Two interviews. The first was recorded by Enrico Ghezzi and Roberto Turigliatto in June 2001, and published in Italian in the catalog of the Debord retrospective at the Venice Film Festival. Reread, corrected, and completed in March 2002 for the catalog of the retrospective presented at Magic Cinéma in Bobigny. English translation by Chris Fujiwara, as found on fipresci.org. The second was recorded by Brian Price and Meghan Sutherland, and published on worldpicturejournal.com in spring 2008.

1

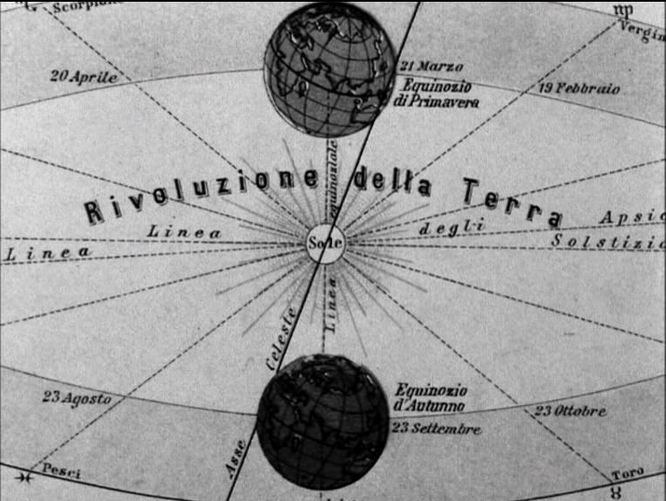

It’s very tricky to talk or write about Debord, in the sense that his is the work that lends itself least to analysis or commentary. That’s why, for me, there was a sort of immediate necessity to write on him at the moment of his death. It seemed to me that I needed to say something at that very moment, and I felt I could say it in a way that was precise, clear, and very detailed. I say that Debord’s work is difficult to discuss in the sense that it is entirely built on the instant. There is always this idea, in Debord, of saying things that have to do with the present time, that are instantly verifiable and relevant. They have to do, of course, with something that has value in time, the global value of the analysis of the society in which one lives, but their strategic value is always — and this seems to me to be the very basis of Debord’s thought — linked to the instant itself. Next — beyond that, or parallel to that — there is Debord’s poetry, his way of looking at the passage of time and at the vanity of things, that eternal truth to which he is profoundly connected. And this is, all the same, the essence of his artistic work, in the reductive sense of the term. But his philosophical work and his artistic work are always preoccupied with clarity, with precision, and with the link to the world as it presents itself to him at this moment. I always have an impression that discussion of Debord is a way of withdrawing his work from specific time (which is a time that Debord has defined and drawn) in order to put it into the much more indistinct time of reflection, analysis, or commentary, a time that always risks being either academic, or else placed within a kind of literary history to which he never wanted to belong. For my part, I had the feeling — at the time when Debord’s work was being published by Champ libre — that it existed in a territory that was his own, in terms which were Debord’s, in fact it was a kind of meta-edition. There was not just the work in itself, but also a very coherent affirmation concerning the way in which a text should be circulated, how the force or the veracity of that text are equally linked to the conditions in which it is published. This also had to do with why Champ libre chose not to publish a pocket edition, not to send review copies, to be a political and artistic act within the world of publishing. Obviously, once Debord’s work passed outside this unique situation of control and rigorousness, once it reentered the classical circulation system of publishing (Gallimard is, after all, a very good posthumous publisher for Debord), the work loses something. I don’t think my viewpoint is excessive or unfaithful to Debord’s memory; I’m sure that he himself would have looked at it that way.

Anyway, it was his choice, and he made it knowing that it would give him greater circulation, but above all that what was in a question was a second time for his work. After the present — for a work whose relation to this thought of the present was of such density and a total rigorousness — there is a second time, which is that of history, of posterity, whatever you want to call it. The way his relationship with his first publisher evolved, and then the fact that at a given moment there was, simply, the need to find another one, also had to do with the prolongation and the qualitative transformation of his work. The new edition of his writings, on a different terrain, has produced in turn misunderstandings of a new and different nature.

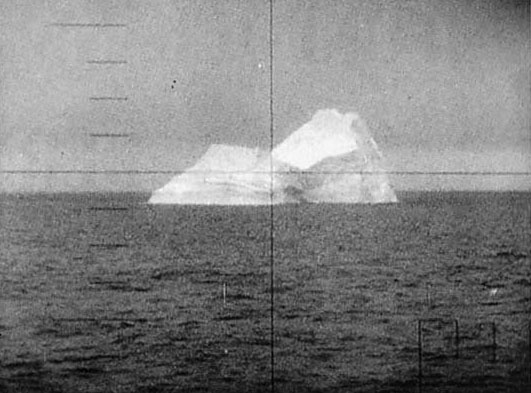

That, in any case, is what the book Cette mauvaise réputation deals with, it’s the very object of this book. And thus, the question I’m asking — a purely academic one, by the way — is: what will be the exact nature of the transformation of Debord’s films, from their very special status of rarity to their status of visibility? From whatever point you take up Debord’s cinematographic work, it is built around an extreme singularity. It’s a work that is immensely admired by the rare spectators who have seen it, but which also has a kind of aura — in Walter Benjamin’s sense — that is specific to being a hidden work. I think that the artistic act, the aesthetic act of Debord’s cinema is, in part, also defined by this choice not to be shown, in a time when all images present themselves as having to be shown. The radicality of his approach is linked to this act, a remarkably violent one in the world in which we live, of hiding one’s films for twenty or thirty years.

His films were literally no longer shown anywhere after 1984, and were not much shown before Gérard Lebovici bought the Studio Cujas to show them continuously. These are films that are parallel to the history of cinema and that are the inverse of it, the negative of it, whatever word one wishes to use. So there is going to be a kind of transformation or transubstantiation of this cinema, from the moment when it becomes accessible and visible. What effect and what violence might be caused by this eruption of Debord’s cinema in our reading of contemporary cinema? These films are milestones in the history of modern cinema, but that wasn’t recognized; and so, as a result, are they going to give rise to a re-reading, or will they simply be classed in the dictionary next to other works? Will they keep their intrinsic aura and radicality, or will they be classified alongside other works of experimental cinema, if not placed somewhere between the cinema that is shown in museums and the films of Jean-Luc Godard, for example?

