Figures of Dissent : Jean Genet

24 November 2011 20:30, KASKcinema, Gent. A Courtisane programme.

“Power may be at the end of a gun, but sometimes it’s also at the end of the shadow or the image of a gun.”

— Jean Genet

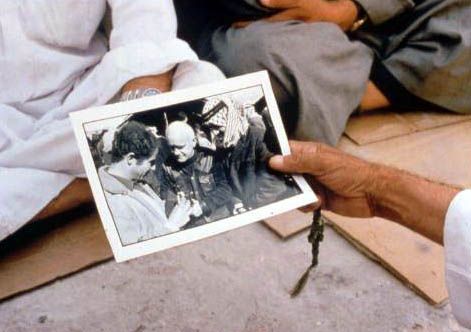

Orphan, prisoner, deserter, vagabond, writer, dramaturge, one-time filmmaker and overall poet : the life and work of Jean Genet (1910-1986) resists easy classifications. But if there is a constant characteristic in his unorthodox trajectory, it is an ever-moving feeling of resistance and rebellion. “Obviously I am drawn to peoples in revolt”, he says in an interview in the early 1980’s, “because I myself have the need to call the whole of society into question.” From his first novel, that would earn him the respect and recognition of the likes of Cocteau, Sartre, de Beauvoir and Breton, he manifests a profound aversion towards all forms of social consensus, as well as a deeply felt affection for those who do not “belong”. And yet, it wasn’t until Les Paravents, the closing chapter of a series of theatre plays that he wrote between 1950 and 1960, that Genet would – be it implicitly – take sides with a political resistance movement: the Algerian independence fighters. A few years later he would write a tribute to Daniel Cohn-Bendit, one of the protagonists of May 1968, and protest against the inhumane living conditions of immigrants in France. In 1970 he travelled clandestinely to the United States where he supported the cause of the Black Panther Party. That same year he visited for the first time Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon and Jordan, where he would remain intermittently until 1972. When he returned ten years later, he was confronted with the terrible consequences of Israel’s invasion of Lebanon. Genet would be one of first Westerners to witness the aftermath of the blood bath perpetrated at the Shatila camp by the Lebanese Phalangist Militia, with the tacit approval of the Israeli government. His Palestinian experiences are recounted in the essay Quatre heures à Chatila (“Four Hours in Shatila”) and in his posthumous novel Un Captif Amoureux (“Prisoner of Love”). He writes: “All these words to say, this is my Palestinian revolution, told in my chosen order. As well as mine, there is the other, probably many others. Trying to think the revolution is like waking up and trying to see the logic in a dream.” During the past two decades since he passed away, his writings have only gained more force. Two documentaries gauge the resonance of his work in the light of the continuous ghettoisation of Palestine.

Richard Dindo

Genet à Chatila (Genet in Chatila)

CH/Palestine, 1999, 16mm on video, colour, stereo, English spoken version, 99’

“Le titre du film de Richard Dindo est trompeur. Optant pour un intitulé de documentaire, Dindo, qui n’a fait que paraphraser l’un des titres de Genet, Quatre heures à Chatila, ferre en quelque sorte son spectateur avant de l’emporter dans un long poème sur le temps, de lui faire découvrir en companie du personnage attachant d’une jeune journaliste algérienne, jeune Arabe parlant difficilement l’arabe et comme habitée d’une peine infinie, que la meilleur façon d’aller dans la durée consiste à avancer dans les lieux. (…) (…) Armé d’une langue magnifique, Genet joue fondamentalement, tout comme il aurait misé au jeu, la fusion des strates temporelles. “Le présent est toujours dur, l’avenir est supposé l’être davantage. Le passé, ou plutôt l’absent, sont adorables et nous vivons au présent.” Pour se dégager de l’emprise de ces durées, plantées en chacun et apparamment inextricables, Genet va donc faire fusionner les strates du temps, ses strates du temps: son récit sera tout à la fois celui d’un premier séjour en 1970, d’un second en 1982, d’un troisième en 1983-84, et celui d’aucun d’entre eux. Et Richard dindo, qui a pour bonne habitude de coller littéralement aux textes de ses auteurs, vient à son tour mêler – et dissoudre – sa strate, celle du temps cinématographique, à celles de Genet. Il demeure ainsi dans l’oeuvre et effectue, en sa compagnie, sa propre sortie de la durée. Là où résidait la grande prouesse de Genet dans son Captif Amoureux, se retrouve le pari, réussi, de Dindo.” (Elias Sanbar)

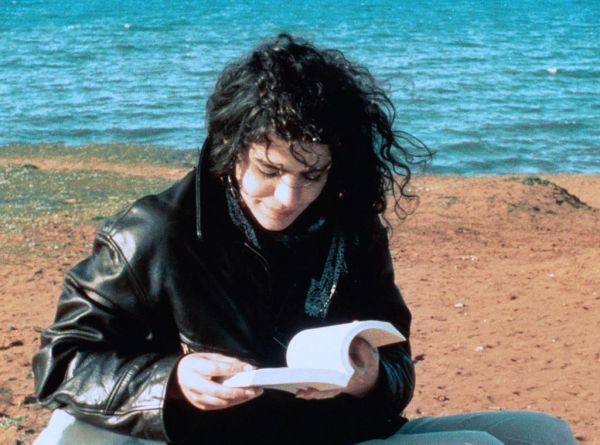

The Otolith Group

Nervus Rerum

GB/Palestine, 2008, video, colour, stereo, English spoken, 32’

“It is perhaps with Nervus Rerum (the title is taken from Cicero and translates as ‘the nerve of things’), the 2008 film shot in the Palestinian Jenin refugee camp on the West Bank, that The Otolith Group’s (Kodwo Eshun & Anjalika Sagar) vision achieves its greatest success. The film begins with the camera moving slowly up a backstreet in Gaza. Children look on silently as an eerie soundtrack deepens their gaze. Abandoned cookers line the sides of the road; graffiti is everywhere, a palimpsest of politics. Two men stand talking next to a pick-up truck filled with empty plastic bottles. ‘We are death,’ declares Sagar. ‘We are dead when we think we are living.’ The words are taken from Fernando Pessoa’s ‘The Book of Disquiet’ and Jean Genet’s book about Palestine, ‘Prisoner of Love’; they both distance us and draw us closer to the slow, quiet images of the settlement. (…) This is the success of Nervus Rerum and The Otolith Group as a whole: when image and voice fail to coincide; when the ‘big story’ of Palestine becomes a whole series of smaller tales; when representation fails because it has to.” (Nina Power)

In the context of the research project “Figures of Dissent (Cinema of Politics, Politics of Cinema)”

KASK / School of Arts