In the context of Courtisane Festival 2024 (Gent, 27 – 31 March 2024), with the support of KASK & Conservatory / School of Arts.

How to think dub cinema? How to think dub in, or as, or with, cinema? How, and in what ways, to think cinema by way of dub? How, and in which ways, does dub, understood not as a genre but, instead, as a sonic process that undoes the body of song, unmake the temporal structures of film?

In which ways does film invite thought that registers some of the ways in which dub, understood not only as sonic process but as cinesonic process, dramatises the unbelonging of black film to, or for, the institutions of the aesthetic, the ancestral, the archival, the auteurist, the authentic, the avant-garde, the bodily, the communitarian, the formal, the gendered, the generic, the historical, the militant, the narrative, the nation, the oral, the poetic, the political, the popular, the racial, the resistant, the struggle, the sexual or the traditional called upon by thought to organise the coherence of cinema?

Think of Thinking with Dub Cinema as two days of study, a film programme and a dub session devoted to questioning these questions. An invitation to study that dedicates itself to a practice of listening to cinema enabled by watching Handsworth Songs (Black Audio Film Collective, 1986).

Across study sessions led by Kodwo Eshun, Louis Henderson and Lynnée Denise, Thinking with Dub Cinema departs from an invitation to thought that attends to Handsworth Songs. Each session invites attendees to attune practices of watching, reading and listening towards developing a dub methodology for the imagination of auditory blackness, black audition, collective audition and filmic collectivity announced by Handsworth Songs.

Think of Thinking with Dub Cinema as a convening around an idea of dub cinema proposed, initially, by Greg Tate in 1988 and, subsequently, by Okwui Enwezor in 2007. In ‘Never Mind the Sex Pistols, Here Comes Sankofa’ published in The Village Voice on 30th August 1988, Tate wrote that:

“Black Audio Film’s Handsworth Songs is dub cinema — dub, for the uninitiated, being that form of reggae where the lead vocal track is removed, and the foreground space filled with regenerated and decaying sounds bent on invoking a mythic African past and future. Ostensibly a documentary, its free-floating and spectral treatment of historical footage testifies to the mystique of the black British citizen while critiquing the commercialization of the black image. Handsworth Songs is a compressed chorus of black British voices, whose foregrounding puts white media and the police in the position of being Other.”

In ‘Coalition Building: Black Audio Film Collective and Transnational Post-colonialism’ published in The Ghosts of Songs: The Film Art of the Black Audio Film Collective edited by Kodwo Eshun and Anjalika Sagar in 2007, Enwezor argued that:

“Though ostensibly addressing the issues of policing, Handsworth Songs reflects more profoundly the agency of the oppressed; it narrates their stories, not purely from the point of view of the event from which it derives its name, but equally through an archaeology of the visual archive of minoritarian dwelling in Britain. As is often the case in Black Audio Film Collective’s work, the ghosts of those stories inform the notion of a historically inflected dub cinema whose spatial, temporal and psychic dynamics relays the scattered trajectories of immigrant communities.”

Think of Thinking with Dub Cinema as an invitation to hear the ‘free-floating and spectral treatment of historical footage’ proposed by Tate and the ‘notion of a historically inflected dub cinema’ advanced by Enwezor as suggestions or, better still, as suggestures, to use Ian Penman’s term, for imagining a cine-poesis of the echo and a cine-practice of the version.

To hear Handsworth Songs as dub cinema is to elaborate upon the ways in which Handsworth Songs practices its versioning of cinema and its cinema of the version. To hear Handsworth Songs in and as a cine-mix is to attend to the ways in which Handsworth Songs versions film. To hear dub cinema in Handsworth Songs is to listen for the latent dimensions of the retroactive and the proleptic that become available for thought in the sounds and the images deployed by Handsworth Songs.

To hear Handsworth Songs from the place of the queer epistemology of Isaac Julien’s Territories, the television ballad of Philip Donnellan’s The Colony, the negrophobic Pathé newsreel of Our Jamaican Problem and the funerary poetics of Sir Collins & The Versatiles is to orient thought towards the ways in which Handsworth Songs summons archives for the sake and the stake of struggles that threaten the futures of the memories of black lives and deaths.

Think of Thinking with Dub Cinema as an invitation to elucidate the ways in which Handsworth Songs announces a cinema of unbelonging and unsettlement. An invitation to expound, expand and explicate some of the ways in which cinema dramatises its dub acoustemologies, its dub adjacencies, its dub affinities, its dub cosmologies, its dub economies, its dub epistemologies, its dub morphologies, its dub ontologies, its dub poiesis, its dub psyches.

