Interesting read in the online NY times this week: an article by filmmaker Errol Morris, titled ‘It Was All Started by a Mouse’ (part 1 and 2), on war and photography, prompted by the sheer number of images of child’s toys amid the ruins of war.

“Why are there so many similar photographs? How did all these toys come to be photographed? What is the viewer supposed to infer from such a scene? Is it simply that the idea of children and their toys ratchets up the drama of a war photograph? The juxtaposition of innocence and destruction in one image? Is it just anti-war? Or is something more sinister involved? Is it disguised propaganda with a definite bias towards one side or another?”

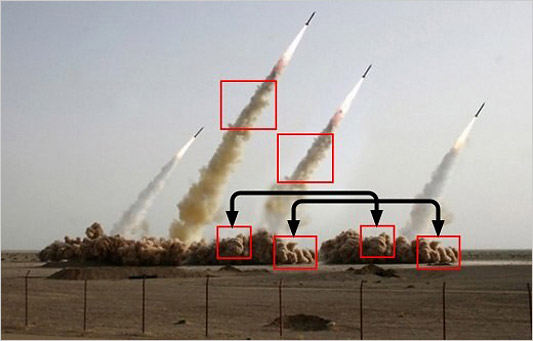

The article is, in some ways, a follow-up to his essay ‘Photography as a Weapon‘ (NY times, August 11, 2008 – the title of the piece is inspired by John Heartfield, by the way), in which he explored the manipulation of photography, in particular the photo of four Iranian missiles streaking heavenward, first published on July 10 2008 (on a sidenote, see also Oliver Laric’s video ‘Versions’) .

“For me it raised a series of questions about images. Do they provide illustration of a text or an idea of evidence of some underlying reality or both? And if they are evidence, don’t we have to know that the evidence is reliable, that it can be trusted? (…) The problem is not that the photograph has been manipulated, but that we have been manipulated by the photograph. Photoshop is not the culprit. It is the intention to deceive. (…) We should remember that the power of photographs comes not only from their ability to copy reality, but also to alter reality. Photographs can be used — to borrow Heartfield’s phrase — as weapons. They can be used to warn us about the dangers of impending war. They can also be used to ratchet up the blind forces of rage and unreason that drag us into conflict.”

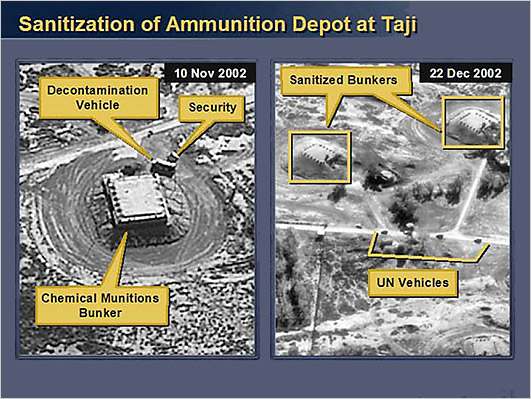

In the article, Morris also wrote: “You don’t need Photoshop. You don’t need sophisticated digital photo-manipulation. You don’t need a computer. All you need to do is change the caption“, referencing the photographs presented by Colin Powell at the United Nations in 2003. “Photographs that were used to justify a war. And yet, the actual photographs are low-res, muddy aerial surveillance photographs of buildings and vehicles on the ground in Iraq. I’m not an aerial intelligence expert. I could be looking at anything. It is the labels, the captions, and the surrounding text that turn the images from one thing into another.”

These issues are also addresses in ‘It Was All Started by a Mouse’, in an interview with Ben Curtis, Chief Photographer/Photo editor, Middle East, of the Associated Press, who has been criticised for a series of photos which appeared to be staged (see the article ‘The Reuters Photo Scandal. A Taxonomy of Fraud‘). Talking about the need for veracity and objectivity in photojournalism, Curtis refers to the “the Reuters incident” -the distribution of a doctered photo showing the aftermath of an Israeli airstrike on Beirut – which was uncovered by Charles Johnson on the Little Green Footballs blog (Johnson also coined the term “fauxtography”).