2

The strongest and most intimate feeling that I get from Sur le passage [de quelques personnes à travers une assez courte unité de temps] and Critique de la séparation, which I’ve just watched, touches on the coherence that they reveal at once. These are two essential missing milestones in the knowledge and understanding of Debord’s trajectory. There are two works that are completely linked: Mémoires and Hurlements en faveur de Sade. It could be said that Hurlements en faveur de Sade is the cinematic counterpart of Mémoires. It’s very strange, how Mémoires was eventually read, somewhat, at the time of its republication, and yet it has not been placed as it should be in history. Mémoires is one of the great books, one of the masterpieces, without doubt, of contemporary French poetry. Myself, I put it very high, it’s an overwhelming, magnificent text. If the trouble were taken to situate it in its context, it seems to me that it would be very illuminating, including in terms of our perception of the poetry of that period. And when you see Sur le passage and Critique de la séparation, it becomes clear that that poetic vein of Debord goes on and very quickly transforms itself into something new.

I used to situate this deployment of his poetry in cinema much later, to the extent that for me, In girum [imus nocte et consumimur igni] was its moment. Actually, it was, above all, its qualitative transformation. The mistake was, of course, to see In girum in relation to the other Debord films that I knew, that is to say, La société du spectacle and Réfutation de tous les jugements.. I thought that basically In girum began a melancholy, introspective vein, which would be continued with Panégyrique, especially. But really when you see the short films it becomes clear that this vein was there from the beginning, this melancholy, the sense of the passage of time, this central notion of Debord’s thought was already there, in raw form. It’s there in raw form in Hurlements en faveur de Sade; it’s there, in similarly intense terms, in Mémoires, six years later, and it’s there — let’s say — internalized, commented on, and mirror-reflected in Sur le passage de quelques personnes à travers une assez courte unité de temps.

That film, shot in 1959 and examining the validity of reproducing, six years later, events and situations that took place in 1953, is in the same relation to that moment of poetic intensity that In girum was in later. And in reality, they are already films of summation, retrospective films, on the difficulty that cinema has in seizing, reproducing, or stopping time. That’s why they touched me very much. Is it in In girum, or in Panégyrique, that Debord says: “but what aroused displeasure in a very durable way was what I did in 1952”? I find that magnificent because that’s exactly the moment of his poetic work, it’s the year of Hurlements en faveur de Sade, it’s a moment of absolute harmony among his poetry, his political vision, and his life. Everything comes together in an instant of his existence to which he will go on referring constantly. He always returns to that period when life gave the feeling of being fully lived. Debord had an extraordinary lucidity about the importance of this unity of time, not just in his life, but philosophically and intellectually in the history of postwar French art.

The question is: what can one build on top of ruins? For me, I’m fascinated by the people who restarted cinema from zero. It’s for that reason, no doubt, that I’m very responsive to Warhol’s cinematographic work, because Warhol, in a different way, began making film by starting with nothing: he decided that at a given moment there could be a zero point of cinema. And in a certain way, Debord himself established that zero point. Again, everything he says should be taken very seriously. In Il girum, he affirms — I’m paraphrasing very badly — that making an important work in film took him relatively little time and effort. It’s very beautiful because it’s entirely true.

In the film theory of that time, faith in a kind of ontology was a way of saying that film was an art. But all that was very late in comparison with how the very nature of art in painting and the plastic arts in general, which were blown apart by Dadaism, was put in question. Film had not met its Dadaist moment, its moment of having its system of representation and exposition submitted to an absolute questioning. And when Debord makes Hurlements en faveur de Sade, he has in mind, I think, very literally the idea of making the Malevich’s White on White of film. Hurlements en faveur de Sade is Malevich’s White on White, with the same (it’s hard to find words that he wouldn’t have disliked) spirituality as in Malevich. The ambition, the spiritual inspiration that we project onto the intention of Hurlements en faveur de Sade is identical to those that we project onto White on White; this timely vertigo, in the sense of accomplishing an act that, beyond being a painting, is a moment in art history. White on White isn’t a pictorial genre of its own; Hurlements en faveur de Sade isn’t a cinematic genre. It’s a cinematic gesture that can be considered a milestone.

In the very matter of all arts, whether it be literature, music, or film, it seems to me that there is always a poetic core, a very dense matter, that is at the heart of things and from which the rest radiates. In Debord’s work, this core of poetry — in the strongest sense of the term, that is to say, in the sense of the poetry of the greatest poets — is in Mémoires and Hurlements en faveur de Sade. These are works that can exist only in a moment of grace, in a moment of privileged intensity. In the same way that, when Isidore Isou makes Traité de bave et d’éternité, it’s the work of a 23-year-old poet who makes one film and then nothing more, in any case, nothing more of that value, of that intensity. There is this faith of believing that art is an extremely acute way of restoring the truth of an exceptional moment and that the most important, the most superior art works are those that take account of that instant, that seize it and have no descendance, cannot have any.

In Debord’s work, there is a second aspect, which is that of literary détournement or collage (one can call it whatever one wants; in literature, what he did before others did it has been called collage). At a given moment, literary collage turns into the thought of cinematographic détournement. It is expanded on in Sur le passage de quelques personnes and in Critique de la séparation, and then, in a certain way, it is completed with the film La société du spectacle. The starting point is the question of how to reconstruct a cinema starting from the zero point: what cinema can be made after Hurlements en faveur de Sade, it’s a little like defining what poetry can be made after Mallarmé, or what novel after Proust, to speak of works that are metaphysical upheavals from the very point of view of their own essence.

