by Claire Bartoli

An attempt to assemble critical pieces approaching cinema “from the standpoint of sound”. This article was originally published in the booklet of the sound recording of Jean-Luc Godard’s Nouvelle Vague (ECM, 1997). Translation by John M. King.

In a first period

– the old testament –

a human being

(a man)

is rescued from ruin

by another human being

(a woman).

In a second period

– the new testament –

a human being

(a woman)

(the same)

is rescued from ruin

by another human being

(another man).

But the woman discovers that the other man

is the same as the first

that the second is

(still as before)

the same as the first.

So this is a revelation.

And if man proclaimed the mystery,

it is woman who revealed the secret.

I’ve listened to Nouvelle Vague, yes, the film Nouvelle Vague. I’ve heard it. I can’t see it.

Despite my blindness I go often to the cinema. It gives me a lot of pleasure and intrigues me. Naturally, I go for films without a strong visual emphasis, those that contain many dialogues. Assisted by someone who describes a few scenes or décor elements, I use my imagination. I could see up to the age of twenty-three; I have also retained many visual memories and thanks to my imagination, the colours and images replenish the present stock of my “internal cinema”. The films populate the space within, producing bubbles of visual perception or coloured emotions. Listening to a film is a pleasure, but it also means an effort, concentration … Evoking precise memories to render the interior world as rich as possible, imagining and inventing to bridge the silent gaps. There are some film sequences I am convinced I have seen “with my own eyes”, so powerful and clear is the impression left on me by their scenes and colours.

So, just as in everyday life where all my gestures and movements require constant vigilance, cinema also demands intense concentration if I don’t want to lose my thread.

I listened to the soundtrack several times, on my own, without knowing anything else about the film, then I recorded on my tape-recorder (the notebook that never leaves my side) my first impressions. It was in summer, in a little village in the Ariège, in the middle of the Pyrenees. I don’t take my braille material with me on my travels. Back home, I made another copy of these notes, the first outline for my work. Then, much later, I became immersed in listening to the film once again and had one of my reader assistants record the dialogues published in the L‘Avant- Scène Cinéma (no. 396-397).

Again I noted pell-mell my feelings and thoughts on my little recorder. I appreciate this mode of writing, as it is capable of keeping up with the rapid flow of thought. For this reason my writing occasionally bears the features of the spoken idiom, as it does here now.

I made another copy of these words in braille, rereading the whole to sift out five main subjects, a bit like the chapters of a book.

To achieve this aim, I used a cutting technique. I snipped away at the braille page with my scissors, cutting out, subject by subject, little scraps of paper that I then put together again when I thought they matched. I play with the scissors, but unlike Jean-Luc Godard, hardly by choice. Not having a braille computer yet, I use only a braille typewriter which does not allow me to make any corrections. I systematically recopy the whole page.

After this to-ing and fro-ing between my tape-recorder and the write-up in braille, a friend came to help me check certain dialogue excerpts in L’Avant-Scène. She was somewhat horrified to see me among all these pieces of paper littered all over the office. At that stage I wasn’t at all sure I would ever escape from it all.

The next day, my mind clear, everything sorted itself out in the editing. No story, no chronological order, no events. I could not, as I could with other films, accurately depict in my mind’s eye what the sounds evoked, I could not visualise them. What remained was a melody, a musical mosaic. I had navigated to the rhythm of the thinker: overlapping outlines of thought, on the surface or deeper down, like the waves of the sea.

Jean-Luc Godard said: “… my film, if you listen to the soundtrack without the images, will turn out even better.” I’ve started playing this game.

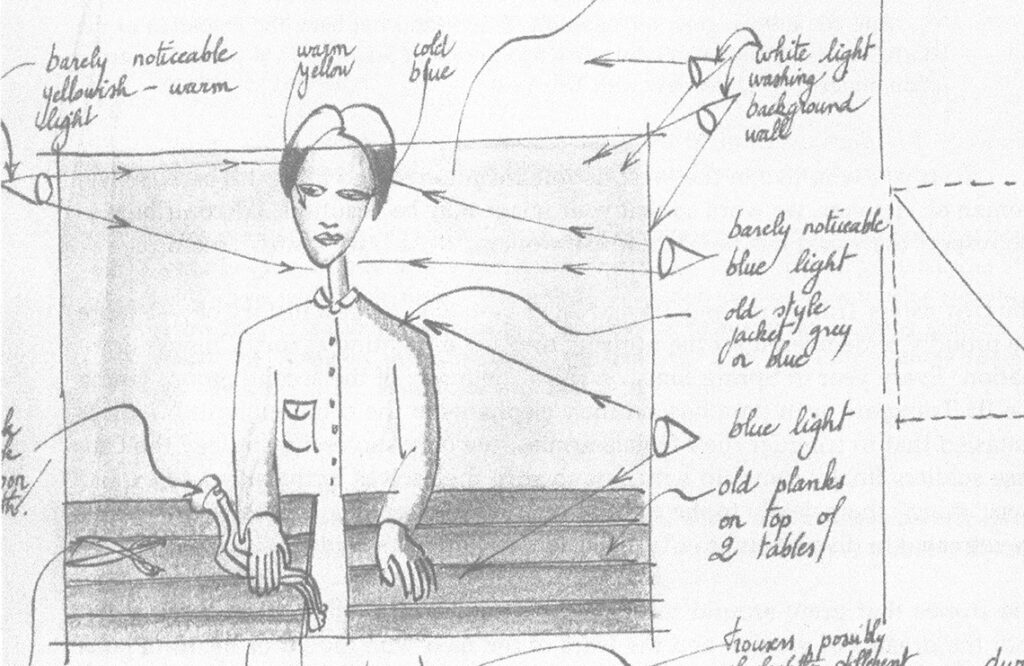

I conceived the layout myself: my own thoughts occupy the whole width of the page; the indentations are a textual description of the sounds as I perceived them (in small capitals), with my interpretation of these sounds; and in italics are the fragments of the film dialogues.

