ACCELERATED LIVING

SCREENINGS

In the context of the programme “Accelerated Living”, part of IMPAKT FESTIVAL 2009, 14-18 October 2009, Utrecht, NL. Preview here.

All screenings @ Filmtheater ‘t Hoogt

It seems as if time is increasingly out of joint. We no longer experience time as a succession or an acceleration of events, but rather as being adrift in a fragmented world of information stimuli, out of the realm of chronology and linearity. What is the impact of this evolution on our perception patterns? How do the different internal, natural, social and technological rhythms relate to each other and influence our daily sensory perception? What is the role and potential of cinema, together with music, the art form most particularly devoted to the shaping force of time? These and other questions will be explored through a series of contemporary and historic film and video works addressing the relation between space, movement, technology and (our experience of) time.

———————————————————————————————————————————————————

As Time Goes By

Friday 16 October, 13:00 Film Theater ’t Hoogt, Hall 1

There is in the world a great and yet ordinary secret. All of us are part of it, everyone is aware of it, but very few ever think of it. Most of us just accept it and never wonder over it. This secret is time.

— Michael Ende

In his book The Psychology of Time French psychologist Paul Fraisse claims that we are only aware of time when it appears distorted. We have no experience of time as such, according to Fraisse, only of specific sequences and rhythms. It is not time itself but what goes on in time that produces temporal effects. In this sense, Cinema – the sculpting of time – is the medium best fit to penetrate its mysteries. The films and videos in this programme use the plasticity of the moving image and the inherent dialectics between the continuous and the instantaneous in order to explore the tensions between the time of watching, the image’s own time and the existential dimension of time.

Morten Skallerud, A Year Along the Abandoned Road

Norway 1991, 35mm, 12:00 min

A portrait of a deserted fishing village in Northern Norway and a journey through time and space: the four seasons unfold in a continuous camera movement through the village of Børfjord. This 12 minute short film was filmed in 70mm Super Panavision, using a specially developed “nature animation” technique. The result is a magic flight in one single shot, along the remains of a village road. At the same time a whole year passes by at 50.000 times normal speed!

Kurt Kren, 31/75 Asyl

Austria 1975, 16mm, 9:00 min, mute

Recorded over the space of 21 days by selectively masking and exposing the same three rolls of film, the transformations of a landscape are simultaneously recorded in a static image. Peter Weibel coins this methodology “temporally extended multiple lighting”. “Since the weather was changing throughout the time of shooting (March/April) the brightness of the picture is very different from take to take. Sometimes snow is seen on the ground… The exchange of the masks does create movement, but not as a course of time towards a goal.” (Birgit Hein)

Gary Beydler, Venice Pier

United States 1976, 16mm, 16:00 min

“I wanted to make a film that was exactly one year in the making. I love the ocean, and I decided to shoot on the Venice Pier, which was about a quarter mile long. About every ten feet, there are divisions in the pier, which I decided to use as the shooting points. I started shooting maybe in November or December, and shot it all the way through to the following year, finishing on the same date. Watching the film, you’re moving forward every so slowly, through different times, different seasons, different situations. Sometimes you get the feeling of movement, sometimes you don’t. No need for staging, I just shot things that were happening.” (GB)

Rose Lowder, Bouquets 1-10

France 1994-95, 16mm, 11:00, mute

Bouquets 1-10 is Lowder’s first collection in an ongoing series of one minute episodes, each composed of footage shot around a general geographic location that has been alternately woven, frame by frame, into a single film reel and connected through the interstitial still life image of a flower that cues the beginning of each integrated film Bouquet. Each bouquet of flowers is also a bouquet of frames mingling the plants to be found in a given place with the activities that happen to be there at the time. Lowder uses the film strip as a canvas with the freedom to film frames on any part of the strip in any order, running the film through the camera as many times as needed.

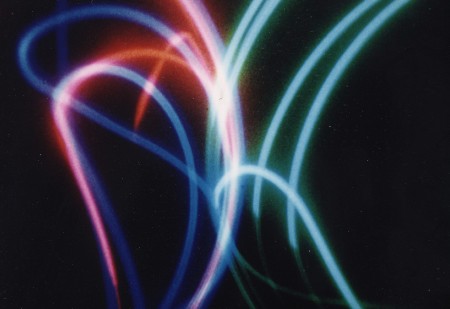

Joost Rekveld, #3

Netherlands 1994, 16mm, 4:00 min, mute

“#3 is a film with pure light, in which the images were created by recording the movements of a tiny light-source with extremely long exposures, so that it draws traces on the emulsion. The light is part of a simple mechanical system that exhibits chaotic behaviour. The film was made according to an extensive score covering colour, exposure, camera position, width of the light-trail and the direction and speed of movement of the mechanical system. The light that draws the traces was fastened to a double pendulum. This system is known from chaos-theory and shows unpredictable behaviour in a certain range of speeds.” (JR)