Debord’s artistic, intellectual courage lies in not retreating from that question. He could just as well have stayed at Hurlements en faveur de Sade, but at the same time he knows that it’s not enough to make a tabula rasa, you have to know what you’re going to build, what is still possible in this art and how, once you’ve reached that point. There is a way of examining film, of examining art through, precisely, its limits in its ability to reproduce the past, the difficulty it has in rendering the confusion of the world. It’s this that I find very beautiful in the two shorts (it’s Critique de la séparation, I think, that starts specifically with this idea), that cinema is built on a way of reorganizing the world; so if one really wants to take account of the world one must first of all be able to render its confusion, its contradictions.

The aim of Sur le passage is exactly that, the inability of film to reproduce truth, the truth of an instant, an inability that results from its particular nature of delay. At the same time, perhaps, film can serve to put that loss in perspective. Sur le passage is the starting point of a large part of Debord’s cinema. It’s there that it becomes clear that, in a certain way, film takes account of loss. If film is incapable, precisely, of taking account of the instant, since the instant can only be miraculously preserved by artistic lightning-strokes, it can, on the other hand, restore the melancholy of its absence. And melancholy is Debord’s subject, the flight of time, always, always, always. And I think that he becomes aware of it himself when he makes Sur le passage; after that his cinema will be nothing more than the celebration of this flight of time.

3

I don’t compare Debord with Warhol from the point of view of their artistic approaches, which have no relation with each other. What links them is the fact that Warhol takes up American cinema again practically from zero. When he makes Sleep, and his first films, they’re in black and white and silent. He starts by making static images of objects or of John Giorno sleeping, and then, progressively, sound appears, then speech, then color, two screens. Next he has the idea of building canvases inside these moments, and he reinvents the notion of the actor. He says, “I’m not going to use professionals, I’m going to take people who are themselves actors of their own lives, who are themselves in representation, and that should be enough to make a film character.” And we come to his last film, Lonesome Cowboys, which ends up being a narrative film in color. After that he stops. Let’s say, without being mean, that from that point on Paul Morrissey more or less liquidates Warhol’s cinema, he sells what there is to sell.

What is very beautiful in Warhol’s cinema is this movement, I think between ’63 and ’68: in five years he goes through the entire progress of film, and when he reaches the point where film is, when he becomes synchronous with American cinema, it no longer interests him. To the contrary of Debord, his cinema is completely documentary. He thinks that he can capture beings, that he can catch instants in their flight. These are films in which he captures in a documentary manner something that is in the process of really happening around him, individuals who are permeated by the air of time, in the most literal sense of the term. Debord isn’t interested for a second in the documentary value of the image. He doesn’t believe in it at all. It’s one of the main singularities of his cinema. In general, with Debord, when there are eruptions of the truth, it’s in photos. When he shows Asger Jorn or other close friends, it’s always faces, and they’re the same ones who return cyclically in all his films, till the end. In a certain way, those faces are truthful, they’re the real, the really documentary instant. For example, the café scene with Jorn, himself with his arm around this girl’s neck, and so on. it’s a posed photo, but because it puts into play a reality, incarnated by the beings who have taken it on, it becomes truthful de facto, it truly captures the instant, and does not pose the problem of the reproduction of the instant. There’s this idea that as long as real life is experienced by beings in poetic moments that have an intrinsic poetic value, the camera can’t be there because it blocks them, which is profoundly true. On the other hand, photography can be a shadow of that instant, whereas film can have the capacity to evoke its memory. Just as music — outside time — restores its soul, putting it back within the eternal return of human passions, always that music of the 17th century, which has this kind of nobility and melancholy, at the same time this joy, this spirituality and this metaphysical sadness which also belongs to Bossuet. What also struck me about the two short films is that they don’t come out of a will to control. They are films that expose their vulnerability. Debord himself questions himself about what he is doing, about what he is saying, the limits and ambitions of what he is trying to grasp through these films. They are films in which doubt is integrated, included, and not just concerning the way they might be understood or seen. I have the impression that this is a dimension that is absent from the other films: when, later, he makes La société du spectacle, and even, all the more so, when he makes In girum, he has found a form. In the two shorts, this idea of cinema is literally in search of itself, it’s someone who is in the process of inventing, before our eyes, a cinematic language. In the end things need to be put back into their context; let’s admit that a film like Traité de bave et d’éternité showed the way; in any case Isou’s image appears in Sur le passage. Later, in La société du spectacle and in In girum the syntax is there, Debord has invented his own cinematic language and suddenly this language opens up: it has the ability to absorb new things and take hold of new dimensions. Particularly through the use of film sequences, which are then, strictly speaking, détournements, which sometimes have the same place or the same value as the citations, the text détournements that he practiced starting with Mémoires.

Debord is the only representative of an idea of film that has been neglected. He asks himself the question of whether or not he is the precursor of something. In any case, he uses film for different reasons, and in a different manner, from what film progressively became, and even from what he was searching for in a period when work of experimental reflection on meaning or on the use of the other cinematography was more on the agenda than it has been at other times.

So, is it a proper way of putting things, to compare Debord’s cinema with the New Wave? It’s a real question, a complicated question and one which has to do with the nature of film and the profound relationship of cinema with the other arts. I myself tend to think — it’s my experience and my practice as a filmmaker — that film stands apart from the other arts. I don’t know if it’s an art or if it’s not an art. anyway, it’s certainly an art very different from the others, in the sense that it has this capacity of documentary recording. A film image is made, and, instantaneously, it’s the documentary of something: the more or less adroit way that a group of people go about reconstructing a situation whose nature they know or don’t know. That’s almost a kind of definition of a film image. But this documentary aspect makes it happen that film can also be a witness of the other arts, it can put them in perspective. I always have the impression that film isn’t preoccupied with the same interrogations as the plastic arts, but that in the best of cases it can take account of those interrogations, it can serve to document that history. Godard has been the privileged representative of this whole debate. Godard was the one who asked himself the question of how to place film in relation with modern art, while moving away from the Bazinian ontology of film — an ontology that doesn’t make room for that reflection. Film in an examination of perception, film in an examination of itself as an art: these are two completely different things. Godard is on the side of the examination of film as an art, in the same way that Debord is. But — without calling Godard’s work into question — Debord stands for this examination in a more essential and more profound way. With him, cinematographic acts, their chronology and their value, are decisive.