Curated by Kodwo Eshun and Louis Henderson

In the context of the research project Echoes of Dissent (KASK & Conservatory / School of Arts Gent)

With the support of the Committee for Contemporary Art, KU Leuven and LUCA School of Arts, Film Department campus Brussels

In collaboration with Auguste Orts and argos

——————–

STUDY DAYS

Kodwo Eshun is a filmmaker, theorist and artist. In 2002, he co-founded The Otolith Group with Anjalika Sagar. They work by looking in the key of listening across media, observing a research-based methodology that studies events, archives, movements, compositions, materials, performance, vocality, and space-time in moving and non-moving image, sound, music and text. He is author of works such as Dan Graham: Rock My Religion (Afterall, 2012) and More Brilliant than the Sun: Adventures in Sonic Fiction (Quartet Books, 1998), and co-editor (with Anjalika Sagar) of The Ghosts of Songs: The Film Art of the Black Audio Film Collective (Liverpool University Press, 2007). He is a lecturer in Aural and Visual Culture at Goldsmiths, works as a curator and writes regularly for magazines and journals.

Louis Henderson is a filmmaker and writer who experiments with different ways of working with people to address and question our current global condition defined by racial capitalism and ever-present histories of the European colonial project. Henderson‘s films and installations are shown regularly in various international film festivals, art museums and biennials and are distributed by LUX and Video Data Bank. His writing has been published in both print and online in books and journals. At present, Henderson is a doctoral candidate at the École Nationale Supérieure d‘Arts de Paris-Cergy. His research looks into the riverscapes of the East of England and Guyana through “spiral retellings” of the works of Wilson Harris and Nigel Henderson.

A global practitioner of sound, language, and Black Atlantic thought, Lynnée Denise is an Amsterdam-based writer and interdisciplinary artist from Los Angeles, California. Shaped by her parent’s record collection and the 1980s, Denise’s work traces and foregrounds the intimacies of underground nightclub movements, music migration, and bass culture in the African Diaspora. She coined the term DJ Scholarship in 2013, which explores how knowledge is gathered, inter- preted, and produced through a conceptual and theoretical framework, shifting the role of the DJ from a party purveyor to an archivist and cultural worker. A doctoral student in the Department of Visual Culture at Goldsmiths, Denise’s research contends with how iterations of sound system culture construct a living archive and refuge for a Black queer diaspora. She just published her debut book, Why Willie Mae Thornton Matters (the University of Texas Press), a narrative journey of reclamation that intricately details and humanizes the full life, musical contributions, and cultural impact of Willie Mae Thornton.

SESSION ONE

27 MARCH, 2024 – 10:00

KASKCINEMA

SESSION TWO

27 MARCH, 2024 – 14:00

KASKCINEMA

SESSION THREE

28 MARCH, 2024 – 10:00

KASKCINEMA

SESSION FOUR

28 MARCH, 2024 – 14:00

KASKCINEMA

——————–

SCREENINGS

SCREENING ONE – The Terror and the Time

28 MARCH, 2024 – 22:15

PADDENHOEK

The Terror and the Time

Victor Jara Collective / Rupert Roopnaraine, GY, 1979, 16mm, 70′

The terror is British colonialism in Guyana; the time is 1953, the year of the first elections under a provisional democratic constitution. Stylized scenes photographed throughout Georgetown accompany the poetry of Martin Carter to convey a sense of intense political reform against poverty, repression and silence. The film unfolds against the interna tional backdrop of the 50s: the growth of foreign economic and military interests in the Caribbean basin, the coronation of Queen Elizabeth, the Mau Mau revolts in Kenya, the Cold War, and the U.S.’ covert wars against Cuba, Malaysia, Vietnam, Iran and Nigeria.

“In his forward to Poems of Resistance by his comrade and compatriot Martin Carter, the great Guyanese writer Eusi Kwayana, implies that poetry is criticism. This sense of criticism held and released in and before art animates The Terror and the Time. The film offers poetic practice, historical criticism, and critical historiography in a rehearsal of sound, image, ground, and aspiration… Rupert Roopnaraine, a key figure in the Victor Jara Collective, suggested that the product betrays the process so that the film’s unfinishedness is given in accord with anticolonial struggle. As he argues what is important is that the strug gle remains. And what remains is the unstill consistency of the cartman and the dark, glimpsed by and given in criticism, through the absolute dissolution of the poem and the poet, the filmmaker and the film.” (Stefano Harney and Fred Moten)