William Raban, Broadwalk

United Kingdom 1972, 16mm, 4:00 min

“Originally, this was a four-minute time-lapse film which was shot continuously over a twenty-four hour period. The camera was positioned on a busy pathway in Regent’s Park, and recorded three frames a minute. The shutter was held open for the twenty-second duration between exposures, so that on projection, individual frames merge together making the patterned flows of human movement clearly perceptible. The time-lapse original was then expanded by various processes of refilming to reveal the frame-by-frame structure of the original.” (WR)

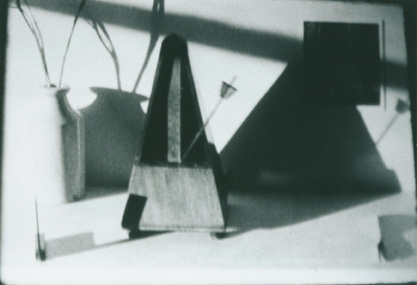

Guy Sherwin, Clock & Candle, Metronome, Barn Door (from the Short Film Series)

United Kingdom 1975-1998, 16 mm, 9:00 min, mute

It is quite impossible to offer a definitive description of Guy Sherwin’s Short Film Series, since it has no beginning, middle or end. Composed of a series of three minute (100ft.) sections which can be projected in any order, the series is open-ended and ongoing. The ideas of film as a record of life and the camera apparatus as a ‘clock’ which actually marks ‘time’ are present throughout the series. Many parts deal with two rates of time measurement, as in Clock and Candle, or construct visual paradoxes, as in the shuddering stasis of Metronome – an illusion caused by the clash between the spring-wound mechanisms of the Bolex camera and of the metronome itself. In Barn Door the semi-strobe effect of light pulsations flattens the distant landscape.

Michael Snow, See You Later / Au Revoir

Canada 1990, 16mm, 18:00 min

A simple plot: Michael Snow as a “Walking Man”, leaving his office in extreme slow motion. In a single panning shot thirty seconds of real-time action are distended to eighteen minutes by means of a high speed video camera then step printing the video onto film. Filming on video saturates the color, bringing a luxuriant richness to the work, which retains the simple conception of Snow’s earlier films and once again highlights cinematic duration. With See You Later Snow continues his exploration of the ways in which technology enhances our ability to perceive, live in and experience the world.

———————————————————————————————————————————————————

Chronoschisms

Friday 16 October, 15:00, Film Theater ‘T Hoogt, Hall 1

’The movie projector’s a kind of clock’, Ed Bachelor said. Somewhere inside the machine beats a Piranesi space, shaped and given dimension by a string of exposures of a seated woman undulating gravity-free. Who is the alluring lady of this filmstrip tease? I call her Dinah, because the name contains a D, an N, and an A.

— Ken Jacobs

Modern cinema is a reflection of the rationalization and standardisation of time. The amazement caused more than a century ago by the possibility of recording and analyzing movement has given way to an obsession with imitating “real time”. The certainties of progress and predictability, the two pillars of capitalist modernity, have also shaped the construction of cinematographic time. This programme features a selection of works that subvert the mimetic function of audiovisual media, and intervene – via mechanisms of variation and repetition – in the epistemological process of fragmentation that constitutes the basis of the conventional cinematographic vision.

Fred Worden, Throbs

United States 1972, 16mm, 7:00 min

Found footage of circuses, fairgrounds and car crashes is repeated, distorted and layered, brought to the point of destruction and then back again, recoalescing to a hypnotic, looping and crescendoing soundtrack. Frequently employing an optical printer for his projects, Worden’s investigations involve subtle explorations of light, texture, colour, exposure, detail, and the other physical qualities of celluloid, emulsion, and the light that must pass through it. In Throbs unusually beautiful clashes of colour and shape occur a result of Worden’s creative manipulation of time and use of superimpositions.

Malcolm Le Grice, Berlin Horse

United Kingdom 1970, 16mm, 9:00 min

“This film is largely filmed with an exploration of the film medium in certain aspects. It is also concerned with making certain conceptions about time in a more illusory way than I have been inclined to explore in many other of my films. It attempts to deal with some of the paradoxes of the relationships of the “real” time which exists when the film was being shot, with the “real” time which exists when the film is being screened, and how this can be modulated by technical manipulation of the images and sequences. The film is in two parts joined by a central superimposition of the material from both parts.” (MLG) The soundtrack was supplied by Brian Eno who at the time was exploring, in sound, a similar use of loops that changed their phase shift.

Chris Garrat, Versailles

United Kingdom 1976, 16mm, 11:00 min

”For this film I made a contact printing box, with a printing area 16mm x 185mm which enabled the printing of 24 frames of picture plus optical sound area at one time. The first part is a composition using 7 x 1-second shots of the statues of Versailles, Palace of 1000 Beauties, with accompanying soundtrack, woven according to a pre-determined sequence. Because sound and picture were printed simultaneously, the minute inconsistencies in exposure times resulted in rhythmic fluctuations of picture density and levels of sound. Two of these shots comprise the second part of the film which is framed by abstract imagery printed across the entire width of the film surface: the visible image is also the sound image.” (CG)

Iván Zulueta, Frank Stein

Spain 1972, 16mm, 3:00 min

Filmed before Arrebato, Zulueta’s Frank Stein is a very personal reading of horror cult classic Frankenstein (James Whale, 1931), filmed directly from its television broadcast and reducing Whale’s original to only three packed and dizzying minutes, during which the intimate monster evolves at an unusual rate. A game of rhythm and tempo which Zulueta will continue to explore in a series of super 8 short films such as King Kong, Mi ego está en babia, A malgam A and El mensaje es facial.

