“No doubt there are more and less painful ways of getting lost… But at the very least they all lead one who has left behind the categories of what can be said about society… to the point where what comes back to us from what we say is that no one can see where we’re going.”

— Jacques Rancière

“I don’t know where I’m going, but I know that you can’t get there that way”

— Glauber Rocha recalling a Portuguese saying

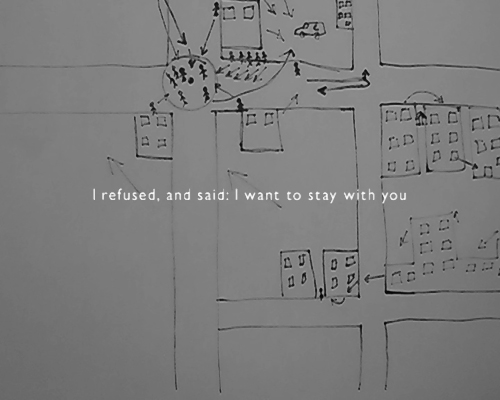

A tale of getting lost, letting go, setting forth without turning back. ‘A Child Kills himself’ feels like one of the most personal pieces Jacques Rancière has ever written. It does not only come across as a touching account of how his view on Roberto Rossellini’s Europa ‘51 has changed over time, but also of how his fundamental way of thinking has taken shape, much against the grain of the times. Indeed, when he describes the erratic wanderings of Irene, the character played by Ingrid Bergman, he might as well be referring to some of his own experiences. In Europa ’51, the complacent bourgeois lifestyle of Irene is violently overturned by the suicide of her young child. This traumatic event leads her astray through the outskirts of Rome, where she hopes to find some answers to the impassable questions which haunt her. This “voyage to the land of the people” is guided by her friend Andrea, who attempts to give meaning to Irene’s desperate search by situating it within the framework of Marxist thought: behind every individual agony, he suggests, we find an instance of a great social misery. What is hidden needs to be uncovered, what is unfamiliar needs to be explained, what is disordered needs to be cured. But there comes a time when the explanations given by others no longer suffice, when one needs to look elsewhere and see for oneself. That is how Irene’s progression towards (class) consciousness leads her ever further away from the trodden paths where things can supposedly be healed and revealed by the rules of knowledge, further down the shores of the river towards the barren wastelands where she starts nursing a tubercular prostitute, towards the cement factory where she takes the place of a worker and the steps of the church where she discovers a new faith. Instead of an act of “consciousness”, what takes place is a process of conversion. Irene’s own unplanned exploration turns out to be a deviation which displaces her from the system of explanations and motivations that determines what the proper rules of conduct and models of social behaviour are, the common sense that defines what is “sensible”. In letting go of all chains of causes and effects, knowledge and truth, she becomes a stranger who no longer has a valid place in the layout of paths and traces that others make up to be “reality”; a foreigner out of place and out of reason, lost in the void of uncertainty, in the niente, the nothingness that silently lingers throughout the film.

Rancière readily admits that when he first viewed the film during the 1960s, his Marxist-inspired critical expectations were frustrated by Irene’s retreat into religious idealism, which seemed to contradict the first, “realist” half of the film. This part presented itself as a perfect marriage between Marx’ historical materialism that provided the theoretical foundation of the workers’ struggle and the materialism of the relation between bodies and spaces that defines the mise-en-scène. But as the main character ventures from the world of labor and oppression to the spiritual path towards sainthood, the materialist connection is radically severed. In order to reconcile the two seemingly opposing views, “it then became necessary to say”, writes Rancière, “that the materialism of the mise- en-scène had been diverted by the personal ideology of the director.” In the same way as Marx once praised Balzac, the reactionary realist, for unwillingly revealing the truth of the capitalist world, Rancière argued that Rossellini, the Catholic idealist, showed something other than what he intended: in her inability to achieve an understanding of the social formations in which she found herself caught, Irene did not find salvation, but utter “madness”. Still not content with this interpretation, it took Rancière twenty-five years years to change his view on the film: more than two decades of digging in the archives of proletarian dreams and aesthetic experiences, where he took flight from the Althusserian science of the hidden that he had denounced so fiercely after the events of 1968. “For one who had been invited to look behind things, the break comes from looking to the side instead,” he writes. With that in mind, Irene’s conversion no longer indicates a lack of ”consciousness”, but a departing from it: it does not stem from a revelation, but from an alteration that leads her towards places where she is not supposed to be, where all certainties are put into question. A world without coordinates where nothing is identifiable as such any longer. “Irene bids farewell to this consciousness in the Socratic manner: she lets it go.” This is the Socratic atopia that characterizes Irene’s wanderings: a being out of place that originates in an act of trust. Trust in what we see, in what lays before us and the uncertain paths that we may have to walk.

It is an idea that runs through all of Rancière’s work, ever since he parted from Louis Althusser, his former teacher: the denunciation of all narratives of historical necessity and teleologies of “coming-to-consciousness”, which are always based on a certain distribution of sense: there are some who need to speak for others who know not what they do, because they know not how to see. Such is the position of Andrea, Irene’s well-intentioned guide: he is there to point out what is to be revealed, to make knowledge out of what others do not know. It is a position of basic mistrust, inherent in the Marxist critical tradition: truth can only be found behind appearances. But in the process of uncovering, the truth only gets reduced to the certainty of place, the only “right” place, the place of knowing. According to Rancière however, “the problem is not that of knowing what one does… The problem is to think about what one does, to remember oneself… ” Remembering oneself by becoming foreigner, by refusing the dominant interpretative schemas that connect sense with sense: this is the fundamental idea which underlies Rancière’s thinking. The challenge is not one of unveiling, he suggests, but of “encircling”. That is what Irene’s gaze does: an indeterminable encircling that unlocks the settled system of places excluding all forms of atopia, that undoes the certainty of social identities by exceeding everything that they are supposed to be one with. It is a matter of establishing a logic of “heterology”: one that denies given identities that pin down people to certain names, relations, times and places; one that disturbs the fabric of the sensible sustained by the dominant network of meanings, one that unsettles and undermines the system of coordinates that determines where and what we are supposed to be. It is the foreigner’s gaze that puts us in touch with the world, not the view of those who decide to stay on safe grounds, who stop looking, who cease to put their trust in what they see and sense. Irene, like Rancière, knows what to respond to all those who claim to be in the know, all those who designate what is meaningful and worthwhile and what isn’t: there is something else to be done, something that is not determined, and will perhaps never be. Something that defies the reasoning behind the choices we all have to make at one time or another, we who are painfully torn between fragile sensitivity and common sensibility, mindless longing and mindful sustaining, between knowing and unknowing, holding on and letting go.

(For B)