By Jean-Luc Godard

Originally published in Cahiers du Cinéma n° 300 (May 1979), which was completely put together by JLG.

Elie Sanbar,

somewhere in

Palestine

19th July 1977.

We are really sad that we were unable to see you, but the shooting with Camille took more time than expected. Talking with children was much harder than with Ludovic. (1)

I would have liked to have your opinion about a text and a picture that I’m considering to put in the third programme, which is about bringing things to light. (2)

We are wondering how, at a given moment, the Germans have become such great executioners and the Jews such great victims.

The Jewish people are a very original people, and their history is a very interesting one. It still remains to be told.

Itâ”s a history of you and me, that is: of oneself and the other.

At a certain point in time, the Germans and one German in particular, supported by the other Germans, wanted to become other without forsaking anything of themselves, that is: to simply expand until infinity, multiply themselves until death, a bit like cancer, or like those who give lessons, those who produce texts.

And amongst the other people hindering them in their desire to spread their truth everywhere, which of course meant all the other people in general, except for the Japanese who were doing similar things at the same time, but it was above all the people who stood out as other from the outset, for whom being themselves first of all meant being an other, who started out from difference rather than alikeness, and who considered themselves like that and not otherwise, since the night of time: the Jewish people.

Therefore the Germans not only had to exterminate them but wipe them from the face of the earth, and in a spectacular fashion at that.

And that’s how the original image of the Jewish people finally found a legitimate place.

But Israel never acknowledges it: that they needed a second and terrible image, that of the German madness, in order to gain this right to have a place of their own, to be fully legitimized, and that it’s a burdensome inheritance.

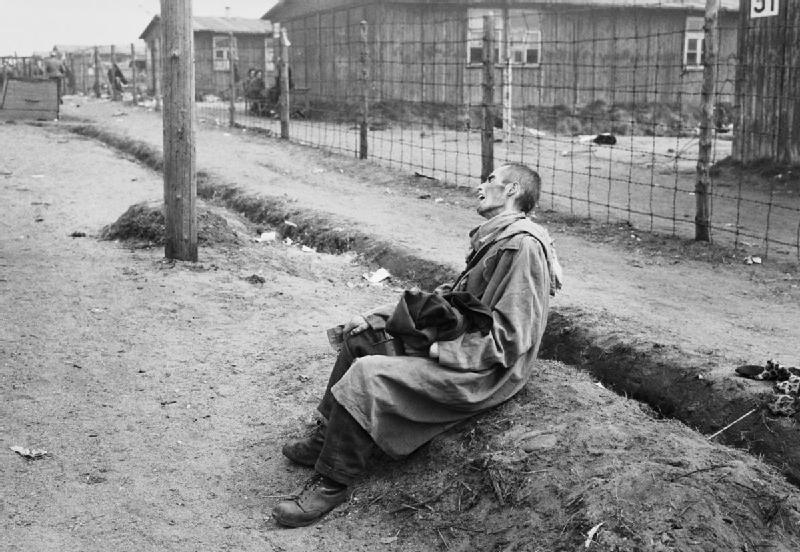

Yet this is visible in any image of the German camps, but not if we look thoughtlessly because it’s too horrible to look at, too horrible especially to exist only because of the hate for the other.

Nobody knows where things will end up in the Middle-East, but we can somewhat know where and when it has really started.

It was here, in Europe (it is thus also our war, and if it wasn’t ours we would not understand why the people here get so exited about Libanon rather than South-Africa or Cambodia).

In Europe and with one of these images, not just any at that, and with it’s true legend.

The current war in the Middle-East is born in a concentration camp on the day when a great Jewish outcast, on the verge of dying, was called “musulman” by some SS. (3)

One really had to be the essence of evil to be able to inoculate the memory of six millions of Jewish dead with the memory of the hate for the other, but for the other Jew this time, because in thirty years time the Jewish people would meet its alike, an other Jewish people, and on a very specific territory, not in the night and fog, but in a place somewhat in the sun, and who told them: I am the same as you, I am a Palestinian.

We have often spoken about this: that an image is useless if it is not accompanied by its alike in a different situation.

But perhaps that’s why images are frightening. Even alone, if well taken, it calls for an other, and first of all it’s rightful legend, like justice establishing balance.

Under this picture of a Palestinian woman who is grabbed by the hair by one of Begin’s soldiers, the English text says: “West bank say no”. (4)

In a magazine for professional photographers, its legend would be: Nikon case, 58mm lens, I/60 to f: 4, Ektachrome X.

It’s not that they are false, these legends, but rather incomplete, and deliberately so. That’s where it doesn’t move, in the most simple sense: it prevents to move, further, not as far, no matter, it’s about putting a stop to circulation.

Perhaps a cinema magazine made with other people, people who would need to establish relations with other people, living under different skies, perhaps this would salvage a bit of the circulation in our impotent capability to imagine.

—————————————————————————

Translated by Stoffel Debuysere (Please contact me if you can improve the translations).

In the context of the research project “Figures of Dissent (Cinema of Politics, Politics of Cinema)”

KASK / School of Arts

translatorâs notes

(1) References to Camille Virolleaud in France/tour/détour/deux/enfants and Ludovic in Six Fois Deux, Part 6B: Jacqueline et Ludovic, both made with Anne-Marie Miéville.

(2) Reference to France / tour / détour / deux / enfants, Deuxième mouvement (Lumière/Physique).

(3) In regards to the use of the word “Musulman”, Andy Rector sent me these lines taken from This Way For the Gas, Ladies and Gentleman (1959) by Auschwitz survivor Tadeusz Borowski:

page 32:

“Just as we finish our snack, there is a sudden commotion at the door. the Muslims* scurry in fright to the safety of their bunks, a messenger runs into the Block Elder’s shack. The Elder, his face solemn, steps out at once.

‘Canada! Antrten! But fast! There’s a transport coming!'”

(…)

*’Muslim’ was the camp name for a prisoner who had been destroyed physically and spiritually, and who had neither the strength nor the will to go on living — a man ripe for the gas chamber.

Borowski, quoted in the introduction, page 22:

“The first duty of Auschwitzers is to make clear just what a camp is…But let them not forget that the reader will unfailingly ask: But how did it happen that you survived?…Tell, then, how you bought places in the hospital, easy posts, how you shoved the ‘Moslems’ into the oven, how you bought women, men, what you did in the barracks, unloading the transports, at the gypsy camp; tell about the daily life of the camp, about the hierarchy of fear, about the lonliness of every man. But write that you, you were the ones who did this. That a portion of the sad fame of Auschwitz belongs to you as well.”

(4) Menachem Begin was the founder of Likud and the sixth Prime Minister of the State of Israel.