Joyce Wieland, Handtinting

Canada 1967-68, 16mm, 6:00 min, mute

“This film is composed of cut-away shots that Wieland filmed for a proposed documentary on a West Virginia job training center. Wieland dyed this leftover footage, added flashes of other footage, and scratched and perforated the film itself with her sewing needles. Recent allusions to Handtinting incorporate into feminist critical discussion the importance of tools and methods of working particular to women’s crafts. The movie is comprised of looped and reversed images of the girls dancing, swimming, and talking so that a repetitive or loop effect results in actions that recur but are never completed. Their incomplete movements and gestures become isolated rhythms of social rituals. Lacking spatial depth and temporal completion, the repetitive actions negate the illusion of solid space in documentary cinema.” (Lauren Rabinovitz)

Bruce Conner, Marilyn Times Five

United States 1972, 16mm, 10:00 min

Out of fifty feet of footage from a girlie 1950s movie (Apple Knockers and the Coke, featuring Arline Hunter, an actress who clearly attempts to impersonate Monroe), Conner has conjured an allegory of the human cycle of birth and death. He breaks up the tenuous continuity of the original production by reordering poses and distending certain movements via looped repetition or a form of progressive looping in which one movement begins in one shot, is incrementally advanced in the next shot, and so on. Five individual sequences are build around a lush recording of ‘I’m through with Love’; each successive permutation displays pieces of previously unseen footage interrupted by passages of black leader. Conner’s intent, in his own words, “was to take some parts of the found footage and rearrange them to see if the quintessential ‘Marilyn’ could emerge”.

Ivan Ladislav Galeta, Water Pulu 1869 1896

Croatia (SFRY) 1987-88, 16mm, 9:00 min

In Water Pulu we see a game of water polo. The cameras keep the ball in the middle of the picture (an effect achieved by multiple exposure, copying and manipulations on the optical bench). It becomes the sun around which the human activities revolve. The first movement from Debussy’s La Mer and the noise of the game, which is mixed with the song of the dolphins, refer to water as the essential element for life. An ingenious system of number symbolism governing the order of images and cuts, and references to the significance of sun and water in culture and art place this film in the context of timeless human self-reflection. “Galeta hides a true chamber of wonders behind the clear, mathematically abstract structure of his films and videos, meticulously compiled rhythmically frame for frame, each work likewise presenting an analysis of the film medium.” (Georg Schöllhammer).

Ken Jacobs, What Happened On 23rd Street In 1901

United States 2009, video, 13:00 min, mute

“It was a set-up. A couple walks towards the camera, a sidewalk air-vent pushes the woman’s dress up. Layers of cloth billow and she is mortified. The moving picture camera, already in place and grinding away, captures the event and her consternation becomes history, now transferred to digital and shown everywhere. In this cine-reassessment, the action is simultaneously both speeded up and slowed down. How can that be? Overall progression is prolonged, so that a minute of recorded life-action takes ten minutes now to pass onscreen. Slow-motion, yes? No. Instead, the street action meets with a need to see more, and there descends upon the event a sudden storm of investigative technique in the form of rapid churning of film frames, looping of the tiny time-intervals that make up events. Black intervals enter and Eternalisms come into play meaning that directional movements continue in their directions without moving, potentially forever.” (KJ)

Rafael Montañez Ortiz, Dance n° 22

United States 1993, video, 10:00 min

“In my video work, I seek to suspend time, to magnify beyond all proportion the fantasy, dream, or nightmare I glimpse in even the most realistic straightforward documentary footage, in even the most innocent storyline.” (RMO). In this video Montañez Ortiz rechoreographs a scene from the Marx Brothers’ A Night at the Opera by stuttered editing. The original, as we know it, is a love of anarchy. What Montañez Ortiz achieves here is sheer madness; the walls literally vibrate. “In an ongoing dance series, [Ortiz] has used this [editing] technique to explore the rhythmic undertones in social interactions, often fights among men. Ortiz describes the overall effect as a “holographic” space within the Hollywood text, yet outside the familiar perceptual mode and linear structure of mass media.” (Chon Noriega)

Norbert Pfaffenbichler, Mosaik Mécanique

Austria 2007, 35mm, 9:30 min

The third part of Pfaffenbichler’s ‘Notes on Film’ series, which borrows its title from a combination of Fernand Leger’s Ballet Mécanique and Peter Kubelka’s Mosaik in Vertrauen. All the shots of the slapstick comedy A Film Johnnie (USA, 1914) are shown simultaneously in a symmetrical grid, one after the other. Each scene, from one cut to the next, from the first to the last frame, is looped. Spatialisation takes the place of temporality, synchronism that of chronology. A polyrhythmic kaleidoscope is produced as a result (reflected in Bernhard Lang’s music), tearing the audience back and forth between an analytic way of seeing rhythmic patterns and the impulse to (re)construct a plot.

