By John Akomfrah

Originally published in PIX 2 (January 1997, edited by Ilona Halberstadt, distributed by BFI, London). Republished by Tate Film on the occasion of ‘A Cinema of Songs and People’, curated by The Otolith Collective. Anand Patwardhan will be our guest for the next DISSENT ! session, on 8 November. John Akomfrah will be our guest on 20 and 21 November.

Anand Patwardhan occupies a unique place in documentary filmmaking. Very few documentarists are accepted as auteurs; among those, few are both directors and technicians; and from this elite corps, even fewer come from the so called Third World. Over the last twenty years Anand has consistently taken strands from different documentary filmmaking practices – the Cuban and Latin American Imperfect Cinema style; the more self-reflective political documentaries of Chris Maker and the Dziga Vertov group; the lyricism and attention to detail of the ethnographic school – and put them to work on a series of stunning documentaries.

From Bombay Our City to Father, Son and Holy War, his films have dealt with some of the key questions of our age – the ubiquity of difference in modern lives; masculinity as a source of conflict and power; the absurdities of political power. Except for his first two documentaries, his subject-matter has come from successive political crises in India : the Emergency; the rise of fundamentalism and communalism; the growing political polarisation. He has been holding a mirror to the Indian psyche, to see how it reflects questions of class-belonging, gender and political voice. It is unusual for a documentary film-maker of his caliber to have spent so much time and energy working on what are essentially local questions. The questions acquire an immediacy by being intensely regional in their raison d’etre and their outcome. Paradoxically, by interrogating the local questions over and over again, he has not only arrived at a refined vision of the state of play in Indian culture and society in the nineties, but also in the world at large – forms of fragmentation, the growing alarm with which people protect their ‘identities’, emerging forms of power – all are prefigured in his work.

These are films driven as much by absences as they are by presences. What is absent are agendas imposed rigidly on people, politics or places. Instead, the films are fixed by interests pursued relentlessly, selflessly, ethically. In Patwardhan’s films there is always a sense that what we are watching is a product of an inquisitive impulse – a search for answers through what people say and how they say it, the rhythms of the everyday, the gestures and actions of individuals.

Nowhere is his interest in the absence/presence dichotomy used to more effect than in Bombay Out City. In this film he investigates the relation between the culture and life which goes with being an affluent Bombay-dweller and what you do when you are poor in Bombay – what streets you sleep on. The relation between absence and presence is made tangible. Patwardhan interviews a lot of slum dwellers who feel that their condition is not natural – that the reason why they are in that position is because of someone’s neglect, incompetence, or the willful manipulation of their life chances. In this way the rich are evoked as a ghostly presence and their traces are etched deeper as the interviews are intercut with images of facades, the rich going about their daily business.

All his films deal with events which over time acquire political and cultural significance. But there is also the question of aesthetics which is rarely commented on – when people look for aesthetic insights they rarely turn to political documentaries. And yet the way in which Patwardhan investigates the complex relationship between figure and ground – the way he places people in the frame and the space he gives them to express themselves, merit special scrutiny. Through this scrutiny we discover a sustained attempt to think through the ways in which people construct oppressive political languages and motifs for resistance.

We also begin to see the complex aesthetic and formal questions raised by the attempt to provide the narrative for political activity; the attempt to release events in India from the confines of the stereotype. Central to this deconstructive gesture in his films is the question of repetition. In the repetition of motifs, one glimpses the dark power that images, symbols and motifs acquire in the lives of people. In Father, Son and Holy War, the colour orange signals the Shiv Sena’s public rallies and speech-making. Gradually this colour comes to stand for the circulation of notions of ‘purity’ and ‘impurity’. The process by which the film effects this marriage of political extremism and a particular colour is very complex and yet one is struck in the end by how effortless the whole thing seems.

In Patwardhan’s films symbols and icons are both a source of strength and a site of conflict. In Memory of Friends is not simply a biography of a Sikh Marxist who died fifty years ago, but is also about the way in which a number of conflicting groups – the State, Sikh Fundamentalists and fighters for communal harmony – fight over the symbol of Bhagat Singh as a political figurehead in contemporary India. In the film, photographs of Bhagat Singh, both in turban and deracinated, European clothes, are among the images which give clues to the uses and abuses of history. So what starts off looking like a hagiographic exercise on one political symbol from the Indian past becomes a complex film about how people empower themselves and the role icons play in that process.

Part of the attraction of the films lies in the fact that Patwardhan lives those events as a filmmaker. He practices what he preaches – a politics of tolerance. In a period of extreme political intolerance, in which a certain kind of politics exists simply to delegitimise other people and their right to be part of the State, the filmmaker enters, willing to confer on all the social actors the same respect. He goes in prepared to listen to people as individuals and they acquire their status as villains – or heroes – after the fact, because of what they say and do. All the films are narratives about Indians talking, or in some cases not talking but killing one another. But crucially they are about their actions, gestures and rhetoric. He observes the everyday, the unfolding fabric of Indian life as a discreet set of activities before these acquire the status of events. He is not interested in stories, but rather in the fragments which make up the story and the role that particular individuals play in it.

In his films we not only see events acquire the status of the real but get an insight into the complicated process of selection via which particular events attain the definitive status of the real; an insight into the convoluted process of legitimation through which patterns of extreme behaviour become the norm; the Indian reality, condition and fate. Along the way, a few of the mystifying and patronizing platitudes on India – its piety, its fatalism, its extremism – are shown to be ever-evolving historical dramas with living social actors, fragments from a mosaic lived and constructed by social groups.

