THE PIONEERING WORK OF ATTEYAT AL-ABNOUDY, ASSIA DJEBAR, JOCELYNE SAAB, HEINY SROUR

In the context of Courtisane Festival 2021 (Gent, 20 – 24 October 2021). Curated by Stoffel Debuysere in collaboration with Reem Shilleh and Mohanad Yaqubi (Subversive Film).

« Nous toutes, du monde des femmes de l’ombre, renversent la démarche: nous enfin qui regardons, nous qui commençons.»

“All of us, all of us who come from the world of women in the shadows, are turning the direction around: at last it is we who are looking, we who are making a beginning.”

– Assia Djebar

When exploring a cinematic history as extensive and rich as that of the Arab Mediterranean, one is faced with an exhilarating range of forms and manifestations. From the silent era up to the present, the regional cinemas of the Maghreb and the Mashriq have produced a myriad of remarkable works. Yet, when poring over the canonical historiographies of cinema, one cannot help but being struck by their relative obscurity, which is even more striking when it comes to films that have been made by women. Although there has been a notable rise of Arab female film directors in recent decades, the work of many pioneers tends to remain painfully neglected.

The aim of this program is to address this obscurity and revitalize the work of four filmmakers whose films remain overlooked and underscreened: Atteyat Al-Abnoudy, Assia Djebar, Jocelyne Saab and Heiny Srour. Coming from different backgrounds and regions, these filmmakers all started to produce films in the 1970s, at a moment of great political and cultural ferment. Often working against the grain, they set out to attend to voices and stories that were at risk of being drowned out by official History. While each of these filmmakers developed different approaches, their works explore shared themes such as memory and identity, oppression and liberation, violence and exclusion, and the social and political role of women in Arab societies and histories.

Each of these filmmakers, whose work is shown side by side here for the first time, has been shaped by different traditions and realities. For the Arab woman filmmaker exists no more than the Arab woman. Accordingly, this program seeks to follow Assia Djebar’s appeal to “not to presume ‘to speak for’ or, even worse, ‘speak on’, barely speak near to, and if possible right up against.” In order to explore in depth the singularities as well as the communal resonances of the distinct bodies of work in this program, a variety of guests have been invited to speak “right up against” the films. Furthermore, an accompanying publication brings together a selection of writings and interviews which have been newly published or translated on this occasion.

——

This program consists of a selection of films from the period 1970-1990 which will be shown in the best available quality. This program was developed with the support of The Arab Fund for Arts and Culture (AFAC) and CINEMATEK.

On the occasion of this program, Courtisane and Sabzian have collected a series of writings and interviews in a small-edition publication. With the support of KASK / School of Arts.

Thanks to: Viktoria Metschl, Christophe Piette, Céline Brouwez, Mireille Calle-Gruber, Heiny Srour, Mathilde Rouxel, Asmaa Yehia El-Taher, Alexander Horwath, Regina Schlagnitweit, Tobias Hering, Mai Abu ElDahab, Ahmed Bedjaoui, Stephanie Van De Peer, Léa Morin, Mary Jirmanus Saba, Natasha Marie Llorens, Debra Zimmerman, Colleen O’Shea, Yasmin Desouki, Olivier Hadouchi, Salim Aggar, Aziz Kourta, Tewfik Abdelkader Mahi, Emma Hedditch, Louise Shelley, Matthieu Grimault, Omar Jabary Salamanca, Tamer El Said, Stefanie Schulte Strathaus and many others …

——

Assia Djebar

“Can it be simply by chance that most films created by women give as much importance to sound, to music, to the timbre of voices recorded or captured unawares, as they do to the image itself ? It is as though the screen had to be approached cautiously and be peopled, if need be, with images seen through a look, even a short-sighted, hazy look, but borne on a full, commanding voice, hard as stone but fragile and rich as the human heart.”

