”Trying to control music sharing – by shutting down P2P sites or MP3 blogs or BitTorrent or whatever other technology comes along – is like trying to control an affair of the heart. Nothing will stop it.”

(Thurston Moore, adapted from an article in the book ‘Mix Tape: The Art of Cassette Culture’, 2005)

Looks like Radiohead’s stunt, releasing ‘In Rainbows’ online for free, was an eye-opener for quite a few people in the music biz. In their footsteps some other “household” names in the world of popular music have recently published their music for nada: The Charlatans, back from the dead, have released their new album via the servers of Radio Station Xfm. The Verve, also freshly reformed (do I see a pattern arise? No, Axl Rose, no!), teamed up with NME.com to give away a 14-minute jam from their first session back in the recording studio. And Trent Reznor, no longer constrained by a record label, uploaded part one of Nine Inch Nails’ new four part (sigh..) album ‘Ghosts I-IV’ to several BitTorrent sites. The other parts can be bought via their website. Reznor did a similar experiment with the latest Saul Williams album, on which he collaborated. Williams, never one to mince words, explained this choice as a way to get rid of the middlemen: “Each label, like apartheid, multiplies us by our divide and whips us ’til we conform to lesser figures. What falls between the cracks is a pile of records stacked to the heights of talents hidden from the sun. Yet the energy they put into popularizing smut makes a star of a shiny polished gun. … The ways of middlemen proves to be just a passing trend. … And when you click the link below, i think it fair that you should know that your purchase will make middlemen much poorer…”.

Although this project had obvious similarities with the Radiohead experiment (free low quality with the option of buying a higher-quality digital download), the lack of an obsessive fan-base has certainly made a difference: just 28,322 of the 154,449 people who downloaded Williams’ album before January 2008 chose to pay ($5). At the same time though, that’s nearly as many as who bought Williams’ previous traditional release and far more who are hearing his music – which will probably translate to increased concert ticket and merchandise sales, which was the basic goal anyway (“to set the stage for me to perform in the way I like to perform and maybe get more people at a show than I normally would”). Furthermore, by cutting out the “middlemen” Williams is likely taking a much larger cut of the download revenue than they would receive of CD sales revenue.

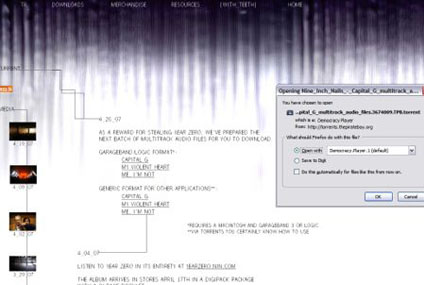

But how far do these experiments go, really? Radiohead shut down its download section in December, as did Williams (but of course, the mp3’s remain available illegaly on most P2P networks). Are these just one-off strategies, aimed at exploiting novelty factor and marketing value? After all, didn’t Prince, who released his ‘Planet Earth’ for free with The Mail On Sunday last summer, reach more people than the he did with his previous releases – with 21 sold-out concerts in Brittain as a nice extra? And didn’t these stunts generate loads of media attention (while diverting the attention away from the music itself, in some cases for the better perhaps)? But how long before the novelty value wears off? The Radiohead people already let us know that it’s improbable that they will publish their music in the same way again. Does that mean they go back to more traditional models (since they have an agreement with the XL label now), or that they are willing to dig further in the dynamics of network culture? Anyways, the latest NIN stunt prooves that the trick still works: soon after the release ‘Ghosts’ has grown out to be the most downloaded torrent at The Pirate Bay, and the $5 entire download version has shot up to the #1 spot on the sales charts of Amazon. And for the hardcore fans (boys and their toys) there’s always the double CD version or the “deluxe” package with CD, DVD, and Blu-Ray copies, and even a “ultra-deluxe” edition that also includes vinyl copies and signed “art” prints ($300!!) – apparently, It took just over a day for that package to completely sell out, earning Reznor $750,000 in revenue from just that option alone…