In In Memory of Friends, there’s a man who is a minor player when Patwardhan first meets him – he does not have written on his forehead: “Hero – this man will save the day.” But in the process of observing, filming and interviewing him, it becomes clear to Patwardhan; and therefore to us, that this man has the right ideological and emotional make-up to provide a solid centre for the film. So gradually he gravitates towards him. It is as if he was there to watch this man make up his mind to stand against extremism. This may explain Patwardhan’s fascination with documentary: its privileged rendezvous with history; its uncanny prophetic power; it’s ability to give us an insight into the connections between actions and consequences. In the best documentaries we always glimpse the future. Take a look at Father, Son and Holy War and you’ll see my point.

Documentary film-making at its best – Flaherty, Rouch – is a complicated interrogation of reality. The quest to undermine cultural and political assumptions is central, particularly, the stultifying claims of the stereotypical, the cliché-ridden, the teleological. They are supreme acts of deconstruction. They do not try to replace an ossified image of a more real India. Rather, they work with and through the conventional images by seizing hold of them as frames and exploring how their reality is both manufactured and lived.

Let us take the assault on the mosque in Ayodhya. It was widely monitored by the media and people thought: how terrible, those fanatics in India, they are always doing things like that. But in the film [In the Name of God], we watch young men going on a march before they become the mob that tears down a mosque. You hear their opinions and so you follow a trajectory of rage which leads to the outcome. However, we are made aware that many options were jostling to become reality; we get to understand how this option (a mob will attack a mosque ) becomes the logical recourse in a perverse chain of reasoning. In another incident, the central figure in In Memory of Friends was killed by fundamentalists after the film was made. I was all the more shocked because in the course of watching the film I felt that the circumstances which led to his death were not a foregone conclusion; that reality is open-ended. Ultimately this is the value of Patwardhan’s films. They remind us that reality is a many-headed beast – wrestling with it requires both courage and flair.

Interview with Anand Patwardhan

By John Akomfrah and Ilona Halberstadt

Originally published in PIX 2 (January 1997, edited by Ilona Halberstadt, distributed by BFI, London).

John: Within the range of independent Indian work disseminated and discussed here, films by Mrinal Sen, Satyajit Ray etc. there seems to be a different assumption about your work. Namely, that because it is politically engaged the questions it raises are so transparent that one could almost forget that it was the product of film-making. Your films don’t seem to be discussed in relation to the artistic medium.

Anand: No, those questions never get asked anywhere. It’s as if the film-making is invisible although there’s no attempt on my part to hide the camera or the processes of filming. But I take it as a compliment that people are drawn into the subject matter directly and are not conscious of how the film is being constructed.

John: So let’s talk about that for a change. You do your own camera as well as the editing. As far as I know there are only two or three international documentary makers – Molly Dineen, Dennis O’Rourke – who also directly control the frame by doing the camera work.

Anand : I think the main reason I do camera is that the films are unpremeditated. They have a very long gestation period. If I was doing a shoot which was well organised and over a short period of time, then I could afford to have a cameraperson. As it is, by the fourth film I became the cameraperson out of necessity, but I began to like it. I began to feel impatient when I did have a cameraman if there was no eye contact between me asking the questions and the person speaking into camera. I liked the directness of somebody speaking into camera. There were also obvious things like saving raw stock, because when you are doing interviews, you waste lots and lots of footage, but if you are the cameraperson you can switch off and then on again whenever things get interesting. There were moments when somebody else did camera I liked, and perhaps the cameraperson whom I could recruit happened to be in town at the right time. I would then do the sound recording and I would be happy that I was not doing camera because I was able to tap into more than my own immediate visual image. Sometimes I’m so concerned about the content of what’s being said and so involved in what’s happening that, being the cameraman, I have done the minimum to get the story told. Slowly I’m imposing a discipline on myself saying that OK, this was the exciting bit but I also need to get into where we are and what other things are happening -it’s like having two cameras, one camera which covers the main subject and one camera which picks up on incidental things.

John : Do you find yourself having to develop another eye then, so that there’s a kind of eye that you use to pick up on interviewees and there’s another eye that is concerned with landscapes ?

Anand : Not so much landscapes. I was brought up in the school of thought that believed that aesthetics for its own sake wasn’t worth it. The shot has to be integrally connected to what the film is saying.

John : Which school of thought is that?

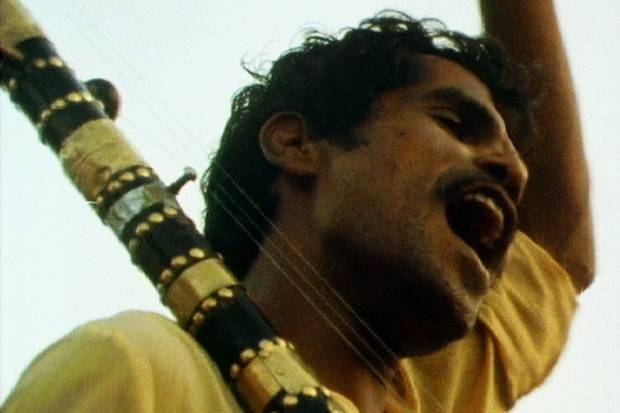

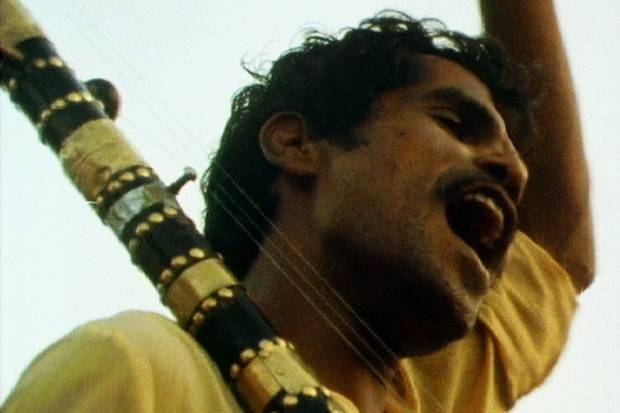

Anand : Well, I guess I trace it to Imperfect Cinema – the political logic of Fernando Solanas, Patricio Guzman and the other Latin -Americans, who were making films in the Sixties about Liberation Movements and felt that beauty for itself was not on.

