In the context of Courtisane Festival 2023 (Gent, 29 March – 2 April 2023) with the support of KASK & Conservatory / School of Arts. Curated by Stoffel Debuysere in the context of the KASK research project Echoes of Dissent.

The title of this programme, The Murmur of the World, is taken from a piece of writing that critic Serge Daney devoted to Robert Kramer’s Route One/USA (1989). In this film fleuve, Kramer, together with companion and alter-ego Doc, makes a journey from the beginning of Route 1 in Maine to its end in Florida. Along the way, numerous spaces and encounters unfold, combining to form a previously unseen and unheard of picture of the US. In many ways, it is both a sequel to and counter-image of a film Kramer made more than a decade earlier: Milestones (1975). In this vast mosaic of a movie, he took stock of the political radicalism that had spread from the late 1960s onwards in the US and far beyond. With this film, he closed a period whose portrait he had drawn like no other. A disillusioned Kramer then headed to Europe where he found a new base. One need not be a Freudian to see that sooner or later he would return to his starting point.

“Route One/USA,” he said, “comes from a conscious decision to return to the scene of the crime. The interesting thing about this film is that in Milestones, we crossed the entire country without ever talking to anyone who was not part of our crew. Route One/USA was the exact opposite: we were there just to talk, listen and learn.” Serge Daney continued on that élan in his piece: what does a doctor traveling across the hinterland do, he asked. He uses his eyes and takes from his briefcase that old emblem, the stethoscope. He measures up the state of the populations, he takes their pulse. From the people he meets and listens to, along Route One, he expects no truth: he simply follows them through a phase of their existence. He diverts them slightly from their route, as if offering them a free consultation. He does not dramatise the road (it is the opposite of a road movie in that sense), nor the encounter: these people are always there and have other things to do. He feasts his eyes but doesn’t expect anything from them – and that’s exceptional – a voyeuristic added value. Above all, he puts his ear to the ground. Here, cinema par excellence functions as a social and political stethoscope that measures the pulsation of hearts and ideas and lets the murmur of the world, in all its diversity, be heard.

Twenty years later, another filmmaker, Tariq Teguia, measured up the state of his native land. In Gabbla (Inland, 2008), the main character is not a doctor but a topographer returning to the Algerian interior. This choice is no accident: the work of the surveyor – going into the field, looking through a lens, drawing lines – is reminiscent of that of a filmmaker. It also evokes a certain philosophical practice: in a famous text, Gilles Deleuze described Michel Foucault’s work as that of a novel cartographer. Teguia, whose film practice is indeed that of a cartographer, once wrote a master’s thesis on Foucault. Moreover, he devoted a PhD to Robert Frank – whose photo collection The Americans could be seen as a precursor to Route One/USA – under the title Fictions cartographiques. Fiction implies a certain idea of displacement, and it is indeed displacement that the film Gabbla applies to a territory – that of Algeria – which consists in undoing its dominant configuration and confronting, through image and sound, a multiplicity of Algerians. Beyond the official scenarios about the ‘Third World’ and ‘growth countries’, about neo-colonialism, Islamism, liberalism and globalisation, the film, through a form of aesthetic hospitality, inventories and collects different possibilities of life that give new visibility and audibility to the community.

This programme offers a selection of cartographic fictions in which a concatenation of recordings and encounters does not reveal an ultimate truth, but constitutes a possible constellation, as an exercise in togetherness in difference. Fictions that accommodate a multiplicity of voices, languages, geographical and sonic territories, and, as one of the characters in Gabbla suggests, make different islands into an archipelago, taking all the possibilities of life inherent in each to their utmost eloquence.

——

Thanks to Nina Devroome, Kristofer Woods, Elizabeth Dexter, Céline Paini (Les Films D’Ici), Noshka van der Lely, Leenke Ripmeester (EYE), Helke Misselwitz, Mirko Wiermann (DEFA-Filmverleih), Céline Brouwez (CINEMATEK), Louise Richars (mk2), Tariq Teguia, Annabel Thomas (ECLECTIC).