Assia Djebar (1936-2015) was born Fatima-Zohra Imalayen in Cherchell, Algeria, to a family of Berber origin. She was the first Algerian woman to attend the École normale supérieure de jeunes filles outside Paris. During the Algerian War of Independence (1954-1962), she worked with Frantz Fanon for the newspaper El moudjahid, conducting interviews with Algerian refugees in Tunisia and Morocco, before going on to teach history in Rabat and later in Algiers. Between the ages of twenty and thirty, she wrote four novels. But in the mid-1960s, she decided to abandon writing in French, the language of Algeria’s colonizer. Cinema offered her new ways to approach language as well as the world of the women in her home region, which sharpened her attention to sounds spoken and sung. “I made the decision to make a first film, not knowing really if I’m a filmmaker, I think in November 1975: because it was the day of Pasolini’s death. His relation to popular poetry, to the spoken dialects of these regions, which he has conveyed in a certain way on the screen, is what I felt concerned about.” To film The Nouba of the Women of Mount Chenoua in 1975-77, Assia Djebar went back to the mountain of Chenoua in order to listen and give voice to the oral histories as transmitted by otherwise silenced women. The film was awarded with the Critics’ Prize at the 1979 Venice Film Festival, but was received with hostility in Algiers, where it was considered as too “personal” and thus anathematic to the nationalist project of decolonized Algeria. In 1980, she resumed her career as a writer with Women of Algiers in Their Apartment, a collection of stories expressing Algeria’s collective memory through polyphonic narratives by female voices. This book was going to be the seed for a film on the urban women of Algiers, intended to complement its other half on the rural women of the hinterland. Instead, for what turned out to be her final film, The Zerda or the Songs of Oblivion (1978-1982), she spent two years sifting through archival footage shot by French colonizers in the first half of the twentieth century, weaving it into an alternative vision of the history of the Maghreb. As Assia Djebar grew to be one of the most important figures in North African literature, she continued to raise the issue of women’s language and the circulation of women’s voices, all the while developing what she has termed her “own kind of feminism.”

La nouba des femmes du Mont Chenoua (The Nouba of the Women of Mount Chenoua)

Assia Djebar, DZ, 1977, 16mm, 115′

“This film, in the form of a nouba, is dedicated, posthumously, to Hungarian musician Béla Bartók, who had come to a nearly mute Algeria to study its folk music in 1913; and to Yaminai Oudai, known as Zoulikha, who organised a resistance network in the city of Cherchell and its mountains in 1955 and 1956. She was arrested in the mountains when she was in her forties. Her name was subsequently added to the list of the missing. Lila — the protagonist in this film — could be Zoulikha’s daughter. The six other talking women of Chenoua recount fragments of their lives. The Nouba of the Women is their moment. But the Nouba is also the Nouba of the Andalusian music in its particular rhythmic movements.“

La Nouba borrows the structure of the nouba, a five-part traditional Andalusian music form, to tell the story of a woman who returns to the town of her childhood fifteen years after the violent War of Independence. Reading the history of her country as written in the stories of women’s lives, La Nouba des Femmes du Mont Chenoua is an engrossing portrait of speech and silence, memory and creation, and a tradition where the past and present coexist.

Arabic spoken, English soft-titled. Print courtesy of the Centre Algérien de la Cinématographie.

Introduced by Viktoria Metschl.

La Zerda ou les chants de l’oubli (The Zerda or the Songs of Oblivion)

Assia Djebar, DZ, 1982, DCP, 60′

“In a Maghreb region subjugated by colonial domination and reduced to silence, photographers and filmmakers invaded to capture us in images. The Zerda is their bleak “celebration” of our society. In stark contrast to their images with their penetrating gaze, we attempted to create an alternative vision, offering glimpses of a daily life held in contempt … But above all, behind the veil of this now exposed reality, we collected anonymous voices that re-imagined the soul of a reunified Maghreb, and of our past.”

As a historian, Assia Djebar had been asked by Pathé-Gaumont to sift through some old film reels, which turned out to be discarded newsreels on the colonies, focusing on the everyday life of the Maghrebi peoples from the early twentieth century to the Second World War. Out of the colonial discards, Djebar, in collaboration with poet Malek Alloula and composer Ahmed Essyad, wove together footage of the Zerda ceremony with poetic voice-overs recounting the lived experiences of indigenous Algerians, interspersed with “songs of oblivion” to recognize traditions that are being lost to colonialism even as they are tokenized by and subjugated to the colonial gaze.

Arabic / French spoken, German & English subtitles. Digital Restoration by Arsenal – Institute for Film and Video Art.