I now find that my films work better when I provide breathing-space, moments which are connected but are not absolutely dictated by the story. There’s lot of intensity in different sections of the film and you need to have time to absorb what has happened before moving on to the next thing. In that sense I do find I use more of those moments now than I did before.

John : I never found that there was an absence of those moments of breathing – space. How do you achieve it ?

Anand : I guess one such example is where I stay on the characters after they finish speaking. The camera doesn’t switch off immediately, it lingers on. I find that a good way of staying focused and yet providing the space.

John : I agree absolutely with you and for me this is connected to the question of how dead time and songs work in your films. Literally each film at some point uses a popular song to illustrate an argument or provide you with moments when you can cut together a set of shots which would otherwise not cut together. So at the centre of all these films there is always this use of song.

Anand : Playful moments where you can get out of being immediately literal and are able to jump.

John : But there’s also a second register in the films which is relevant to our discussion on breathing-space – to do with the use of dead time. Your cuts are also sometimes quite elliptical but you don’t cut as fast as a number of mainstream film- makers.

Anand : No, I also don’t cut as fast because I find it disrespectful of the person I am talking to. Quite often I cut out very fast on the people I don’t like because then I just get the punch-line, the nasty bit that they’ve said and then I juxtapose it to something else. But, when it’s a sympathetic person that I’m talking to, I tend to stay on that person for longer because that person has other dimensions from the immediate dimension of what is being said and that has a visual dimension – it’s a way of saying that we don’t want to leave you right now but we have to do something else.

Ilona: But you often also shoot sympathetically the people with whom you don’t agree.

Anand : There’s a difference in my attitude to people I sympathise with but don’t necessarily agree with. A good example is the young Sikh militants in In Memory of Friends. They are at the same time victims and victimizers. They are victims of the State and also of a minority syndrome which has put them in an ideological trap. At the same time they are capable of killing people.

John : In each film there’s one or more people who a lot of care and attention is lavished on, not necessarily by being given more time but by bring framed differently, they’re returned to – for instance, in the new one [ Father, Son and Holy War ] there’s the woman…..

Anand : There are two women – there’s a working class Hindu woman who, against all odds, is against the Sati*. (*Sati – an outlawed practice which at times resurfaces in modern India, where a wife is burnt alive on her husband’s funeral pyre) All the other people around her are pro-Sati, and had been brought into this manipulation but she had not. And she taught herself through adult Literacy Courses and had come out of it and is very, very strong. In the second part of the film there’s the Moslem woman whose husband was killed and she was raped but she has incredible humanity. After all the things that have happened to her, she has no hatred and she says: “My Hindu sisters are helping me through this and so it’s not a question of Hindu/Moslem”.

John : That leads me to ask you something about the intentions of the films. When you set out to make them, do you have in the back of your mind an ideal figure who should figure in the frame?

Anand : No.

John : So how do you come across those people?

Anand : Accident.

John : Always accident?

Anand : Almost always accident – that’s the advantage of shooting for such a long time. Most of the films have been at least two or three years in the making and over that period you run across exceptional people, who do not necessarily speak very well but whose experiences are very important for the film. So that in terms of framing them, that’s quite unconscious. When I like somebody, or when I get into it, there’s probably technically something which I can’t define, which is not pre-planned. May be something happens and my respect for the person gets translated direct to the camera, or the cameraperson, in the framing, and everything takes a form.

In In The Name Of God, for example, there is a Hindu priest who we come back to again and again. He was murdered last year so my intuition about him being a very central figure in the whole drama that was unfolding was right. He was somebody whom they couldn’t allow to stay alive because he was a Hindu priest who was against the (Hindu) fundamentalists. He was right at the heart of Ayodhya, he was the Head Priest of that temple speaking out against them. For some incredible reason the media was not focusing on him and even after he has been murdered they hardly ever talk about it.

John : Over the last decade and a bit you’ve been dealing with a set of questions. What would you say those questions are ?

Anand : The main thing I have been obsessed with is the rise of fundamentalism; fundamentalist violence. If it was harmless, I would ignore it. But in India everyone can see the kind of hatred that’s resulted in increased levels of mindless violence against those whom the people who are killing don’t even know; anonymous murders for a cause, which make no sense, not even for the people who are doing it. The horror of that violence has kept me occupied for a decade.

John : How many films have come out?

Anand : Three. There was supposed to be one film. The material I was shooting became too complex so I had to separate it into three films which add up to a total of five and-a-half hours. So you can imagine how much more material there was.

John: How did you fund it overall ?

Anand : The only actual hard cash I’ve been able to raise was from Channel 4 – sales or pre-sales through Alan Fountain. I raise small amounts of money by selling films after they are made and I put it back into the next project.

John : Paradoxically, you work in political documentary filming but there is a clear connection between the way you work and the avant – garde – your films have a diaristic quality.

Anand: It would have been nice if I’d found the diaristic voice of : ‘Here I am. This is happening to me’. But I felt uncomfortable saying that I am important to this event. I was caught between not wanting to have an objective voice-of-God narration, saying: ‘ This is how the world is’, and not wanting to say : ‘This is how I see the world and this is all coming through me – through my interrelationship with the people that you see’. It’s obvious but I didn’t want to have to state it in the voice.

