“While there are great benefits to digital technology, if you embrace it today, you are giving up guaranteed long-term access which you have with analog film.”

Milt Shefter, Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences, Digital Motion Picture Archival Project

Let me tell you: the more I’m getting involved in the whole audiovisual digitalisation business, the more confused I get. There’s not only the continuous going-back-and-forth between the issues of preservation of the past on one hand and anticipation of the future on the other (that might be the thing I’m having trouble with most of all), but there’s also the the difficult decision-making process, influenced and clouded by so many powerful, mostly industrial, forces. What to make of this, for example: a recent SUN Microsystems report estimates the cost of ‘digital film’ is about ‘half the price’ of analogue, while another report, published by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences, says it’s nearly ‘twelve times higher’! Of course, these costs depend on many complex variables and on their interaction (uses of the content, quality for digitisation, type of content, categories of users, etc.), but still.. it’s hard to make any kind of sense of this kind of ‘findings’, especially when it becomes clear that lots of industrial-based concepts are unsufficiently defined or at least ambiguous. To make things even more complicated, all eyes in the cinema business might be directed towards the digitalisation of film, but this kind of blind all-digital push-mentality might destroy more than we can imagine. An European research project, called FIRST (FIlm Restoration and conservation STrategies), published a few years ago, was not only unable to quantify the costs involved in the digitisation of large collections of film materials, but also conluded that digitisation is NOT a preservation strategy for film, at least not yet: film remains the safest carrier for high quality, high value film content. There are so many misunderstandings about this, even in the professional areas of cultural heritage, so again: digitized content does NOT replace the analogue film original, which means (the cost for) digitalisation is in addition to activities in the analogue domain.

Digital preservation sets out to preserve the “shape and substance” of images or sounds without preserving the format, or the support…. or the original experience. Is this acceptable for film, which has its particular “look and feel” that has inpired, and keeps on inspiring (f.e. there seems to be emerging a new generation of 8mm and 16mm filmmakers. Go to any ‘openminded’ filmfestival and you’ll notice) so many wonderful forms of cultural expression and experimentation? Archivists are widely divided, but would, in the end, agree that it is better to preserve what is possible, than lose a film image entirely. Furthermore, restoration of film can only be done in a optimal fashion, if the original film image is retained. Surely, analogue restoration is often extremely labour- and time-consuming and therefore very costly, and only a few films get the full restoration treatment to the degree that they deserve or need, but then again digital technology is not expected to be cheaper and will definitely not increase the numbers fully restored. Technology companies claim that they have achieved efficient single-image compression schemes (spatial or inter-frame compressions) that are indistinguishable from uncompressed images, but let’s not forget that these compressed images, in effect frozen in time, use, space and quality, can’t be worked on again to improve a restoration or extend quality to provide an new access version for an improved projection system – and technology always keeps improving.

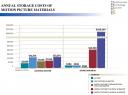

So film is here to stay, at least untill further notice, and it cannot be discarded just because its content is digitized for today’s access on DVD, for VOD etc. Of course, the advent of these digital delivery modes and channels offer unprecedented opportunities for film collections to provide access to their holdings, so digitalisation is still worthwhile, particularly in a context where the traditional theatrical screening model is not responding to a growing demand anymore (According to data published by The Hollywood Reporter, only about 19% of total revenue for the six largest movie companies came from theater showings. The remaining 81% represents revenue generated through DVDs, TV, pay TV and VHS. Let’s hope the traditional film theatres survive, especially the smaller ones. I wouldn’t wanna miss the magic light and sound of filmprojection). But the management of this proces, as well as the cost structure, is extremely complex (see image), not in the least because an important part of the process must take place long before the content is actually transferred, and some of the most critical deeply interconnected decisions influence the whole process. These strategic decisions, for example the mode of distribution and delivery, will decide the resolution and technical characteristics of the digitised content, or the selection of the content to be digitised, and these are positioned all along the chain. This is complicated by the fact that you have literally dozens of ways that a piece of content can be viewed, depending upon the licensing rules, from theater to mobile to broadband to any number of devices in different formats. The methods and processes by which they go from higher resolution to lower resolution have to become increasingly more efficient.