In the presence of Viktoria Metschl and Ahmed Assyad. With the support of Goethe-Institut Brussels.

——

Jocelyne Saab

“Once you hold a camera, you assert yourself through your profession. You react with your sensitivity as a woman — I don’t deny it. On the contrary … Maybe, in order to define it, although I can’t say for sure, maybe it’s about a gaze that lingers less on the surface of things, like that of cannons or armies. I always preferred to know the sensitivity of people in their details, the children, the women, the men, the daily life of human beings … In this field, people are so astonished to see a woman arriving that they make space for her and they respect her.”

Jocelyne Saab (1948-2019) was born and raised in Beirut. After completing her studies in economic sciences at the Sorbonne in Paris, Saab worked on a music program for the national Lebanese radio station before being invited by poet and artist Etel Adnan to work as a journalist. Unlike most war reporters, who must travel to war zones to pursue their profession, war came to Saab’s native Lebanon in 1975, and that same year saw the beginning of Saab’s filmmaking career with Lebanon in Torment, an account of the various forces and interests behind the incipient conflict. The war would last another 15 years, and Saab’s chronicling of its horrors — particularly in her remarkable “Beirut Trilogy”, comprising Beirut, Never Again (1976), Letter from Beirut (1978), and Beirut, My City (1982) — is unequalled in both its ethical integrity and emotional impact. The same candour and empathy Saab applied to the war in her homeland can be found in her other documentaries. Filming the struggle of the Polisario Front in the desert of Western Sahara, the consequences of the Infitah on Sadat’s policy in Egypt, or the aftermath of the Iranian revolution of 1979, a picture of a Middle East removed from reductive simplifications emerged through the polyhedral prism of her camera. “I believe that what makes up the specificity of my trajectory is that I have always wanted to remain coherent; I have always been ready to fight for what I believe in, to show and analyse this changing Middle East that I’m so passionate about. Yet the day came when I grew tired of it, or rather my eyes grew tired. I couldn’t see anything anymore — there had been too many deaths and too much suffering. I then moved on to fiction.” Her entry into fiction filmmaking came in 1981 when she worked as second unit director on Volker Schlöndorff ’s Circle of Deceit. Shortly after that, she directed her first fictional work, A Suspended Life (1985), set in the same war-torn Beirut she had documented ten years prior. After the war reconfigured the whole country, in Once Upon A Time in Beirut (1994), Saab tried to rescue the cinematographic memory of the Lebanese capital in the same year that cinema turned 100 years old. In 2005, she was censured and her life threatened for making Dunia, a film shot in Cairo about desire, pleasure and female sexuality in the context of Islam. Until her death in January 2019, Jocelyne Saab remained devoted to what she called her “two permanent obsessions: liberty and memory.”

Introduced by Ricardo Matos Cabo.

New digital scans produced as part of the research project “Imperfect Archives” (KASK / School of Arts). Copies courtesy of Association des Amis de Jocelyne Saab and CNC (Centre national du cinéma et de l’image animée)

Les femmes palestiniennes (Palestinian Women)

Jocelyne Saab, FR, LB, 1974, DCP, 12′

Palestinian women, the often-forgotten victims of the Israeli-Palestinian War, are here given a voice by Jocelyne Saab. Commissioned by Antenne 2, but never aired.

“I wanted to present images, of which there were very few then, of these women, Palestinian fighters in Syria. We are talking about just before Sadat’s visit to Israel, and therefore the situation was very tense. While I was editing the film in the offices of Antenne 2, Paul Nahon, then head of the foreign editorial department, grabbed me by the collar and threw me out of the editing room. Palestinian Women was put in the freezer and has never been shown on television.”

Arabic / French spoken, English subtitles. Digital restoration by Cinemateca Portuguesa.

Beyrouth, jamais plus (Beirut, Never Again)

Jocelyne Saab, FR, LB, 1976, 16mm, 25′

Gunfire and song mix with a poetic voice-over written by the Lebanese writer and painter Etel Adnan (who also wrote a text for Letter from Beirut) in what would become the first entry in Saab’s “Beirut Trilogy”, which searches for traces of life amid the bombed-out buildings and errant fires of a ghost city, where even the children have become soldiers, looters, and scavengers.

