By Serge Daney

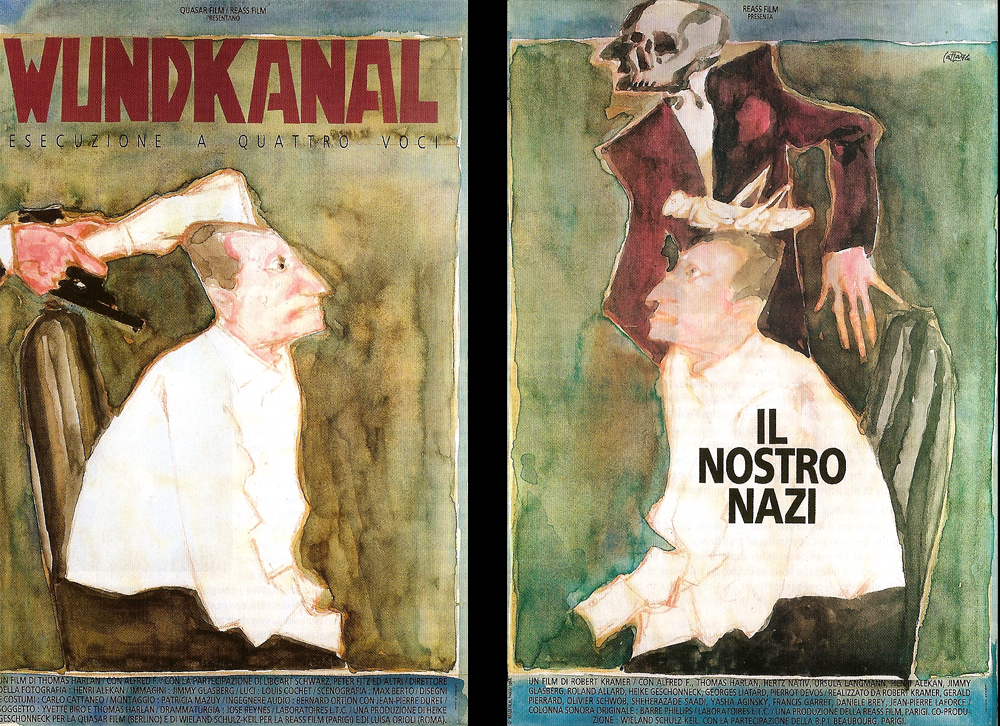

Originally published as ‘L’ ethnographie militante de Thomas Harlan’, Cahiers du Cinéma n° 301 (June 1979)

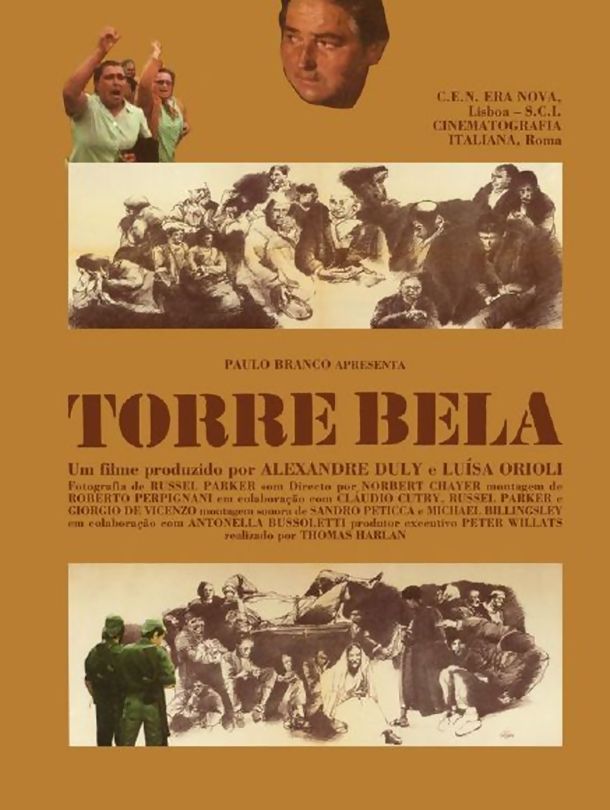

Torre Bela is first of all an extraordinary document, of a type that emerges occasionally from the heart of a struggle or from boundary situations, when the determination to “keep on filming” surpasses the ideas – whether common or not, committed or not – of the person who films. Enthusiasts of the “real” and cannibals of the “direct action” (among which we count ourselves) will be flabbergasted by the film of Thomas Harlan. Rarely have we so clearly seen the making and unmaking of a a singular collectivity, itself composed of singularities, caught in a political process through which it is the blind truth, the point of utopia.

