“Plagiarism is necessary. Progress implies it. It holds tight an author’s phrase, uses his expressions, eliminates a false idea, and replaces it with just the right idea.”

— Comte de Lautréamont (also known as Isidore Ducasse), ‘Poésies II’ (1870)

“There are very few original ideas. Plagiarism is the name of the game in advertising. It’s about recycling ideas in a useful way.”

— Philip Circus, an advertising law consultant, quoted in an article in the Independent

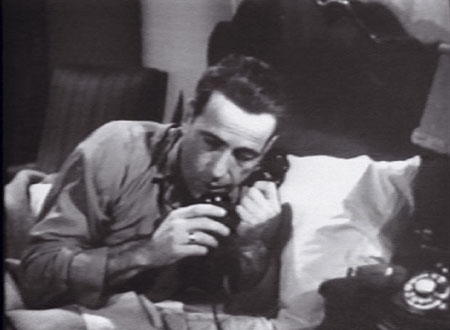

Here’s an interesting case in the context of “remix culture”, and the ongoing debates on plagriarism, quotation, simulation, collage etc . You’ve probably seen Apple’s “Hello” ad for the iPhone, showing a succession of snippets of actors from Hollywood films answering phones. Now, for those of you who know a bit about the extensive use of collage and détournement strategies in “experimental” film, this idea sounds familiar. Indeed, Christian Marclay’s 1995 film ‘Telephones’ comprises a similar montage, although it features different footage. As it turns out, Apple did contact Marclay before publishing the ad, to get permission to use the concept. He refused, but they took the idea anyway. Marcley, not being too pleased at first, talked to a lawyer about taking legal action over the ripoff, but was told “there’s nothing I can do about it. They have the right to get inspired”. Later he backed off (contradicting himself a bit): “this culture’s so much about suing each other that if we want to have anything that’s more of an open exchange of ideas, one has to stop this mentality. I’m just honored that they thought my work was interesting enough that they felt they could just rip it off.”

By the way, Marcley is not the first artist who seems to have “inspired” the commercial people of Apple. Last year, Colorado-based photographer Louis Psihoyos claimed that Apple ripped off his image of a wall of videos in its imagery for the Apple TV. Apple had actually been negotiating with the photographer for the rights to use the image but backed out of the deal and went ahead and used the imagery without permission. Furthermore, there has been some controversy about another Apple ad, which seems to be a shot-for-shot recreation of The Postal Service’s music video for ‘Such Great Heights’.

Anyways, compare the Marclay and iPod videos:

There’s a whole tradition of artists and filmmakers appropriating images and sounds from cinema and televison, often commenting on consumer culture and challenging the idea of originality itself (see our ‘Ghosting the Image‘ film program). But here the tables are turned. In recent years a number of advertising campaigns have seemed to draw their inspiration directly from high-profile works of contemporary art. An article in Asian Age quotes Donn Zaretsky, a lawyer in New York who specialises in art law, is often approached by artists who perceive echoes of their own work in advertisements “They increasingly seem to be getting into the territory of blatant rip-offs.” The law governing the unauthorised use of copyrighted images and ideas, he said, is notoriously murky. “Copyright law doesn’t protect ideas, it only protects expression. The question is, where do you draw the line?”. There have been a few notable cases in which artists successfully sued advertisers for copyright infringement. For example, in May 2007 a French judge ordered the fashion designer John Galliano to pay about $270,000 to the photographer William Klein in a dispute over a series of magazine ads that mimicked Klein’s technique of painting bright strokes of color on enlarged contact sheets. But in many cases, “originality” is hard to prove, especially in the light of the well known axiom saying that there is no copyright in an idea but only in an embodiment of that idea.

In 1998 Artist Gillian Wearing complained that a commercial by BMP DDB for Volkswagen borrowed too heavily from her ‘Signs’ series. Both feature people holding paper signs that express how they really feel in contrast to their appearance. BMP DDB claimed that, while its creative team were “aware” of her work, the clip also took inspiration from a Levi’s campaign for its Dockers brand (which ironically, Wearing also contacted her lawyer over, and gave permission for) and the video for Bob Dylan’s ‘Subterranean Homesick Blues’ in which the singer-songwriter holds up cue cards as he sings (which is actually a segment of D. A. Pennebaker’s film ‘Don’t Look Back’). As it happens, that last video was recently appropriated by Ramon & Pedro as a commercial for the Macbook Air.

