A small text I wrote (originally in Dutch) for Kunstenfestivaldesarts 2020 to accompany Wang Bing’s work Scenes: Glimpses From a Lockdown.

“You shouldn’t be here, Sir.” These are the words that can be heard spoken in a foreign language at the start of Scenes, Wang Bing’s new installation. The admonishment seems to be addressed off-camera to the film-maker as he points his camera at a huge throng of oil lorries that seem to be furloughed in the green suburb of an as yet unknown city. Is it a coincidence that Wang Bing has given this scene – in which attention is exceptionally drawn to himself – such an important place? After all, Scenes is the result of his first cinematographic foray outside his homeland of China: this is Lagos, the most populous city in Nigeria and, by extension, on the African continent.

But this is not the first time that the film-maker has been in places where according to the rules he “shouldn’t be”. Two decades ago as a recent graduate in photography and art, he travelled to the heart of the condemned industrial district of Tiexi, in north-east China. Without official permission, he spent two years here filming the maze of factory buildings and the living spaces that went with them. Using a rented DV camera, he managed to distinctively record the precarious lives of the remaining workers who were facing the slow deterioration of their living environment and job security. Using more than three hundred hours of footage, he created the monumental Tie Xi Qu/West of the Tracks (2002), a nine-hour documentary on China’s transition from an industry-based controlled economy to a consumption-based market economy, and on the ensuing erosion of the collective working class that has inexorably given way to the rise in cheap and temporary labour.

Ever since, Wang Bing has tirelessly focused on unjust and commonplace experiences in everyday life that is stifled all too often by the success of China’s “miracle of growth”. In a small mountain village in the province of Yunnan, he produced a portrait of three young sisters (San Zimei/Three Sisters, 2012) who had to look after themselves when their parents left to work in far-off cities – unfortunately something that is happening to tens of millions of children in China. In Ku Qian/Bitter Money (2016), he followed three young people leaving their village to look for work in the city of Huzhou in the east of the country, known for its huge temporary workforce. In this film and others, Wang Bing patiently takes stock of the impoverished material and social circumstances of migrant workers who are principally rural and cannot claim urban citizenship. This means that over a tenth of Chinese nationals are considered undocumented foreigners in their own country. From urban workshops where these “second-zone citizens” slave away for hours for a tiny wage and are painfully aware of what is commonly called “bitter money” to a remote psychiatric institution where mentally ill patients and political renegades are left to their fate (Feng ai / ‘Til Madness Do Us Part, 2013) or refugee camps where members of the Ta’ang, a Burmese ethnic minority, are trapped between violent civil war and the Chinese border (Ta’ang, 2016): in the internal geography of Wang Bing’s work, the uncertain lives of those who on the margins of society, in the middle of vast and rapidly changing landscapes in 21st-century China, are central.

Is it really such a great leap to Africa? Under the banner of the historical friendship forged between China and Africa since the post-colonial peak of the Non-Aligned Movement, exchanges between the two regions have actually developed a great deal in the last two decades, an evolution watched with attention on the world’s economic and geopolitical stage. While China likes to boast investments and large-scale infrastructure projects that in its view will result in a “win-win” situation, accusations of neo-colonialism are increasingly being made. As Lamido Sanusi, the former governor of the Central Bank of Nigeria, wrote: “China takes our primary goods and sells us manufactured ones. This was also the essence of colonialism.” Yet the discussion about whether China is positioning itself as a colonising power or as a capitalist benefactor transcends a social and intercultural reality that is undergoing a complete transformation and poses huge challenges to both sides. The policy of China’s presence in Africa not only involves capital and goods, but the labour force as well, as reflected in the growing number of construction workers, road builders and shopkeepers in the socioeconomic fabric. Meanwhile, since the economic liberalisation of the 1990s, numerous African students and entrepreneurs have been trying their luck in major Chinese cities. This is especially the case in Guangzhou, a megacity in the south of the Pearl River Delta and one of the most populous regions in the world, which has become a retail industry hub between the economic superpower and several African states.

One of these shopkeepers is the central character in Scenes. Wang Bing met Kingsley in Guangzhou where he has a hairdressing business and buys merchandise for the shop he and his wife run in the Ikotun district of Lagos. This fortuitous encounter – something that continually drives his work – ultimately took Wang Bing to Africa in autumn 2019, a journey he had been waiting for for a number of years. The filming he did in Lagos provided the source material for a first version of the installation, which was part of the “China ⇋ Africa” exhibition at the Pompidou Centre in Paris. It shows fragments of Wang Bing’s first impressions of the African metropolis, from the agriculture and accumulation of rubbish on the outskirts to the retail outlets and carpool services in the centres. The Chinese presence is implicit in references to two of the main Chinese economic activities in Nigeria: oil extraction and mining. This happens to chime with Wang Bing’s previous investigations into the Chinese energy industry, Caiyou riji/Crude Oil (2008) and Tong dao/Coal Money (2009). However, it is also manifested in the thousands of motorcycle couriers whose bright green kit contrasts with the mostly drab urban landscape, not that different from similar services in Chinese cities. The courier service is also one of the visible traces of China’s recent entry on the African e-commerce and fintech landscape because the company in question aspires to be a multifunctional digital platform. Or how the flow of Chinese capital is gradually opening up a route into African online lives.