“This film marks a turning point. It’s a wandering drift through a destroyed Beirut. To express my sensitivity to a country that I love and that has been destroyed, I asked the Lebanese poet Etel Adnan to write the commentary. Our two sensibilities found one another. This commentary was surprising to many because it doesn’t respect the rules of reportage. It’s a poem expressing personal impressions that could be those of all Lebanese.”

Arabic / French spoken, English subtitles

Lettre de Beyrouth (Letter from Beirut)

Jocelyne Saab, FR, LB, 1978, video, 47′

Three years after the beginning of the civil war in Lebanon, Jocelyne Saab returns to a Beirut that has irrevocably changed, where she wanders the streets, rides buses, chats with refugees and peacekeepers, and reflects on the war’s toll during a brief moment of peace.

“I feel that a film should be able to envelop the spectators in the atmosphere. In Letter from Beirut, I wanted to show how abnormal things become normal. And I had recourse to a game of notations on the characters because I believe that, very often, the gestures of everyday life have more weight than political declarations.”

Arabic / French spoken, English subtitles

Les Enfants de la guerre (Children of War)

Jocelyne Saab, FR, LB, 1976, 16mm, 10′

Days after the massacre of Karantina, in a predominantly Muslim shanty town in Beirut, Jocelyne Saab met children who’d escaped, and who were deeply traumatised by the horrific fighting they’d seen with their own eyes. Saab gave the children crayons and encouraged them to draw while her camera turned. She made a bitter discovery: the only games the children engaged in were war games, and war would quickly become a way of life for them as well.

“Children of War denounces the violence that is inflicted on children of ten years old who can no longer speak, think or draw other than in terms of war: they mimic war.”

Arabic / French spoken, English subtitles. Print courtesy of Internationale Kurzfilmtage Oberhausen.

Madinat Al-Mawta (Egypt, City of the Dead)

Jocelyne Saab, FR, LB, 1977, 16mm, 37′

A portrait of the City of the Dead, an inhabited cemetery just outside of Cairo and on the fringes of the city’s public dumping ground, like a living reproach and a bad conscience. Starting from the City of the Dead, the film shows the populous neighborhoods of Cairo in the grip of hypertrophy and misery, every day more threatened by paralysis.

“I still ask myself how I was able to combine surrealism and social reality in this film. The great poet Ahmed Fouad Negm was then in prison, because the regime was displeased with his contestatory texts, and at the time one was imprisoned for no apparent reason. So, I followed his companion Azzam below the windows of the prison to pick up the poems Negm would throw through the bars of his cell. Cheikh Imam sang his poems to revolutionary students who gathered in the City of the Dead. It was exhilarating. We still believed we could change the world.”

Arabic / French spoken, English subtitles. Print courtesy of Cinémathèque Française.

Beyrouth, ma ville (Beirut, My City )

Jocelyne Saab, FR, LB, 1982, 16mm, 35′

Beirut, My City finds Saab and her collaborator, the playwright and director Roger Assaf, returning to the shell of her former home following Israel’s 1982 invasion, finding small glimmers of hope in the chaos of refugee camps and the rubble of decimated neighborhoods.

“I consider this to be my most important film, the one that is the closest to my heart. In 1982, my house was burning. That’s not nothing. It was a very old house. 150 years of history went up in flames and disappeared. All of that is suddenly destroyed. The family home, wiped off the map, gone from the city, having become a pile of ruins.”

Arabic / French spoken, English subtitles. Print courtesy of Cinémathèque Française.

——

Heiny Srour

“Those of us from the Third World have to reject the idea of film narration based on the nineteenth century bourgeois novel with its commitment to harmony. Our societies have been too lacerated and fractured by colonial power to fit into those neat scenarios. We have enormous gaps in our societies and film has to recognize this.”

