being separated by an ocean in a way that seems to have strengthened their bond. The Drayton sonnet is about the complexity of separation and the fact that to separate from a lover is not simply to divide from another, but from a part of oneself. For me the ideas in that sonnet are at the emotional center of the entire Secret History project.

MacDonald: When I saw The Great Art of Knowing, I realized that I was (finally!) getting to understand your larger project.

Gatten: That was true for me too! I had been making each of these films separately. I knew they were part of a series, but when I started making The Great Art of Knowing, I began to see new connections between the films and how I could actually knit those connections together. When I first started working with the material that becomes the central section of The Great Art of Knowing, I didn’t think I was making a Byrd film. I had seen the exhibition of Leonardo’s drawings at the Metropolitan Museum in New York in February 2003 and was really taken with his handwriting, partly because it’s mirror-writing. Also, I noticed that whenever he was exploring something, he would write and he would draw in the margins; and the line between writing and drawing is very hazy in a lot of what he did—or at least it was for me because I couldn’t read the handwriting. I decided I wanted to work with this text in the same way I worked with the Bible texts in Moxon’s Mechanick Exercises: I wanted to lift the text from the pages; and I wanted to explore the lines of text and of the drawings as shapes that evoke language without revealing specific meanings: I wanted to think about the idea that, in order to understand something, you have to have both language and image.

I was particularly interested in the Codex on the Flight of Birds where Leonardo was trying to understand how flight was possible and how to make a flying machine. I thought I was going to be making a Leonardo film, but then it dawned on me that I was working with birds again. In his time, there were many puns on William Byrd’s name (his nickname was “the Black Swan”) and much involvement with birds: he built a garden to attract hummingbirds; he was a bird-watcher; and he wrote about birds. Also, Evelyn drew pictures of birds. So my experiments became a Byrd film, as well as a bird film.

Also, I already knew that I was interested in the Athanasius Kircher texts that Byrd had in his library: The Great Art of Knowing, The Great Art of Light and Shadow, The Ecstatic Heavenly Journey. I started reading about Kircher, and somehow I connected the text of The Great Art of Knowing, which is sometimes referred to as the first book of symbolic logic, to Leonardo’s attempt to understand flight. How is it, after all, that we can understand something? Everyone who I was reading at that moment was an empiricist of some sort, believing that through our senses we can accumulate knowledge. I started collecting different people who were looking at birds and trying to understand flight, and, of course, in time that brought me to Marey. Leonardo and Marey became my parentheses around five hundred years of people looking at and trying to understand the flight of birds.

MacDonald: A question about the exhibition of the films in the Secret History project. Moxon’s Mechanick Exercises and The Enjoyment of Reading are meant to be shown at 18 frames per second, but Secret History of the Dividing Line and The Great Art of Knowing at 24 frames per second. Given the difficulty of showing at silent speed these days, why did you choose it for the first two films you finished?

Gatten: With Moxon’s Mechanick Exercises I chose 18 frames per second because I wanted the subtle flicker that the slower speed creates, and I wanted that text to move slowly. When I made The Enjoyment of Reading, I decided the project was going to stay at 18, but I gradually realized that this decision was creating a serious problem for most anyone wanting to show the films; it’s hard enough to find 16mm projectors these days, much less projectors that can show at 18 frames per second. So I’ve changed to 24.

MacDonald: Can you talk a bit more about the remaining films in the cycle?

Gatten: Another big film that has to be done involves the division of labor on Byrd’s plantation: slavery. Byrd owned thirteen other people, and that’s partly why he could buy all these books and spend so much time reading them. I knew I wanted to do a film on that, but for a long time didn’t know how, because there were no books in his library about slavery. But then I found Halfpenny’s Principles of Architecture, about how to most efficiently design your plantation—so division of space as it effects and conditions and produces the division of labor became my way into dealing with slavery and race. There’s good imagery in the architectural plans, including an image of the great house and its subordinate dependencies. That’ll be the seventh film, Halfpenny’s Principles of Architecture. The ninth and final film, The Ecstatic Heavenly Journey, will be the ghost story.

MacDonald: What’s the next film you plan to complete?

Gatten: The next one will be the fifth film, which will use Robert Boyle’s Occasional Reflections upon Several Subjects from the Byrd library as a guiding text. The Boyle book is going to be colliding with The Book of White Magic, published in the 1920s, basically to help unhappy women make sense of their lives. The book provides ninetyfive different questions; you choose a question and then close your eyes and point to a table of symbols and then use a grid to tell you what page to turn to, and the book will answer your question. The questions are wonderful and very poetic, and if you read down a page of answers, it’s a fantastic poem.

MacDonald: Sounds like the I Ching.

Gatten: Very much. So Gadbury’s Doctrine of Nativities, containing the whole Art of Directions and annual Revolutions: whereby, any man (even of an ordinary capacity) may be enabled to discover the most remarkable and occult Incidents of His Life will be the next film.