Cues taken from Serge Daney, La Rumeur du monde (1989) and Jacques Rancière, Inland (2011). This selection of cartographic fictions is, of course, not exhaustive. One could also think of Gallivant (Andrew Kötting, 1996), Vers la mer (Annik Leroy, 1999), Rostov-Luanda (Abderrahmane Sissak, 1998), Les Glaneurs et la Glaneuse (Agnès Varda, 2000) or Michel Khleifi and Eyal Sivan’s Route 181 (2003), to name a few.

Route One/USA

Robert Kramer, UK, FR, IT, 1989, DCP, 255′

English spoken

Digitized and restored by Les Film D’Ici with the support of the Centre National du Cinema (CNC)

In September 1987, Robert Kramer returned to the US after a decade of self-imposed exile, where he spent five months filming along Route One, which connects Canada to Key West in Florida. In 1936, it was the most travelled route in the world, meanwhile it runs alongside superhighways and through suburbs – a thin strip of tarmac that cuts through all the old dreams of a nation. Together with fellow traveller Doc (Paul McIsaac), Kramer enters a succession of private worlds that steadily reveal themselves to the camera: from a Native American reservation in Maine to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington DC, from a Thanksgiving dinner at a homeless shelter to a sermon at an evangelical church. The grittiness of Kramer’s earlier militant work has given way to a casual mise en scène, with a fluid camera moving amidst ever-changing characters. Rarely did a filmmaker so fearlessly tread the fault lines between documentary and fiction, between inside and outside, to the point where the film almost breaks in half.

“I had met someone who told me about Route One, and that it was a good way to cross America. From that conversation, with nothing but a map, I wrote a two or three page proposal about a trip along Route One. Without any idea of what kind of film it might be, just the desire to move. Little by little, the project began to take shape. There was still no concept. I’m not sure I even thought I was going to make the film. There was the idea that we always fall back on: that of living a situation… During five months shooting along this route, I did not have the impression of filming the past, but rather of revealing the present. From the shadows of the interchanges, the town centers of glass and steel stand out against the horizon like studio décors. We were in the present, affronting difficult times.“

In the presence of Daniel Deshays

De weg naar het zuiden (The Way South)

Johan van der Keuken, NL, 1981, 16mm, 143′

English subtitles

Conservation copy courtesy of EYE

The account of a journey starting in Amsterdam on 30 April 1980 – the coronation of a new queen, the occupation of an office building, a clash with the establishment – and ending up in Egypt via Paris, southern France, the Alps, Rome and Calabria. A “road movie”, says Johan Van der Keuken, “except that the road surface has mostly been rolled up by the wheels of a car or a plane and taken along to the next stop, so that one is moving by fits and starts. Once you are here, then there – and what is between here and there is up to you to fill in: the inner journey, the route you plot out for yourself. In his characteristic intuitive and engaged style, van der Keuken encounters people trying to make a place for themselves: squatters, travellers from country to city, from South to North. An account of outward emigration and inner alienation, but also of resilience and life’s courage. A journey to the South that gradually makes one feel what it means to lose the North.

“It is a story of outer emigration and inner alienation, but also a series of signs of the courage to face life. It is the obsession with rooms, streets, places where people try to communicate their lives to other people and fight their battles against the injustice of the world. The film is long, two hours and twenty-five minutes, but it has to be this long to enable me to record the impressions of a dream voyage and to register changes in perception and style. I had in mind the creation of a composition that would be balanced and yet, at the same time, take shape spontaneously. One often walks on the border of arbitrariness: everyone has something to say.”

