“The great creator is the great eraser”

Steward Brand (Long Now foundation)

As always, I’m involved in a few different projects right now. One of them is the compilation and editing of a (Dutch only) reader on ‘Cinema in Transit’, consisting of a few essays describing and reflecting on current transitions in the world of cinema, taking in account the expansion of cinema over countless media, technologies and modalities, the fragmentation and individualisation of the cinematic experience and the digital image replacing the analogue one. Another project is titled BOM-Vl. (an acronym which stand for something loosely translated as “preservation and disclosure of multimedia archives in Flanders” – yeah, governement funded projects tend to have expensive titles), a quite prestigious project that involves the local broadcasting industry (in the driver’s seat, of course), several universities and cultural organisations, who are trying to figure out a way to digitalise and archive all their data via a communal platform. Slightly Utopian? You bet. One of the elements that, for me, tie together these two projects, is the issue of the digital access of audiovisual archives, and the question whether “film” (so I’m not talking about digital-born content here, but film, with all it’s material and technical characteristics) can (or should) actually be digitalised to match its ‘look & feel’.

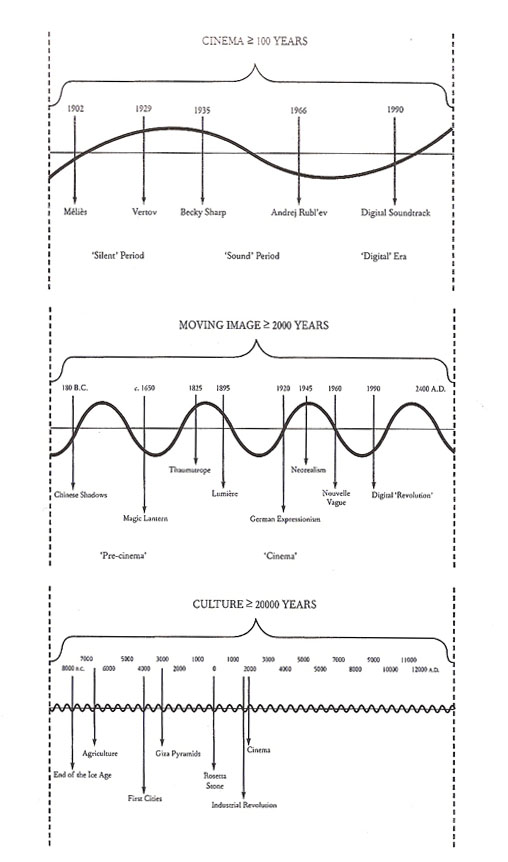

Since quite a few years we have all been enveloped in the rhetoric of the so-called digital revolution, promising a brave new world of media, and the moving image not in the least. While most of us celebrate the immense potential of this techno-social shift (see the Video Vortex category on this blog, a.o), we are forgetting about the things we are loosing in the process. One of the things that is fading away is the (traditional) cinema experience, which is really a way, an art perhaps, of seeing the world. Now it seems that celluloid is doomed, and that experiencing the moving image has become something completely different for a whole new generation out there, enjoying cinema when-ever, where-ever, on their iPod or portable phone, on the bus and in the bathroom, what’s becoming of the photochemical cinema, and the places that show, nurture and feed it? Will all of this be a folklore phenomenon soon?