4

With the circulation of the films after Venice a transmutation in the nature of the works is going to happen, in that today, at the moment when we’re speaking about it, in June 2001, Debord’s cinema is in part constituted by the aura of its invisibility. Debord’s artistic, cinematographic gesture is inextricably linked to the invisibility of his cinema; it’s an act of supreme radicality. The fact that these films are now going to be shown doesn’t throw into question the artistic importance of having hidden his films. Having chosen not to show them anymore is (like everything Debord did) an incredibly relevant and profound artistic choice. Now that act is going to belong to the past. Today, the invisibility of these films is the last artistic gesture of Debord’s with which we are still contemporary, in its total purity, and after Venice, it will be talked about in the past tense. We’ll be able to analyze the invisibility of Debord’s films, we’ll be able to discuss the films while integrating in a theoretical way the fact that they were invisible and withdrawn from circulation, but we won’t be able to talk about them anymore with this intimate feeling that is aroused by their rarity.

The relationship that I was able to have with this cinema, the feeling of having been one of the rare spectators of a remarkable event, an extraordinary event, the uniqueness of the experience of knowing these films and being inspired by them — well, very simply, all that is going to be lost because these films will be seen and distributed; and people will mis-see them, just as one can observe today that very often Debord is misread, even by people who often admire him. By people who perceive one of the dimensions of his work but not the totality: those who appreciate the poetry of his work are less sensitive to his thought, or to his philosophy, and those who appreciate his philosophy understand nothing of his poetry, and neither of the two understand a thing about his cinema. Today there is a supplementary piece of the puzzle that is going to be brought to light, and perhaps in that visibility it will no longer be seen, because one of the characteristics of the things that are plainly visible in today’s world is that they are not seen, while those that are invisible create an effect of magnetization, of fascination, and also of truth (not that this keeps them from having the power to deceive). Everyone feels very clearly that there is something very right, very true, and very authentic in not wanting to be seen in today’s world: these films are the final testimony to this. I feel a real melancholy, a circular one, because it’s one that resembles the melancholy that comes from the films, in the fact that from now on these invisible films are going to be visible; personally, I liked the idea that there could be hidden masterpieces, that someone could not want to show such very great films. That idea is magnificent and incredibly relevant, at once politically, intellectually, and artistically. It’s idiotic to say that I would rather these films were not seen, but at the same time I know that the films will lose something by it, something of what Debord had wanted them to be. In short, that they are entering another time.

But why weren’t these films seen when they were visible? That’s a completely different question, which is much harder to answer. First, it’s necessary to return to the context of the period, when Debord was very little read. Today everyone talks about nothing but situationism, it’s as if everyone had always read Debord and known his theses, as if the obviousness of the importance of situationism as an artistic or intellectual movement had always been recognized. But really it was a minority within the minority, it was quasi-invisible. It’s only today that people are willing to say that situationism was at the heart of May ’68. For twenty years after May ’68 no one was saying that, that thought was really inside the margin of marginality. I’d be curious to know what the print run was of the Champ libre texts, including those of Debord. At the time, no one even wanted to reconsider Debord’s cinematic work. On the jacket of the first Champ libre edition of La Société du spectacle, if you remember, there was a kind of biographical note written up by Debord, saying about himself: “calls himself a filmmaker”. it’s magnificent! At the time people were saying: “what, he made films?” No one took him seriously, there was no curiosity. His films were denied. It’s interesting to see, through Réfutation de tous les jugements., how the press received La société du spectacle when the film was released.

At the beginning of the ’80s, almost twenty years ago, no one wanted to see them, no one wanted to go to the Studio Cujas and ask themselves the question of what the cinema of Guy Debord was. It’s a little bit exaggerated, but I think that at the time, the Studio Cujas had more or less the kind of status that a cinema would have that showed continuously — for example — the work of Maurice Lemaître or of Marcel Hanoun. A picturesque phenomenon, a demonstration by an exotic sect. It made people laugh, the fact that Debord’s films were shown continuously at the Studio Cujas. No critical article appeared in the press or in magazines. None! That was consistent with Debord’s invisibility at that time. The general ignorance concerning situationist thought was dizzying. Afterward, very slowly, things turned around, and now people have the impression that it was always there. In a certain way, how situationism was perceived then is like how Lettrism is perceived today, some kind of rather pathetic avant-garde sect that outlived its time, with no relevance to the vision of the contemporary world. At the time, people had the feeling that it was just one of the dead ends of modern art. Or else one of the multiple esoteric subdivisions of leftism.

5

In Debord’s work, art has meaning only if it’s linked to practice, to existence, to life, in an intrinsic manner. Works of art have value only as restitution, as traces of lived experience, and only if the implication of the artist in the work is complete. That’s why I insist strongly on the idea I spoke about, that books or films are not just books and films, they also have value in their perfect coherence in their relationship to publication and to production, in the way they are circulated. It’s exactly for that reason that Debord published the texts of the contracts for his films.

If you look at Debord’s work as it was preserved by him during his life, it has a limpid clarity, an absolute purity. Everything responds to everything else, everything is in a system of correspondences all of which have to do with the central notion of his work, the idea of going beyond art. Going beyond art lies in action, in this case, an action on the world; poetry in action is revolution, the transformation of the world through a questioning of its values, of its functioning, in the name of a superior idea introduced by poetry. I’m using words that Debord wouldn’t have liked much, but they’re the simplest ones to use in accounting for this experience.