———————————————————————————————————————————————————

Place Over Time

Friday 16 October, 17:00, Film Theater ‘t Hoogt, Hall 1

Take some time, take some more, time is passing, the time of your life, the earth rotates, seasons come and go, the machine sorts zeros from ones, as another thousand tiny bursts of phosphorescent light dance to the rhythm of the wind and the tide.

— Chris Welsby

This programme brings together a number of works focusing on landscapes, as meditative time capsules in which different events unfold, activating the potential pasts of a place. Whereas the landscapes of narrative cinema are often latent expressionistic theatres, echoing the minds of the human figures within them, these films fully focus the attention on the rhythms of the natural world, from the microscopic to the cosmological. The only signs of human life are the traces of destruction left behind by our urge to move faster across time and space. Virilio argues: “it is no longer God the Father who dies, but the Earth, the Mother of living creatures since the dawn of time. With light and the speed of light, it is the whole of matter that is exterminated”.

Emily Richardson, Cobra Mist

United Kingdom 2008, 35mm, 7:00 min

Cobra Mist explores the relationship between the landscape of Orford Ness in Suffolk and the traces of its unusual military history, particularly the experiments in radar and the extraordinary architecture of the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment. The place has a sinister atmosphere, which the architecture itself begins to reveal and the sense of foreboding is accentuated via the film’s soundtrack by Benedict Drew. “The film cuts between stillness and activity through time-lapse, a sweeping camera and changing light. The sound also cuts between birdsong and industrial noises suggesting activity when onscreen there is non.” (William Fowler).

Chris Welsby, Sky Light

United Kingdom 1988, 16mm, 26:00 min

Sky Light is a single screen version of the 6-projector installation with the same title. “An idyllic river through a forest, flashes of light and colour threaten to erase the image, bursts of short wave and static invade the tranquillity of the natural sound. The camera searches amongst the craggy rocks and ruined buildings of a bleak and windswept snowscape, a Geiger counter chatters ominously in the background. The sky is overcast at first but gradually clears to reveal a sky of unnatural cobalt blue. This film was made in response to some very strong feelings experienced at the time of the Chernobyl disaster in 1986.” (CW)

Jeanne Liotta, Observando el Cielo

United States 2007, 16mm, 19:00 min

“Seven years of celestial field recordings gathered from the chaos of the cosmos and inscribed onto 16mm film from various locations upon this turning tripod Earth. This work is neither a metaphor nor a symbol, but is feeling towards a fact in the midst of perception, which time flows through. Natural VLF radio recordings of the magnetosphere in action allow the universe to speak for itself. The Sublime is Now. Amor Fati!”. (JL) Soundtrack by Peggy Ahwesh, with recordings by Ahwesh, Liotta, Mailie Colbert, Barbara Ess and Radio Guitar.

Peter Hutton, Time and Tide

United States 2000, 16mm, 35:00, mute

The first section of the film is a reprint of a reel shot by Billy Bitzer in 1903 titled Down the Hudson for Biograph. It chronicles in single frame time lapse a section of the river between Newburgh and Yonkers. The second section of the film was shot by filmmaker Peter Hutton and records fragments of several trips up and down the Hudson River between Bayonne (NJ and Albany (NY). The filmmaker was travelling on the tugboat “Gotham” as it pushed (up river) and pulled (down river) the Noel Cutler, a barge filled with 35,000 barrels of unleaded gasoline. “Combining the luminescence and formal contemplation of the Hudson Valley painters with documentary and ecological concerns, Time and Tide extends the panoramic field of Hutton’s previous Portrait of a River. And after decades of an exclusive devotion to and mastery of reversal black and white stocks, Time and Tide marks Hutton’s inaugural foray into color negative.” (Mark McElhatten)

———————————————————————————————————————————————————

Terminal Velocity

Friday 16 October, 21:00, Film Theater ’t Hoogt, Hall 2

With the fantastic illustration of the dromosphere of the speed of light in a vacuum, we are at least to question the witnesses, those of Chernobyl, for instance, for in 1986 the time of the accident suddenly became for them, and finally for all of us, the ‘accident in time’.

— Paul Virilio

Chernobyl has irremediably infected our perception of time. A few seconds: that’s all it took to lose control of the reactor. There wasn’t any more time for those who were exposed to a fatal dose of radioactivity. The explosion was only visible for a moment, but seemed to last for an eternity. In only a few days the radioactive cloud flew all over the world, infecting a great number of people. But it will take several millennia until the released radioactive isotopes are completely neutralised. This selection considers the rise of the nuclear threat after 1945 and the application of the technological principles of mass production to mass destruction.