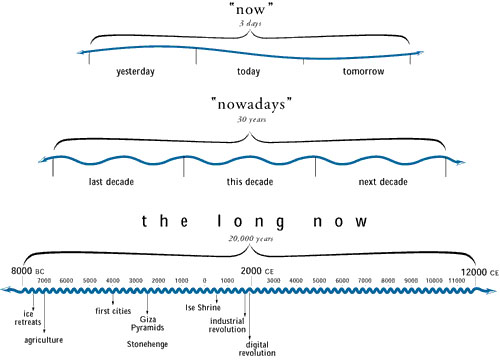

One of the people who tackles these questions, in a provocative way, is Paolo Cherchi Usai, who’s the Director of the National Screen and Sound Archive in Australia right now and published, a.o., the inspiring book ‘The Death of Cinema’, which is, as Martin Scorsese notes in the introduction “an elegy to the thousands copies of films being destroyed every day, all over the world…” and “a portrait of a culture ignoring the loss of its own image (…) a devastating moral tale, the recognition that there is something very wrong with the way we are taught to disregard the art of seeing as something ephemeral and negligible.” The subtitle of the book is “History, Cultural Memory and the Digital Dark Age”, which is derived from the The Clock of the Long Now (01999), a wonderful project of Steward Brand of the Long Now foundation, who seek to “promote ‘slower/better’ thinking and to foster creativity in the framework of the next 10,000 years”. The Clock of the Long Now is one of the projects that provokes us to think outside of time, extending the idea of the length of the future that we think about. It’s a monumental-scale 10,000 year clock that is intended to ‘tick’ once every year, ‘chime’ every 100 years, and ‘cuckoo’ every 1000 years. The Long Now intends to situate the monument in an artificial cave, built within a mountain range in the Nevada desert. Btw: another member of the Long Now is the great Brian Eno, who has always been interested in he experience of time and the idea of the eternal present, something that can be heard in some of his albums he made since the 1970’s, in which he developped sonic landscape as extended present tense, music that expressed “the Long Now” and “the Big Here” (remember ‘Music for Airports’?).

Cherchi Usai, like the people of the Long Now, points to the fact that we we’ve lost the ability of thinking long term, now that time has been sliced into ever finer parts, and there seems to be an ever-decreasing horizon into the future, with very little encouragement to lay long term plans, not in corporations, not in the government… and even in education and the cultural world we are only looking as far as the next quarterly results, the next public project, the next exhibition, the next opportunity “to score”. Cherchi Usai ultimately want to question this “self-perpetuating wave of cultural fundamentalism”, especially when it comes to cinema, where digitalisation quickly has become a pervasive ideology (as everywhere). “Why”, he asks, “is our culture so keen in accepting the questionable benefits of digital technology as the vehicle for a new sense of history?”

So we’re very happy Paolo is willing to publish one of his recent writings in the ‘Cinema in Transit’ publication (in Dutch) – and it’s a text that deals in a very critical way with the matters which I’m supposed to “research” for the BOM project. Titled “Four Unsatisfactory Answers to the Question of Digital Access” (it is an early draft version of an essay which will be included in the forthcoming book Film ‘Curatorship: Archives, Museums, and the Digital Marketplace’, co-edited by Usai with David Francis, Alexander Horwath and Michael Loebenstein (Vienna: Synema – Gesellschaft für Film und Medien / Österreichisches Filmmuseum, 2008)), the essay structures the popular perception of the digitalisation of film against the concrete work of the filmarchivist (or curator), constantly dealing with a complex web of factors including market value, aesthetic value, history, public funding etc.. One could read his writings as the product of bitter nostalgia easily, I guess, but here is someone with a genuine love of cinema, dealing on a day-to-day basis with the decay of the things he cherishes, and honestly, working with people who can’t wait to transfer our audiovisual heritage into bits and bytes, no matter what, to exploit via Video-on-Demand and what not (although I understand their concerns), this is a voice that I want to hear, a necessary voice. As he writes: “In practice, the commercial world is already within our gates, and it has been within our gates for quite some time. This is no longer a matter of whether or not we want to deal with it; it is a matter of how we can we deal with it without betraying our cultural mission.(…) Digital access” is the name of the game, now and in the foreseeable future; we all know that, but the word “digital access” is embedded with a whole array of philosophical, ethical and strategic questions. How will “digital access” change the way we look at film or we listen to a sound recording in an archive or a museum? And how are we going to explain the history of projection and recorded sound in the digital age, and still protect our own integrity as archivists and curators?”

These are valuable questions to be integrated in the debate, questions that we have to try to work out, before we get trapped in an impossible choice: preserve or show? Because, face it, who will want to pay for the continuous work of audiovisual archives (in the traditional, object-oriented meaning) if everything is commercially available via the internet, in a nice digital package, in different formats to suit all your needs?

“The future is process, not a destination.”

Bruce Sterling