John : I meant diaristic in the sense that the Polish journalist Kapuczynski has defined it. When asked how he got this personal quality to his work, he said “Well, I do what is called in Latin, silva rerum – I live in the forest of things, and so what you get in my work is me bearing witness to these things.” Now, it’s clear watching your stuff that you’re also living it. The signature is your voice. We can always hear your voice in the background, prodding people, cajoling them, seducing them most of the time, to confess things they would otherwise not confess, pauses in the way you ask questions. You’re not simply stumbling across things. It’s clear that you’re also living through these things.

Anand : OK. Let’s put it this way. It’s diaristic but it’s not confessional. I haven’t got to the stage where I want to bare my soul on camera.

John : I think you are nevertheless revealing yourself. You largely shoot and edit your own material – you’re not the director in the traditional sense, ordering others to organize images for you. We can hear your voice, and we’re also watching your choice of images and frames for people.

Anand : I think what I’m doing is basically saying : ‘Here’s a liberal humanist who’s inviting other people’ – I believe other people are the same if only they would recognize it, and so – ‘come and see it this way’. What I choose to film are moments of terrible, irrational, inhuman behaviour which don’t make sense to anybody, once they happen to look at it in that perspective. So I’m just inviting people to look at it in that perspective. In real life all these terrible iniquities get mixed up with lots of grey areas. I choose moments that are very clear in themselves and then string them together. I’m always looking to find the moment of greatest, the most obvious contradiction which anyone can see, focus in on it for a while…

For instance, [in In the Name of God] there is the whole question – is it a temple or a mosque? There are people who believe that Ram was born in this spot and are willing to kill for it. But when I asked them when was Ram born, they had no answer to whether Ram was born millions of years ago or thousands of years ago. So that extreme logical perversity became revealed through one question… On the bridge to the mosque-temple in Ayodhya there are these guys who are so angry that they reveal they are quite happy that Mahatma Gandhi was murdered. They think it’s perfectly all right – that he deserved to die. Normally the fundamentalists would hide this deep nastiness. But if you catch them at the moment of passion and they reveal that, then the audience can see where it’s all coming from. There’s another example in In Memory of Friends, the film shot in the Punjab about Bhagat Singh, a Socialist, who wrote Why I Am An Atheist. We focus on the young boys, Sikh separatists, who had appropriated Bhagat Singh’s memory and were saying that after all he was a Sikh and he was martyred and we are like him. I say, ” What about the book – Why I Am An Atheist?” They say, “No, no no – that’s not written by him, that’s written by a Congressman”.

John : Last night I was thinking about your work and it struck me that in all your films you’ve been painting triptychs made up of three words – People, Power and Politics. But that over the years from Prisoners Of Conscience onwards there have been shifts and refinements clarifying questions in all three areas. For example, in Prisoners Of Conscience, there’s a very clear emphasis on who has power and where the battle lines are. By the time you get to In Memory of Friends or Father, Son and Holy War…

Anand : The situation itself has been changing. I have not changed that much. At the time of Prisoners Of Conscience there was the Emergency in India; martial law. The best minds in the country had been murdered or put in jail because they believed in social justice and revolution. So the film talked about political prisoners and State repression. But since then India became semi – democratic again and the situation has become more complex. The State was not the only enemy any more; there was fundamentalism. The State encouraged fundamentalism on the one hand and pretended that it was the secular force on the other.

John : The State has receded more and more in the work.

Anand : Because the State is no longer the big, bad… it’s too naïve now to say, if we get rid of the State we’ll be in great shape. Who is the ‘we’? Who are we talking about ? In 1977/78 when I made Prisoners Of Conscience, there was a naïve hope that the Left, the amorphous Left would come to power one day and create a just society. But the Left was divided even at that time and I was trying to create this unity on film.

John : Do you think you then switched from being interested in what served the Left to being broadly interested in what was in the national interest?

Anand : Even in Waves Of Revolution I already integrated the non- violent movement with the Left. The film is about the non-violent movement in Bihar, a student movement which was accused by sections of the Left of being too vague. They accused it of being pacifist and robbing people of more revolutionary methods. Then, in Prisoners Of Conscience, I covered Jayprakash Narayan (a Gandhian Socialist ) and non-violent methods of class struggle, as well as Maoist Revolutionaries who were talking about armed struggle. In this naïve and idealistic manner, I put them all into one boat as people who were fighting for justice, which I still believe they were. But there were obviously all kinds of contradictions which I wasn’t getting into. So in that sense there was always a mix between Marx and Gandhi, my ideal was always mixed.

John: You always oscillated between the two?

Anand: I didn’t oscillate between the two but saw the validity of both approaches. I never believed in armed struggle. I thought of armed struggle as being unfortunately necessary in some places like South Africa, but as it turns out, even in South Africa, non-violent methods worked much better.

John: But were you consciously going for a synthesis in the work or were these just influences that you felt you had to work with?

Anand: Pretty consciously, even in my forays into academia which were miniscule; I wrote a paper in 1971 trying to integrate Fanon and Gandhi. I went to America on a scholarship to Brandeis University in Boston. I took courses in the Black Studies department. The Black Panthers were active. The anti-war movement was at its height. We had to choose between whether we were on this side or that side. Then, I was obviously on this side. Lots of Indians were on that side because they didn’t identify with the Black Movement – as an Indian at that time you could choose whether you were White or Black.

John: But how can Fanon and Gandhi be integrated?

