“We always had the intention of rectifying it, to take that nice word from The Shining, when the butler’s trying to encourage Jack Nicholson to kill his family – to rectify the situation”

— Jake Chapman, about ‘Insult to Injury’

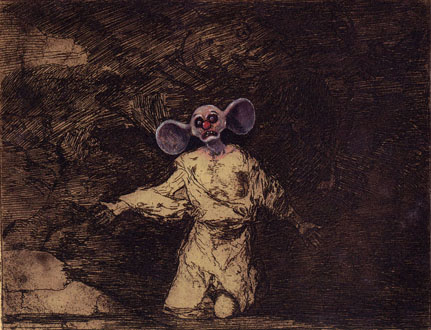

Some time ago, I bought Jake & Dinos Chapman’s ‘Insult To Injury’ publication, consisting of an endlessly fascinating series of manipulated/erased images. It started in 2001, when the Chapmans were able to purchase one of the few remaining sets of Goya’s ‘Los Desastres de la Guerra’ (‘Disasters of War’) prints. This group of 80 drawings was made between 1810 and 1820 as an attack on the horrors of war and its supposed romance and idealism, and has since become emblematic of art’s moral voice, as well as a powerful template for the representation of the insanity of such conflict (Picasso and Dali were both influenced by Goya’s work). The Chapmans meticulously “rectified” their Goya prints, drawing on top of what must be the most revered set of prints in existence. The artists superimposed cartoon faces, either those of clowns or puppies, onto figures Goya had intended as allegories of human suffering.

Dinos Chapman has explained: “We modified the Desastres in light of current events. Now they work better, if that doesn’t sound too immodest. The victims are de-individualized. Our ‘Desastres’ denounce any idea of rational humanity in the ideology of the powerful as pathetic and laughable.” “Goya was the first artist to make the scandal of war visible,” added Jake Chapman. “For us, it was about how, and if, moral positions should be or even can be made visible. The Desastres show the impossibility of distancing oneself morally from war. There’s no discerning the difference between good and evil anymore.”

Some interesting comments, by Christopher Turner:

“In ‘Regarding the Pain of Others’, Susan Sontag wrote that, unlike most images of mutilation and torture, Goya’s ‘The Disasters of War’ “cannot be looked at in a spirit of prurience” – it is devoid of pornography. The Chapmans would disagree. “I don’t think that there’s an opposition between a salacious interest and a noble one,” Jake Chapman says. For them there is a “convulsive beauty” in the violent image, and they are wedded to the Surrealists’ avant-garde belief that such shocks and jolts can wake us from the dream-state of a commodity culture by, as Jake puts it, “shocking the viewer from the edifice of comfort”. (The brothers’ work might be collectively titled ‘The Disasters of Capitalism’.) “He’s defended as a humanist,” Jake once said of Goya’s prints, “but there are moments of pleasure. They have an intensity, a humour and a tendency to undermine their own dignity.”

Jonathan Jones has written:

“Given how important the ‘Disasters of War’ were to Picasso, Dali and the image of the civil war, this is clearly an important, evocative, emotionally raw thing, and they have scribbled all over it. Yet the antecedent they themselves claim puts the gesture in a different light. In the 1950s, points out Jake, the American artist Robert Rauschenberg erased a drawing by Willem de Kooning, the great abstract expressionist painter. On the face of it, Rauschenberg was being aggressive – as a younger artist, a founder of pop and conceptual art, he was erasing the work of the older, dominant generation in a flamboyantly oedipal gesture. Yet he said he chose De Kooning for this fate specifically because he admired him; and he sought the older artist’s permission. Destruction can be an act of love. (…) Violet and white bursts of colour, the clown heads and puppy faces are astonishingly horrible. They are given life, personality, by some very acute drawing, and so it’s not a collision but a collaboration, an assimilation, as they really do seem to belong in the pictures – one art historical antecedent is Max Ernst’s collages in which 19th-century lithographs are reorganised into a convincing dream world. What the Chapmans have released is something nasty, psychotic and value-free; not so much a travesty of Goya as an extension of his despair. What they share with him is the most primitive and archaic and Catholic pessimism of his art – the sense not just of irrationality but something more tangible and diabolic.”

Rod Mengham

“If it is accurate to describe the relationship between the Chapmans and Goya as one of collaboration it is precisely because Goya’s graphic works exist in a perpetual process of sign transformation, of which ‘Insult to Injury’ is only the most recent evidence. In fact, ‘Goya’ itself (the holding concept used to organise a corpus of work, as much as a historical figure) is also a sign in constant flux. It has recently been argued that it is precisely art history’s redemption of Goya as the original humanist (where ‘Disasters of War’ represents the triumph of moral outrage over technical sophistication) that made a re-evaluation of the Goya’s ‘irrational supplement’, the indigestible aspect of his work, inevitable. In the face of this same logic, Bataille linked Goya with the Marquis de Sade, suggesting that they share a response to horror that ‘takes the form of a sudden leap into humour, and means nothing but just this leap into humour.‘ It is this Goya: irrational, expendable and hilarious, with whom the Chapmans collaborate.”

(…)

“It is in the wide margin of difference between the carnivalesque and the postmodern body that the Chapmans screw around with our received methods of viewing and reading the topographies of consumption, forcing us to experiment with our buried juvenile selves in imagining the world before we were forced to inherit it”.