THE SOUND

First sensation: I can’t tell what is going on. The sound fails to reveal the action, just a few décor and movement elements.

Tell-tale sounds: steps on the paving, the stairs, the chimes of the clock …

Birds singing, crunching of gravel under car wheels, a horse whinnying, barking, sweeping of leaves, birds in the tree tops. The voices outside do not have the same tonality as those inside.

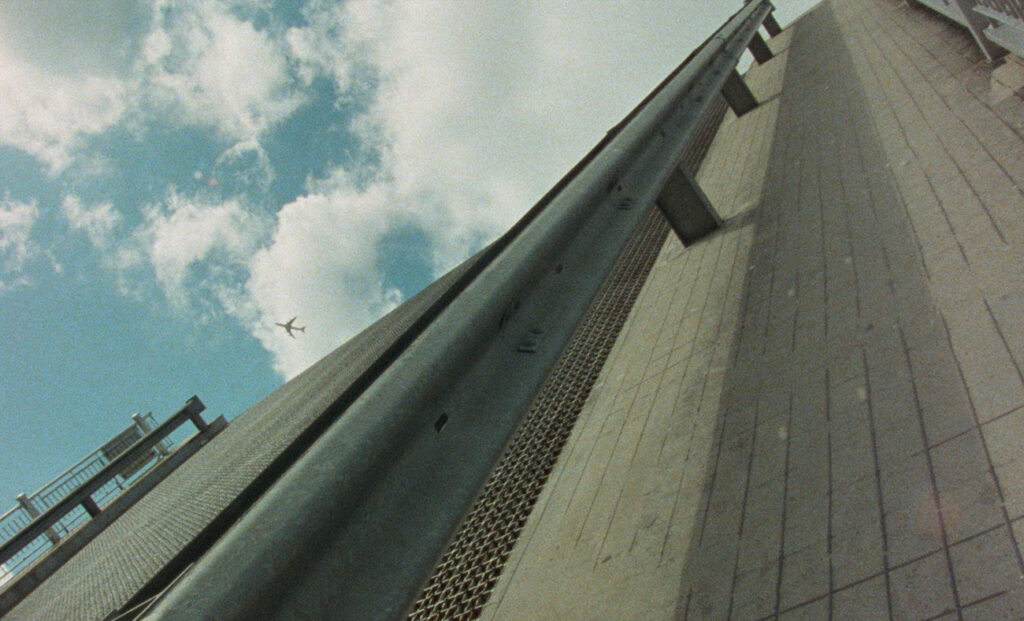

The jet engines of a plane. The resonance and fading out of the voices.

Grinding sounds, machines, wheels turning, mechanical hammering at a factory.

Elsewhere, a boat engine, a diver, swimming, pleasure and distress in the water of the lake. Then, other sounds: the waves, the thunder, the gulls do not indicate a location but are like the elements of a musical score, words among other words.

And then, a feeling of being lost: some things are said and I cannot hear them completely.

Amidst this fragmentation, the superimposition of all those words. I endeavour to follow one particular voice rather than another but fail. Slipping away, it eludes me.

Anything else to listen to … Yes, the relief of a landscape, composed of elements in successive layers, where words and sounds obscure and bump into each other, fusing together.

It’s a story I wanted to tell …

THE MUSIC GOES BACK AND FORTH BETWEEN THE WORDS. I should know by now that they are not there for their own sake, as Jean-Luc Godard plays the game of rediscovering them. A BIRD SINGING, A DOG BARKING, THE ENGINE OF A CAR STARTING THAT IS IMMEDIATELY CAUGHT UP IN THE MU SIC. ITS VOLUME INCREASES, REJOINING THAT OF THE CAR.

No place, no time for me, another reality, the metamorphosis of the universe of sound.

Godard, with large cuts of the scissors, divides the material into fragments, producing sound miniatures, as pure elements.

THEN COMES THE RUMBLING OF THE STORM, FOLLOWED BY THE NOISE OF A VACUUM CLEANER, SWEEPING, AND A MAN’S VOICE – There wasn’t enough time to discover, like a lamp that has just been switched on, the chestnut-trees in bloom.

My attention sharpens in an attempt to discover the faintest drop of sound: a beating of wings, the chimes of the clock, some snatches of a song, the trickling of water, nuggets deposited with the gentle care of a goldsmith or an alchemist.

STEPS ON THE PAVING, inside a house, THE VOICE CONTINUES, also inside. IT SPEAKS OF FRAGILITY. And everything one hears renders it fragile: THE RUSHING OF THE WOMAN AND THE SERVANTS, THE RINGING OF THE TELEPHONE… – things of our times that fill life and yet hollow it out, rendering it empty, void.