Sure, more and more filmmakers shoot their movies on digital cameras and perform post-production on computers; the studios distribute the films to theaters via hard drives, tape drives or satellite; and then cinemas show the films using digital projectors. So that should reduce the problems, no? NO way. In the AMPAS report mentioned (“The Digital Dilemma: Strategic Issues in Archiving and Accessing Digital Motion Picture Materials”), the authors point to the facts that current 2K digital quality is inferior compared to 35mm film, that digital storage media has a shorter lifespan than film, and the annual costs for preserving film archival masters ($1,059 per title, $8.83 per running minute) is still (at least according to them) a lot cheaper than preserving a 4K digital master ($12,514 and $104.28). Much worse, to keep the enormous swarm of data produced when a picture is ‘born digital’ pushes the cost of preservation to $208,569 a year, vastly higher than the $486 it costs to toss the camera negatives, audio recordings, on-set photographs and annotated scripts of an all-film production into the cold-storage vault. One case study states that a two-hour feature film would take up about 129 cartons or cans, which are normally stored in vaults often located in underground salt mines. “Nobody paid any attention to what the budget was because it wasn’t significant,” says Milt Shefter, the project leader on the AMPAS Science and Technology Council’s digital motion picture archival project.

To make things worse, there’s also the amount of information that is generated nowadays. While a director using 35mm film might shoot 15 or 18 minutes of film for every minute used in the final movie, “that ratio goes up tremendously when you go to digital,” says Shefter. “It encourages more use.” For instance, because film doesn’t need to be loaded into the camera, the cameras just keep shooting – even as the director steps out from behind the camera to talk with the cast. Adding to the amount of data created in the making of a typical movie are the files generated during the post-production process, when the footage is turned into a sellable product. Directors believe they have better control when the movie goes to digital. “You can do so much more in the post-production process in digital than [you] were ever able to do in film,” says Shefter. As an article in Computerworld states: “the bottom line is that movie studios are in a position of having to maintain hundreds of terabytes of data for the material associated with any single motion picture, content that’s barely or rarely cataloged or indexed”.

In an article titled “The Afterlife is Expensive for Digital Movies” the Times says that all (blockbuster) movies, including all movies shot in digital, are still preserved onto analog film “At present, a copy of virtually all studio movies — even those like ‘Click’ or ‘Miami Vice’ that are shot using digital processes — is being stored in film format, protecting the finished product for 100 years or more.” Not that the traditional film storage is so great, considering that “only half of the feature films shot before 1950 survive”, and lots of film is rotting away in archives worldwide (remember that broadcasters such as the the BBC, for example, are known to have destroyed or erased many of the programs saved in its videotape and film libraries to make room for new programs). But at least, that we know, while the questions and concerns about digital storage are still very much unknown, as Shefter says: “To begin with, the hardware and storage media — magnetic tapes, disks, whatever — on which a film is encoded are much less enduring than good old film. If not operated occasionally, a hard drive will freeze up in as little as two years. Similarly, DVDs tend to degrade: according to the report, only half of a collection of disks can be expected to last for 15 years, not a reassuring prospect to those who think about centuries (The question of the long-term reliability of disk storage was the topic of many studies, see here). Digital audiotape, it was discovered, tends to hit a “brick wall” when it degrades. While conventional tape becomes scratchy, the digital variety becomes unreadable.”

Now acetate-based films and their related materials are more likely to be archived in climate-controlled facilities with fire suppression systems, where film master can be preserved up to 100 years and more. Digital tapes and disks that have replaced acid-free cartons and steel metal cans used for film “have not proved to be a significant successful method of preserving this information.” Some users reported to the AMPAS that the materials on the drives couldn’t be accessed after only 18 months. For example, LTO4, the current standard for tape drives in the movie business, which became available in 2007, is unable to read the contents of tapes written in the LTO1 format, the standard in 2000. “If you’re dealing with a technology where you have to make a decision about what to do with it somewhere within a four- or five-year period, you have to know you’re going to migrate it [or] get rid of it,” explains Shefter. The studios’ solution: to generate the majority of the revenue in that period before they have to make migration decisions. The academy’s report also mentions some examples of the so-called “triage on the fly” process. Broadcaster ESPN (Entertainment and Sports Programming Network) for example runs a huge server farm where, after a week’s collection of broadcasts came in from professional and college sports, somebody – usually an intern – would go in and erase much of the data to make room for the next week’s broadcast content. “That’s a microcosm of what is going to happen in the industry,” says Shefter.

“We are already heading down this digital road … and there is no long-term guaranteed access to what is being created. We need to understand what the consequences are and start planning now while we still have an analog backup system available.” Shefter notes that a requirement for any preservation system is that it must meet or exceed the performance characteristic benefits of the current analog photochemical film system. According to the report, these benefits include a worldwide standard, guaranteed long-terms access (100-year minimum) with no loss in quality, the ability to create duplicate masters to fulfill future (and unknown) distribution needs and opportunities, immunity from escalating financial investment, picture and sound quality which meets or exceeds that of original camera negative and production sound recordings, and no dependence on shifting technology platforms. If these terms can’t be agreed on, the data explosion could well turn into digital movie extinction…