Leslie Thornton, Let Me Count the Ways : Minus 10, 9, 8, 7

United States 2004, video, 22:00 min

Let Me Count the Ways is a series of meditations on violence and fear, and their reverberations on cultural history. The episodes have been built out of a mixture of personal reflections and diverse image material which present the phenomenology of fear with an intensity that breaks abruptly the border between past and present. Just as in earlier work, Thornton explores the social effects of new technologies and media, but here she goes deeper into autobiographical territory, suggesting we are all involved in these developments. “I want to spark the imagination into sensing something of a past, while at the same time giving a place for the images to have a full, awesome present. Not to privilege the past, but to experience wonder that it exists, like looking at stars.”(LT)

Pavel Medvedev, On the Third Planet from the Sun

Russia 2006, 35mm, 32:00 min

A portrait of life in the Arkhangelsk area near the Arctic Circle in Northern Russia, where the Soviet army carried out tests of the hydrogen bomb in 1961. The local Pomors still live the way they have for centuries; preoccupied with fishing, hunting and growing plants. But the nearby rocket launching site has brought with it a new type of hunt, the hunt for “space garbage” which they sell as scrap iron or to use in housekeeping and farming. Medvedev delivers a striking visual exploration of environmental destruction and the rebirth of a community.

Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, Atomic Park

France 2003, 35mm, 8:00 min

Shot on location at White Sands, New Mexico, very near Trinity Site – the location of the first atomic explosion in July 1945 – Atomic Park captures sunbathers and tourists taking in the striking sun: the place is now home to a recreation area as well as a military base for research. The film presents a national park, a white desert, a natural exhibition space where each presence, each movement can give way to different interpretations and to a new reading of the setting. On the soundtrack we hear faintly the voice of Marilyn Monroe in her desperate and accusatory monologue about manly violence in The Misfits (1961). Partially obscured by a degree of over-exposure, Atomic Park evokes the contradictory experiences of leisure and danger.

Bruce Conner, Crossroads

United States 1976, 35mm, 36:00 min

“From material recently declassified by the Defense Department, Conner has constructed a 36-minute work, editing together 27 different takes of the early atomic explosions at Bikini, all un-altered found footage in its original black and white. The film is without dialogue or descriptive factual detail. It consists simply of the visual record of these first bombs’ destructive capability. In his researching, Conner uncovered a vivid historical account of the Bikini tests written for the Joint Task Force (Army and Navy) by W. A. Shurcliff. Interestingly, what one would expect to be a dry, methodical description is in fact dramatic and fascinating, revealing how impossible it was to suppress the bomb’s overwhelming power. This original state of consciousness is what Conner wants us to re-experience in his film. What were the circumstances surrounding these tests, as described by Shurcliff?” (William Moritz & Beverly O’Neill, 1978). Music by Patrick Gleeson and Terry Riley.

———————————————————————————————————————————————————

Rush Hour

Saturday 17 October, 13:00, Film Theater ‘t Hoogt, Hall 1

I love my syncopated city. This is my fascinating rhythm

I need my syncopated city. I love my sense of dislocation

— London Elektricity

The city is the place where the forces and fruits of modernity meet: capitalist enterprise, mechanised industrialisation, the movement of anonymous crowds and fast vehicles, kaleidoscopic shopping windows for all tastes and colours. “A city made for speed is made for success” wrote Le Corbusier in 1920. This influential architect saw in speed and urban planning the keys to better living conditions, but failed to take into account the fundamental ambiguities of modern urban living: the simultaneous feeling of agitation and stress, opportunism and nonchalance, order and chaos. This contradiction appears to be the city’s essence. This is the central idea behind this screenings programme, in which urban surroundings are observed, dissected and transformed into matrices of energy and rhythm, surfaces and patterns, colour and design.

D.A. Pennebaker, Daybreak Express

United States 1958, 35mm, 6:00 min

“A short film for those with a short attention span”. A five-minute portrait of the soon-to-be-demolished Third Avenue elevated subway in New York City set to Duke Ellington’s music. A simple composition of city images in 1950s, the directorial debut of D.A. Pennebaker – one of the fathers of American “direct cinema” – is an extraordinary experiment in using the camera in travelling motion. “I wanted to make a film about this filthy, noisy train and its packed-in passengers that would look beautiful, like the New York City paintings of John Sloan, and I wanted it to go with one of my Duke Ellington records, ‘Daybreak Express’.” (DAP)

Marie Menken, Go! Go! Go!

