By Jacques Rancière

Originally published in the booklet accompanying the Pedro Costa retrospective at Tate Modern (25 September – 4 October 2009). The French text was published under the title ‘Politique de Pedro Costa’ in ‘Les écarts du cinéma’ (La Fabrique editions, 2011). Translated by Emiliano Battista.

How are we to think the politics of Pedro Costa’s films? The answer appears simple at first. His films are about a situation seemingly at the heart of the political issues of today: the fate of the exploited, of people who have come from afar, from former colonies in Africa, to work on Portuguese construction sites; people who have lost their families, their health, sometimes even their lives, on those sites, and who yesterday were dumped in suburban slums and subsequently moved to new homes—better lit, more modern, not necessarily more livable. A number of other sensitive themes are joined to this fundamental situation. In Casa de Lava, for example, there is the repression of the Salazar government, which sends its opponents off to camps situated on the very spot from where African immigrants leave in search of work in the city. And, starting with Ossos, there is the life of young people from Lisbon who, due to drugs and deteriorating social conditions, have found themselves in the same slums and under the same living conditions.

Still, neither a social situation nor a visible display of sympathy for the exploited and the neglected are enough to make art political. We usually expect there to be a mode of representation which renders the situation of exploitation intelligible as the effect of specific causes and, further, which shows that situation to be the source of the forms of consciousness and affects that modify it. We want the formal operations to be organized around the goal of shedding light on the causes and the chain of effects. Here, though, is where things become difficult. Pedro Costa’s camera never once takes the usual path from the places of misery to the places where those in power produce or manage it. We don’t see in his films the economic power which exploits and relegates, or the power of administrations and the police, which represses or displaces populations. We never hear any of his characters speaking about the political stakes of the situation, or of rebelling against it. Filmmakers before Pedro Costa, like Francesco Rosi, show the machinery that regulates and displaces the poor. Others, like Jean-Marie Straub, take the opposite approach. They distance their cameras from ‘the misery of the world’ in order to show, in an open-air amphitheatre designed to evoke ancient grandeur and modern struggles for liberation, the men and women of the people who confront history and proudly proclaim the project of a just world. We don’t see any of this in Pedro Costa. He does not inscribe the slums into the landscape of capitalism in mutation, nor does he design his sets to make them commensurate with collective grandeur.

Some might say that this is not a deliberate choice, but simply the reality of a social mutation: the immigrants from Cape Verde, the poor whites, and the marginalized youth of his films bear no resemblance at all to the proletariat, exploited and militant, which was Rosi’s horizon yesterday, and remains Straub’s today. Their mode of life is not that of the exploited, but that of a marginalized group left to fend for itself. The police is absent from their universe, as are people fighting in the name of social justice. The only people from the city center who ever come to visit them are nurses, who lose themselves in these outskirts more from an intimate crack than from the need to bring relief to suffering populations. The inhabitants of Fontainhas live their lot in the way that was so stigmatized during the time of Brecht: as their destiny. If they discuss it at all, it is to wonder whether heaven, their own choice, or their weakness is responsible for their lot.

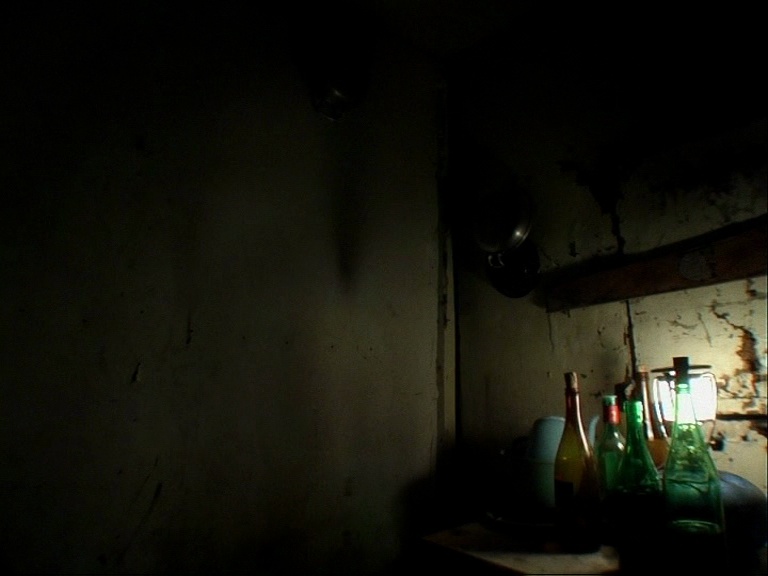

What are we to think of the way Pedro Costa places his camera in these spaces? It’s common to warn people who have chosen to talk about misery to remember that misery is not an object for art. Pedro Costa, however, seems to do the very opposite. He never misses an opportunity to transform the living spaces of these miserable people into objects of art. A plastic water bottle, a knife, a glass, a few objects left on a deal table in a squatted apartment: there you have, under a light that strokes the set, the occasion for a beautiful still life. As night descends on this space without electricity, two small candles placed on the same table lend to the miserable conversations or to the needle sessions the allure of a chiaroscuro from the Dutch Golden Age. The motion of excavators is a chance to show, along with the crumbling buildings, sculptural bases made of concrete and large walls with contrasting colors—blue, pink, yellow, or green. The room where Vanda coughs so hard as to tear apart her chest delights us with its aquarium green walls, against which we see the flight of mosquitoes and gnats.