Winter Adé (After Winter Comes Spring)

Helke Misselwitz, DE, 1988, DCP, 116′

German spoken, English subtitles

Digitized and restored by DEFA

In 1987, shortly before the collapse of the GDR, Helke Misselwitz travelled by train from her home near Zwickau in the south to the north coast of East Germany. Along the way, she met women of different ages and backgrounds, whom she filmed with rare tenderness and precision. “For almost forty years, the law has established that women are legally and economically equal to men,” Misselwitz said. “But what has happened in those 40 years in people’s behaviour towards one another? That’s what interested me.” Referring to her own biography – she was born in front of a closed railway crossing – the filmmaker explores how women and girls live in “real existing socialism” and “how they want to live”. The women – two young punks, a worker in a briquette factory, a Berlin economist, and an 85-year-old woman celebrating her diamond wedding anniversary – tell of their disappointments, desires and hopes. Never before had anyone in the GDR appeared so openly and at the same time so naturally in front of the camera to talk about their circumstances and dreams. With the programmatic title “Farewell Winter”, the film marked the untenability of the official stance. It pointed to a clear shift in the mood in East Germany, which finally broke out a year later.

“The three structural elements in Winter Adé are the railroad journey, the intensive meetings with women, and the observation of daily life. The only fixed aspects of the film was that it begins with my birthplace in Zwickau and ends on a ferry on the sea. I definitely wanted to tell about myself in the beginning: by accident, I was born on the road, in an ambulance, right in front of a closed railway gate. And this fact leads into the concept of a railway journey. Of course, the railroad is a very important means of transportation in the GDR, but its meaning as a poetic symbol is also clear. It points to the existence of closed borders and also to the internal structure [of the country]: there are many tracks in life, but generally you can’t depart from the one you’re on because the switches are operated by someone else.”

Followed by a conversation with Helke Misselwitz

D’Est (From the East)

Chantal Akerman, BE, FR, 1993, DCP, 107′

Newly digitized and restored by CINEMATEK

Between 1991 and 1993, just after the fall of the Berlin Wall, Chantal Akerman travelled through Central and Eastern Europe – to East Germany in the spring, to Poland and Ukraine in the summer, and on to Moscow in the winter. “For already 20 years, I wanted to go to Eastern Europe,” said Akerman, “to work with Slavic languages, which are different but sound quite similar. I wanted to make a work about the changes in voices and languages.” However, the film developed, intuitively, into a completely different form: while the texture of the soundtrack is very important in D’Est, not a single word features in the film. Instead, an audiovisual composition of haunting impressions unfolds, without commentary, dialogue or subtitles. In a succession of long takes, a world in suspension, on the verge of an indefinite future, is revealed. “Without getting too sentimental,” she says, “I would say that there are still faces that offer themselves, occasionally effacing a feeling of loss, of a world poised on the edge of an abyss, which sometimes take hold of you, as you cross “the East” as I have just done.”

“I originally wanted to work with a lot of languages. I had a lot of preconceived ideas, but it was through traveling a lot in those countries and finding things that interested me both in an emotional way and in a cinematic way that the film took shape. We made four trips. We were shooting a bit, but I knew the film was not there yet. So through the traveling I saw these people waiting and waiting and I thought that I should install myself next to them and that would be the film. So the shape was in my mind, but it was still very loose. And then I shot the material and through the editing I started to find the shape. I started to swim. And, in a way, that’s much more interesting than to just follow a story. It’s through cinema that you find the cinema.”

Followed by a conversation with Pierre Mertens. He is one of the most respected sound recordists and sound directors in Belgium, who worked with esteemed filmmakers such as Thierry Michel, Claudio Pazienza, Bruno Dumont, Agnès Varda, and Elia Suleiman. He worked on several films with Chantal Akerman, notably De l’autre coté, D’Est, and La folie Almayer.

Zendegi va digar hich (And Life Goes On)

Abbas Kiarostami, IR, 1992, DCP, 95′

Persian spoken, English subtitles

Digitized and restored by mk2 films

In June 1990, an earthquake of catastrophic proportions struck Northern Iran, killing tens of thousands of people and causing untold damage. After the disaster, Abbas Kiarostami and his son decided to travel from Tehran to the area around Koker, a village where he made Where Is the Friend’s House? four years earlier, in search of the two child actors who starred in the film. The events of the trip and the story of a young man Kiarostami met along the way, who got married immediately after the disaster, stayed with him, and he decided to return to make a film there. In the fictionalised account of Kiarostami’s journey, as father and son move further into the countryside, the purpose of their mission fades and gives way to a sense of hope amid the rubble. When the locals refused to wear dirty clothes for the re-enactments and instead showed up in their finest attire, Kiarostami replied, “Why not? We are not portraying reality; we are making a film.”