United States 1964, 16mm, 12:00 min, mute

“Taken from a moving vehicle, for much of the footage. The rest uses stationary frame, stop-motion. In the harbor sequence, I had to wait for the right amount of activity, to show effectively the boats darting about; some sequences took over an hour to shoot, and last perhaps a minute on the screen. The “strength and health” sequence was shot at a body beautiful convention. Various parts of the city of New York, the busy man’s engrossment in his busy-ness, make up the major part of the film … a tour-de-force on man’s activities (…) My major film, showing the restlessness of human nature and what it is striving for, plus the ridiculousness of its desires”. (MM)

Gordon Matta-Clark, City Slivers

United States 1976, 16mm, 14:00 min, mute

A formal investigation of New York’s urban architecture, it was planned to be projected on the exterior facade of a building. Employing mattes to segment the film frame into narrow vertical bands that readily accommodate the proportions of Manhattan’s high-rise skyline, Matta-Clark creates a dynamic city symphony. The visual slivers capture both the monumentality of the built environment and the hectic fragmented pace of urban life as traffic and pedestrians traverse intersections, workers enter and exit a revolving door, and diaristic texts appear running along the edges of the frame. “Time is fluid, again, as slivers of scenes overlap in rhapsodic simultaneity.” (Steve Jenkins)

Yo Ota, Incorrect Intermittence

Japan, 2000, 16mm, 6:00 min

“This film offers a metacinematic study of tempo and change and a figure of velocity. It consists of three interrelated parts or scenes that are unified by three different locations in Tokyo: a railway crossing, a shopping street, and a temple. In Ota’s experiment, editing is not the primary tool, yet it shows the emphasized rhythm of a montage film. To obtain this paradox of continuity, duration, change, and speed, Ota recorded each location at the interval of hours, and sometimes even days, by using different filters and by alternating the camera speed. The result mirrors aspects of both duration and speed while using real time as an editing tool. It represents an inquiry into the abstract space-time of cinema where Ota plays with the physical fact that time is a ‘function of movement in space’.” (Malin Wahlberg)

Nicolas Rey, Terminus For You

France, 1996, 16mm, 10:00 min

“Rey’s film uses a simple, classic trope of contemporary urban life: the moving walkway at the subway station becomes a dual symbol, an evocation of the human condition in the industrial world, as well as a metaphor for the workings of the most representative of the era’s art forms: the cinema. Like the film loop, the walkway circles endlessly, yet its visible portion, shadowing the human walk, offers an illusion of linear progression, transporting human bodies from A to B with the smooth lateral movement of a traveling shot, and the pre-determined direction and calculated time of an endlessly repeated scenario. (…) Urban life’s mechanical rhythms continue to provide an artificial sense of continuity, direction and purpose where fragmentation and senselessness reign.” (Martine Beugnet)

Jim Jennings, Public Domain

United States 2008, 16mm, 8:00 min, mute

In a career that spans over three decades, Jim Jennings’ lyrical sensibility has thoroughly captured the environs of New York from its bridges, trellises, and elevated subway lines to the closely observed nuances of fellow New Yorkers. “The film’s title was a response to the debate in New York over the City’s plan to require licensing and insurance from filmmakers to film on the street, in the public realm. Fortunately, the City backed down. In its whirling color, this film expresses my never-ending fascination with the street.” (Jim Jennings)

Dryden Goodwin, Hold

United Kingdom 1996, video, 5:00 min

People observed in the street are a frequent subject in Dryden Goodwin’s films, drawings and installations. His video Hold considers the nature of memory, exploring the tension between our desire to hold onto experiences against the inevitability of the passing of time. A recollection of all the people seen through a day, Hold exploits the fact that film is made up of separate frames; it features a new person on practically every frame, or every eighteenth of a second. Although occasionally two or three people are held longer, using consecutive frames to jump back and forth between them, the sound and the mechanism of the film are relentless, no resolution is reached, we continue to move forward.

Michel Pavlou, Interstices

Greece/Norway, 2009, video, 3:00 min

A series of scenes shot in the Paris metro, edited to the rhythm of the trains’ automatic doors. The kaleidoscopic effect of viewing through the windows of trains as they pass each other determines the geometry of the image. A composition of parallel and divergent vertical and horizontal movements: those of the camera but also of the trains and the scrolling publicity panels. Everyday traffic and urban rush are recurring themes in the work of Michel Pavlou, concerned with the investigation of film’s primary dimension: time. His films and videos move in the interstices of time and space, addressing the tensions between static and dynamic, present and absent, revelation and concealment.

Mark Lewis, Rush Hour, Morning and Evening, Cheapside

Canada 2005, 35mm to HD video, 4:00 min, mute

Shadows of pedestrians during morning and evening rush hour at a major urban intersection. Scenes of people scurrying to and fro, captured from a very different perspective: Only their shadows appear to collide randomly. Everyone is hurrying to work. And subsequently to their homes. Shot in London’s financial district, Rush Hour, Morning and Evening, Cheapside is an attempt by Canadian filmmaker-artist Mark Lewis to capture the urban fabric.

———————————————————————————————————————————————————

Fast Lane

Saturday 17 October, 15:00, Film Theater ’t Hoogt, Hall 1

Speed is the form of ecstasy the technical revolution has bestowed on man. (…) When man delegates the faculty of speed to a machine: from then on, his own body is outside the process, and he gives over to a speed that is noncorporeal, nonmaterial, pure speed, speed itself, ecstasy speed. A curious alliance: the cold impersonality of technology with all the flames of ecstasy.