“I read the Reuters website after (the incident), and there was a lot of handwringing and reevaluation of their procedures. After the war, I read that Reuters was working with Adobe on some software component for Photoshop that would keep a record of all the changes that had been made in Photoshop, so that editors could see exactly what had been done to an image. It would aid in preventing manipulation of photographs. I found that quite interesting from a technical perspective, and I could see how such thing could be useful in the work flow of maintaining accuracy of images. This was one of the things that was in my head when I was writing the “in defense of captions” post — while that’s useful or could be useful, a technical solution alone is never going to solve the problem of accuracy in the media. You could take a photographer’s image straight from the camera, not even processed with Photoshop, put it on the wire, and it’s the caption that provides the accuracy for that picture. The caption is the place where it’s easy to mislead the reader.”

Here are some more excerpts taken from their discussion on the ethical issues surrounding the Mickey Mouse photograph (not posed or manipulated in any way, but, according to Morris “nonetheless a photograph that telegraphs a message”). Its caption read “A child’s toy lies amidst broken glass from the shattered windows of an apartment block near those that were demolished by Israeli air strikes in Tyre, Southern Lebanon, Monday, August 7th, 2006.”

Morris: “…Are we saying that there’s no damage done to these apartment buildings? That no children were killed? Even in the clearly Photoshopped image of the smoke over Beirut? Are we saying that Beirut was never hit by a bomb? That there were no apartment buildings leveled by Israeli drones? Is the crime posing? Or is the crime creating an image — even if it was produced ethically — that leads the viewer to a controversial conclusion. A photographer makes the decision to take a picture with a Mickey Mouse toy in the foreground. Is that a crime? Is it a crime if he found the toy and didn’t place it? Is it unacceptable because it suggests that children were killed?”

Curtis: “Yes. I’m looking at the Mickey Mouse picture again. A reader might infer from that, that a child had been killed in the attack and that this toy belonged to some child who is dead somewhere. Okay, you’re a reader, you can infer that if you want. But we’re not saying that. I’m not saying that. I’m saying it’s a child’s toy lying in the middle of a street after an air strike. That’s all I’m saying. If you want to infer from that what you want, that’s your prerogative, but you can’t then criticize us for that, you know? If I knew who that toy belonged to, if I knew his name and where he was now and what happened to him, that would be great. I’d include it in the caption. But I’m running around and I’ve got 10 minutes to get in, shoot pictures and get out of there, before maybe they’ll launch another air strike.”

…

Morris: “It’s narrative compression.”

Curtis: “It’s very compressed. You’re really trying to compress a huge amount of things. An air strike. Destruction. Some humanity. You’re trying to convey all of that in a single image. And, frankly, it’s pretty hard, especially when there’s not many people around.”

Morris: “Yes. Your stories are endlessly interesting, because you’re telling us about the exigencies of photography, that photography requires us to do certain kinds of things. The way in which stories are told by newspapers, by photographic convention, all influence how photographs are made, how they’re distributed, how they’re printed and published and disseminated, etcetera, etcetera. I’m not telling you anything you don’t know, but it’s interesting to take a step back and to talk to a photographer, particularly when we’re dealing with a controversial photograph, a supposedly posed photograph, and attempt to contextualize it thoroughly for the first time”.

Morris concludes:

“Photographs can give us a glimpse of the specific, of the particulars in a cauldron of seething politics. And yet, the meaning of what we’re looking at remains unclear. The Mickey Mouse photograph can function as pro-Arab or as pro-Israeli propaganda depending on the text it accompanies. Not just the text, but the mind-set, the mental captions, that inform how we see it. Mickey Mouse after all is “so human, that’s the secret of his popularity.” Images are plastic, malleable, and lend themselves to any and every argument.