Part of Courtisane Festival 2012, March 21 – 25, Gent.

A series of revisitations and reverberations: dialogues between then and now, between different generations and traditions, exploring ways of seeing and thinking cinema, politics, documentary and ethnography.

With works by Robert Gardner, Robert Fenz, Thomas Harlan, José Filipe Costa, Eric Baudelaire, Philippe Grandrieux

In the context of the research project “Figures of Dissent” (School of Arts/HoGent). Curated by Stoffel Debuysere.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

REVERBERANCE 1

Robert Gardner

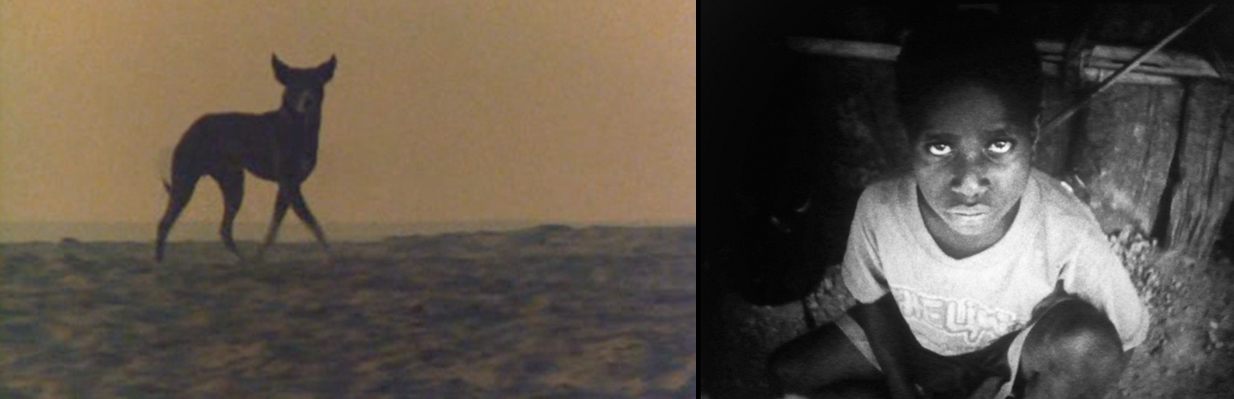

Forest of Bliss

US/IN, 1986, 35mm, col, stereo sound, 90’

Robert Fenz

Correspondence

US/DE, 2011, 16mm, b&w, silent, 30’

“Robert Gardner’s camera scans with precision and feels with sympathy – the objectivity of an anthropologist, the fraternity of a poet.”

– Octavio Paz

“It is apparent that only a certain kind of person will want to make ethnographic films”, is how Robert Gardner (1925) situated his own practice. “It will, above all, be those who sense the profound affinity that exists between the film medium and a desire to understand people.” As often scorned by scholars as applauded by the avant-garde, the work of Robert Gardner is of undeniable influence in the field of visual anthropology. As legendary fimmaker Stan Brakhage, a fervent defender, once put it, the question of whether Gardner is “An Artist, an Anthropologist, or WHAT?” is “SUCH a boring question once one has fully experienced his films.” It was while studying anthropology in the 1950s that Gardner started making films, some in collaboration with American painter Mark Tobey. His international breakthrough would come with Dead Birds (1963), a multi-awarded but controversial portrait of the Dani people in New Guinea. His lyrical and cinematographically exquisite portrayal of non Western cultures would produce many more master pieces in the following decades such as Rivers of Sand (1974), about the Hamar in Southwest Ethiopia, and Forest of Bliss (1986), filmed in the Indian city of Benares. The three abovementioned films are the starting point of Correspondence, Robert Fenz’s tribute to Gardner. Fenz literally followed Gardner’s footsteps in search for the shooting locations of the three films. The result is a poetic dialogue which at the same time pays homage to a way of filmmaking that has become obsolescent.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

REVERBERANCE 2

Thomas Harlan

Torre Bela

PT, 1975, 16mm, color, stereo sound, Portugese spoken, 106’

José Filipe Costa

Linha Vermelha

PT, 2011, video, color, stereo sound, Portugese & French spoken, English subtitles, 80′

“My works don’t tell political stories. They rather document a political alertness, a clairaudience for certain constellations. My films, each for themselves, are generally useless for the purpose of a position or theory.”

