“the reason I love movies is because I experience them as music”

— Toru Takemitsu

I’ve been intrigued by Toru Takemitsu’s film music ever since I saw Hiroshi Teshigahara’s Woman in the Dunes (1964) for the first time. Takemitsu’s score relies almost entirely on a string ensemble, recorded, rearranged, pitched, distorted, alienated. The sounds, alternately shrill, harsh and menacing, form a perfect soundscape for the austere allegory of the story, written by Kobo Abe – a narrative about a man and woman who are bound to labor together at the bottom of a sand dune, continually digging sand, supposedly in order to protect some unseen village nearby. In Charlotte Zwerin’s 1994 documentary Music for the Movies: Toru Takemitsu (see below), Teshigahara has commented that this film had not two, but three main characters: the man, the woman, and the sand. “The sand has its own identity and without Toru’s help, we never would have been able to realize this fully.” In another interview, the director said “He was always more than a composer. He involved himself so thoroughly in every aspect of a film—script, casting, location shooting, editing, and total sound design—that a willing director can rely totally on his instincts.” Takemitsu meticulously checked all the sounds recorded for the film – the dialogue as well as the concrete sounds. “There are so many different sounds in a film, but he checked every single one and would say, we can scrap this noise and hear music here, or vice versa. Also, we tried to mechanically process the concrete sounds.”Peter Grilli writes about Woman in the Dunes:”‘composed’ music is only part of Takemitsu’s unique contribution to the film. The weird environment is the dominating quality of the film, and, recognizing this, Takemitsu gives life to the sand through sound. It is there at all times, even when a scene seems completely silent. The soft, barely audible sizzle or hiss or patter of sand—dripping, shifting, and constantly in motion—inhabits every moment of the film, as it does every moment of the protagonists’ terrifying existence. And it is through the subconscious quality of sound that the woman’s persistent reply to the man’s fearful questions—“It is the sand”—develops its total, all-enveloping meaning”. And David Toop: “Surfaces are eroticised; rationalism and the bureaucratic order of modern life are pitted against animism and the inexorable rhythms of nature, these transformations and oppositions echoed by Takemitsu’s granular, eerie musical scores of sudden distorted shocks and attenuated, fibrous tones: music as skin tones.”

Fragment:

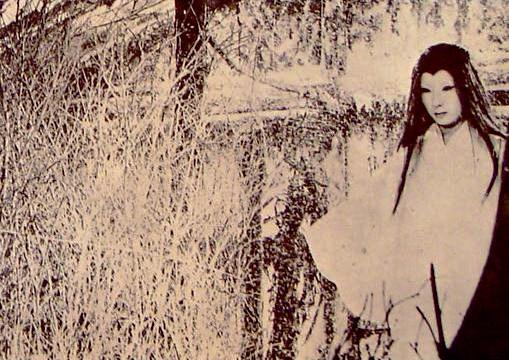

The three of them – Teshigahara, Abe and Takemitsu – also worked together on Pitfall (1962), The Face of Another (see still) (1966), and Man Without a Map (1968), all powerful works that move fluidly between abstraction and narrative, the multiple echoes of sound and image, exploring issues of identity, human existence, and the alienation of modern man in urban society, symptoms of an existential dilemma that was very present in post-war Japan. “Because of World War II,” wrote Takemitsu, “the dislike of things Japanese continued for some time and was not easily wiped out. Indeed, I started as a composer by denying any ‘Japaneseness’.” Takemitsu, a musical autodidact, first looked to European composers for inspiration: Debussy, Ravel, Berg and Olivier Messiaen, and later also the North-American avant-garde, especially Cage and Feldman (of who he wrote:”Whenever I hear his music I think of its tactile quality, of his ears “hearing” the sounds”). Like them he discovered that organised music, noise and concrete sounds were all part of the musical spectrum. “One day in 1948 while riding a crowded subway,” he wrote in A Personal Reflection, “I came up with the idea of mixing random noise with composed music. More precisely, it was then that I became aware that composing is giving meaning to that stream of sounds that penetrates the world we live in.” This epiphany convinced him that contemporary music was self-enclosed within the systematic rigour of its own language. His incorporation of concrete sound and urban noise was an effort to reach out to people who heard these sounds as part of their daily lives. Film director Masahiro Shinoda – who worked with Takemitsu on films like Samurai Spy (1965), Double Suicide (1969), The Petrified Forest (1973) and Banished Orin (1977) – said: “I believe what fascinated him most about film was his keen interest in the overlap of real sound and the soundtrack along the sequence of the film. The rustling of silk, footsteps, the opening of a shoji sliding door, and notes from musical instruments – they were all “music” for Takemitsu. Even before musical instruments make sound into “music”, there were sound sources, and such sound could turn into “music”, or turn into “film/images”. Teshigahara:”He tried to create a self-contained world that ran parallel to the image yet fused them together.”