But there is more. Torre Bela shows – materialized, embodied – all the key ideas of political and theoretical leftism from the past decade. “As if we were there” – but precisely, we are no longer there: no one is. We see the flesh which ostensibly nourished yesterday’s discourses, the images in which the sound was “turned up too loud” (1): voices speaking up (chaotic: one day the film will be used for the study of farmers’ jargon and the Portugese language), popular language (and its stammering), people in arms (the strange soldiers of the MFA (2)), popular memory (with its tales of bitterness), the fabrication of a mass leader (Wilson) and the distrust of heroes (Wilson again), contradictions among the people (men/women … ), cynical and silly discourse of the enemies of class (amazing interview with the Duke of Lafões), etc..

Of course, all of this arrives late. In all of this we have believed, but it has come undone, and suddenly, this film appears, in hyper-realistic precision, both as a sonogram of the heart of what has been and as the hallucinatory spectacle of what we believed in (the people, autonomy, revolt). Surely, one doesn’t have to blindly believe in it to begin to see it, just as one didn’t have to see it at all to continue to believe in it. This “gap” between what is believed in and what has come undone – “le cru et le cuit” (3) – is perhaps the truth of the few “good militant films.” One had to wait until the mottos and slogans stopped reassuring before the images finally arrived… though to a devastated landscape. The experience of the popular commune of Torre Bela (1975-1979) ended the year when the movie was finally finished and “released.” We – neither us nor Harlan or anyone else – no longer have a relationship to these images except one of ethnographic cannibalism (and isn’t ethnography our cannibalism of us?) or of perverse aestheticism (Torre Bela as utopia, another utopia).

That is how it goes with cinema. Cinema is never on time. Let alone the cinema of intervention: the only one that, in order to exist, must take time establishing its material; the one that is never finished fast enough. The filmmaker finds himself in an impossible, even seamy situation in which he can dwell, in spite of the conventional piousness of his discourse. Whether it is Moullet paying himself the luxury to finally pull off a militant-didactic-and-third-worldist film at a moment when nobody knows what to do with it (whereas before, everyone wanted to but nobody knew how) (4); or the strange temporality of the Ogawa experience, redoubling the atrocity of the real with a neverending and equally atrocious film (5), or Godard spending five years editing a film on Palestine (6). It’s the same point of arrival, the same Pyrrhic victory, the same Parthian arrow, the same revenge of the artists on the political chiefs and the militants: here is the flesh of the ideas you thought you had, here is the referent to the words you have misused, the proof that what you talked about (without having seen it) has indeed existed: it is shown to you only because it’s over. This perverse dialectic of what is believed in and what has come undone is today the last word of so-called “documentary” cinema (from Flaherty to Ogawa, from Rouch to Harlan, from Ivens to Van der Keuken): a look all the more acute – even abrasive – for it establishes the trace of that which has no future.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Translated by Stoffel Debuysere and Charles Fairbanks (Please contact me if you can improve the translation).

Torre Bela will be shown at the Courtisane Festival 2012, together with José Filipe Costa’ Linha Vermelha

In the context of the research project “Figures of Dissent (Cinema of Politics, Politics of Cinema)”

KASK / School of Arts

translator’s notes

(1) Here Daney is probably making a reference to Jean-Luc Godard’s Ici et ailleurs (1976), in which the filmmaker denounces images – used not in the least in his own militant work from the Dziga Vertov Group period – in which “the sound is turned up too loud” and the soundtrack “insists on one voice dominating another.” In the film he states: “Why have we been incapable of seeing and listening to those quite simple images and have said, like everybody, something else about them? Something else than what they said, however. Probably we don’t know how to see, or to listen. Or the sound is too loud and covers up the reality… To learn to see in order to hear elsewhere. To learn to hear oneself speaking in order to see what the others are doing. The others, the elsewhere of our here.”

(2) Movimento das Forças Armadas

(3) On several occasions Daney has played with the multiple meanings of the words “cru” and “cuit” in reference to cinema. “Le Cru et le Cuit” is also a book by Claude Lévi-Strauss, but its English translation, “The raw and the cooked”, is incomplete. “Cru” is also the past-participle conjugation of the verb “croire” (believed / to believe). “Cuit” does not only mean “cooked”: it also denotes “done”, not necessarily referring to food.

(4) Luc Moullet, Genèse d’un repas (1978)

(5) Shinsuke Ogawa, Sanrizuka Series (consisting of 7 films, made between 1967 and 1974)

(6) Jean-Luc Godard, Ici et Ailleurs (1976)