Each of the films is conceived at once as a poetic act and as a political act. It’s a question each time of posing, through this work, a defiance to the world, a defiance to the system. Each of the films, in its own way, asks the question of what is, at this moment, all the rest of cinema, all the rest of political thought, all the rest of poetry. In this capacity for solitude and for the solitary affirmation of an intimate truth, there is a way of being that is obviously the very essence of the most important part of what is done in art. In the case of the two short films, it’s very striking, the extent to which, today, these lost, forgotten films that were invisible for twenty years — but not really seen for forty — return to us and suddenly reach us, they touch us, they move us all the more for belonging to a solitary voice, to someone who was talking in the void forty years ago. Suddenly, they have this rightness, this obviousness, this modern beauty that can be seen in a limpid state today and that was invisible at that time. Debord believed that there was a truth to say, and that if his time was unable to see it, to feel it, well then, tomorrow those people who will have been raised up by the world as it was in the process of being transformed at that moment, will be able to see and understand it. It’s a marvelous wager. The trajectory of his films and the way that they have come to us are pretty unique experiences.

Debord’s meeting with Lebovici belongs to another time, another epoch; it’s the relationship between an artist and a patron of the arts, in the best sense of the term. It’s something completely unique in film and in contemporary art, at once very beautiful and completely anachronistic. That’s also because of the puritanism in France regarding money. The little that people understood of situationism was that there was no ideology of mistrust toward money and no complacency regarding poverty. It was very provocative and very much a break with the very conventional prevailing ideology of leftism. Still today, by the way. Money is made to be spent. In situationism, there is the artistic idea of expense (already in the notion of potlatch), of jouissance, money is there where it is and you take it; this situationist mythology was at once fascinating and irritating because freedom in the relationship with money is always judged from a stingy point of view. But in Debord there is no stinginess, and above all with respect to money; on the contrary, there’s an indifference to its use and its circulation. Thanks to Lebovici, Debord could make his films, his films could be shown, and Champ libre could be what it was. The editorial activity of Champ libre is indissociable from Debord’s work. In the Champ libre catalogue, even if Debord partly rejected it, there’s something that is the emanation of his thought. In a time of terrible ideological puritanism, Champ libre published classics that for a long time no one had read any more: Omar Khayyam, Vittorio Alfieri, Li Tai Po, Baltasar Gracián, Karl Kraus, Carl von Clausewitz, George Orwell. Through publishing, there was something of Debord’s openness of mind, his artistic and literary curiosity. He loved poetry, he loved writing, and he had a deep generosity toward works that, by their intellectual and human dignity, made a spontaneous echo in him.

The current vulgarization of the name of Guy Debord means that some of the situationists’ ideas are being recycled in a kind of postmodern pap. He’s been linked to the posterity of surrealism, or else to that of Dada, to that of the architectural utopias of the ’70s — so many interchangeable masks that can be used in this sort of postmodern globality in which everything is emptied of its meaning and everything is no longer anything but a game of appearances. Today people are so thrilled with the notion of radicality that they’ve forgotten what that meant. Radicality means taking the risk of being invisible, of not being seen at all, of being hated. Debord’s whole work was built on that, and in a certain way, the power with which it reaches us today also comes from its invisibility, or the earlier misunderstanding. And why do we have the feeling that it’s truthful? It’s truthful because it was hidden. It’s not difficult, it’s very easy, but no one has the courage to do it. The essential thing with Debord is the homogeneity and the absolute harmony between theory and practice. For Debord, it’s a matter, in effect, of going all the way to the extreme of an idea of art, or an idea of life, or how that idea of life and that idea of art come together, simply to demonstrate that there is, in that, a possible way. I don’t have the feeling that Debord claims to be a model or wants to give anybody lessons; but there is simply this need to search, within himself and for himself, for the absolute of coherence in his reflection on the world and more precisely the transformation of the world before his own eyes. From this point of view, it’s up to everyone to decide what to make of this example, up to everyone to make what one likes of one’s own practice, in relation to one’s own thinking. Today, as people become more and more agents of the integrated spectacular, they think they can be in activities, in an employment, or in a practice of the world that is absolutely opposed to what they really believe, whether ideologically or artistically. For someone to have imposed on himself his whole life long the rule of being absolutely in accord with himself, in his acts, in his life, and even in the ultimate extremities and consequences of those choices, this is something that is part of Debord’s work. Fundamentally his life is a kind of meta-work, his work tests his life totally, superimposes itself on it all the way until his suicide, and it’s in this that he is one of the most important artists of the twentieth century. I think Debord answered a question that is central in the questioning of art in the twentieth century. How does art match with our practice of the world, or how does art remain possible in the contemporary world? That’s the question left hanging by Tzara, by Breton, which was at last formulated in its real terms and resolved by Debord. He answered for himself, he gave an answer, his work, which is here, which looks at us, and which judges us.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Brian Price (BP): When did you first encounter Guy Debord?

Olivier Assayas (OA): I never actually met him. I suppose I was gradually attracted to the ideas. It has to do with France in the 70s, with the ambient of French leftism. That’s when I grew up. What is not clearly understood now is that you had different streams [at that time], in the sense that May ‘68 was not specifically a leftist event. There were some leftist groups that somehow later appropriated the event—like Maoists or Trotskyists—but to the core it was really a libertarian movement. And once you look into it, you can very clearly trace it back to some libertarian opposition to the communist, leftist ideology within the French university at that time.

I was thirteen in May ’68. My father had been a militant anti-fascist in Italy when he was a young man, then was close to “Communist” circles in Paris before the Second World War. But when he fled France, because of the anti-Semite laws in 1941, he ended up on the same boat as Victor Serge. Victor Serge was a prominent critic at that time of the totalitarian revolution of the Soviet Union. I suppose that my father became close to him and was certainly influenced by his ideas, which, of course, made him break with his ties to conventional Communism. He was also involved with the Free French [Forces], became a Gaullist, and after that became extremely anti-Stalinian. My mother was Hungarian. Her family fled Hungary once the Communists took over; they left everything behind. There was not much love for the Communist system in my family. My mother is something else. She never really discussed politics. She was not really into politics at all. But I grew up politically concerned, I suppose, but very far from the dominant ideology in France at the time. And here I am talking about the kids. They either had Communist parents who were blind to what was going on. We are talking about years when we had the Gulag—it was just horrible. It was the full totalitarian experience in Russia, and the kids were influenced by what was printed in the Communist press, which was very powerful at the time. These were the years when there was a 20% Communist electorate in France. That’s a lot of people. And then those who were not Communist were like post-Communist—Trotskyists or Maoists. Everything kind of blew up when I was a teenager, in May ’68. It has nothing to do with Communism, because I can see pretty clearly that all the Communist kids in my school hated it just because their parents hated it. They could only see it from the point of view of strikes, of getting better wages; the whole completely idiotic, reformist Communist trade union system. They were seeing things from a completely archaic point of view. They didn’t realize that there was something much more fundamental going on. The whole system was shaking. I had intuitions—of course, I don’t think that I would have formulated it that way—but I was kind of close to it. It had something to do with libertarian ideas, but also something else, which was not completely clear to me at the time. I realized, then, that there was a kind of leftism that was basically antileftist. So the whole event, of course, put things in motion for everybody. All of the sudden, people tried to build up their own political culture. They tried to understand where they were standing; you had to define yourself, even in terms of high school politics. Thanks to the lucidity of my father, I just never got into Communism, but still I felt very much connected to the revolutionary aspect of what was going on. I got more into trying to make sense of what I thought and how I related to what was going on.