UPDATE: and this is ‘Subterranean House (Oonce Oonce)’ by Michael Bell-Smith, which was recently part of an exhibition titled “Montage: Unmonumental Online” in the New Museum, NY.To continue the story, Wearing wasn’t pleased at all: “what really hurts is that it stops me doing my work because people think I’m working for an advertising agency”. A year later, she also accused M&C Saatchi of using the idea of her film ’10-16′ – a succession of adults are shown talking in a confessional style straight to camera, overdubbed with children’s voices – in an advertisement for Sky television (by the way, Charles Saatchi himself owned an edition of that piece). M&C Saatchi’s chief executive, Moray MacLennan, said: “Lip-synching in advertising is not a unique or original idea. There are other ads on the box that use the technique. It’s commonly used in advertising and is not a new thing.” Wearing dropped her legal action when the artist Mehdi Norowzian was ordered to pay pounds 200,000 costs in 1999 after he lost a case against Guinness, which he accused of breach of copyright in an advertisement featuring a dancing man. Norowzian used the “jump cutting” technique in his film ‘Joy’, resulting in the image of a man dancing jerkily to music. The accused agency accepted that it had seen this film in producing the advert for Guinness, which portrayed a man performing a series of dancing movements while waiting for his pint of Guinness to settle – the actor, Joseph McKinney, had been shown the film more than once and he gave evidence that he had been told by the agency to imitate, emulate and expand upon Joy. But the judge held in Guinness’s favour and confirmed that advertising agencies can lawfully use artists’ ideas or even the format of a particular work without infringing copyright. He said: “no copyright subsists in mere style or technique… If, on seeing ‘La Baignade, Asnieres at the Salon des Artistes Independants’ in 1884, another artist had used precisely the same technique in painting a scene in Provence, Seurat would have been unable, by the canons of English copyright law, to maintain an action against him.”

Commenting on these cases, an article in the Guardian quoted a copyright lawyer saying: “A lot of visual art is seen as very irrelevant and useless, but clearly advertisers are taking a different view and recognising that visual artists are at the forefront of the culture and their messages can be very potent. Advertisers have exhausted and got bored with the books of great art and extended into images by artists that people don’t know. The one thing that hasn’t changed is the advertisers’ reluctance to pay.” Another notorius case of the last years, is the one of Swiss artists Peter Fischli and David Weiss. They have turned down numerous requests from ad agencies interested in licensing their award-winning 30-minute short film, ‘Der Lauf der Dinge’. Produced in 1987, it follows a Rube Goldberg-style chain reaction in which everyday objects like string, balloons, buckets and tires are propelled by means of fire, pouring liquids and gravity. Yet in April 2003 Honda ran a two-minute television commercial for the ‘Honda Cog’ (directed by Antoine Bardou-Jacquet, a well-known filmmaker of high concept ads and music videos, and a good friend of Michael Gondry. The clip is produced by Wieden+Kennedy London), in which various parts of a car form a domino-like chain reaction that culminates when an Accord rolls down a ramp as a voice-over intones, “Isn’t it great when things just work?”. At the time Fischli told Creative Review magazine (echoing Wearing’s complaint): “We’ve been getting a lot of mail saying, ‘Oh, you’ve sold the idea to Honda.’ We don’t want people to think this. We made ‘Der Lauf der Dinge’ for consumption as art. Of course we didn’t invent the chain reaction and Cog is obviously a different thing. But we did make a film the creatives of the Honda ad have obviously seen.” W&K’s creative director Tony Davidson answered that Fischli and Weiss’s film was only one of the inspirations for the ad (again an echo) and argued: “Advertising references culture and always has done. Part of our job is to be aware of what is going on in society. There is a difference between copying and being inspired by.”

Lots of food for thought here, not only about the tension between appropriation and inspiration, participation and exploitation (legal and ethical – what’s the distinction between fleeting reference and wholescale rip-off, and how and when does it really matter?), but also about the future of art and cultural knowledge, in a network society characterised by constant feedback loops: how, for example is one to evaluate the music-video aesthetics of Bardou-Jacques and his team on the Honda Cog, compared to the certified ‘documenta-to-Tate Modern’ art-world status of Fischli & Weiss? How to square the gallery work of Christian Marclay’s with Apple’s hip ad?

UPDATE: someone mentioned a Belgian example. Segments of the short video ‘Little Figures’ by Sarah Vanagt have apparently been copied in an ad for BGDA / ORBEM (now called ACTIRIS, responsible for the free provision of services in order to achieve full employment and the balanced development of the Brussels labour market). Both feature specific shots of Brussels statues with a voice over – in ‘Little Figures’ three migrant children stir up a imaginary conversation between the statues, while in the ad the voice over is about taking your future in your hands etc.