If Godard adjusts the sounds with the subtlety of a composer, creating shadows and sparks by rubbing them together, I deem him to be a magician capable of producing a bird from a hat, the individual elements being contained in each other.

THE DISTANT SOUNDS OF A CAR HORN ARE ENGENDERED IN THE MUSIC ITSELF, THE LATTER IS AMPLIFIED; SPEED, TOOTING, SLAMMING OF BRAKES. The fusion of the two elements generates the intensity of a perturbing, tragic sonorous event.

Interlude, A SONG BY PATTI SMITH, A more reassuring rhythm and beat in the closed metallic cage of a car. The words stop dead: You’re injured? Still at the side of the road: A BIRD SINGING, CARS PASSING … But what has happened? An accident, maybe?

Godard, the magician, the ferryman from another reality.

BEES BUZZING, a little grain of sound announcing Richard Lennox’s arrival.

Godard dislodges the sounds of the world, fashions them, isolates them from the life peculiar to them: a bark, a strain of music, a few words by a writer, the ring of a bell, the sound of waves returns to them their peculiarity; playing their significant roles of intervention, rupture, tragedy and mystery they become events. The emotion is engendered by the very substance of the sound.

THE NOISE OF A PLANE COMES OVER ME. THE RINGING OF THE PHONE, THE SHRILL CRIES OF THE BIRDS.

Nouvelle Vague invents concrete music that does not hew to the beat, that toys with the irrational. Can’t we tell that we are made from the fabric of dreams?

The uneasy dialogue between the financiers awaiting Richard Lennox’s arrival is interrupted by A SONG, THE TOOTING OF A CAR HORN, imparting a musical note and substance to the danger of the situation.

WHEELS TURNING, GRINDING, MACHINES, METALLIC HAMMERING …

And then the words … Ebbing and flowing, confusion and clarity fade and return between the various planes of sound. Passing words from amplified, then obscured voices interrupting each other, stammering, echoing in the panorama of sound.

No doubt a factory, a building site … EXCHANGES BETWEEN INDUSTRIALISTS IN CLEAR VOICES. They are discussing concrete problems. Other voices, deafened, say: Love, Creation …

Godard loves words, but he does not burden them with a concept, he hollows them to fill them with something else. They touch each other, ring, bounce back again, shatter into little pieces of useless glass, composing a score of notes, juxtaposed or bundled into chords.

Women are in love and men are alone.

A woman cannot do much harm to a man …

Love and attachment… attaché from an embassy … movement … movie … cinema.

In an appointed disorder words assume poetic substance. Separation and reconstitution: certain words are sucked down towards the depths, covered up again, then swell, thread their way along the surface, weaving from wave to wave.

Dorothy Parker: I’ve already told you there’s a price to pay when you’re good and when you’re bad. ELENA’S VOICE SUDDENLY LOUD AT THAT MOMENT: A memory … By virtue of its contact and intensity, the word then seems to respond to and reverberate with what has just been said.

THEN THE VOICE BECOMES INDISTINCT: … is the sole paradise we cannot be driven out of.

Richard Lennox: … catches up with the wave receding and falling back into clear water … a hell we are condemned to in complete innocence.

A PHRASE FROM RAOUL, AT FIRST SONOROUS: What she then discovers … – THEN ROLLING TOWARDS THE HORIZON: … is that her lover has committed the unforgivable mistake of being incapable of existence. – THEN RESURGING TO THE FORE: Leaving melancholy. Here is a rhythm, a space, far and near joining in harmony: oh, yes, melancholy.

The voices trumpet, penetrate the air, ring out. Small insertions of a noise, some notes, the object resounds. These cuts in the sound mark the beat or bring things to a halt.

THE RINGING OF THE PHONE ABRUPTLY INTERRUPTS THE SONG BY PAOLO CONTE AND THE DIALOGUES. CHORDS ON THE PIANO, DIVIDED AND INTERRUPTED WORDS FROM RAOUL, WAR-WHOOPS AND BIRD CALLS. EVERYTHING INCREASES IN VOLUME AT THE SAME TIME, THE BIRDS, THE “INDIAN”‘S CRY, INTENSIFYING… Too many words, derisory words! A single bird call could put a stop to everything.

Words are no longer words, the sounds of the world are no longer the sounds of the world. A new polyphony, magic.

People will say … A BIRD CALL MIXES IN WITH THE VOICE: It was the time when there were rich and poor, fortresses to be taken, ladders to be climbed, desirable things that were forbidden to preserve their attraction. Chance was one of the party. Nostalgic meditation? Author’s comments? THE NOISES CONTINUE TO JOIN IN, THE VOICES OF EVERYDAY LIFE. THE STORM THREATENS, BREAKS … because the world breaks. Danger. Only the birds and the dog hear the voice of the heavens.

Fragmentation and dispersion by means of which Godard drags us into a quest for desperately desired reconciliation between the earth and the heavens.

It is quite right that I should hear now and then the earth gently groaning, sending up a ray of light to rend the surface.

The more sombre and grave voices, such as Richard Lennox’s, seem to contain a little of this light. Others, distinct, loud, those of the merchants, freeze with their own emptiness. Behind Lennox’s firm words explaining the economic situation the gardener sweeps untiringly: the union of opposites, the fleeting and permanent nature of the seasons, modern times, the collapse of the old world?