The earliest thing that connected me to the ideas of the Situationist Internationale was the anti-Maoist writings published by René Viénet, published in his Bibliotheque Asiatique collection. He’s an interesting character. He was a Sinologist as a very young man. He started publishing writing that described the totalitarianism of the Chinese Communist system and described the reality of what had been going on during the Cultural Revolution, which of course, was absolute anathema in France at the time. Specifically the books of Simon Leys, Les habits neufs du Président Mao [The Chairman’s New Clothes: Mao and the Cultural Revolution] and Ombres chinoises [Chinese Shadows]. The leftists were okay to denounce Russian Communism to some extent, but only very carefully. It’s not like you could go to some leftist meeting with The Gulag Archipelago in your pocket. No way. Discussing China…this is period when you had the films of Antonioni. Antonioni was traveling in China and was filming whatever the Chinese Communists allowed him to see. Naïve western travelers. You also had movies by people like Joris Ivens. There were idyllic notions that Russia was wrong, but China was right. But the horror of it was that when you read about what was going on, it was even worse than what had been going on in Russia in the Stalinist era.

I was reading George Orwell at that time, Homage to Catalonia. A book like Homage to Catalonia, somehow, made me understand politics. Homage to Catalonia is about how Russian politicians manipulated the Spanish Revolution and how the libertarians resisted —which is slightly more complex because the P.O.U.M were not, strictly speaking, libertarians; they were anti-Stalinist Marxists, with a libertarian aspect. Orwell describes how they were eliminated by the Spanish Communists and how that led to the demise of the Spanish Republic. Orwell describes that so beautifully, so perfectly. The combination of my formative years, reading a lot of Orwell, and reading the anti-Maoist sinology published by Viénet led me to an interest modern cultural radical leftism that was much more connected with the present, with what was going on, with what I sensed was happening. And it was the reading of Viénet that led me to Debord. Viénet is very much a minor offshoot of Debord; ultimately, his anti-Maoist sinology is based on Debord’s own writing, which I only discovered later, because a few years before that he had published La point d’explosion de l’ideologie en Chine, [The Explosion Point of Ideology in China] which is ultimately the founding essay on the subject.

BP: Had you seen Viénet’s films?

OA: Yes. I had no idea of the theory of détournement that was behind it. I had no idea where they were coming from, but I just loved them. I saw La Dialectique peut-elle casser des briques? [Can Dialectics Break Bricks?] Later, I saw Chinois, encore un effort pour être révolutionnaires [China, Another Effort to be Revoultionaries], which is pretty good, actually, and then Mao par lui-même [Mao by Himself] . They’re very interesting.

BP: Where did you see them?

OA: They had mainstream runs, in art house cinemas. As you know, in France, there’s not such a strict border between the art house circuit and the mainstream. These were movies that were shown in the Quartier Latin, in the same circuit where you would see the films of the Nouvelle Vague. And they were fairly successful. You could see them. That, of course, led me to read La Société du spectacle [The Society of the Spectacle]. That’s also around when the movie La Société du spectacle was released. I think it was 1972 or 73. I didn’t understand most of it, I suppose, but it embodied the spirit of the time. I just so clearly connected with it. I had dragged my father to see it. I remember walking out of the theater with my father. My father was interested, but had no idea what it was about.

BP: Could you see at the beginning of your career the ways in which Debord, as both a filmmaker and writer, had affected your work?

OA: It influenced me intellectually. Artistically also, but a few years later—we’re talking 1981. In girum imus nocte et consumimur igni [We Spin Around the Night Consumed by the Fire] was released at that time and I had read over and over the re-edition of the Situationist International booklets. Debord published his Oeuvres cinématographiques completes [Collected Cinematographic Works] in 1980, I think, and then I read it. I had not seen the short films. No one had seen them. I had no idea—even remotely—what they looked like. I had read them and I loved them. And at the end, there was a text with a description of the new film. So basically, when it opened, I had already read the whole texts a couple of times. And when I saw the film, for me it was simply one of the meaningful modern works of art I had come across, at any level.

MS: It strikes me that you read these films before you saw them. You generally make narrative films, while the Situationists made a very different sort. Did you start out wanting to adapt these kinds of ideas to narrative cinema? Or did you think of making other kinds of films with them first?

OA: It’s complicated to make sense of. It’s a long and complex process. I first wanted to be a painter, so I started painting—between the ages of fifteen and twenty-five. Really, painting was at the center of my life. But I knew I wanted to become a filmmaker. At that time, I thought I could be both. Most of my painting was abstract and I suppose that in the back of my mind there was a notion that abstraction was for painting and movies were about characters and representing the world as it is, or something like that. But also, when I was twenty-one or twenty-two, when I realized that I could not do both things, I had a crisis. I kept on painting for years. But when I was twenty-one, twenty-two, it just became difficult to deal with both things on the same level and at the same time. And also, I had trouble with painting because I felt too alone. I just couldn’t handle, at that age, being alone in my studio, drawing, painting. And it’s completely addictive. You start working sometime in the afternoon and all of a sudden it’s dawn and you haven’t realized it. I was living in the countryside. My father had a house in the countryside. I was cut off from other kids and I thought that painting was cutting me off even more. So, I suppose it was at that point that filmmaking meant running away from abstraction, dealing with real, tangible things—establishing a relation with the real world and not just with ideas and abstraction, even poetic abstractions.