Takemitsu wrote about a hundred soundtracks and worked with many of the most interesting post-war “new wave” directors in Japan – including Nagisa Oshima, Masaki Kobayashi, Susumu Hani, Akira Kurosawa, Shohei Imamura and Kon Ichikawa, which, according to David Toop, “allowed him the opportunity to explore the dramatic impact of genre dislocations, anachronistic juxtapositions, stylistic borrowing, gorgeous melody, extreme noise, alienation and shock.” The music he composed for these films was extremely diverse and often unexpected, ranging from harsh prepared piano scrapes and thuds, ravishingly pretty Fender Rhodes jazz piano and German drinking songs, to eerie drones, romantic strings, accordions, and even a Burt Bacharach influence (notably in Kurasawa’s Dod’es-kaden). In The Man without a Map, for example, he used samples of Elvis Presley’s ‘I Need Your Love Tonight’, “torn in gouts of tortured noise out of a landscape of shuddering, groaning drones, intercut with Vivaldi’s Violin Concerto in C Minor”. Takemitsu was also fascinated with traditional Japanese instruments such as the koto, biwa, shakuhachi and sho, which were almost as obscure and mysterious to him as they were to foreigners. He used the biwa – a loosely strung four-string lute fitted with only four or five frets and struck with a huge triangular plectrum – in wonderful films such as Masaki Kobayashi’s Harakiri (1962) and Kwaidan (1964). “The major characteristic that sets it apart from Western instruments,” he wrote, “is the active inclusion of noise in its sound, whereas Western instruments, in the process of development, sought to eliminate noise. It may sound contradictory to refer to “beautiful noise”, but the biwa is constructed to create such a sound.” Toop writes: “The large plectrum, like a sharpened hammer, is appropriate to the creation of ‘beautiful noise’. The entire instrument is difficult. The player must focus on single sounds, their subtle variations, the silence that precedes them, the decay of the note into nothingness. An examination of ma – the Japanese word signifying an interval in time and space – is essential to an understanding of biwa repertoire and the work of Takemitsu.” In Charlotte Zwerin’s documentary Donald Richie comments: “Emptiness is not there until something is in it.” The sounds define the silence. “Something pure only becomes interesting when combined with something coarse”, Takemitsu says in the documentary, “writing music is like getting a passport – a visa to freedom, a liberty passport.”