A pleasure for the ears. Words losing their privilege. Certain noises mask them completely (the plane, the car, the machine), music also obliterates them.

Amongst the apparent calm of the conversations, business lunches, contract negotiations: under-cover terror. All profundity hammered by a contemporary world devoid of love.

Nostalgia that I feel palpitating between the bandoneon and the violoncello, in the faint or grave voice of the gardener,

A garden is never finished… but if it is abandoned …,

or in the deep one of the man, or of other characters that are simultaneously “I” and all the others, in multiplicity. I hear that nostalgia in the call of the bird rending the screen of useless words, with the savage force of an older world, or in the lapping of the waves bringing the sands their burden of memory and a new beginning. Nostalgia like the myth of a lost paradise. I think of Mircea Eliade: The life of modern man teems with half-forgotten myths… with obsolete symbols…

Godard reminds me of everything passing between “I” and the other that I am, between the others that approach me and what, of them, crosses my path. His predilection for disruptions and contrasts, these powerful relations he inserts between the words; the voices, the words and the sounds reveal (in a highly sensitive manner) the complexity of a conscience composed of literary reminiscences, of social, moral or aesthetic prejudice. The mystery of love, of a woman, the solitude of a man find themselves degraded, erased, relegated to the backdrop of a torrent of commonplace concerns.

Nostalgia and the dance of “all those images”.

What are all those images, sometimes free, sometimes confined … a tremendous thought?

Draft for another reality: the earnestness of life and the imbricated dreams, ephemeral and permanent states, melancholy and imagination. Will this modern man, cut off from the energies of nature that he only sees as a pleasant décor, stem the current, will he rediscover contact with the universe around him?

Beyond the realm of words, the music, expressed as the inexpressible fluid enchantment, returns like a memory, never to abandon us. It is also fragmented, inserting itself into the score of sound. And yet I feel its permanence, in slow waves.

THE FLUID TO-ING AND FRO-ING OF THE BANDONEON ACCOMPANIES THE FIRST PHRASES OF THE FILM – It’s a story I wanted to tell … and still want to … – giving way in some gaps to THE CALL OF A BIRD, A DISTANT STORM …

Shadowy and gently caressing, the music advances, as if predetermined. It lunges forward with the spoken words, charging them with intensity:

More generally speaking, a memory is the only hell … – THE MUSIC STOPS – … we are condemned to in complete innocence.

In accompaniment, the music may rise up at the same time as a cry.

THE SERVANT’S CRY.

It becomes finely engrained in the mosaic of the spoken word, fuses with it, anticipates it, punctuates it, interferes with it:

WITH THE ORGAN: Oh, how far toil is, how far the angels.

Alternatively: Tell him that you will really love him.

It harmonizes with the echoes of the interior dialogue.

In the second part, THE DIALOGUE BETWEEN HIM AND HER. He replies in a very concrete and superficial manner; suddenly an older phrase – The presence you have chosen accords no farewell. BRISK TREMOR FROM A VIOLONCELLO.

ACCELERATED RHYTHM just before they take the boat out onto the lake … Danger… Elena falls into the water, THE MUSIC BECOMES FRENZIED, HARSH TONES, PANIC … the imagination has a completely free rein. IT WAXES SOFT AND CHARMING AGAIN WITH ELENA’S WORDS IN ITALIAN. It caresses, becoming tender and comforting, nursing the wound. This interior sound opens doors, frees the emotion the neutrally spoken words do not reveal. The agitation between the words.

In its incessant equilibration it welcomes the moving, fluid force; it is accompanied by the words of the time, of the tangled time and new beginnings:

They felt big, immobile, with the past and the present above them like identical waves.

It can disguise comprehension or give it the beat, like the percussion.

Every transaction is sane – MUSIC – S.A.I.N.T. – MUSIC.

THE WORDS

The slightest word that would tell us where we are, where we are going would be of incomparable value.

What are they? All those words at liberty, shot like arrows that will never fall to the ground, fleeing, irretrievable, escaping from books or enclosed within them?

I am almost drowning, confusion… welcome this gushing chant of words, words punctuated to the point of becoming magic formulas. The solitude of words.

Are they replying to each other? These little phrases cast like bottles into the sea. Bygone words, blue words, sailing in deep water.

The love that seeks itself:

It is neither time nor lassitude that must be feared in love; it is the impression of security, a state of inadvertence. One forgets that this charming being is transitory, one hardly enjoys it like a summer that will return, allowing so many beautiful days to be lost.

Love is more than love.

The memory of the world:

All of them, outlined against the backdrop of the lush green of summer and the royal glow of autumn and the ruins of winter before spring blooms again … it’s not as if they were defending the living against the dead with their enormous, monolithic weights and masses, but more like the dead against the living; nay, protecting the empty, pulverised remains, the innocuous dust and without any defence against the anxiety and inhumanity of the human race.

The words immediately echo each other:

Roger Lennox: I will remember … the voice of the interior monologue: A memory is the sole paradise we cannot be driven out of.

The Chairman: In any case, he can’t be any worse than the other one.

Raoul: But in that case there is a way to do it, and a way not to.

Little pebbles falling into the water disturb the surface, in ripples far and near.

Leaving melancholy …

Before we met, we were already unfaithful to each other.