Born in 1945 in Beirut, Heiny Srour studied Sociology at the French University of Beirut (Ecole Supérieure des Lettres) and went on to study Social Anthropology at the Sorbonne in Paris, where she was a student of both Marxist sociologist Maxime Rodinson and anthropologist filmmaker Jean Rouch. In 1969, while pursuing a PhD on the status of Lebanese and Arab women and working as a journalist for AfricAsia magazine, she discovered the struggle of the Popular Front for the Liberation of the Occupied Arabian Gulf, which led an uprising in the province of Dhofar against the British-backed Sultan of Oman. Determined to make a film about this feminist movement, she spent two years doing intensive research and finding the necessary funds before setting out to Dhofar. From the Yemeni border, Heiny Srour and her team crossed 500 miles of desert and mountains by foot, under bombardment by the British Royal Air Force, to reach the combat zone and record the only document shot deep inside the Liberated Area. The Hour of Liberation was completed in 1974 and selected at Cannes Film Festival, making Srour the first woman from the Third World to be selected at the prestigious international festival. Including four years of restoration, this documentary took, all in all, ten years of her life. It took her six years to achieve her next film, Leila and the Wolves (1984), in which she unveiled the hidden histories of women in struggle, in particular in Palestine and Lebanon, by weaving an aesthetically and politically ambitious tableau of history, folklore, myth and archival footage. In her words: “Why shouldn’t women be ambitious? Because men only want women to exclusively deal with women’s issues like home, family and so on, they want to ghettoize us. I resent this. We should deal with the public affairs and political issues too.” Since initiating a feminist study group in Lebanon in the early 1960s, Heiny Srour has been vocal about the position of women, in particular in Arab societies. She has written and spoken extensively about the image and role of women in Arab cinema. In 1978, along with Tunisian filmmaker Selma Baccar and Egyptian film historian Magda Wassef, she co-authored a manifesto ‘For the Self-Expression of the Arab Woman’, remaining passionately active in her feminist advocacy to this day. More recently, she shot a film in Vietnam (Rising Above: Women of Vietnam, 1995) and was the only filmmaker to film Egyptian protest singer Sheikh Imam in his home and neighbourhood (The Singing Sheikh, 1991).

In the presence of Heiny Srour

Saat El Tahrir Dakkat (The Hour of Liberation)

Heiny Srour, UK, FR, LB, 1974, DCP, 62′

“In the Arab world, it is the very first time that an organized political force considers the liberation of women as an end in itself and not only as a way to get rid of imperialism more rapidly. In the Arab world, it is the first time that practice goes as far as slogans.”

In the late 60s, Dhofar rose up against the British-backed Sultanate of Oman, in a democratic, feminist guerrilla movement. Heiny Srour and her team crossed 500 miles of desert and mountains by foot, under bombardment by the British Royal Air Force, to reach the conflict zone and capture this rare record of a now mostly-forgotten war. The People’s Liberation Army — barefoot, without rank or salary — freed a third of the territory, while undertaking a vast program of social reforms and infrastructure projects — schools, farms, hospitals, and roads were built, while illiterate teenage shepherdesses became more forceful feminists than Simone de Beauvoir or Germaine Greer, and 8-year-old school children learned to practice democracy with more maturity than so many adults. A still-topical portrait of a liberated society and an exploration of the role of oil in U.S. and British involvement in the Middle East, The Hour of Liberation Has Arrived was the first film by an Arab woman to screen at Cannes. (Film Forum)

Arabic spoken, English subtitles. Digital Restoration by Cinémathèque Française & CNC.