I found this documentary online, on the YouTube channel of Edward Lawes. The compression is awful, but it’s really a nice introduction into the world of Takemitsu (Charlotte Zwerin (1930 – 2004) is an acclaimed director who has worked with the Maysles brothers). Interview subjects includes Takemitsu himself (before his death in 1996) and several directors, including Masaki Kobayashi (who died the same year), Hiroshi Teshigahara (+2001), and Masahiro Shinoda. It includes fragments from films such as Shinoda’s Double Suicide (notice the turkish flute on the soundtrack), Kurasawa’s Ran (Takemitsu wanted to use stylised voices on the soundtrack, but Kurasawa was too obsessed with having a Mahler sound), Yoji Kuri’s animated film Ai (this soundtrack consists of a magnetic piece for two voices, one male and one female, both repeating the Japanese word ai, or love, in a variety of intonations, speeds and pronunciations), Kobayashi’s Kwaidan (to generate an “atmosphere of terror”, Takemitsu used the sounds of real wood) and Tokyo Trial (a 4 hour long documentary for which Takemitsu only used 9 minutes of music). There are some touching moments, like when Takemitsu muses about the time when he, as a 16 year old junior high school student, was drafted to the mountains to help with the construction of a food distribution base. The war was in its final year and in those desperate times, only martial music and patriotic songs were allowed. One day, secretly, a draftee played a record of a French chanson – Lucienne Boyer’s ‘Parlez Moi d’Amour‘. Takemitsu was so moved that he decided on the spot that, if the war should ever end, he would dedicate his life to composing music. The documentary concludes with a beautiful segment in which he talks about the influence of nature, and especially the sense of time and color in japanese gardens, on his music – underscored by a fragment from the documentary film Dream Window (directed by John Junkerman and written by Peter Grilli). Takemitsu once said about Japanese Gardens: “In the end, each element does not exist individually but achieves anonymity in a harmonious whole, and that is the kind of music I like to create. It glows in the sun, the colors shift when it rains, and the sound changes with the wind.” When asked if he were ever similarly inspired by a Western garden, he cited an experience at the Alhambra in Granada, Spain. “Since music for me is not symmetrical, I did not like the regularity of the garden at all,” he said. But suddenly, as he stood there, a woman walked quickly through the arcade and a breeze riffled the surface of the pool. “Only then,” he said, “the music came.”

part 1

part 2

part 3

part 4

part 5

part 6

Most of the films mentioned are available on DVD now, so I urge you to go find them. Some of the soundtracks were released in the early 1990s, as a Japan-only edition of six cds (a reissue on an earlier vinyl version). In 2006, a box edition, featuring these cds plus one with audio documents and interviews, was released and distributed, again only in Japan. To the best of my knowledge it is already out of print (let me know if I’m wrong!), but some parts are available here. In 1997 Nonesuch released a CD entitled The Film Music of Toru Takemitsu, with ten pieces that were selected by Takemitsu himself, in the months before he died. The pieces were performed by London Sinfonietta, conducted by John Adams. You may also want to check out some of the tape and musique concrète pieces that Takemitsu created in the NHK studio in Tokio in the 1950’s, especially Vocalism AI and Sky, Horse, and Death. About the latter David Toop writes: “The piercing aerial pitches and sudden percussive shocks of Sky, Horse, and Death made a link between the qualities of Japanese instruments such as hichiriki, sho, biwa and shakuhachi, and the radical new possibilities of transforming concrete sounds offered by magnetic tape and studio processing. Created for a radio drama in 1954, the piece is shamanistic in its imagery and intensity, anticipating Takemitsu’s work in cinema through the wildness of its dramatic movement and spatial contrasts, the mercurial sensations of realism that burst through a forest of otherworld sounds”.

Finally, this is the introduction to the The Film Music of Toru Takemitsu CD, written by Donald Richie…

“FROM 1956 , when he wrote the music for Ko Nakahira’s Kurutta Kajitsu (Crazed Fruit), until the year of his death, forty years later, Toru Takemitsu completed ninety-three film scores. When asked why he chose to write so extensively for the cinema, Takemitsu responded that he loved the movies, and “the reason I love movies is because I experience them as music.”

In film Takemitsu found a structure analogous to that of his own discipline. When he would travel abroad, he always went to the movies even (or especially) it he did not know the language of the country. “I sense something about the people there,” he once said. “In film I can see their lives, and feel their inner lives. As I watch the images on the screen, even without knowing the language, I feel I can understand the people – it’s a musical way of understanding.”

This led in turn to a way into the outside world. “Writing music for films,” according to Takemitsu, “is like getting a visa to freedom.” Not only did films offer him images of a world other than his own, there was also the challenge of matching his vision of this world to that of the film’s director. And there was the task of making the result a whole, where image and sound combined to create a reality where each alone could not.