Anand: Basically Fanon made a fetish out of violence and Gandhi a fetish out of non-violence. They over-emphasized the means. Actually they were both being practical in their own terms. For Fanon violence was necessary to overcome the sense of inferiority that the black man had internalized. Only by striking back could he dispel this image of inferiority. For Gandhi, only through non-violence could you dispel this inferiority. In fact he temporarily called off the struggle in 1922 when in one incident a policeman was killed by the mob. I talk about this in the film In Memory of Friends as this is the moment when Bhagat Singh left the Gandhian movement.

The main point where Fanon is right is that he was warning against the danger that the independent struggle can easily mean Brown rule replacing White rule, because there is no attention being paid to class struggle. And where Gandhi is right is that human beings dehumanize themselves by the act of violence, that revolutionary violence degenerates into terror. So you have examples of both things: the Indian bourgeoisie taking over from the British. You have the example of many parts of Africa where violence continues, the most horrific forms. It’s only Mandela who integrated Fanon and Gandhi. It’s not the question of the means itself – but how do you participate in the liberation process without dehumanizing yourself or the other? For Fanon the act of violence is a liberating process. Maybe he was talking psychologically, that it wa not meant to be done by actual killing.

John : I must admit though, when I came to your house [in Bombay ] this year, suddenly you made complete sense.

Anand : You saw my posters. [Posters of George Jackson in Soledad Prison, the Nicaragua Solidarity Campaign, Cuban films…]

John : I saw the posters but I also saw photographs of your mother and Gandhi together, so that suddenly it didn’t feel like this weird, exotic mix, because it was something which related to your family background.

Anand : Well, family background was unconsciously part of it. I never thought it out. For instance, when I was growing up I was totally frivolous in college in Bombay, in terms of my uncles who had been in and out of jail for twenty years for opposing the British : one was a Gandhian and one was one of the founders of the Socialist Party. I loved them but I rejected active participation in anything. They themselves had rejected participation after independence because they saw the corruption that had begun in all the parties.

The Congress Party and even the Socialist Party were split up. One uncle was a Socialist who was disillusioned by Stalinism. They rejected politics as Politics with a big P, but they did social work. One started a rural university – an agricultural university. They worked mainly in the field of education.

Ilona: And your mother?

Anand : My mother’s a potter.

John : Well, this is the second bit which I thought was kind of interesting, because when I went to your house I suddenly realized that you came from this family in which art and politics were integrated in a very broad sense.

Anand : My mother went to Shantiniketan, which is Tagore’s arts university – started by Tagore before independence.

John : Which is in itself an attempt to synthesize art and politics – Tagore’s university is a product of that conjunction, isn’t it, the attempt to bring it together : Bengali nationalism and aesthetic internationalism. Suddenly within that broad, post – Tagorean Universe you made perfect sense.

Anand : Well yes, but it’s more complicated. My mother was from a traditionally business community, so being an artist was itself a rebellion of a kind. Luckily her father, my grandfather, though a businessman, was also a secret supporter of the independence movement, knew people like Nehru and Aruna Asaf Ali, and put some of his earnings into the freedom struggle. So he could not object when my mother decided to marry my father who was not well off but was from a socialist family that was fully immersed in the struggle against British Rule.

John : One of the reasons why I was keen to bring it up is that your work is distinctive in that it is not located by region or idiom. Clearly in the Patwardhan universe there’s always a wrestling with a national voice.

Anand : National and probably international, not only in the sense that I’ve spent so many years abroad now. Over the years I’ve spent at least five years outside the country but, before I went abroad, there was a search for a national voice, or a human voice, because that was something we were always brought up with – no boundaries.

John : Why documentary?

Anand : I fell into it by accident because when I was a student at Brandeis University in 1970 the anti – war movement was very strong. Brandies was the East Coast student centre of demonstrations against the Vietnam War. Berkeley was the West Coast one. So we were right in the middle of the anti – war movement. Angela Davis, Marcuse, Abbie Hoffman, Jerry Rubin – all came from Brandeis which was this tiny university of three thousand people.

I went there to do English Literature, to have a good time and go back to India and be a publisher or whatever. I wasn’t even that keen on being a publisher but at the age of twenty whatever you think that you want to do is complete guesswork, so this was a possibility. I liked literature until I started to take it up academically and then I got bored with it.

John : And how did that lead to documentary?

Anand: So I switched to Sociology at Brandeis. This was a big change from India, where you had to mug things up by heart and produce them in the exam. Then, in America you could pick different subjects of your choice. So I did a course on Theatre Arts and borrowed film equipment and did a small film : I shot a film of anti -Vietnam War demonstrations. Then I made a film on students at Brandeis trying to raise funds for Bangladesh refugees. In 1971 Bangladesh hadn’t been created, but there were very many people dying of starvation. So we tried to raise funds by organizing a fast, asking people not to eat for a day and send the money to the refugees. I interviewed people on that day on whether they were fasting or not. The film was called Business As Usual because most of the interviews were about people saying : I’ll give some donations but I’ve got to eat to do the Chemistry test or, I’ve got a basketball game, or whatever. I inter-cut that with shots of the refugees. It was crude but funny.

John : I’ve never seen it.

Anand : I’m embarrassed. I have long hair and speak with a slight American accent…. So anyway, since you ask : Why documentaries? It’s not just why documentaries but why film? After this first small film and after I finished university and got arrested for opposing the Vietnam War… my visa was gone; so then I worked with Cesar Chavez in California – the Farm Workers’ Union made up largely of people of Mexican origin. I then went back to India and worked in a village for a few years. There I didn’t do anything with film but I had a still-camera and we made a tape-slide show about tuberculosis, which was one of the problems there, to motivate people to keep coming to the clinic after taking the initial treatment. People used to take the initial treatment and then not do the follow-up and get sick again.

