“I’ve always known that I was outside the main, mercantile stream. I have been placed in an environment that would have its name changed now and again: avant-garde film, experimental film, independent film etc. I have tried to create film work so that it is capable of communicating to people outside of a limited dialogue within an esotoric, avant-garde or a cultish social form. Jargon I don’t like.”

— Bruce Conner, in an interview with William C. Wees

The great filmmaker and collage artist Bruce Conner died on July 7th 2008. Conner’s films are considered as pivotal in the history of avant-garde cinema and cornerstones in the art of collage or “found footage” filmmaking. There aren’t many films that had as much impact as his debut film, ‘A Movie’ (1958), a film in which he, inspired by the surreal art of zapping (UPDATE: or perhaps it’s better to talk about “channel hopping”, see comments below), the “coming attractions” trailers in cinema, and the Marx Brother’s comedy classic ‘Duck Soup’ (especially the final battle scene, featuring the stock footage of monkeys and elephants running to save the army under siege), juxtaposed footage from B movies, newsreels, soft-core pornography, and other fragments. Patricia Mellencamp has pointed out that “A Movie is a history of cinema as catastophe” that “becomes the history of Western culture or the United States – a history of colonial conquest by technology, resolutely linking, sex, death, and cinema – questioning our very desire for cinema (a fetishistic, deathly pleasure within the safe, perverted distance of voyeurism, economic superiority, and national boundaries)”. In an interview with William C. Wees (1991) Conner explained that by observing cinema trailers and the absurd narrative techniques in televison series it became apparent to him that “you can create an emotional response which is very different from what was socially agreed upon as a narrative structure.” Conner paid attention to the things that tend to be thrown away and taken for granted as not serious, because “if you want to know what’s going on in a culture, look at what everybody takes for granted. Put your attention on that, rather than on what they want to show you. I view my culture here in the United States as I would regard a foreign environment. That is, it’s supposed to be my culture. I don’t feel that way.” In his films , Conner reflected on the relationship between the individual, the image and history in recent decades, decided by the permanent presence, in constantly changing form, of images, mostly television – the accelerating rythm in the editing, the change from film to video, the aesthetic exchange between cinema and television, the arrival of non-stop and live reporting on such networks as CNN and their associated fictionalization of the news. These transgressions have had an intrusive impact on our relationship with reality. “My films are the ‘real world’. It’s not fantasy. It’s not a found object. This is the stuff that I see as the phenomena around me. At least that’s what I call the ‘Real World’. We have ‘Reality Shows’ presented to us regularly. The most prevalent one is the five minutes ‘reality show’ – the five minute news. If you listen to a news program on the radio it may report ten events in a row. It’s no different than ‘A Movie’. Something absurd next to a catastrophe next to speculation next to a kind of of instruction on how you’re supposed to think about some political or social thing. You know: ‘President Bush had lunch with his wife and went to Kennibunkport, Maine, today. Fifty thousand people died in Bangladesh in a horrible disaster. Sony says they’re going to produce a new three-dimensional hologram television set which will be released sometime in the 21st century.’ GaGa, GaGa. I mean this is comic book time.”

“If they give you lined paper, write the other way.”

— Bruce Conner

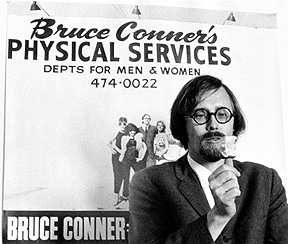

Other Bruce Conner classics include ‘Breakaway’ (1966), ‘Report’ (1967), ‘Looking for Mushrooms’ (1967), ‘Crossroads’ (1976, the still is taken from this film) and ‘Valse Triste’ (1977) (see here for an extensive view). Conner also did pre-production work on Peter Fonda’s 1970 film ‘The Hired Hand’ (he was pals with Hollywood bad boys such as Dennis Hopper – who took the picture below, Dean Stockwell, Warren Oates and Peter Fonda) and briefly returned to filmmaking to do videos for Devo (Mongoloid), Brian Eno and David Byrne (‘America is Waiting’ and ‘Mea Culpa’, both from the album ‘My Life in the Bush of Ghosts’). Conner also became involved in the San Francisco punk scene as a staff photographer for fanzine Search and Destroy. A corrosive aesthetic of outraged idealism that Conner had anticipated by decades, punk was tailor-made to his sensibility, and he spent most of 1978 at a punk club called the Mabuhay. In an interview with Kristine McKenna he said: “I lost a lot of brain cells at the Mabuhay. During that year I had a press card so I got in free, and I’d go four or five nights a week. What are you gonna do listening to hours of incomprehensible rock ‘n’ roll but drink? I became an alcoholic, and it took me a few years to deal with that. (…) I’ve always been uneasy about being identified with the art I’ve made. Art takes on a power all its own and it’s frightening to have things floating around the world with my name on them that people are free to interpret and use however they choose. Beyond that, I’ve seen many cases where artists have been defeated because the things they made came to be perceived as being more important then they themselves were. De Chirico struggled to develop a new style of painting, but nobody was interested-they only wanted to show his own work. This is something I’ve experienced myself, and it’s a highly unbalanced situation because essentially the artist is denied a voice about the course of his own life and work.”

