ARTIST IN FOCUS: Robert Fenz

In the context of the Courtisane Festival 2011 (Gent, March 30 – April 3 2011)

Robert Fenz (1969, Ann Arbor, Michigan) is one of the most singular and committed filmmakers breathing new life to avant-garde film traditions today. Fenz’s films, mostly shot in black and white 16mm, have a rare energy and restless beauty that recalls both the jazz-inspired imagery of New York School photographers such as Roy DeCarava, but also the landscape films of one of Fenz’s former teachers, Peter Hutton, and the documentary work of Johan van der Keuken and Chantal Akerman, some of whose recent film works have actually been shot by Fenz himself. His films are personal and poetic portraits of people and places he encountered during his many travels in countries such as in Cuba, Mexico, Brazil and India. “Though they can be viewed as non-fiction works, objectivity is not one of their pretences. Images not words are central and the primary means by which their ideas are articulated. In each case, meaning is determined by three factors, ‘intention, circumstance and chance’ ingredients filmmaker Robert Gardner describes as central to the making of a non-fiction film.” Fenz’s attitude towards filmmaking has also been greatly influenced by jazz improvisation, especially by the work of trumpeter Wadada Leo Smith, under whom he studied. “Studying music with Leo reinforced my belief that I needed to go into the world with an idea – do research on a subject and arrive at a place where I would be prepared to adapt and change the film completely, in the moment”. The most celebrated result of this approach is Meditations on Revolution, a series of five films made over seven years (1997-2003), exploring the basic theme of revolution in its purest qualities: the revolution inscribed in rural and urban spaces, steeped in hollowed and smiling faces, dancing on the rhythms of a world in constant transition. Robert Fenz has just completed one new film which will have its European premiere at the festival: The Sole of the Foot.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

SCREENING-PERFORMANCE

Robert Fenz / Wadada Leo Smith

Kunstencentrum Vooruit, FRI 01.04.2011, 20:30

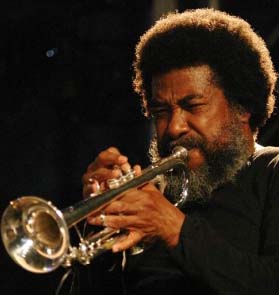

The paths of Robert Fenz and trumpeter/composer Wadada Leo Smith (1941, Leland, Mississippi) crossed ways for the first time when Fenz decided to study musical improvisation at the California Institute of the Arts. The lessons he received from Leo Smith who teaches “African-American improvisation music” there still resonate today in the films of Robert Fenz. Smith’s influential ideas go beyond the strictly musical: what matters most is the creative and subjective exploration of connections between colour and rhythm, sound and space, texture and style. It’s a philosophy that he developped in the 1960s when, together with Anthony Braxton, Leroy Jenkins and other members of the ‘Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians’ (AACM), he transferred the focus of the American Free Jazz to an outspoken intellectual research on music as language and system. Smith introduced at the time the concept of “rhythm units”, which would be later formalised as a graphic notation system known as the “Ankhrasmation”. “I was never interested in metrical or harmonic progression. I always looked at how you make music without all those things everybody has inherited.” It’s this singularity that has established him as one of the most respected musicians of his generation and has led to affinities with Cecil Taylor, Marion Brown and many others. With his unique, lyrical form of phrasing in which what can’t be heard is as important as what is heard, he has left an indelible and unmistakable mark on the jazz music of the past decades. This performance offers a unique chance to see him at work in one of his favourite settings, the combination of an orchestration of light with a new dimension of sound.

The Sole of the Foot

US, 2011, 16mm, colour, sound, 34’

ubiety [juːˈbaɪɪtɪ]

n the condition of being in a particular place

[from Latin ubī where + -ety, on the model of society]

Origin of the English word “PLACE”:

“Middle English, from Anglo-French, open space, from Latin platea meaning broad street, from Greek plateia (hodos), from feminine of platys broad, flat; akin to Sanskrit prthu broad, Latin planta sole of the foot. Latin planta sole of the foot is ultimately from an Indo-European word meaning ‘to spread,’ which is also the ancestor of the English word place. [Pre-12th century. – Latin plantare ‘plant in the ground’ – planta ’sole of the foot’]”

“Borders (and all the politics attending the drawing of borders) exist to keep some people in (citizenship) and others out. This film is an attempt to capture the presence of people otherwise denied the political right to be at home in some place that is their home, where they have their roots, where they have their being…. (Palestinians and Israelis; North Africans in France, Cubans on the island of Cuba (their right to rule themselves denied by foreign powers).” (RF)

Meditations on Revolution

Part I: Lonely Planet

US, 1997, 16mm, b/w, silent, 12’

Part II: The Space in Between

US, 1997, 16mm, b/w, silent, 8’

Part III: Soledad

US, 2001, 16mm, b/w, silent, 14’

Part IV: Greenville, MS

US, 2003, 16mm, b/w, silent, 29’

The first four films of series of five (the last one will be screened on Saturday) in which Fenz searches for the meaning and the resonance of the word “revolution” in Cuba, Brazil, Mexico and the Mississippi. “How can it be that this myth, that the entire history of the 20th century should have eliminated, hasn’t lost its power of evocation? (…) The revolution carries in itself the tireless influence of dreams, ideals and struggle. The films of Robert Fenz can never be subject to the principles of static analysis: their potential of subversion is always at work. However some traits are common to his entire oeuvre: the critical conscience, the political engagement (which differs from militantism), the desire to know what the shadows withhold, the passion for the other. Fenz reaffirms these prominent traits of his artistic humanist heritage innovating in the construction of a visual sensitivity which opens up elemental questions of idealism from concrete, sensitive and physical observation. Following the path of rhythm, creative improvisation and kinetic description, his cinematographic oeuvre develops a style that is founded on a profound faith on the power of the image – as a source of communication, as a critical tool, as an interior necessity.” (Gabriella Trujillo)