Followed by a conversation with Lewanne Jones, Ray Kril and Susumu Tokunow, members of the Victor Jara Collective

SCREENING TWO – Handsworth Songs / Thames Film

30 MARCH, 2024 – 11:00

PADDENHOEK

Handsworth Songs

Black Audio Film Collective / John Akomfrah, UK, 1986, 16mm to digital, 59′

A cinematic essay on race and civil disorder in 1980s Britain, Handsworth Songs takes as its point of departure the civil disturbances of September and October 1985 in the Birmingham district of Handsworth and in the urban centres of London. Running throughout the film is the idea that the riots were the outcome of a protracted suppression by British society of black presence. The film portrays civil disorder as an opening onto a secret history of dissatisfaction that is connected to the national drama of industrial decline. “To make sense of the debris in Handsworth, BAFC had to reconstitute the fragments, and in doing so, words, sound and image came alive in an audio/visual style.”

“The feeling of disjuncture is reflected not only in the jump cuts of the film’s narrative discontinuity — moving between archival photographs, newsreel fragments, media reportage, and on-site interviews — it is also deeply anchored by the sombre aural pulse, the disjunctive syncopation of the snare drum beat, the mournful reverb of the dub score that sustains a quiet rage. Though ostensibly addressing the issues of policing, Handsworth Songs reflects more profoundly the agency of the oppressed; it narrates their stories, not purely from the point of view of the event from which it derives its name, but equally through an archaeology of the visual archive of minoritarian dwelling in Britain. As is often the case in BAFC’s work, the ghosts of those stories inform the notion of a historically inflected dub cinema whose spatial, temporal and psychic dynamics relays the scattered trajectories of immigrant communities.” (Okwui Enwezor)

Thames Film

William Raban, UK, 1986, 16mm, 66′

By filming from the low freeboard of a small boat, William Raban attempts to capture the point of view of the river Thames, tracing the 50 mile journey from the heart of London to the open sea. Interspersed with images from Brueghel the Elder’s painting The Triumph of Death and T.S. Eliot reading Four Quartets, this contemporary view is set in an historical context through use of archival footage and the words of the travel writer Thomas Pennant, who followed exactly the same route in 1787.

“This is a vision of the dark Thames, of ‘Old Father Thames’ as an awful god of power akin to William Blake’s Nobodaddy; and, in Blake’s poem, Jerusalem, ‘Thames is drunk with blood’. In this film there is something fearful about the river, something monstrous, recalling Conrad’s line in Heart of Darkness that ‘… this also has been one of the dark places of the earth’. Walking along the banks of the Thames, down river, approaching the estuary, it is possible to feel great fear. One of the possible derivations of the word Thames itself is tamasa meaning ‘dark river’; the word is pre-Celtic in origin, so we have the vision of an ancient, almost primeval, time. And yet there is beauty and sublimity in terror. Raban has learned something from the great artists of the river, such as Turner and Whistler, and portrayed the Thames as clothed in wonder.” (Peter Ackroyd)

SCREENING THREE – Territories / Emergence / In the Shadow of the Sun

30 MARCH, 2024 – 22:15

SPHINX CINEMA 3

Territories

Sankofa Film and Video Collective / Isaac Julien, UK, 1984, DCP, 25′

Looking at the history of Carnival in Britain as a subversive phenomenon, Territories views cultures and languages as markers that attempt to define the boundaries of both metaphorical and real territories. The film juxtaposes — and often superimposes — original and archival materials: footage of festive street life and rioting during Carnival, of police surveillance, of white and black British men and women exchanging desiring and alienated glances while vying for control of social space, and of the desolate urban evidence of abandonment and neglect.