I didn’t do anything with film until 1974 when I’d gone to Bihar to join a student movement against corruption, or to observe the movement, and then got involved in it. They asked me to take pictures on a particular day when demonstrations were being planned; a big demonstration where there was going to be police repression, so they said : take pictures as proof. So I went back to Delhi and instead of a still camera, I thought I’d shoot it on film. I borrowed a Super 8 camera from a friend and took that friend back, and we went and shot that day’s demonstration. Eventually we thought we could do more than just having some dramatic footage on Super 8. We projected it on a screen and shot it with a 16mm camera. That became the basis for Waves of Revolution. Then the Emergency was declared in India and all the people who were in the movement that I was filming were put in jail. The movement was crushed. I could have been in jail as well but I got a teaching post in Canada to do my Master’s and smuggled out this film in pieces and reassembled it in Canada, and then started showing it against the Emergency in India. So again, no film-making between that time and much later when the Emergency was over and I made Prisoners Of Conscience. In twenty-three years I’ve made only seven films. Now I see it is the only useful thing that I can do.

John : Let me get this right. I’m sure you don’t mean that you had an Aaton [movie camera] and a Steenbeck [editing table], and made all that sort of space by default, I mean clearly…

Anand : By that time I was clear. This happened quite a long time ago – at least ten years ago I figured out that I was primarily a filmmaker because I saw how this was being used and also this was the most fun that I’d had. I was happy being able to feel useful as well as doing something that I enjoyed.

John : Which film were you working on when you realized that you were, for better of worse, a filmmaker?

Anand: I think it was between Prisoners Of Conscience and A Time To Rise, which was the film I made in Canada. The fact is that after A Time To Rise, economically things became better for me in that I didn’t have to borrow money all the time to make films. Until Prisoners Of Conscience and even till halfway through the making of A Time To Rise we were forever in debt, borrowing money from friends, living off goodwill. But once A Time To Rise was made and won an award, the Tyne Award in Newcastle, then Channel 4 bought telecasts of it and I slowly developed a relationship over the years so that I could get some money for the films, so that I didn’t have to run around raising money all the time – I guess that from there it became a kind of career. At least it became viable to make films, financially.

John : At the time that you were politically engaged and saw films as just one more tool to be used in an ongoing struggle, were you already interested in the theories of Imperfect Cinema?

Anand : I don’t want to over-emphasize that because I’ve never been very theoretical. It wasn’t reading Solanas and Getino’s or Espinosa’s articles. I don’t think I’ve even fully read “For an Imperfect Cinema”. It’s not particular articles or particular theories that I’m referring to. Actually, it was there in the air everywhere. It was not just coming in through film theory. It was there as a political ideology of helping the movement, so I guess my formative years were at a time when the weight was not on aesthetics or theory. It’s not that I am unaware of the aesthetic but the aesthetic is not something that I try to achieve. It’s there as a by-product of the process which is the only aesthetic I trust, even in other people’s work. It’s in Marlon Riggs’ Black is and Black ain’t which I have just seen.

John : [We met for the interview in November 1994, the day after the screening at Marx House of Father, Son, and Holy War organized by Women Against Fundamentalism and the Alliance Against Communalism and For Democracy in South Asia.] How did last night’s screening go?

Anand : It was full – we had people standing. The place is very small, so there was almost a hundred people there, in a seventy- people place, and the projector didn’t work so we wasted an hour and lost some people – we got it going again. After this new film is screened, I’ve noticed it takes a while for the conversation to get going – it’s really slow.

John : Do the same questions always come up?

Anand : One question that always comes up eventually is : Are you saying that women are better than men? – which is funny because it never got asked when my utopia was class struggle. Nobody said : Is it true that when workers of the world rule everything will be all right?

John : [On 10 May, 1995 Anand Patwardhan was passing through London after having shown the film in the US.] Did they ask the same questions?

Anand : Yes, but two other questions. One: Why no class-consciousness in the last film? Two: Why is the view of women essentialist?

Ilona : And what are your replies?

Anand : Class is running through it like a red light, but they didn’t notice. My reply to the second question is in the voice-over at the end of the film. Father, Son, and Holy War is not so much about the predicament of women as it is about the brutal socialization of men. In contrast to many of the men in the film, women may appear to have been romanticized, but a closer reading should reveal that this is hardly the point. A woman at the last screening was shocked that a man can make this film. She said that patriarchy victimizes females – males have no right to complain about patriarchy because they are privileged. Obviously patriarchy does not only victimize females.

Ilona : What kinds of films influence you? Do you love cinema?

Anand : I don’t think I love cinema in the abstract. I wouldn’t call myself a cinephile. Obviously there are some films that I love.

John : There was an interesting moment. I went to see Anand. We hadn’t seen each other for about two years. We were sitting down talking and it became clear about halfway through that the only way we were going to proceed in the conversation was through a film. So he said, “Well, I have a collection of Amos Gitai’s films and a collection of Ogawa- which one would you like to watch?”

Anand : I’d just got a tape by Amos Gitai which I hadn’t seen. I’d read about Amos’ work but I hadn’t had a chance to see anything until I got some tapes.

John : But the interesting thing was that we sat down, two friends who hadn’t seen each other for years, to watch Wadi, I think It was.

Anand : Ogawa’s film also was incredible. Shinsuke Ogawa died a year-and-a-half ago – a Japanese documentarist who made incredibly engaged films. He made one film in ten years, after living with the people for years. He made those films about the peasant and student takeover of the airport in Narita. They engaged the Japanese authorities for years and years, not giving up the expropriated land.