The summer echoes itself in the gardener’s lyrical and grave words. Distant waves surfacing at another time of the film.

Summer is early this year and a little wild …

Like that pile of leaves burnt by the summer …

Perhaps it’s the famine that is ripening in this summer heat and almond fragrances.

Echoed notes resound in the heart of the other.

Lennox: The presence you have chosen accords no farewell.

Elena: Accords no farewell. -The regret…of having paid too high a price for a profit of some kind.

Lennox: Of some kind.

Here the words bounce upon the skin of an imaginary drum. A deaf, subterranean word submerged by the shouts of the merchants makes us wish we could hear better. A plethora of foaming, noisy, gentle or fallacious little phrases. A pro- fusion of puppet-like words.

In this chaotic polyphony I perceive the breathing of nature, springing forth in bird calls and whinnies. Which ear is meant for hearing the movement of the water? The silence of the words would be necessary.

Godard weaves a thread of continuity between the world’s memory and man’s.

All that grass there, is it within me? Is it grass when it is without me? And if no one gives it a name, what is grass when it is … nameless?

In this world built on the values of money and production I feel a constant fragility; the rumbling of the storm and the call of the bird pierce the screen of words.

Summer was early this year, everything came into flower at the same time, the white lilac, the cherry trees …

Here, even a fine summer evening made us feel our fragility.

To whom is the solitude of the word addressed? Roughly-hewn words, cast without any outcome or origin, like the objects of our day and age thrown away after hardly any use. Solitude in the uproar of the silence of the others.

You talk, you talk… How could you understand that there are others?

I say “me” but I could say a man, any man.

This man in possession of knowledge, in possession of progress exercises an influence on the whole world, and yet he is alone, lost, exiled in himself.

You haven’t understood anything about my silence.

But there is no silence: the sonorous landscape is teeming with a thousand sounds and words. Man’s silence is inside the sound; it is necessary to search for it in the slowness, the distance, the space that disturbs the word.

Roger Lennox’s words, their emotion, laboriously clear the way towards the outside.

How could you understand that there are others, others who exist, who think, who suffer, who live? You only think of yourself.

In this mass of auditory impressions, I divine the opacity of the secret.

We have been given the positive, it is our responsibility to create the negative.

A garden is never finished… but if it is abandoned …

The fervour:

The miracle of our empty hands …

love is more than love.

The spark of life:

It’s still winter but rather tender gleams lend the mist an iridescent quality, in the evening a grey cloud is fringed with fire, a sign of light, the discreet annunciation which will be forgotten in the rains and deceptions of March.

The light twinkles, eternal, once it has passed beyond the individual and time.

The words travel through a landscape in full relief and perspective. Godard mingles the dialogues with internal thought.

Your face…

He: What face?

She: I can’t see you.

He: Look at me …

And then, the other one in him:

There is never anything else in my being but all the words that will re- vive me…

The presence you have chosen accords no farewell.

Slight variations in intonation permit distinction between what is expressed and what is restrained.

She thinks: It’s us against all the others… I had to do what I did.

She says at the same time: You mustn’t worry for my sake.

The clarity and the obscurity of the secret. The man before in the depths of the heart of the man after. Does Godard want to lose us in the interior monologue by mixing all the times and the silences of the time, by spouting it from almost all the mouths of one who is in fact the other? Who is pursuing whom, to which fate?

Polyphony of voices interrupted by those of everyday life: a jumble of material concerns, a flashing of ephemeral thoughts. Incessant effervescence of thought. Everyone follows the trajectory of a little solitary planet. We are travelling between different levels of consciousness, perhaps.

IN THE DISTANCE, A TENDER ATTENDANT VOICE: Women are in love and men are alone.

A woman you love deprives you of other women and sometimes of love.

HARDLY AUDIBLE: … the extent to which you have been alone all your life you cannot imagine …

Jean-Luc Godard loves words. He jubilantly hunts them down in books, he shakes them about like a puppeteer, knotting and unknotting their thin invisible strings from one quotation to the next. A servant quotes Schiller:

Friends, what a pleasure to serve you. But what I do stems from a sincere disposition, thus I reap no credit and am deeply distressed. What may I do? I must learn to hate you, and, my heart full of loathing, to serve you, since this is my duty.

Her brother: Is it possible that one should say “women”, “children”, “boys” without having suspected that these words, for a long time, have not had any plural, but only an infinite number of singulars.

The permanent feeling there is another self. Everyone can be the commentator on what is happening to him.

He: They had the impression of having already experienced all that …

And everyone in turn contributes his thread of the warp to the weft produced by the meditation of Godard.

The gardener: One always learns something from the imbeciles lost in a drama.

D. Parker: Men organise the mystery and women find the secret.

Raoul: What women then discover is that their lover has committed the unforgivable mistake of being incapable of existence.

The mosaic of our existence, a fragment of all the others.

R. Lennox: Whatever I say, there is never anything else in my being but all the words that will revive me.

Raoul: She does not suspect the extent to which she is sometimes surrounded; even when she thinks she is alone with her lover there are many people there with them, her lovers former and future …

Abrupt cuts, haunting repetitions, incantations between the earth and the heavens.

SHE AND HE

She and he meet, and love travels like a question. To what extent do they meet each other?