A few years ago, Bruce Conner withdrew all his films from distribution (which was mainly done by Canyon). Apparently, they are being restored right now. However, in the experimental filmworld there is quite a bit of concern about his legacy, fearing that vultures are already swooping down on his wife. This fear is well founded: for example, recently the estate of another American avant-garde hero, the late Jack Smith, has been sold to the Gladstone Gallery in New York City. The ownership of all his photographs, paintings, slides, films, etc. has been transferred. As Jerry Tartaglia (a friend of Smith, who also worked on the restoration of his films) wrote: “whether the Gladstone Gallery chooses to avail itself of the reliable resources that actually care about and understand the work, or chooses to be taken in by the salivating vultures that are perched in their ego driven clouds of unknowing, remains to be seen.”

Right after Conner’s death, lots of posts and articles appeared on the net, linking to YouTube and other video platforms hosting unauthorized dupes of Conner’s films. All these videos are gone now (you can track this process via YouTomb). Ray Pride posted this message on his MovieCityIndie blog, written by a lawyer representing Jean Conner, the filmmaker’s widow: “Bruce was firmly opposed to display of his films on-line, and on his behalf as an attorney I made numerous requests for removal. Now that Bruce has died, all copyrights are now held by Jean Conner (Bruce’s wife), and she has explicitly directed that I request and otherwise take action to have all on-line postings of Bruce Conner movies removed immediately.” This stirred quite a bit of controversy. Via Rhizome, Ed Halter wrote a call to bigger sites such as BoingBoing who paid tribute to Conner’s death and might help to bring this issue to a bigger YouTube audience. He writes,”Hi there. I write for a site devoted to net art and technology art, and wrote an obit for Bruce Conner yesterday for the site. Although Conner wasn’t a new media artist, part of this was to honor him as a pioneer of found footage re-editing, which has become such a major part of online culture and recent internet art. However, within the very short time span between writing and publishing this piece, all the videos of Conner films that I linked to in his obit were removed from YouTube and other sites –no doubt due to the attention they’ve been receiving in online obituaries elsewhere. It is widely know within the experimental film community that, towards the end of his life, Conner removed his films from general circulation (perhaps on the logic that they could be editioned as ‘video art’), and now whoever is handling his estate (a gallery? lawyers?) deems it necessary to remove any trace of his work from the internet as well. I think this irks me more than usual because, as an ardent fan of experimental film, Conner was one of my first loves‹-made possible by a VHS of his films at my local video store. I wrote this obit for Rhizome in the hopes that younger artists or those who aren’t so aware of avant-garde film could see that he is the great forefather of video remixing, but now, thanks to the short-sightedness of those who think they are protecting his legacy,this will remain an uphill battle, and I fear that the true genius of his work will be denied to a new generation. It is truly a shame and a disservice to his memory that some of his works couldn’t be made available online, if only to celebrate his life and influence. All this becomes much more ironic given that, of course, I doubt if Conner ever got permissions for the footage he used in his films. Had the originators of those images been as draconian in their time as his estate is being now, those films would never have been possible.”

This again relates to the ongoing discussions on the economics of avantgarde film and the access vs. quality issue (see my earlier post on the Ubuweb controversy). Conner’s reasons for not wanting his work posted online apparently had to do with not wanting to cut into his film rentals and sales, and also because the loss of image quality didn’t serve the films. J Gluckstern answers Haller with some clear insights: “I’m not sure we can presume that our appreciation and recognition of the value of easy access to Conner’s work (for creative, inspirational and historical reasons) syncs up with what moved him to recombine those images in the first place. He had his reasons then. And we need to give him the benefit of the doubt that his later actions reflected his original and ongoing intentions for what the work was about. Now it’s up to his estate/family to decide what happens next, and so far, it seems we’ll be seeing even less of Conner’s work on anything but film.”