Ilona : But you didn’t as a child spend your time at the movies, or as a student, or at any time in your life? It wasn’t that sort of thing?

Anand : I have a funny story about that. As a child I hated cinema. I was scared. My parents took me to see Robison Crusoe and I was so scared because I thought that people really died on the screen. I was in tears. I refused to see any films after that for years because I was too scared. Finally, at ten or eleven they took me to a Walt Disney movie which had no human beings in it – The Living Desert. Then I got scared of the snake eating the rat.

John : Authentic Gandhi even then.

Anand : So then the film that I liked was Peter Pan and I went to see that many, many, times. I don’t know why I liked that. I haven’t seen it recently.

Ilona : So this is when you were a child. And your parents weren’t particularly film-goers either?

Anand : Yeah, they went. They were part of a Film Society. The Bengali connection with my mother meant she knew all sorts of filmmakers.

Ilona : What about Satyajit Ray? When did you first see him? Did you see Pather Panchali first?

Anand : I didn’t see Pather Panchali until I was twenty, or thereabouts. My Ray story concerns my film Prisoners Of Conscience. Ray was one of the few filmmakers, who refused to support the Emergency. Lots of other well-known filmmakers, whom I won’t name, went along with the Emergency because they were too scared to oppose it; some even made propaganda films for the government. But Ray refused to do that and Prisoners Of Conscience was about political prisoners during the Emergency. Even after the Emergency it didn’t get a Censor’s Certificate because it included sections about Maoists in prison. We were doing a campaign to get the film cleared by the Censor Board and Ray wrote a letter on my behalf to the Censor Board, after which it got passed.

John : Did you ever meet him?

Anand : Yes. He came to see the film and he wrote a letter. Once after that I saw him. He was a true liberal, in the best sense.

John : But you didn’t then see some connection between his values as a liberal and his value as a filmmaker, or did you?

Anand : I never chased up Satyajit Ray’s films but inevitably you have many chances to see them because they’re shown so much in many, many places. Over the years I’ve seen many of his films that I developed a liking for. I like Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne [ The Adventures of Goopy and Bagha ] a lot. It was very playful and it was a lovely children’s story: the good moral allegory. I liked Charulata and Days and Nights in the Forest, although in retrospect Days and Nights in the Forest has problems about having somebody made up as a tribal person. Maybe they could have developed a rapport with indigenous people so that they could have played themselves.

John : Is that one of the major advantages for you in making documentaries?

Anand: Yeah – there are so many reasons for doing documentaries rather than fiction, but one reason is that I am not confident enough to create. I wouldn’t feel that I trusted myself enough to make up the whole story and the character, and so many other things that you do in fiction. I feel much happier with found material; with things that are there. My job is to record those things. Obviously there’s some creativity involved or some manipulation in the way that it comes out on the screen but I’m not starting from scratch in terms of what is in front of the camera. In fiction, the responsibility of creating every element in the whole thing is mind-boggling.

John : This is connected to my earlier question on the confessional element in documentary. One of the ways in which you are obviously present is through the editing. Do you have any particular ideas about how you approach editing, or is it – this shot works, next I cut to another shot?

Anand : I think the style or the structure of the films is determined by the material rather than by pre-planning. My last film, because it was made over such a long time doesn’t have a clearly linear story-line, while the other two of the three films that I’ve done on religion were more linear. Although In Memory Of Friends is also not linear in the sense that it uses Bhagat Singh’s writing and it moves in between the past and the present. In The Name Of God has a linear logic that goes from point A to point B by following the chariot journey, leading up to the attack on the mosque. In between, different things are woven which eventually help the audience to understand the growth of Hindu fundamentalism. I knew when I was shooting that this was important and that was important, but I didn’t know exactly how they were connected to each other. So, in all the films, I’ve been editing sequences which held together. For instance, when I did the interview with the woman from Rajasthan, whom we talked about earlier, I edited her, kept the things that I thought were important, left it as a chunk and then moved on. As I’d shot over the years I edited different sequences, boiling it down to what was important, but not necessarily at that point connecting them all up. Other things I just left separately. Over many years a whole mosaic developed. Then basically, six years after I had started shooting, it all fell together, the pattern began to emerge.

John : Did you just wake up one day and it all kind of made sense?

Anand: No. By which I mean that if I had finished the film two years ago it would have been a totally different structure. For instance, 1993 was the year when the Bombay riots occurred, so obviously the Bombay riots are a very important part of the film. But I’d already been shooting for six years before that and I may have finished it earlier but I never felt, I wasn’t clear what to do with everything, how it all linked together. But when the Bombay riots occurred it…

John : Crystallised things.

Anand : Yeah, crystallized things. It also became the most explicit example of what the other material was talking about anyway.

John : I hate it when people ask me this question, but I thought I’d ask it anyway because you might have a slightly more sophisticated way of answering it than I have. It’s to do with motifs in film. All of your films have these motifs – sometimes they’re visual, some-times they’re political. You mentioned that the second film culminates at Ayodhya – the journey to Ayodhya punctuated…

Anand : The journey to Ayodhya is the backbone…. In the Punjab film the writings of Bhagat Singh are the backbone so everything was hung around that.

John : In this one, this new one?

Anand : In this one, the Bombay riots are the motif that comes to mind, the fire of the riots and the fire of sati. They all get linked. That’s why the first part is called “Trial By Fire” because “Trial By Fire” is the fire which the Hindu god Ram subjected Sita to. Sita was his wife and Ram made her undergo an ordeal by fire to prove her chastity. She had been abducted by the enemy king and after being rescued she was forced to prove that she had not been violated by sitting on fire. In the Hindu religion, fire is a symbol of purification. And the concept of ‘purity’also brings up the question of religious, caste or race “purity”. Or, in other words, the definition of difference or ‘otherness’ which is at the heart of fundamentalist violence.