Also, to me, the work of Debord was extremely intimidating. Suddenly, it’s like you have the work of a genius in front of you and you’re very young. You’re not going to have the notion to emulate it. It’s just something that strikes you. But you want to do something else. It’s like all major works of art. They just encourage you to find your own way. It gives you the notion that someone has found his own way and has gone that incredibly far on his own way. So, it’s up to you at some point to define your own path and go as far as you can on that path. It’s always the relationship I had with artists that I admired: Guy Debord, Robert Bresson. I never tried to imitate Bresson; I never tried to imitate Tarkovsky, even though I worship them as filmmakers. So I suppose it also has to do with my experience of independent cinema—when I started questioning the notion of making film. I knew I wanted to be a filmmaker but I had no idea how you became a filmmaker. I had no idea what was going on really in terms of films. For instance, I worked for Cahiers du cinéma. I started writing for Cahiers du cinéma in 1980. At the time Serge Daney and Serge Toubiana had seen my first short film. They said “We want a younger writer, we want to change the magazine,” blah, blah, blah”. And then I went to the newsstand and I bought Cahiers du cinéma just so I could know what they were talking about.

BP: It’s interesting that you started writing for Cahiers during Daney’s time and that you felt conflicted about being both a painter and a filmmaker but not a filmmaker and a writer, especially in this more politicized moment of the journal.

OA: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Totally—it’s something that just happened. To put it as simply as I can, when I decided to make films, I understood that the one thing that was missing was writing. Pretty fast, I understood that to make movies with any kind of control over what I was doing, I had to have some kind of mastery of the written form. I would have to write screenplays. I would have to write dialogues that would make sense and that could be formulated by actors and I could not imagine being the kind of filmmaker that directed someone else’s screenplay. To me, that is not what art is about. Basically, I had learned what art was about when I was alone in my room with my box of colors. And I knew that process: you have the box of color, you have the canvas, and it’s just you in the middle. And that’s what art is about. So I could not imagine somebody else holding the box of colors or holding the brush or whatever. I knew I had to learn how to write. It was a very conscious process. I started taking notes, saying okay, this is my diary. I am going to write here every day. Then, it was really a stroke of luck that I meant Daney and Toubiana at the time because they gave me the opportunity to learn how to write by actually making it some kind of job. It was not paid like a serious job, but it’s kind of a serious job.

BP: Did Debord ever come up at the Cahiers offices at that time?

OA: No, not at all—not at all. It’s one of the reasons I had not read Cahiers du cinéma before, because to me they were boring, post-post Leftist, post-Stalinian. I had absolutely no intellectual affinity with them. How could I? They were translating things from Maoist publications. I opened the magazine and it just freaked me out. Jean Narboni is the nicest guy and a very smart man. But at that time he would write editorials discussing the cultural issues addressed by the leader of the French Communist Party, who was a real creep. Why are they wasting their time talking about this bullshit? They were publishing pieces by Pascal Bonitzer saying that Le Maman et la putain [The Mother and the Whore] was a perfect example of petit bourgeois individualism, or whatever. Junk! Junk! Just to go back a little. It’s also one of the reasons that when I first started to go into making films I didn’t go into abstraction, because I felt that abstraction in cinema was mostly Godardian. Everything around was half-baked Godardism, in one way or another. It became artistically and culturally suffocating. Somehow, the one thing that had been happening in those years, punk rock—The Clash, The Sex Pistols—gave you the notion that you just pick up whatever tools and make something on your own and just get rid of the past. In that sense, I felt that cinema hadn’t had its punk rock revolution. That French film culture was too much what I thought I had left behind via the punk rock event. The only way to be radical in cinema at the time was not to be abstract. It was by being figurative. It was by saying fuck you: I’m going to make a real movie with real characters, a real story, and ultimately I can say things through that medium that are stronger than whatever you are not even trying anymore to deal with.

BP: So often, punk rock of that period is only ever thought of in terms of its nihilism, but you’re really talking about its intense creativity, independence and world-making.

OA: Of course, of course! Music had become inconsistent. It had all been about virtuoso playing and art rock—bloated, empty and devoid of relevance. Then all of the sudden you had guys playing two-minute songs about guys on the dole, or just rebelling. You had the feeling of not being lost in the failures of 60s politics. What had started in May ’68—hope to change the world, hope of the revolution coming—had come to an end,

had become an empty shell. But these guys revived the very notion of facing society and expressing themselves in a way that is relevant, radical. It’s like within Hong Kong cinema when you had all those period pieces, all those sword play movies. All of a sudden you have Bruce Lee in the street fighting it out. It’s vital. When you’re very young, that’s what you go for, because it is what’s going to drag you wherever you’re going.

MS: It’s interesting that you emphasize the figurative aspect of narrative, especially in relation to punk and everyday experience, because your films often deal with the abstraction of power in politics. In some ways, they seem to suggest that political relationships are abstract enough, especially as they are lived by the figures on that landscape. Clean is a about very personal things happening to someone who is also caught up in the abstractions of globalization.

OA: Of course. My vision of politics is informed by Guy Debord. Ultimately, what Debord says is that the reality of oppression—of the power within modern society—is invisible and unformulated. It’s a way of understanding the world and not putting politics where movies usually put them. Like some kind of class struggle, which still exists to extremely brutal levels, of course. But the reality of the oppression is not there. That’s the visible side of it. The deeper truth of it is invisible and has nothing to do with everyday phenomena. The issue of politics—meaning politics in art—is a way of understanding the subtext of society. It’s about having real life characters having to deal with those invisible forces and being determined by them.

BP: One of the ways in which I see the politics of abstraction in your work is through the creation of a kind of global dérive, the way in which your characters drift seamlessly from country to country. They seem to enact a kind of psychogeography.