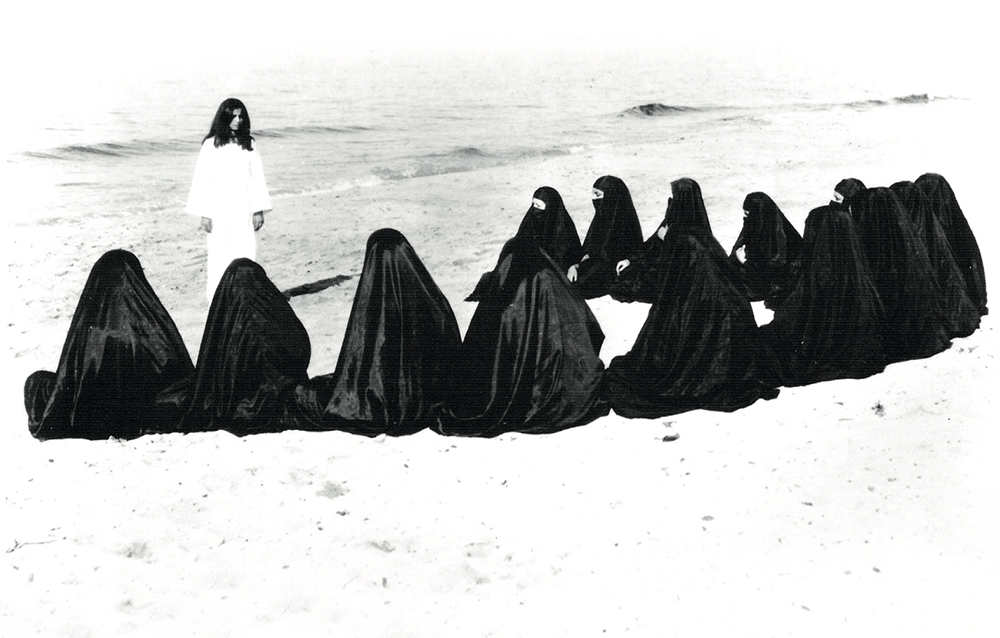

Leila wal Zi’ab (Leila and the Wolves)

Heiny Srour, UK, LB, 1984, DCP, 90′

“The visual leitmotiv of the film is Arab women sitting immobile under the high sun, while half-naked men bathe joyfully on the beach. Gradually, women will start getting impatient, as historic events go by, and they will move towards the water for a dip … but in the Middle-East, the dance of death still continues.”

A film which questions the gospels of the gun; its images flowing in search of woman’s political and historical identity in the Middle East … Throughout the film, an Arab woman wanders through real and imaginary landscapes of Lebanon and Palestine encountering voices from the peripheries of middle-Eastern politics: uncovering submerged yearnings and testaments of Arab women’s resilience. In her wanderings, she returns over and over again to Lebanon, the “jewel in the crown” of French colonial twilight states, a country in which crimes of honour took the lives of two women a week during the 70s. Yet Leila is not an anthropological journey but a survey of mythic and symbolical protest. Through her “eye” comes a search for political character in a Lebanon now permanently stained by the massacre of Sabra and Chatilla; caught in the throes of bitter civil war, Israel’s ‘backyard’. Leila prods these moments of loss and discovers ghosts of a very different life before the wolves. (John Akomfrah)

Arabic spoken, English subtitles. Digital Restoration by CNC. Selected for Venice Classics 2021.

——

Atteyat Al-Abnoudy

“I don’t want to be labelled a women’s filmmaker because I make films about life, and women are only a part of this life. I make films about people who I know, who I relate to (class-wise speaking) — humble and poor people. About their struggle to live, about their joy, and about their dreams. I still learn from them, from what they are doing and of their wisdom about life. I give the floor to my people to speak out. That is why they call me ‘the poor people’s filmmaker’.”

Atteyat Al-Abnoudy (1939-2018) was born Atteyat Awad Mahmoud Khalil into a family of labourers in a small village along the Nile Delta. A child of Nasserism, she studied law at the University of Cairo while supporting herself financially by working as an actress and assistant director at the theatre. At the beginning of the 1970s, she decided to study film at the Cairo Higher Institute of Cinema, where she created Horse of Mud, which was not only her first film but also Egypt’s first documentary produced by a woman. Her graceful focus on the disadvantaged and the unrepresented in Egyptian society would earn her the nickname “the poor people’s filmmaker,” but it also enkindled a confrontation with censorship. “The censors didn’t like to show the people as very poor after twenty years of revolution in Egypt. They think cinema, especially documentary, should be propaganda for the state. In a way, it’s the fault of the filmmakers who were making documentaries over the past twenty years. They made at least eleven films about the construction of the Aswan High Dam, but they spoke only about the machines, the tractors, the engineers. Nobody talked about the working people who died and suffered to help build this Dam.” Despite its limited circulation, Horse of Mud went on to win numerous international prizes, after which Al-Abnoudy made her graduation film, Sad Song of Touha, a portrait of Cairo’s street entertainers — which she created in collaboration with her husband, poet and songwriter Abdel Rahman Al-Abnoudy. She continued her studies at the International Film and Television School in London until 1976 and persisted to document the daily lives and struggles of economically and socially marginalized groups in Egypt, while exposing the structural inequalities within the socio-economic system. In films such as Permissible Dreams (1983) and Democracy Days (1996), she attended to the lot of Egyptian women, a choice of subject matter which has frequently invited the displeasure of government authorities. Against the grain, Atteyat Al-Abnoudy managed to produce more than thirty films which were shown worldwide, albeit rarely in her own country. Before her death in 2018, she left her film estate to the Cimatheque — Alternative Film Centre in Cairo, which continues to advocate her legacy of independent and committed filmmaking.