“My concern was to find out the fate of the two young actors who played in the film but I failed to locate them. However, there was so much else to see… I was observing the efforts of people trying to rebuild their lives in spite of their material and emotional suffering. The enthusiasm for life that I was witnessing gradually changed my perspective. The tragedy of death and destruction grew paler and paler. Towards the end of the trip, I became less and less obsessed by the two boys. What was certain was this: more than 50,000 people had died, some of whom could have been boys of the same age as the two who acted in my films. Therefore, I needed a stronger motivation to go on with the trip. Finally, I felt that perhaps it was more important to help the survivors who bore no recognizable faces, but were making every effort to start a new life for themselves under very difficult conditions and in the midst of an environment of natural beauty that was going on with its old ways as if nothing had happened. Such is life, it seemed to tell them, go on, seize the days.”

Gabbla (Inland)

Tariq Teguia, DZ, FR, 2008, DCP, 138′

Arab-Algerian spoken, English subtitles

To the challenge of “Algeria documenting itself ”, Tariq Teguia offers an answer in the form of a road movie that turns its back on the city and goes deep into the hinterland. It is the story of a surveyor moving through the steppes of Algeria’s Saïda province, forging new encounters and relations. But it is also an assemblage of lines, colours, rhythms and sounds in which the desert functions not so much as a mythological space, but rather as an intersection of divergent lines of circulation that fleetingly converge only to diverge again: those of the fictional characters, but also those of itinerant workers, those of underground activists, those of illegal immigrants, those of different languages and musical forms. Teguia maps the territory and the different ways it can be inhabited as an amalgamation of intersecting lines, thus testifying to the complexity and heterogeneity that characterises a society. He weaves the lines not to make a pleasing tapestry, but to “see between the stitches”, to reveal the traces of the past and the signs of another possible Algeria.

“My way of proceeding is territorial, spatial, both political and sensorial, and this time I wanted to extend it into the depths of the country, into the heart of the country… This film is in some ways a road movie, but it works at different speeds. Gabbla was born of my intuitions when I was on location: when I went there, I saw lines, and the film had to reflect these lines. They are lines of circulation, those of the Chinese workers, those of the clandestine activists, those of the illegal immigrants, those of the different languages and musical forms, and those of the fictional characters that I was going to add. I tried, in a plastic and not sociological or journalistic way, to make this intertwining of lines of circulation perceptible.”