What a miracle it is to be able to give what one doesn’t have …

Love does not possess, it’s the face of the shadow of the world of possession.

It rows across their voices,

HERS ROUGH AND GRAVE: HIS DEEP AND SOMBRE.

She and he reply to each other in the filigree of a tangled web surfacing and submerging… waves …

MELANCHOLIC MUSIC FROM THE BANDONEON. SOFT VOICES, MURMURING.

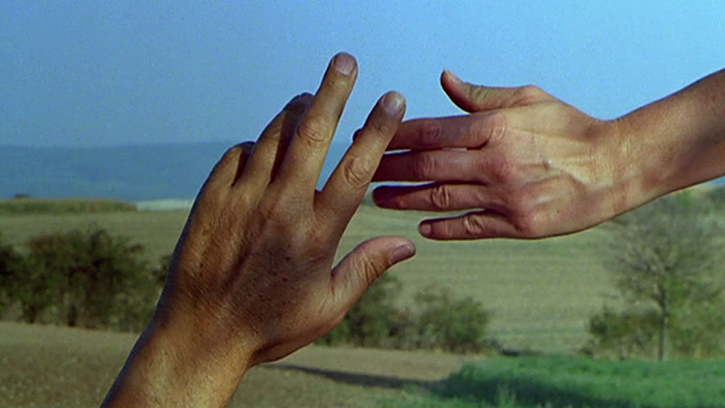

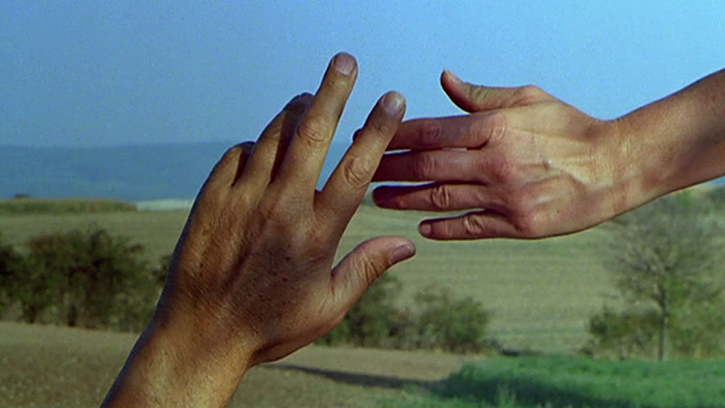

Intimate spaces are near at hand. His badly shaven face, his hands that she kisses …

My love, my love … it’s of little importance that I was born, you are becoming visible where I have disappeared.

THE DOG BARKS. Perhaps a link with the outside world? One is never alone with one’s love.

I will work as long as the day.

THE CLOCK STRIKES. The objects echo the words. MELANCHOLIC MUSIC MINGLED WITH THE WAVES AND BIRD CALLS.

He: Amidst the promises of our love … before we met, we were already unfaithful to each other.

The “promises” and the “before”, inseparable, like the wave and the gull. Waves of things said and done with that will always return, and promises of love like the beating of wings.

HIS VOICE HAS BECOME DISTANT, vague. Elena’s words, deaf, hardly cross her lips: Let us clasp in our hands, so to speak, this happiness now begun …

Her warm and mysterious voice closes the space between the hands touching each other. The gull flies towards the horizon … The love they devise for each other …

MURMURING. Thank you for accepting …

He restores the distance. BUT THEN HIS VOICE VIBRATES A LITTLE DIFFERENTLY, becoming more sensual: Say no more.

I say to myself: one of the voices is his speech, the other his thought. And all lapse into music again.

THE BANDONEON CONTINUES, THEN STOPS.

Say no more.

WORDS, INSTRUMENTS, WAVES, THE CHIMES OF THE CLOCK, MURMURING…

For me it’s a dance, soft, drawn out, sorrowful, too. Retreating and returning, from one to the other.

A point on the horizon in the sound panorama, the dialogue proceeds at its own slower rhythm, like the ripening of a fruit…

She: The miracle of our empty hands…

He: My mother used to say to me: giving a hand to someone was always what I expected of joy.

The hands always reappear, testimonies to a bond of love, all charged with what their words will fail to say.

Let us take into our hands this happiness now begun …

The sensual presence of their love. The words do not fragment it, do not hollow it out. Hands extended to each other, given or not given.

On the lake: Give me your hand …

The one that is not taken, the one that brings death.

WHEELS TURNING, ELECTRIC SAW, METAL HAMMERING, undoubtedly a factory, a building site? IN THE IMBROGLIO OF THE BUSINESSMEN’S VOICES, POWERFUL, SELF-ASSURED, ROGER LENNOX’S VOICE, ALMOST DROWNED, seems out of gear, being genuine.

What are you up to here?

Arousing pity.

His profound words do not reach the surface of the discussions.

She alone hears them and REPLIES IN ITALIAN, only for his ears:

Five more minutes and we’ll be together again.

Amidst these illusions of exchanges, as revealed by the decoupage and the superimposition of the dialogues, she and he answer each other, in a thin, unobtrusive voice. Privileged moments in a labyrinth of solitary paths. She occasionally soft, a wave touching the deep ocean of his solitude. Almost at the same time she slips onto the sand of futile investments.

“Rimorso” regret …

He doesn’t just reply to her, he takes up her thought and interprets it. This is real listening.