This ambition admirably fit Takemitsu’s sensibility. He wanted, he wrote in his collection of essays, Confronting Silence, “to free sounds from the trite rules of music, rules that are stifled by formulas and mathematical calculations. I want to give sound the freedom to breathe… In the world in which we live, silence and unlimited sound exist. I wish to carve that sound with my own hands.”

Part of Takemitsu’s strong affinity for the cinema stemmed from the vitality of the medium. “I don’t like things that are too pure or too refined,” he said. “I am more interested in what is real, and films are full of life. For me, something pure becomes interesting only when it is combined with something coarse.” This something coarse but vital provoked an immediate reaction. “As I look at a film’s rushes, if it is a good film – even if there is no dialogue, no sound – I often feel I can already hear the music.” It is this heard sound, the sound that came to him from the moving images of a film, that Takemitsu then sought to capture in his score.

The film director Hiroshi Teshigahara, one of those with whom Takemitsu frequently collaborated, observed the process closely. “Of the many kinds of film composers, most look at a movie only when it is nearly finished, and then they think about where to add music, But Takemitsu immerses himself in the film right from the start. He watches it being shot, he turns up on location, and often visits the studio. His involvement with the film parallels that of the director … In his music he must find something unique for each film he works on. He’s not one of those composers who can simply pull music from a set of drawers in his head … As he watches the rushes for my films, he bounces his ideas off of them. This way his music can more fully enhance a scene: his placement of the music gives life to things that weren’t expressed in the images alone.”

Teshigahara gives as an example the music Takemitsu provided for Woman in the Dunes. “That film had three main characters: the man, the woman, and the sand.” The composer’s task was to find an aural parallel to that environment. “What is important is first to establish a sound,” Takemitsu said, “a sound that leaves a strong impression.” For Woman in the Dunes, the sound was a dry, percussive breathing or hissing, with portamento strings like the sliding sand itself. No pedal points, no security anywhere. “Though I used real instruments, their sounds were altered electronically. By suddenly raising the pitch five tones, the feeling, the atmosphere, was totally changed. That is why music has such a strong psychological effect,”

For other films by Teshigahara, Takemitsu created completely different sounds. The boxing documentary José Torres was shot in New York in training gyms and boxing rings and on the streets of the city, and Takemitsu provided an appropriate urban jazz setting. For The Face of Another, he composed abstract sounds and Weill-like tunes. (Music from both these films appears on this recording in Takemitsu’s 1994 suite for string orchestra, Three Film Scores, combined with the elegiac funeral music from Black Rain, Shohei Imamura’s film about the Hiroshima bombing.) For Teshigahara’s historical film, Rikyu, Takemitsu’s sounds included darkly traditional strings, European baroque court music, and massive pedal points.

To Takemitsu, “timing is the most crucial element in film music: where to place the music, where to end it, how long or how short it should be.” In Masahiro Shinoda’s Banished Orin and in Nagisa Oshima’s Empire of Passion, both melodramas, Takemitsu used music sparingly and evocatively to underline the emotion and, at the same time, to suggest – as with the endlessly turning jinrikisha wheels in the Oshima picture – inevitabilities not to be found in the visuals. He was also capable of supporting the images in the most direct and unambiguous fashion, as in his bright score – all primary colors – for Kurosawa’s Dodes’kaden.

Despite the eclecticism of Takemitsu’s film music, his style (and its techniques) remains continuous. Noriko Ohtake in her 1993 study, The Creative Sources for the Music of Toru Takemitsu, identifies one technique which the composer calls (in a typically movie-like description) “pan-focus.” It consists of melodic fragments used as structural blocks, with placements of sound creating a many-layered color. This sound – what one might call Takemitsu’s elegiac mode – can be heard on this recording, for example, in the music for Rikyu and Black Rain, but it is a technique that occurs in many of his compositions for the concert hall as well.

Yet only in his film scores are Takemitsu’s concerns joined to the intentions of the director. The latter asks a question, as it were, and the composer answers it. He offers his directors a blank page of music and upon this he transcribes their mutual intentions. In doing so, Takemitsu shows as much diversity in his film scores as in his other music, while also exhibiting a similar unity in composition. ”