— Milan Kundera

Belgian speed racer Camille Jenatzy was the first man to break the 100 km/h barrier in 1899. The car he entered History with was called “La Jamais Contente”. Never satisfied: modernity in a nutshell. The insatiable hunger for machine speed, as the motor for progress, but also as a sensuous experience, is the central theme of this programme. The arrival of trains, cars, airplanes and space shuttles changed irrevocably the relationship between time and space. It increased the speed with which bodies could move across space and dramatically shortened the time involved. But this increase of speed brings along contradictions, paradoxes and dangers….

Guy Sherwin, Rallentando

United Kingdom 2000, 16mm, 9:00 min

Accelerating and decelerating rhythms taken from a train as it enters a station. Sound is adapted from Honneger’s orchestral work ‘Pacific 231’. Rallentando is part of Sherwin’s Train Films, which he will present during Impakt in the form of a film performance (see ‘Dopes to Infinity’). Inspired by the movements and parallax effects of objects appearing to cross each other when viewed from a moving train, as well as by the parallels between film form and train journeys, these films have titles which denote specific musical forms; Canon, Stretto, or instructions; Da Capo, Rallentando.

Gerard Holthuis, Hong Kong (HKG)

Netherlands 1999, 35mm, 13:00 min

The city of Hong Kong is often seen as a living example of the Virilian notion of ‘speed’. “Change takes place in present-day Hong Kong in ways that do not merely disturb our sense of time but completely upset and reverse it. (…) It suggest[s] a space traversed by different times and speeds”. (Ackbar Abbas). In 1998 Kai Tak airport in the middle of Hong Kong was closed. Approaching Kai Tak was a unique experience for the passengers . «One could read the newspapers in the street» one passenger exclaimed. In Hong Kong (HKG) Holthuis films the approach and the passing by of the airplanes in the middle of a city. An observation at the end of this century. Music by David Byrne.

Ilppo Pohjola, Routemaster: Theatre of the Motor

Finland, 2000, 35mm, 13:00 min

Routemaster – Theatre of the Motor is a filmic portrait of speed consisting of strobe-like, fast-flickering shots, and grainy, monochrome images of speeding rally cars. While Pohjola’s Asphalto was still concerned with human interactions, here the absence of humanity is total: what remains are the machines in movement that is an end in itself. The rhythmic structure is provided by slow-motion, close-up shots of checkered flags, repeated at regular, mathematical intervals, with passing shades of blue providing almost the only colour in the film. At times, the accelerating speed of the images makes it painful to watch the film, like a sort of visual Blitzkrieg waged on the human nervous system through the viewer’s tortured retinas.

Artavazd Pelechian, Mer dare / Our Century

Armenia (USSR) 1982, 35mm, 50:00 min

Pelechian’s Our Century is a masterful montage of archive footage of space travel, edited with images from the beginnings of manned flight. A meditation on the space race, the Soviets’ and Americans’ Icarus Dream, the deformed faces of astronauts undergoing acceleration, the imminent catastrophe…. Our century is the century of conquests and genocides, the century of vanity. The absurdity of Man’s totalitarian inclination to colonise and occupy worlds. A philosophical film-poem; Pelechian works his images as if they were a musical score. A symphony about humanity, nature and the cosmos.

———————————————————————————————————————————————————

Chaosmosis

Saturday 17 October, 17:00, Film Theater ‘t Hoogt, Hall 1

In every whirlwind hides a potential for form, just as in chaos there is a potential cosmos. Let me possess an infinite number of unrealized, potential forms! Let everything vibrate in me with the universal anxiety of the beginning, just awakening from nothingness!

— Emil Cioran

Ours is a world in constant flux. Life unfolds in a fog of conscious and unconscious perceptions, a chaos animated by infinite speeds. There is no distance, no proximity, no sense of foreground or background. We move through physical and virtual spaces with limbs still nimble – touch, taste and smell intact — but our eyes do not see, they reflect. The world comes to a halt as a pure staccato, a vision without space, without perspective, without context. Gilles Deleuze: “From chaos, Milieus and Rhythms are born. This is the concern of very ancient cosmogonies. Chaos is not without its own directional components, which are its own ecstasies”.

Philip Hoffman, Chimera

Canada 1996, 16mm, 15:00 min

“Chimera is Hoffman’s most understated film that explores his two most common themes: death and chaos. And it is perhaps his most immediate film dealing with frozen moments, life transitions and fragments of memory. The shots are in constant movement and it makes the image blurred a good portion of the time; periodically, a readable moment will appear, just briefly, and then the movement continues. It’s a statement in chaos at its most heightened state. The world is blurry with only snatches of clarity—it’s moving fast with only glimpses of calm. You never know exactly where you are or what is going on, except for fleeting moments.” (Janis Cole)