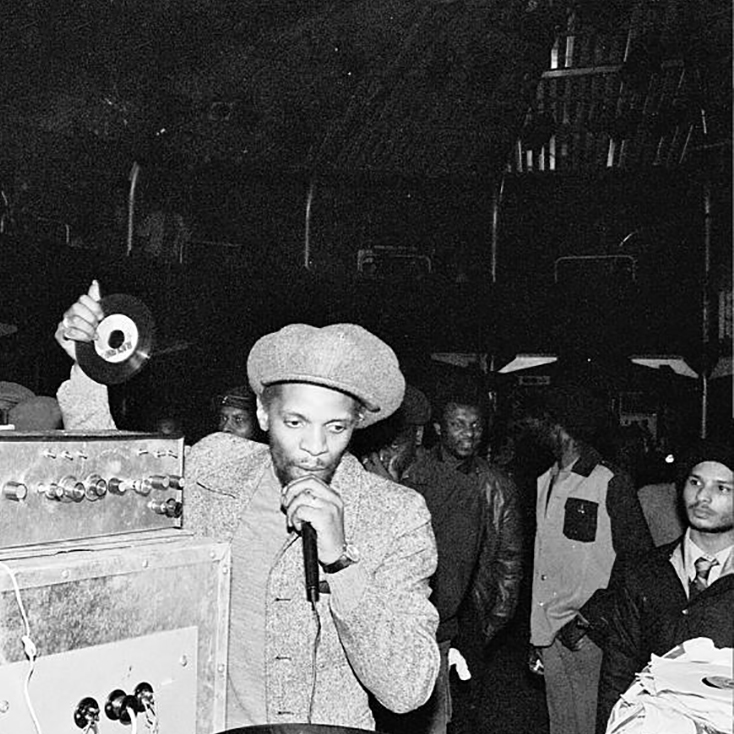

“In Territories, the growing power of organized sound and music counterpoints the visual montage and is articulated with it aesthetically. Our narrators sit at a Steenbeck editing machine, underscoring their responsibilities as mediators, but the DJs and MCs who make up People’s War are not positioned at that distance. Under the time-stretching impact of what we must call a dub aesthetic — one grasping the shock that only the unintelligible can communicate — the film demands to be encountered as a remix. Its repeated phrases, oscillations, and orchestrations depart from reggae; their relocation to the gray northern metropolis has opened them to the emergent power of hip-hop and what we used to call ‘electro’. … Here is the demotic pulse of a truly populist modernism and we do ‘Feel Like Jumping’. Its dissident spirit is propelled by the energy of ritual repetition, of ceaseless versioning. “ (Paul Gilroy)

Emergence

Pratibha Parmar, UK, 1986, DCP, 18′

Pratibha Parmar made her first video work with the help of Black Audio Film Collective as “a way of saying something about the emergence of Black women and Asian women as cultural artists and cultural activists”. Emergence interweaves the diasporic voices of four women of color: Audre Lorde, Mona Hatoum, Sutapa Biswas, and Meiling Jin. Transporting diasporic identities across a landscape of white noise and silence (soundtrack by Trevor Mathison), alienation, and fragmentation, Emergence moves toward the reintegration of speaking, performing subaltern subjects.

“Emergence is a performative multi-voiced and multi-enacted ritual visual poem that moves women of color, as the voice-over states, ‘from yesterday’s silence to tomorrow’s dreams’. Woman as speaking subject, gazing subject, interrogating corporeal performative subject owns spatiality in an arena that once depended upon her invisibility, her silence, and the suppression of her performing body. Emergence works to recover subjected forms of knowledge. Parmar invokes a performative ethnographic to move across the landscapes of colonial division, in the process underscoring the need for an ‘ethnographic ear’, as defined by Anglo-Asian cultural critic Jenny Sharpe. Sharpe finds that ethnographic listening ‘exists between and not within cultures … beside every native voice is an ethnographic ear’.” (Gwendolyn Audrey Foster)

In the Shadow of the Sun

Derek Jarman, UK, 1981, 16mm to DCP, 54′

In the Shadow of the Sun draws upon Derek Jarman’s interest in alchemical processes as a metaphor for reprocessing Super-8 film. Originally called English Apocalypse, the film’s final title is derived from a 17th Century alchemical text that used the phrase as a synonym for the philosopher’s stone — the highly sought substance that turns base metals into gold and silver. The film, with a score by Throbbing Gristle, was intended as a step toward the idea of an ambient video, that like its musical counterpart, was designed to enhance an environment.

“In the Shadow of the Sun is a fire film, an English Apocalypse… related to John Dee and alchemy where the distinction between words and things is obscured by the identification of symbols with things… The images are fused with scarlets, oranges and pinks. The degradation caused by the refilming of multiple images gives them a shimmering mystery/energy like Monet’s ‘Nympheas’ or haystacks in the sunset. There is no narrative in the film. The first viewers wracked their brains for a meaning instead of relaxing into the ambient tapestry of random images. The language is there and it is conveyed — and you don’t know what you have to say until you’ve said it. You can dream of lands far distant.” (Derek Jarman)

——————–

LATE NIGHT DUB SESSION

29 MARCH, 2024 – 23:00

DE ROES (DONKERSTEEG 4)

A skeletal promise or a spectral insistence

by Louis Henderson

A Late Night Dub Session.

Sound system by Sailah Soundsystem