In the presence of Daniel Deshays

——

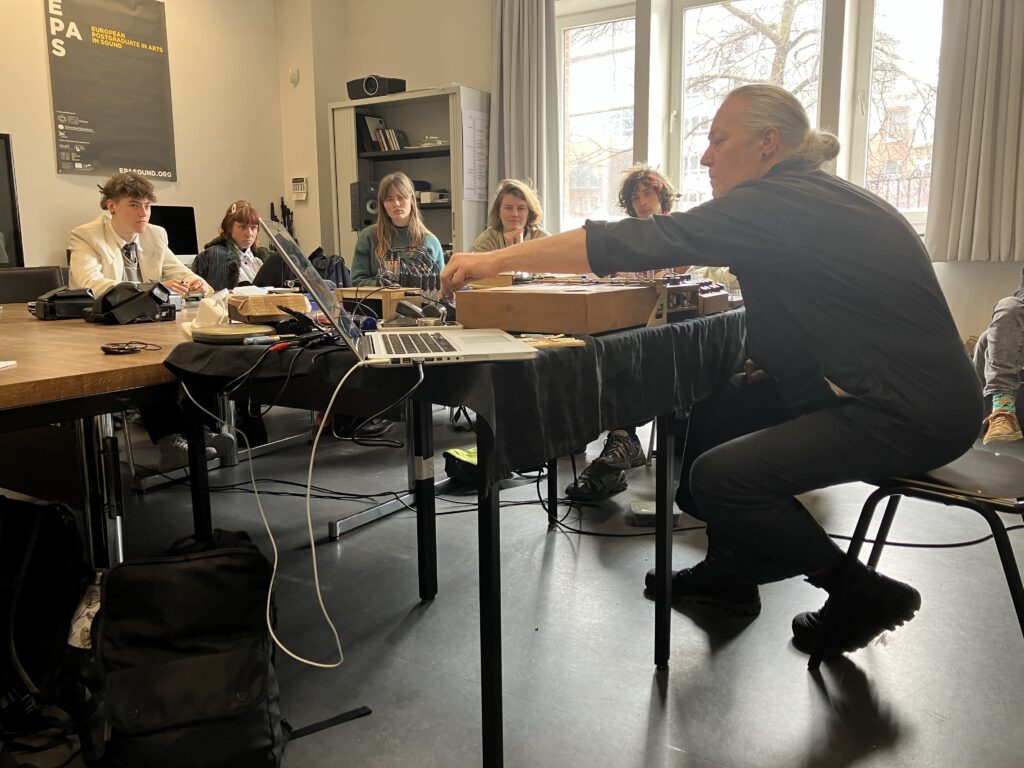

SEMINAR

Within the framework of ‘The Murmur of The World’ programme, we invited Daniel Deshays to reflect on the sonic dimensions of cartographic fictions. In his work as a sound engineer, researcher, teacher and writer, Deshays has developed an extensive reflection on the mise-en-scene of sound, as a creative object all too often considered subservient to the omnipotence of the image. For four decades he has contributed to the development of sound worlds in theatre, dance and especially cinema. He has collaborated with Robert Kramer, Tariq Teguia and Chantal Akerman, among others, whose work is represented in this year’s programme.

——

PERFORMANCES

Aurélie Nyirabikali Lierman was born in Karago, Rwanda, and grew up in Belgium. Fascinated by the narrative power of abstract sound and music, she often adds dramatic and documentary elements to a compositional structure. The common thread running through her work is her extensive collection of unique field recordings and soundscapes from East Africa. Sound by sound she transforms and models all those sounds she collected herself into something she describes as “Afrique Concrète”. In the context of The Murmur of the World, she will present a sonic and polyphonic portrait of Kariakoo, a district of the city of Dar es Salaam, the capital of Tanzania.