Ilona : Can you give an example of editing and how it ties up to question of motifs?

Anand : Take the child with the wheel who wanders off into the foreground [in In Memory of Friends]. There are possible meanings to that but they are free-flowing. At the literal level the child has its own meaning – a child is innocent – a little Sikh boy in the village playing just before a sequence when women are cooking and they are saying, “there is no difference between Hindus and Sikhs” – ordinary rural life which is integrated. In the same sequence it cuts to a top shot of many bullocks eating out of one trough and pans over to the countryside; in a sense it illustrates but it doesn’t have to be seen in that way.

Ilona : Who distributes you? Who sees the films?

Anand : In India the main method of distribution is TV but, because of the nature of the films, there has been a big battle to have them shown. Only one film, Bombay Our City, has been shown on TV, after a four year court case which reached the Supreme Court. The film had won the National Award for Best Documentary of 1986 and there is a general principle that award winning films are to be shown on national TV. We argued that not showing the film on TV was a denial of Freedom of Speech and of the public’s Right to Information, both guaranteed in the Indian Constitution. TV at that time was Government controlled and there was one channel. They could not find constitutional grounds to counter this argument. At present the Bhagat Singh film as well as In the Name of God are in the Bombay High Court because despite winning national and international awards they are not being shown on national TV. The latest film Father, Son and Holy War won 4 international and 2 national awards, and will inevitably follow (legal) suit. These court cases take years to get resolved but at least they help to keep the films in the news.

The films are in Hindi [and in the languages of the participants ]. In the absence of TV – film societies, trade unions, women’s movements, civil liberties movements show the films. In the old days, the 1970s, we used to show them on 16mm projectors but now the screenings take place in video. So my main method of reaching people in India is distributing video cassettes. They are bought mainly by activist groups; each cassette is shown hundreds of times. Because they are tied to movements for communal harmony they have a campaign value: people who are campaigning against fundamentalism have very little to use as material. Same in Britain, America, Canada as there are so many Indians there. They are shown in festivals, universities, departments of sociology, political science, anthropology – in South Asia, America and Canada.

John : You’re now clearly an international documentarist of some repute. You get invited to festivals. You sit on panels….

Anand : But it’s still a struggle getting my films shown. I still feel at most festivals totally marginalized. I feel that even, for instance, here in London, the screening [at the London Film Festival, November 1994 ] was marginal in that it has no effect on the real consciousness in England or anywhere else – it hasn’t any impact on a larger reality. It’s OK to develop a coterie of friends and people who like your work; there are always enough to fill one or two auditoriums but you can’t justify that what you’re doing is politically useful if it stays at that level. The question is how many people are seeing it and thinking about the issues raised in it. They are still totally ignored by the mainstream media. It would be written about maybe in a few alternative papers [ a few months later Anand shows us an enthusiastic review in Variety. ed.]. I don’t know what it is actually. I don’t know why films like this have to be in the margin. Because it’s not as if they are boring.

John: Do you find that there’s been a kind of shift in the relationship in an international sense between documentary and features? Clearly films at festivals still make an impact. They are a very particular kind of film, so is it simply that a particular kind of film now achieves greater prominence, sometimes at the expense of another. Or had this always been the relationship…

Anand : Between fiction and documentary?

John : I mean, has documentary lost the ground in how it’s programmed, perceived, disseminated…?

Anand : There’s definitely a shift from the 60s and 70s – I wouldn’t even distinguish between documentary and fiction – but between say, for want of a better word, politically progressive films and the mainstream commercial films. Not necessarily commercial but whose raison d’etre is either straightforward entertainment or playing up to people’s expectations. Even what is considered alternative is defined by the same people who define the commercial.

Ilona : [March 1996] When will we see Father, Son and Holy War on Channel 4 ?

Anand : In the past, Channel 4 showed all my films, but I’m afraid the respect for independent and alternative voices has eroded. They asked for the film to be “reversioned”. I even agreed to do the cut-down myself – it would have meant sacrificing fifteen minutes from the original two hours. But they did not invite me to the editing table. They wanted to do it themselves. I had to refuse. I am deeply disappointed, as everyday something happens to illustrate the continuing relevance of the film to the times we live in – whether it is the rise of Hindu fascists to power in the State of Maharashtra where I live, or the sight of men in India and Pakistan demanding blood each time their cricket team loses a match.

[In mid-July, the Bombay High Court ruled in favour of Patwardhan’s petition to compel Doordarshan TV to screen ‘In Memory of Friends’ in prime time on one of its two main channels. Doordarshan’s inconsistent contentions that the film offended religious sensibilities, promoted atheism and class consciousness while simultaneously affording a platform to Sikh nationalism were rejected in toto by Justice A.P.Shah. His judgement vindicated both the integrity and public interest of this documentary. It is difficult to envisage comparable recourse to constitutional law guaranteeing public freedom of information in Britain. Channel 4 did screen Part 1 of ‘Father, Son and Holy War’ in the small hours of 6/6/96, but there are no plans to show Part 2.ed.]

Ilona : What is your most recent film?

Anand : ‘A Narmada Diary’. Narmada is the name of a river. It was shot on Hi-8 video and documents the struggle against the dam over five years. It was produced and directed with another filmmaker, Simantini Dhuru, who also shared the camera work and editing. Her sister is an activist in the movement. The film began as an informal archiving of various events. Over the years we became very close to the movement and the film reflects this intimacy.