Jean–François Guiton, Tramage

France 1999, video, 12:00 min

“Rhythm is the theme as well as the form of this video. Its elements are constructed and played out through a time measure resembling the busy tempo of city life. To begin, stripes of light are drawn through the two sides of the black empty screen; their unpredictable crossings and untimely collisions lead to the appearance of an opening and closing tramway car door in the picture. Simultaneously, the rhythm unfolds in an unsynchronized sound bar. Squeaking, sucking, the noise of a passing train: all these different noises put together a soundtrack that sometimes falters, sometimes accelerates, diminishes and increases in volume, or simply falls into silence. Tramage’s interruptive and disruptive repetition of the city dweller’s impressions revives the moment of experience in our perception.” (Antonia Birnbaum)

Dietmar Offenhuber, Besenbahn

Austria 2001, video, 10:00 min

Images of the city of Los Angeles, which has been shaped by the history of motorization and where moving perception has come to be regarded as integral to natural perception. The repetition and temporal reordering of sequences creates a stream of images that can only be read through the speed of the travelling camera. According to Offenhuber, in its fragmentation of the continuum of perception “the subjective geometry which defines space through intervals of time” can remain submerged because it is already so familiar. A work that explores the forms of perception transmitted by technological media.

Scott Stark, Acceleration

United States 1993, video, 10:00 min

A snapshot taken in a moment of human evolution, where the souls of the living are reflected in the windows of passing trains. The camera captures the reflections of passengers in the train windows as the trains enter and leave the station, and the movement creates a stroboscopic flickering effect that magically exploits the pure sensuality of the moving image. Acceleration reads like a double motion study, examining the movement of its outward subjects (passengers and trains) as well as the camera’s own ability to produce illusions of motion different than those usually generated by the apparatus.

Makino Takashi, Still in Cosmos

Japan, 2009, 35mm to HD video, 19:00 min

“I do not think that the word ‘chaos’ means ‘confusion’ or ‘disarray’, rather I believe it refers to a state in which the name or location of ‘objects’ remains unknown. For instance, if a bird escapes from its cage, the world it discovers outside will appear to be chaos, but if it joins with a flock of other birds, it will gradually learn to apply ‘names’ to various places – a safe place, a dangerous place, etc., thereby creating cosmos (order). When watching a film, the viewers all sit in the same darkness and receive the same light and sound but each sees a different dream. I believe this symbolizes a reversion to their initial state, that when they look at total chaos through newborn eyes, they give birth to a new cosmos. I sincerely hope that the violent chaos that exists in still in cosmos will give rise to the same number of new cosmoses as there are viewers.” (MT). Music by Jim O’Rourke.

Stom Sogo, Sync Up Element

Japan/United States 2007, video, 23:00 min

“Since I was a teenager, I have an epileptic fit. I passed out twice in this year. It is like a memory flashback; wrapped by the various warm childhood images. In this movie, a bisexual boy and a girl are dancing, a kind of love. However; you may not see them though; a strobe light creates you to see the clear images inside of you. (…) All of my film and video pieces are in many ways the abstraction of feeling of people whom have been driven into a corner or stuck in their own maze. Sync Up Element is the cure vision in our data oriented digital lives. I mean I am not making a medicine but film viewing experience itself will open up many discoveries to our natural details in our memories” (SS). The soundtrack is based on a composition by William Basinski.

———————————————————————————————————————————————————

Out of the Present

Sunday 18 October, 13:00, Film Theater ’t Hoogt, Hall 1

So many things have changed. But what amazes me the most is: just now it was night, and now it is day and the seasons just fly by. I’d say that is the most impressive thing you see from up here.

— Sergei Krikalev

Andrei Ujica, Out of the Present

Germany/Russia/France1995, 35mm, 96:00 min

In May 1991 Soviet astronaut Sergei Krikalev left Earth for the space station Mir. 310 days later – 5 months longer than initially foreseen – he returned home, which in the meantime was no longer the Soviet Union but Russia. Krikalev’s experience throws a light not only on the acceleration of history in his country, but also on the acceleration of reality, which according to speed philosopher Paul Virilio leads to the “time accident”. Mir is no longer a monument under the stars but a co(s)mic ruin that symbolises the failure of the progressive myth of mankind’s conquest of the stars.

Thanks to: Mark Toscano & May Haduong (Academy Film Archive), Michaela Grill & Gerald Weber (Sixpack), Kim Leroy, Pieter-Paul Mortier, Marie Logie, Dirk Deblauwe (Courtisane), Dominic Angerame (Canyon), Mike Sperlinger & Adam Jones (LUX), Christophe Bichon (Lightcone), Toril Simonsen (Norwegian Film Institute), Michelle Silva (Conner Foundation), Anika Tannert (imai), Kati Nuora (Crystal Eye), Otto Suuronen (Finnish Film Foundation), Hanna Maria Anttila (av-arkki), Christophe Calmels (Films Sans Frontières), Claartje Opdam (Filmbank), Jane Balfour, Mark Lewis Studio, Heure Exquise, Julia Sosnovskaya, Jan Mot and Heidi Ballet (Jan Mot Galerie), Joke Ballintijn and Theus Zwakhals (NIMK), ZKM, Karl Winter (Arsenal)