… the feeling of having paid too high a price for a profit of some kind.

He continues:

of some kind – a heartfelt echo.

This man of silence, withdrawn into himself, replies to the others,

IN A HUMBLE, VACANT VOICE: I arouse pity.

With Elena, IN AN EMOTIONAL VOICE:

She: It would be nice if you said something.

He: I know, but I always wonder what.

Their words are coupled with other vibrations: THE RUMBLING STORM, THE WHINNYING OF THE HORSE.

Two sides – two worlds in confrontation: the intimate and the everyday, the exterior and the interior, the severed moments of two individuals.

He, simple and humble: Your dirty money…

She, her voice stifled, colliding with his own. Firm, self-assured, business-like: It could be yours as well.

Then it is he who becomes implacable.

He answers everything with a blanket of words.

She: I think that love has made me blind… I can’t see you.

He: But look at me!

The man before is wrapped up in himself.

On the lake again. AMOROUS MELODY IN ELENA’S VOICE. DOUBLE, INTERLACED VOICE: I love you… it’s us against all the others.

The stories are revived.

With the same harshness he says:

Kiss me, as if she had said: Give me your hand.

Interplay of voices, of multiple persons, restrained, caressing. This cinema makes me hear the invisible, the connection, the border between what is neither one nor the other, what separates them and pulls them towards each other. I sense the imperceptible margin between the words and the persons, the indecipherable element, the transparent knot between the threads of their destinies.

DIVISION OR UNITY

The disassociation of the visual and the sound elements: each sound existing in its own right in a very indirect liaison with the image. Two impervious worlds? Not quite. Imperceptible links, beyond all logic. So I toy with the sounds, fractured and stuck together again, creating my own pictures. This is the artist’s present: allowing myself to leave an illusory reality to re-enter that of the imagination. What one sees is not what one hears, what one hears is not what one sees. I cannot divine a person’s physical appearance on the basis of a voice, but it provides me with a more interior, less regulated truth.

At first the unity seems to burst into pieces subject to the fragmentary and dispersive action of Godard. He fragments sounds and words, interrupts, contrasts, creates distances, superimposes. I immerge into this strange movement between the right and the wrong side of the words, into the incomplete phrases that never cease to elude. The outside world, everyday life, the superficial words cross the interior world, in splinters, fragments or deep waves.

A work of demolition, and the nostalgia, perhaps, of a lost unity. The words of an old domain regularly lap onto the shore.

Before we met …

A memory is the sole paradise …

It was the time when there were still rich and poor, fortresses to be taken …

A melancholic embrace, the energy of the fragmented words is broken by a moving slow pace, where the vagabond characters of this tangled time meet and pass each other by. The drawn-out interior dialogue, violently broken by the noises from the outside (machines, engines, the telephone, voices …), redistributed in the speech of one or the other, is a deep current that fades and is then reborn: a thread in the weft of an iridescent material. The unity of man fades with it, the unity of the world, and here the magic bond between them quivers. I feel the power and the originality of this film in the gentle touches of the chosen elements, the harmonious or dissonant encounters between the notes, the transparent threads between the things and the people, the caresses, touches and clashes.

Just as Jean-Luc Godard loves to divide, he also displays the power to reunite.

Memories… they return to become – inside us – blood, looks, gestures; when they no longer have names, no longer differ from ourselves, only then can it come about, at an extremely rare hour, from their midst, that …

I listen. A feeling of dispersion, of flight, oppresses me a little, then I taste this alchemical concoction. Its unity is recomposed for me by the emotion. Opposites are no longer opposites, as they beget each other like reflected reflections.

TIME

I listen. Neither time or space, but an intermingling of all time and all space. Words of the present, the past, thoughts of all times. The man after, the man before, no endings, only new beginnings. Little waves in a large sea, unfolding and subsiding: it’s the same water, but not the same wave. Godard juxtaposes moments, creating another time where past and future are contained in each moment.

Time seen via the image is a time out of sight. The individual and time are quite different. Light twinkles, eternal once it has passed the individual and time.

Losing my sight made me feel that the eye projects towards the outside. The ear takes us back into our interior world. Time is both inside us and outside us. That’s what Nouvelle Vague reminds me of in its interlacing of moments, memories, seeds for the future, where it is the interior being that re-assembles the scattered moments of life. Robert Pinget describes Monsieur Songe’s reflections: ... the minor events of his existence that have no connections between them or, better, incommensurate connections, or that occur all together or that he has already experienced and that recur relentlessly.

The individual that seeks or finds itself in itself does not experience continuous, progressive time, but fragmented, divided time. Lo and behold, there is no evening after day, no morning after night, but what exists is a splintered, fragmented line of slow or flashing moments, parallel or broken, without any outcome. The continuance is not that of the action with its first fruit and consequences. The factory scene occurs just after the meeting between Elena and Lennox.

INTERIOR, EXTERIOR SOUNDS, OF LEAVING AND RETURNING. Which time transpires between all these moments?

The time lags behind, assuming a different rhythm. It leaves the path of linear progression, opting for the escapades of brief eternities. Jean-Luc Godard hurls these little fragments of time up into the air, maybe to find out the sound they would make when falling. And yet it is not a game of chance, but the composition of a score, in flashes, showers of moments, in series, in multiplicity. In the movements of the stars, those of nature, there is no more regularity than in ourselves.