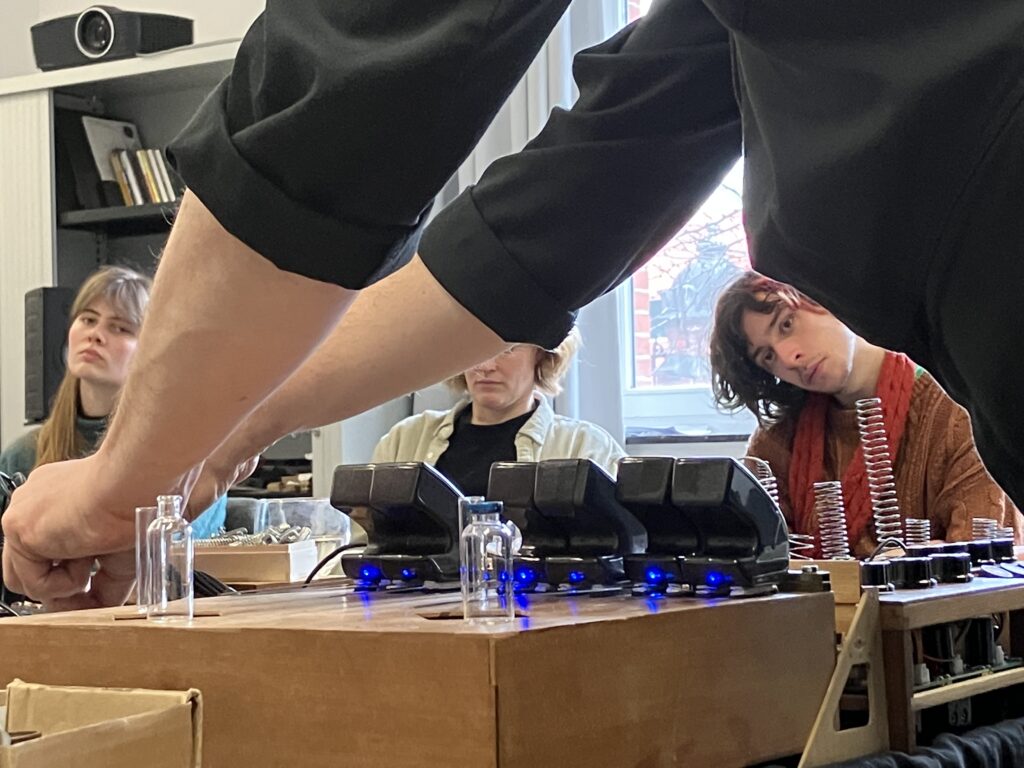

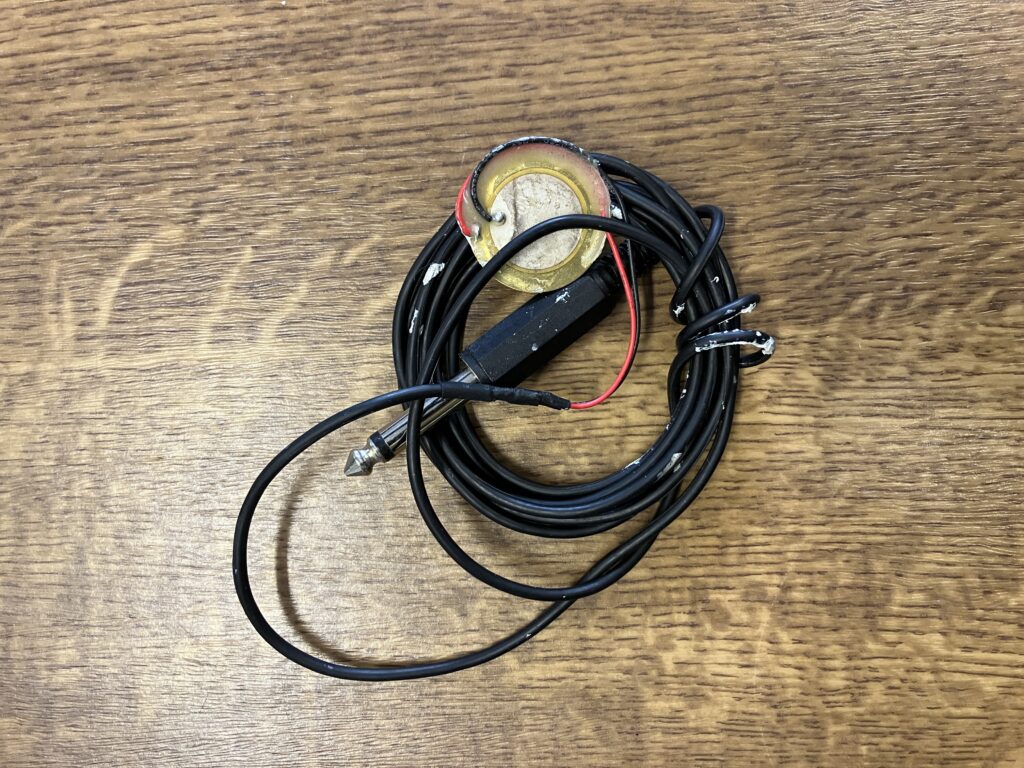

Lee Patterson listens and lets us listen to places and situations that are all too often considered mute. Whether working live with amplification or recording within an environment, he has pioneered a range of methods to produce or uncover complex sound in unexpected places. For example, he provided the sound recordings for Luke Fowler’s Being in a Place, a portrait of Margaret Tait’s life on the Orkney Islands, an archipelago in the Northern Isles of Scotland . In the context of The Murmur of the World, we invited Patterson to perform an alternative version of this portrait, based on the extensive sound recordings he made on Orkney.

——

WORKSHOP LEE PATTERSON @ KASK