Copies and texts courtesy of Asmaa Yehia El-Taher, Yasmin Desouki and Cimatheque — Alternative Film Centre in Cairo

Husan al-Tin (Horse of Mud)

Atteyat Al-Abnoudy, EG, 1971, 16mm, 12′

In her first film, made on a shoestring with borrowed equipment, Atteyat Al-Abnoudy captures the basic process of mud-brick making on the banks of the Nile. The film was refused by the censors, who didn’t like to show the people as very poor after twenty years of revolution in Egypt. Eventually, they gave permission for non-commercial screenings, after which the film went on to win more than thirty international prizes.

“For the first time, the people talk about themselves, and we listen to their voices, not a cleverly written commentary on what the people are doing, like strangers coming from the sky, telling us what we are seeing now … The brick factory workers dominate the screen: their faces, their hands and their suffering … I worked on this 10-minute film for two years, because I had no money, and also because the bricks have to be dried in the sun. I shot the film at the end of the summer, and I had to wait till the next summer to complete it.”

Arabic spoken, English subtitles. Film prints courtesy of Arsenal – Institute for Film and Video Art.

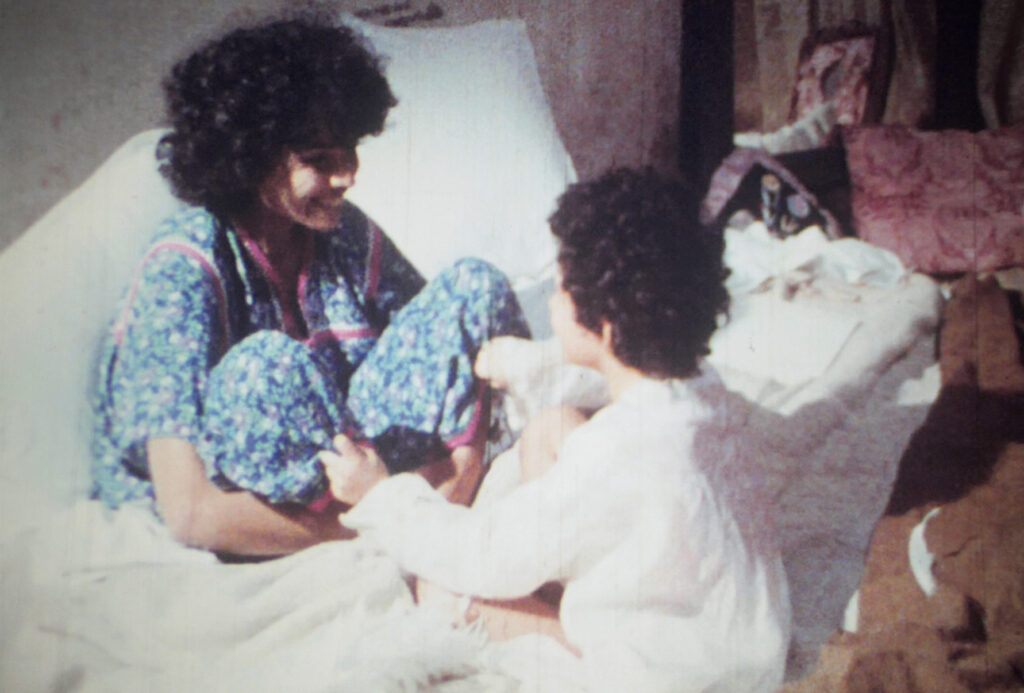

Ughniyat Touha al-Hazina (Sad Song of Touha)

Atteyat Al-Abnoudy, EG, 1972, 16mm, 12′

In many ways the sister film to Horse of Mud, Al-Abnoudy’s second film, her graduation film at the Film School in Cairo, is a portrait of Cairo’s street performers. The artistry of this community of fire-eaters, child contortionists, and other performers is captured through the lens of Al-Abnoudy’s unobtrusive camera, accompanied by the spare and haunting narration provided by poet Abdel Rahman Al-Abnoudy.