The society we have lived through may be considered to be defunct …

If it is recalled in future centuries, it will be thought of as a charming moment in man’s history, people will say …

He stops. The thought processes re- quire time to mature. Society has realised this and that’s why it spares no effort to glorify love. It’s a key to productivity.

Pauses and sighs in the score, but no gap. A profusion of memories that do not have the time to burst to the surface, of unsatiated desires … and the present pounds away at it all. In the foreground, men reduced to insects, devoured by utilitarian time, historical time. They live according to the rhythm of the fluctuations of the dollar rate; for them nothing exists outside that time.

But Godard resists this belief in the reality of this time, opening up the horizons of the “grand temps”.

Elena says, vehemently: It would be nice if you said something for a change.

I perceive the distances in the interior dialogue …

Much later, he says: I have no need to say anything, I help her just the same, she recognises it, besides, sometimes she returns to the midst of the people … Sometimes she doesn’t …

Godard arranges the sound material, he gives it its rhythm. Neither a classic progression nor a traditional series of sounds that would reveal the length and the effects of an action. Incidentally, this explains why I cannot divine any part of the action or the image solely with the power of hearing. I find myself in a revolving time where events are resuscitated, like the lake scene.

The presence you have chosen accords no farewell … A memory is the sole paradise we cannot be driven

out of.

The voyager through this time constantly comes across the signs of the morrow.

The incongruous words of the chauffeur – Have you ever been stung by a dead bee? – assume the message of urgency and prediction: A woman cannot do much harm to a man, she can disturb him, annoy him or kill him, that’s all.

The past breaks through in the voice of one or the other, a distant wave from the same ocean.

Is it possible for us to believe that we have to catch up on what has happened before we are born?

A memory is the only hell we are condemned to in complete innocence.

In the passage of time a man mentions the summer of flowers, ripe fruit and almond fragrance … a wild summer. Untiringly he sweeps the leaves of the summer coming to an end. I hear him and associate him with the permanence of the waves. All of this story could germinate and ripen in that summer. The gardener unfolds the seasons, timeless words, almost a legend, an old round dance whose steps have been forgotten. The gardener returns to the subject of summer at the end of the film. Has a year passed or has the meaning of the dance been altered? The music is inscribed in the passage of time. Melancholic, it comes and goes, unable to keep silent, it unfurls and then retires. Creating movement and permanence.

These signs of light will be forgotten in the rain and the deceptions of March.

I hear the light. The music bears it, many other noises also contain it: the bird song, the wind, the water, the heart of the world. The heart of man.

***

A composer … a poet … Godard dices the sounds, the words, their echoes. A hollow world becomes populated with words seeking, eluding, finding each other.

Jostled along the paths of my listening, I am thrown off course. He identifies the opposite poles; acknowledges them in our reality but clashes them so violently that we pass beyond these polar tensions to rediscover unity.

He blends lucid analyses of behavioural patterns (his own and others’) with compassion, words of love, violence and the harshness of business and moralising talks; rough contours, unexpected landscapes…

As in a novel, Jean-Luc Godard borrows several idioms: that of a class, a professional group, common, anonymous and everyday language or that of a certain character. They combine to form the speech of the author, who strides through every one of them, observing his own visions.

A man lost in himself, lost for the others, women in love, men alone… Their shadows come together, come apart in a world of no certainties.

An intriguing roundabout of complex and composite beings, masks and silhouettes; their existence seems stronger in the shadow than in full light:

Distant, deafened voices express more about the essence than strong, clear ones.

and the shadow of a single poplar behind me is sufficient for me, in its mourning.

The gravitation of all these travelling beings: the being one welcomes in one- self, for reasons of love, the other within oneself, the voices of shadow and sea depths, all the marionettes of modernity, stirred by the slightest breath.

All those voices… I have developed a strong liking for them. Each one has its own colour, its own accent, its own consistency.

I ran after each of them, in every direction. I could not keep hold of all the strings of those kite-words slipping into space. With Jean-Luc Godard one must accept losing. He does not supply us with things in their entirety but merely embers and wisps of smoke.

The error was wanting to hear everything in order to understand everything. The path he proposes is rather to hear the “entirety”. All those pulverised voices compose another one for me now, one alone, a human voice, fragmented but alive, spinning tales, containing gyrating atoms of the same cell, planets of the same cosmos.

What are all those images, …

That tremendous thought…

Cinema, eye and ear, observer of an outside world, reaps little pieces of reality… this deconstruction, symphony and distillation … to release a new reality of images, his, mine, multiplying endlessly.

… The thought, powerful and migratory, stemming from a distant exterior, the thought yet to be born, explorer of the unthinkable.

The voices outside are ferrymen: voices of the frothing waves, a passing fancy or straw fire, cymbals and frosted mirrors, those inside: immersed, grave, wrapped in a cocoon of flesh, a subterranean fire… And my listening is intent on pursuing the movement of the mantree rooted in the depths and reaching up to the skies.

But the character cherished by Godard may be that new wave, the water abolishing the form to produce it anew. The door is open but no-one has the keys, neither the characters nor the author. He has deposited in a corner of my ear an area of mystery which delights me.

The film – once listened to, dreamt of, reinvented – leaves me with a little subversive taste of the invisible and the eternal.