Crossings

US, 2006/07, 16mm, colour, sound, 10’

“Crossings is an abstract portrait of the border wall. Both sides are confronted. The film is a short installment on a larger project that investigates insularity in both geographical and cultural terms. It isalso my short reflection on From the Other Side, a film I worked on in 2002 by Chantal Akerman (filmed at the United States- Mexico border).” (RF)

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

SCREENINGS

FILM-PLATEAU, Sat 02.04.2010, 20:30

20:30 ROBERT FENZ SELECTION PART 1

Robert Fenz

Meditations on Revolution, Part V: Foreign City

US, 2003, 16mm, b/w, sound, 32’

The final film in Fenz’s series Meditations on Revolution. Dedicated to the director’s father, who immigrated to the United States after WWII and died in 1999. Foreign City studies New York as a place of immigration and displacement. Using abstract black and white images and actual city sounds which come in and out of synch, Fenz creates a magical foreign landscape in which the city is reconstructed through an imaginary plan, built on sensation. At the film’s center is a monologue by recently deceased artist-musician Marion Brown 11931-2010), whose proud, fatigued monologue fuses with haunting imagery of an alienating landscape.

Ken Jacobs

Perfect Film

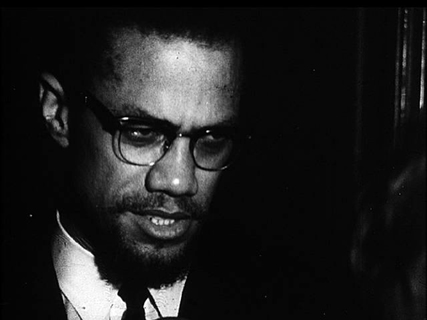

US, 1986, 16mm, b/w, English spoken, 22’

The rushes of a news report on the assassination of Malcolm X, just as they were found on a bin. “A lot of film is perfect left alone, perfectly revealing in its un- or semi-conscious form. I wish more stuff was available in its raw state, as primary source material for anyone to consider, and to leave for others in just that way, the evidence uncontaminated by compulsive proprietary misapplied artistry, ‘editing,’ the purposeful ‘pointing things out’ that cuts a road straight and narrow through the cine-jungle, we barrel through thinking we’re going somewhere and miss it all.” (KJ)

Johan Van der Keuken

Vakantie van de Filmer (Filmmakers Holiday)

NL, 1974, 16mm, colour, Dutch spoken, English subs, 38’

“In a small, depopulated village of the Aude province of France, an elderly couple confides to the ‘vacationer’s camera their memories of the past: war, illness, death…

The film is put together as a collection of autonomous images which, once combined, make up van der Keuken’s mental universe: family happiness, fragments of some of his earlier films, a homage to the saxophonist Ben Webster, two poems by the great contemporary poets Remco Campert and Lucebert, a portrait of the director’s grandfather, who taught him photography at the age of twelve… One of those small masterpieces one encounters by surprise…” (Jean-Paul Fargier)

22:30 ROBERT FENZ SELECTION PART 2

Jean-Marie Straub & Danièle Huillet

Trop tôt, trop tard (too early, too late)

FR, 16mm, colour, French spoken, English subs, 1981, 105’

“Opening upon one of the most memorable shots ever filmed, Trop tôt, trop tard is an essay on the often tentative, yet urgent conditions of revolution. Shot in France and Egypt, the film employs a diptych structure as it attempts to (quite literally) catch the wind of past revolutions, using the writings of Friedrich Engels and Mahmoud Hussein. Shooting first in the busy roundabout of Paris’s storied Place de la Bastille, then in the outlying countryside where the seeds of revolution were once sewn, Straub and Huillet describe how the French peasants revolted ‘too early’ and succeeded ‘too late’. Alongside landscapes shot near the Nile and its delta, an Arab intellectual relates the history of the peasant resistance during the occupation by the British, who similarly employed bad timing. Much has been written about the film’s ebb and flow structure, especially by Serge Daney, who observed its musical and ‘meteorological’ play not seen since the silent era. ‘Trop tôt, trop tard is, to the best of my knowledge, one of the rare films, since Sjöström, to have filmed the wind’.”(Cinematheque Ontario)

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

OPENING NIGHT OF THE FESTIVAL

KASK, Wed 30.03.2011

Amongst others, Robert Fenz’ Vertical Air will be shown on the opening.

Robert Fenz

Vertical Air

US, 1996, 16mm, b/w, sound, 26′

The result of an experiment with sound and image, composition and improvisation, in collaboration with Wadada Leo Smith, who will perform live at Vooruit on Friday. “The musical system in Vertical Air allows not only the predetermined to blossom but also the improvised to emerge. Improvisation and its cinematographic equivalent manifest themselves from the moment of shooting, and through the composition of the frame to the editing process itself. Verticality is drawn from the simultaneity of both arts, the creation of independent melodic lines that are echoed by the editing of images traversing in a bird’s eye view the vastness of the North American territory”. (Gabriela Trujillo)