OA: Yes, yes, yes. It’s very interesting that you would say that because the one thing that has had the most influence on me, in terms of Situationist ideas, is very much the notion of the dérive—dérive within the city, dérive within the modern world. It has to do with the way we travel. We move from continent to continent, from city to city, and town to town. This poetic relationship to your surroundings and your trajectory in the modern world is a text that has its own meaning, including in the sense of Walter Benjamin—because it all goes back to that for me, to the Passages. In my last few films, I have been looking for some kind of modern version—some notion of a contemporary psychogeography. And I suppose that unconsciously this is what was happening when I was making my first film, Désordre [Disorder]. Basically, Désordre starts in the suburbs of Paris, moves to the center of Paris, then moves to London, then moves to New York.

BP: Along the same lines, the structures of your recent films always strike me as very complex responses to globalization. They neither wholly condemn nor celebrate it. There’s also an important sense of cosmopolitanism there, especially in terms of hospitality.

OA: As always, it has to do with the way you use words. One way you can use the word globalization is to say that the world has become unified. The world has become unified and that’s a good and a bad thing. It’s a bad thing in the sense that it is erasing cultural differences and it is creating populations that have to conform to codes that are alien to them. It destroys the very soul of some cultures. Ultimately, this culture is what Debord called the spectacle. It is a completely alienated, modern form that is taking over without anybody specifically wanting it. It is just happening. Everyone is staring helplessly and just watching it happen, figuring it is happening to others, or something. It is the primitive discourse of the commodity, ultimately—when the whole world becomes hostage to the circulation of commodities. And as always, it is visible in tiny things. When you are traveling and you go to some place in the world, you get to an airport, and from the airport you take a cab, and that taxi takes you to a hotel and at your hotel you sit in your room and turn on the TV. Someone then comes and picks you up, because you have an appointment with someone in an office somewhere. You’ve been there two days and you never see anything remotely connected to what the country is about, what the country has been about. You have been traveling but you stay in just one place. But the reality is that most of the reality there is gone. Whatever was real there has been neutralized. Whatever is happening is what has been happening on your drive from the airport to the hotel. It’s not that you’ve been missing reality. You’ve been at the core of reality and it’s horrible. That’s one side of it.

The other side of it is that it’s easier; there is more opportunity for travel, more opportunity for dialogue between cultures and between individuals. It’s faster. You write books, you make movies, and it all travels at the speed of light. If you want to write something you can just put it on the internet and it’s instantly there and all over the place. All of that is exciting. All that is interesting. And also the communication between all of that is a subject in itself that few artists deal with. One of the reasons I have been dealing with that is because is no one else has. There are many great filmmakers in France, but they are just not interested in that. One of the reasons that I have been making international movies is because I think that I have found a space in

terms of narration and what the world is today. The globalization of communication is interesting as long as there is not just a uniformity of individuals.

MS: I’m curious: In the context of this discussion of globalization, and also your discussion of the libertarian strains of May ’68 and its contradictions, how do you see the political situation in France today, where the gradual rise of liberalism in general has also meant the rise of globalization?

OA: To me, the main issue is the clumsiness of radical thought in France today. It’s lost all connection to the modern world. France is stuck on old ideas and has a very poor notion of geopolitics. So, you have this absolutely depressing landscape of some kind of modernist liberalism (in French liberalisme is more akin to neo-conservatism and free trade economics) that appropriates anything that is modern. And you have a completely decomposed left or leftism, completely glued to old values, old notions, old issues. Let me give you an example. I could not believe my eyes when I was going through Cahiers du cinéma recently. And there is this piece about this interesting movie, The Lives of Others. The problem they [Cahiers du cinéma] have is that the film is anti-Communist. It is dealing with the Stasi, which is a post-Gestapo system. Yeah, sure, it’s kind of anticommunism— depending on how you use the word—where you put the notion of communism! The depressing thing is that the radical movement in France is incredibly conservative. I can’t even answer your question. It’s just so sad. Anything that was modern in French political thought is gone. It’s gone. You have people who are influenced by Pierre Bourdieu. Pierre Bourdieu was a very interesting sociologist, but in terms of politics it’s extremely limited. Baudrillard was interesting also, even if I think that ultimately he was just a caricature of Debord. And then I am trying to think of anyone else who would have any kind of influence that would be meaningful, and I can’t think of a name.

BP: What about Badiou? He’s had an enormous influence on political thought, at least in the States.

OA: I suppose that he’ s more visible in the states than here.

MS: Maybe so [laughs].

OA: Here, I would not say that he has had any serious influence. Certainly not on me! [laughs]

BP: It seems to me that one of the things we might say about contemporary French philosophy is that politics and philosophy have become separated and also that art, philosophy, and politics have moved away from one another.

OA: Yes, yes, yes, of course. Which is a disaster! They have not moved apart, though. People think that they have, but they never do. It’s always politics, art, and philosophy together. If you think that they are separated, it is just bad philosophy, bad art, and bad politics. Ultimately, they are always one thing. Now, you have this movement to reform France. If the issue is whether or not to have shops open on Sundays and being able to buy fruit juices and yogurt at eleven o’clock in the evening, I’m all for it! It’s unbearable. It has to do with tiny things. But France’s industries have modernized—it’s happened, so I don’t think anything very important will come out of it. The problem is that the French reactionary right wing in power now has free reign because there is nothing in front of them. The socialists are only concerned with being one with the trade unions. The trade unions are about keeping an archaic wage system and benefits for this or that lobby group. It’s boring politics. I can’t say I feel concerned or involved, even if I can understand them. The basic difference between left and right in France, ultimately, is if people are concerned with helping the most disadvantaged part of the population, which should be the goal, basically, of any decent government. But we’re not talking about politics in the broader sense. We’re not talking about politics in the sense of how class systems work. Ecological issues should be the number one concern of any government, and yet is not within the scope of French politics—or only in a very minor way. You end up with a ridiculous situation, when Nicholas Sarkozy, for the first time, creates a major ministry of the environment—which is an idea that the Socialists did not even push.