Also, the availability of free music via the net has proven to be a indispensable way of creating and reaching a fanbase – see f.e. the internet-based hypes like Clap Your Hands Say Yeah. The most cited example in this context being the one of Wilco, who after being dropped from Reprise Records in 2001 over creative conflicts, made ‘Yankee Hotel Foxtrot’ available for free, which was picked up by enthousiastic listeners worldwide, got subsequently releases on Nonesuch (ironically, also a sublabel of Warner, like Reprise) and reached higher on the charts than any of their prior releases. They later tried new internet forays, like the first-ever MPEG-4 webcast with Apple, as well as more free online offerings, made a documentary partly funded by online donations, and are now one of the most celebrated (by critics and audience alike) popular bands. Wilco’s Jeff Tweedy in an interview with Lawrence Lessig, april 2005: “Music is different from other intellectual property. Not Karl Marx different – this isn’t latent communism. But neither is it just a piece of plastic or a loaf of bread (…) We are just troubadours. The audience is our collaborator. We should be encouraging their collaboration, not treating them like thieves.”

Other experiments are interesting as well: Einsturzende Neubauten has their neubauten.org supporter project, an attempt to continue producing music through online support of fans, who for a financial contribution, get loads of exclusive stuff: not only CD’s and DVD’s, but also webcasts which provide insight in “the working process of the band at rehearsals and recording”. ArtistShare provides a service for musicians to fund their projects outside the normal recording industry, utilizing micropayments to allow the general public to directly finance, and in some cases gain access to extra material. Furthermore, the ‘honor system’, used in the Open Source communities, has been tried out by several musicians, like Juliana Hatfield. Of course, all these ideas have been discussed before, as far as in 1983, when Frank Zappa published the article ‘A proposal for a system to replace ordinary record merchandizing’, in which he wrote about the nonsense of the traditional mechanisms of the music industry (“Ordinary phonograph record merchandising as it exists today is a stupid process which concerns itself essentially with pieces of plastic, wrapped in pieces of cardboard”) and the “positive aspects of a negative trend – hometaping”.

But what Zappa couldn’t predict was the way people deal with music has fundamentally changed. In Marshall Kirkpatrick’s article ‘Is it Time to Declare Music Downloads a Loss Leader?’ he quotes somebody “close to the business”: “Value is ascribed to things that people covet- at one point people coveted what they downloaded. They still do to some extent (ie, dimeadozen and the bootleg market, which is a nice self regulating distribution system) but with rapid adoption of one behavior, the commodity behind it shifts and goes toward ubiquity, ie free. You just have to shift what people will covet. It’s the same way with books, newspapers, TV, movies, memory, CPU, etc – every free market system follows this path. Intellectual capital complicates it but can also provide more impetus to be innovative.” The Intellectual Rights system as we know it sure is a “complication”, one that is being challenged more and more. Creative Commons offers an alternative, albeit not fundamental, and is being explored by projects like Opsound (“a gift economy in action, an experiment in applying the model of free software to music”) and musicians like Reznor, who released his ‘Ghost’ album with a CC license (free for non-commercial use), and recently also distributed multitrack versions of some pieces, incouraging appropriations and remixes. Brian Eno and David Byrne made a similar geste with some tracks of the remastered classic ‘My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts’.

So it looks like almost everyone agrees that 1. contemporary standards of what constitutes (monetary) value or fairness in music consumption have changed and 2. that the Sharing & Sampling Culture is here to stay = so there has to be a shift towards new business models, at least for those who really choose to make a living out of creating music (I have to say, some of the musicians I know couldn’t care less). Lots of musicians are starting to think and act outside of the industry models, taking in control production and distribution, and are realising that relatively more revenue has to be made from playing gigs (although there’s, at least where the big money is, also an industry involved, with quite a few “middlemen” in the way – cfr. Clear Channel) and merchandise sales (aren’t we still here to spend, spend, spend?), and hell, if that doesn’t add up, one can always start to maneuver into Hollywood (look what ‘Juno”s success did for Kimya Dawson), commercials (So, how did YOU get to know Jose Gonzales? And what the hell, good old Bawb gave in too, didn’t he?) or even the contemporary art world, where’s there’s still money to be made by making “sound art” (what’s in a name?) installations, suitable for museum halls, walls and elevators, and selling silly priced limited-edition copies, dressed up as desirable “art” objects, creating artificial scarcity for maximum profitability (well, it did Trent some good too). Nowadays, where’s the shame in that, huh? Where is the shame?