“I don’t want to make films because of some beautiful subject or because there’s something fascinating me in the colours or anything like that. We always tend to see lovely houses and lovely hills, the decor and other fantastic things before us on the screen. But the poor people and the working class are not on the screen, when they have the right to be. When I talked to the young belly-dancer in Sad Song of Touha, for instance, she said she really would like to be a dancer in a cabaret, because she always goes to the cinema and sees these belly-dancers and beautiful girls. She said, ‘I would like to see myself on the screen.’ So I said, ‘why not!’”

Arabic spoken, English subtitles. Film prints courtesy of Arsenal – Institute for Film and Video Art.

Al-Sandawich (The Sandwich)

Atteyat Al-Abnoudy, EG, 1975, video, 12′

The Sandwich explores the daily life and work of children in Abnoud, a rural village located 600 kilometres to the south of Cairo, where the trains that carry the tourists to the south of Egypt pass through without stopping. A boy outsmarts the meagerness of his circumstances by dripping goat’s milk on a piece of stale bread and turning it into a special sandwich.

“I believe film is a language I can use to say many things, a poem, a short story. I once made a film without a single word in it about one day in the life of children in the village of Abnoud. At lunch, you know, they take their bread and go to the cow’s udder for milk, just to have something on the bread! That’s how poor they are.”

Arabic spoken, English subtitles

Bihar al-’Attash (Seas of Thirst)

Atteyat Al-Abnoudy, EG, 1980, video, 44′

In Seas of Thirst, Al-Abnoudy moves away from her usual exploration of Egypt’s south to the north of the country, wherein she captures communities living near the salty lakes of El Borrolos during a treacherous drought. Bearing a stark contrast to the barren landscape around them, the richness of the local characters provides the moving narrative of a struggling class in its entirety.

“As a human being, one can learn a great deal about people when working on a documentary film. I learned to wait for others and not have them wait for me. Watching the young girls and women carry tens of bricks on their heads passing before the camera one after the other, I considered capturing them from different angles but immediately stopped myself. I felt it was a form of injustice to exploit the labor of others as it happened before me for the sake of filmic content. I learned to respect them, to respect their presence, and to ensure that the camera is always brought to their level.”

Arabic spoken, English subtitles

Al-Ahlam al-Mumkinna (Permissible Dreams)

Atteyat Al-Abnoudy, EG, 1983, video, 31′

Permissible Dreams traces the life of Oum Said, a woman farmer living in a small town on the Suez Canal. Although she does not read or write, the woman in question is her family’s economist, doctor, and the planner of its future, as she dreams “to the limits of her possibilities”. This film, capturing a woman’s struggles with societal and gender inequality, was part of the German-produced series As Women See It.

“All I ask of the image is not to create an opacity between the character and what she wants to say. There is a degree of pain that cannot be transmitted. We only have a reflection of his pain. But we touch a degree of dignity, pride and wisdom. You must know how to reveal reality with its dark and luminous sides, without hiding an admiration for the total commitment of the beings whose lives meet History.”

Arabic spoken, English subtitles

Iqa’ al-Haya (Rhythm of Life)

Atteyat Al-Abnoudy, EG, 1988, video, 60′

A pivotal and rather innovative work in Al-Abnoudy’s career, Rhythm of Life can be seen as a kind of symphony depicting rural life as played out in four acts. A beautiful depiction of the daily life of farmers, the film unfolds in the filmmaker’s characteristically unobtrusive and deeply humane manner.

“For a long time already, I had it in mind to make this very big project describing the daily life of the Egyptian people. I try to play on contradictions, and I think I have something to say within the documentary form, a way of bringing to it a sense of narrative — a dramatic way of showing life. I try to re-arrange reality in an artistic way.”

Arabic spoken, English subtitles