– Thomas Harlan

“I am the son of my parents. That is a disaster. It has determined me”, declares author, dramaturge and filmmaker Thomas Harlan (1929-2010) in the interview book ‘Hitler war meine Mitgift’. Harlan, who grew up in Nazi-Germany, once shared a table with Adolf Hitler, accompanied by both of his parents, actress Hilde Körber and filmmaker Veit Harlan, the director of the infamous anti-Semitic propaganda film Jud Süß. It is a heritage that he could never get rid of and the appalled son would take upon himself the sins of his repent-less father. His whole life Harlan would strive for truth as the only possible justice: he spent years in the Polish archives, looking for proofs of German war crimes; in Rome he joined the radical leftist group “La Lotta Continue” and travelled to wherever the spirit of revolt and revolution emerged. In 1975 Harlan was in Portugal where, in the aftermath of the Carnation Revolution, various movements of resistance and initiatives of land occupation were developing. That is where he shot his first film, a documentary about the occupation of the Torre Bela estate, which according to critic Serge Daney represents a condensation of “all the key ideas – materialised, embodied – of political and theoretical leftism from the past decade”. More than 35 years later another filmmaker, José Filipe Costa, revisits in Linha Vermelha the production process of the much discussed film, which Harlan himself once described as in “complete opposition to what documentary should be”: a seemingly pure “observational” cinematographic document that has become over time a controversial historical object.

(See also ‘The militant ethnography of Thomas Harlan‘ By Serge Daney)

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

REVERBERANCE 3

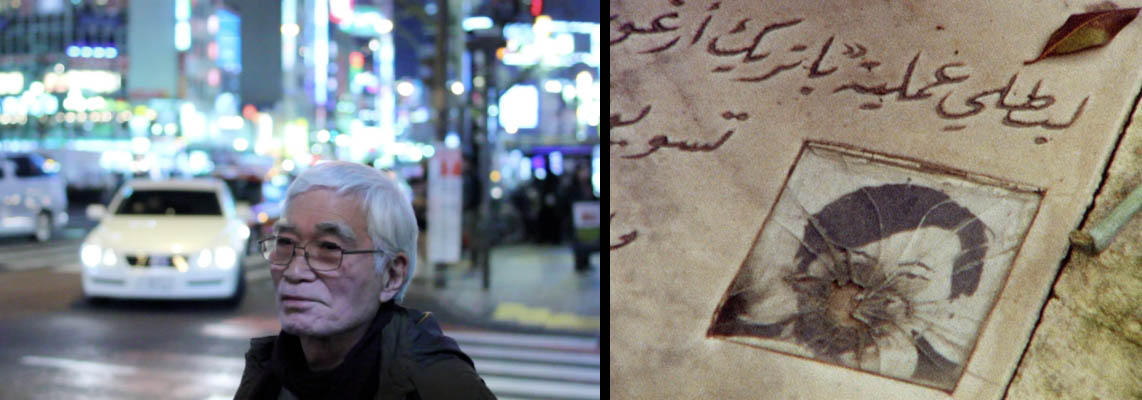

Eric Baudelaire

The Anabasis of May and Fusako Shigenobu, Masao Adachi, and 27 years without Images

FR, 2011, Super8 to video, colour and b&w, English, japanese, french spoken with English subtitles, 66‘

Philippe Grandrieux

Il se peut que la beauté ait renforcé notre résolution – Masao Adachi

FR, 2011, video, color, stereo sound, Japanese and French spoken with English subtitles, 75′

“Shooting a gun or shooting with a camera, it doesn’t make a difference to me”

— Masao Adachi

“The revolution has been continuously my main subject” says Masao Adachi (1939). “People Said: Revolutionary Cinema. I said: No. It’s Cinema for Revolution.” Of all the filmmakers that would be inspired by the spirit of resistance and utopia of the 1960s and 1970s, Adachi is without a doubt the most radically and perseveringly militant. Armed with a camera or with a gun: it made no difference to him. To him, both weapons served as possible intervention tools in the fight against political and social oppression. With his surrealistically tinted and politically provoking experiments he inscribed himself rapidly as part of the so called “new wave” currents that shook Japanese culture of the time. In 1971, after visiting the Cannes Film Festival, Kôji Wakamatsu and Adachi travelled to Lebanon to make a propaganda film in support of the Arab fight against Isreali occupation. In 1974 Adachi returned to Palestine, with the idea of making a second film. He would end up staying 26 years, at the service of the Palestinian cause. In 1997, under the pressure of the Japanese authorities, he was incarcerated in Beirut. He was extradited to his country three years later, where he remained in prison for two more years. Two French filmmakers have recently made, independently from one another, cinematographic portraits of the Japanese filmmaker. One from a distance, the other on the skin. Eric Baudelaire confronts landscape images from Beirut and Tokyo with the recollections of Adachi and Maya Shigenoby (daughter of Fusakao, one the leaders of the Red Army). Philippe Grandrieux translates a brief meeting into an intuitive and sensory combustion of image, sound, light and colour.