Several related issues of intellectual property and appropriation came up in a post by Caspar Stracke, who also wrote about Conner’s films being available via YouTube. He brings up the case of Mark Charles Brown, who made a homage to Conner’s ‘Take The 5-10 To Dreamland’, which he titled ‘Erasing Dreamland (Accidentally Erased Bruce Conner)’. Searching through YouTube’s metadata, he collected alternative clips depicting the same objects or similar imagery as in Conner’s film and then juxtaposing them with the original. Apparently the creation of this film lead to the erasure of Bruce Conner’s “original” film from the YouTube network, “due to its content being used with out the artists permission.” But he lifted all the content from YouTube BEFORE Connor’s piece was removed, then mixed with other YouTube content, which lead to a weird situation. On the YouTube page it says that “the film (the homage, sd) currently exists in copyright protection limbo, as the footage sampled was legally obtained from YouTube. As outlined within the terms of use agreement associated with uploading a video to YouTube, the content of Bruce Conner’s film existed outside the realm of copy protection while it was still present on their network, regardless of Conner not being the original poster of the film. Furthermore, the copyright management status of the video enters an even stranger space upon the realization that both films were created using found footage.” The confusion about intellectual property in the digital age in a nutshell.

All side issues left aside, let us just hope Bruce Conner’s work lives on and can be seen, in its original form (that is: preferably on film, or at least a format that has similar qualities), but also in mashups, updates, homages and remixes, in new contexts, on new rhythms.

(For those who dig deep in the web, Conner’s films are still there. For example… For those interested in seeing the real thing: we will be showing ‘A Movie’ (a 16mm copy owned by the Belgian Filmarchive) in a special screening at Muhka Media in Antwerp on September 19. More info later)

UPDATE: One of the Walker Art Center blogs has an interesting discussion in the comments about the YouTube take-downs and the access vs quality debate, including a couple comments by Dr. Patrick Gleeson, one of Bruce’s music collaborators. Some fragments:

“He was a passionate guy and if you will notice, one of the themes that runs through Bruce’s work is the destructive power of technology–not that technology was bad; Bruce wasn’t a Luddite–but that the consequences of its careless use were far worse than most of us realize. The U-Tube is a fairly obvious example of the degradation of art that Bruce found abhorrent.”

“Bruce was very competitive in some ways–his roots were Middle American–but I think questions of distribution, fame, money, public access to his art, etc.–the things we often count up when assessing success, were secondary to Bruce. That’s not unusual–a lot of artists, probably most artists, feel that way. We want and hope to be paid, but that’s not exactly why we “do” art. However: what makes Bruce different from many artists–and I think this is the part you’re somewhat stubbornly not getting–is just how extremely secondary these concerns were when weighed against the things that for Bruce really counted–in a lot of ways, particularly later in his life, he actually opposed and disliked the art market–as his enduring and frustrated dealers would certainly affirm. For Bruce there was centrally and primarily the art experience. (…) He knew exactly how he wanted his art to be experienced and he was extremely, sometimes maddeningly, detailed and exacting about the terms. This had absolutely nothing to do with money, distribution, etc.–it had to do with how this art experience, or some legitimate variation of it that could possibly be made available to someone else. He felt passionately that a lot of what passed for the art experience in contemporary life was a cruelly stupid replacement for the real thing–a cuckoo’s egg in the robin’s nest. He found it deeply offensive. He proposed certain terms about how others could share in that experience not because he was cultural snob, but because he deeply believed that except through those terms the art-experience didn’t exist. In other words, he was trying to share with us everything that could be shared. (…) To propose that Bruce, and now his estate, ought to allow YouTube or other down-pixeled copies to circulate because of possible monetary benefits would, I’m afraid, have enraged him. (…) I think there’s a belief underlying part of this discussion that the artist, here Bruce of course, has some kind of obligation to share his experience with as many persons as possible–it’s a beautiful experience and should be shared. Where does this obligation come from? I don’t think it exists; it’s a pseudo-populist fantasy and probably has more to do with our Puritan cultural heritage whereby we save ourselves by good works and reveal god’s pleasure in us through our worldly success. Bruce was just making art. The distribution of it, the marketing of it–all that really got him down. I think he thought that indulging in it might even be a character flaw–he spent considerable energy the past few years of his life trying to purge himself of the distraction.”

Some interviews: SFB Guardian (2005), LA Times (1990), Smithsonian (1973). Some Notes on the Films of Bruce Conner by William Moritz and Beverly O’Neill (1978).