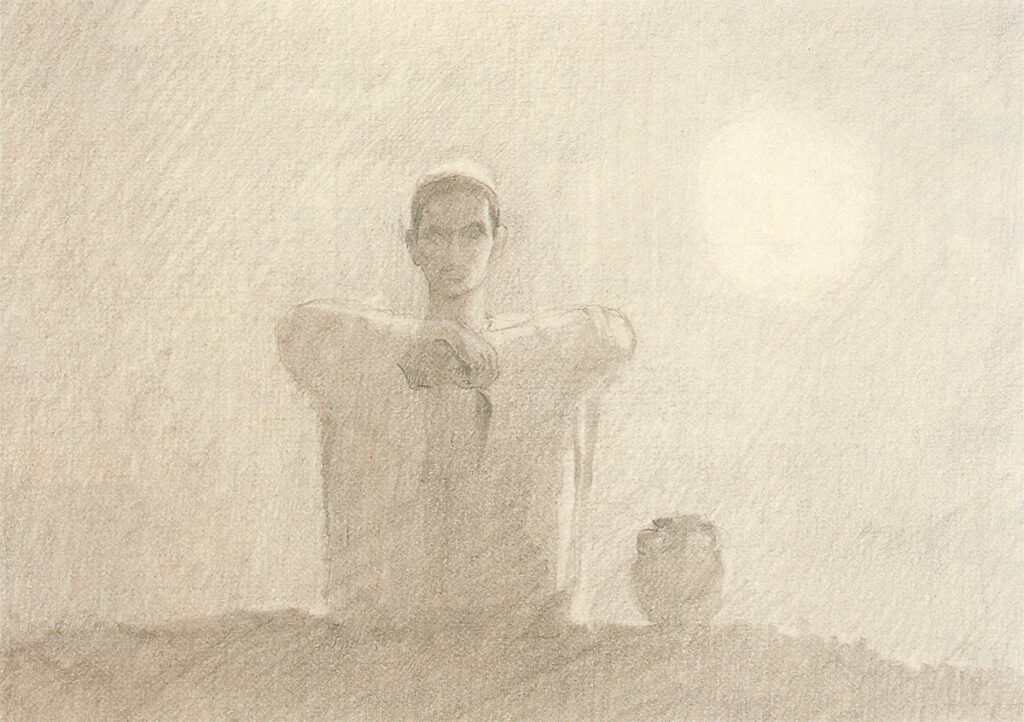

As China soaks up Africa’s natural resources, African states are importing huge quantities of cheap consumer goods bearing the label “Made in China”. It is goods like these that Kingsley and his wife stock in their shop, which seems to have been built in haste and where everything feels provisional. Wang Bing follows the couple and their young son as they roam through the packed network of streets and alleys in Ikotun, amid the multi-level tangle of modest stalls and narrow passageways of which their shop is part. He knows how to move his handheld camera in confined spaces like no one else, constantly adapting to the environment, always maintaining the right distance from people. He takes the time to observe their daily activity at length, a temporality that confers on them an existence on screen that transcends short-sighted clichés. It is in this constant scanning that Wang Bing manages to lose the negative connotations so often associated with filming in places where people say “you shouldn’t be”. That his work shows no hint of bleak voyeurism is down to his intense focus on what is in front of the lens, without claiming to know or understand in advance what should be seen. He does not take the position of someone who knows, but of someone who chooses to look, constantly lying in wait for something unexpected, for what cannot be captured in all-knowing frames. It is an approach that respects the visible dimensions of injustice and at the same time is radically opposed to the basic injustice that condemns “wretched of the earth” to invisibility or stigmatisation. Rather than trapping them in a context that is supposed to match their life, Wang Bing endeavours to achieve visibility that is open to glimmers of what might be possible.

Wang Bing’s installation in progress promises to become a diptych, with one part of it recorded in Lagos and the other part in Guangzhou. Meanwhile, the pandemic has not only postponed Kingsley’s planned trip back to China, but has also exacerbated the discrimination migrants face, whether they originally come from rural China or Africa. The draconian campaign to prevent the spread of the virus has hugely stigmatised them as high-risk populations, with the consequence that many have lost their homes and are deprived of any form of service. While inequalities in housing, healthcare, education, employment and security of residence continue to grow, migrant workers risk even greater precariousness. Wang Bing, who returned to Guangzhou in late April to continue filming, will doubtless not have missed these terrible developments. The tireless chronicler of the underside of the Chinese economic myth persists in focusing on the precarious lives that are generally condemned to obscurity. A task that authoritarian voices who stipulate where “you should or shouldn’t be” are too swift to ignore.