The accusation of aestheticism can be met by saying that Pedro Costa has filmed the places just as they are. The homes of the poor are on the whole gaudier than the homes of the rich, their raw colors more pleasant to the eye of the art lover than the standardised aestheticism of petit bourgeois home decorations. In Rilke’s day already, exiled poets saw gutted buildings simultaneously as fantastic sets and as the stratigraphy of a way of living. But the fact that Pedro Costa has filmed these places ‘as they are’ means something else, something that touches on the politics of art. After Ossos, he stopped designing sets to tell stories. That is to say, he gave up exploiting misery as an object of fiction. He placed himself in these spaces to observe their inhabitants living their lives, to hear what they say, capture their secret. The virtuosity with which the camera plays with colors and lights, and the machine which gives the actions and words of the inhabitants the time to be acted out, are one and the same. But if this answer absolves the director of the sin of aestheticism, it immediately raises another suspicion, another accusation: what politics is this, which makes it its task to record, for months and months, the gestures and words which reflect the misery of that world?

This is an accusation which confines the conversations in Vanda’s room and Ventura’s drifting to a simple dilemma: either an indiscreet aestheticism indifferent to the situation of the individuals involved, or a populism that gets trapped by that same situation. This, though, is to inscribe the work of the director in a very petty topography of high and low, near and far, inside and outside. It is to situate his way of working in an all too simple play of oppositions between the wealth of colors and the misery of the individuals, between activity and passivity, between what is given and what is seized. Pedro Costa’s method explodes precisely this system of oppositions and this topography. It favors instead a more complex poetics of exchanges, correspondences, and displacements. To see it at work, it might be good to pause a second over an episode from Colossal Youth that can, in a few ‘tableaux,’ sum up the aesthetics of Pedro Costa, and the politics of that aesthetics.

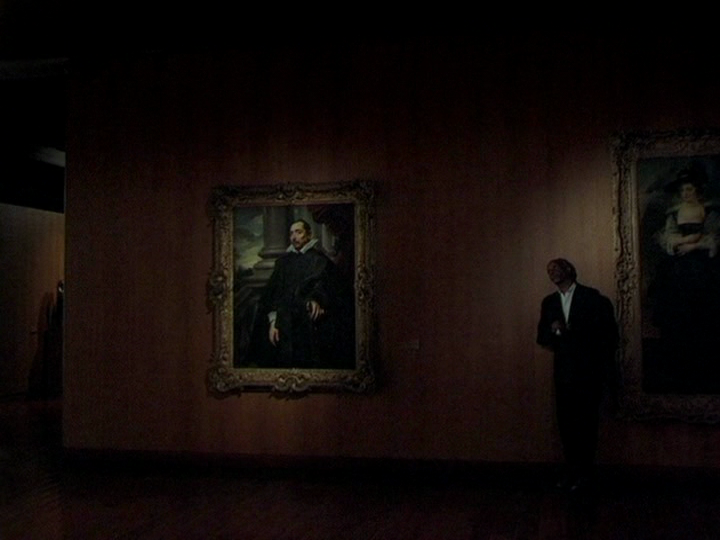

The episode places us, first, in the ‘normal’ setting of Ventura’s existence: that of an immigrant worker who shares a run-down place with a fellow Cape Verdean. As it starts, we hear Ventura’s voice reciting a love letter while the camera-eye frames a grey corner of the wall which is pierced by the white rectangle of a window; the four glass bottles on the window sill compose another still life. Urged by the voice of his friend Lento, Ventura’s reading slowly fades out. The next shot introduces a quite brutal change of setting: the still life that served as the set for Ventura’s reading is succeeded by yet another colored rectangle taken from a still darker section of wall: a painting whose frame seems to pierce with its own light the surrounding darkness which threatens to encroach on its edges. Colors quite similar to the colors of the bottles outline arabesques in which we can recognize the Sacred Family fleeing to Egypt with a sizeable cohort of angels. The sound of footsteps announce the character who appears in the next shot: Ventura, who is leaning with his back against the wall, flanked by a portrait of Hélène Fourment by Rubens, the painter of the Flight to Egypt of the previous shot, and by Van Dyck’s Portrait of a Man.

These three well-known works are specifically situated: we are seeing the walls of the Gulbenkian Foundation, a building that is obviously not in Ventura’s neighborhood. Nothing in the preceding shot announced this visit, and there is nothing in the film to suggest that Ventura has a taste for painting. The director has brutally transported Ventura to this museum, which we suppose by the echoing footsteps and the night light to be empty of visitors, closed off for the shooting of this scene. The relationship between the three paintings and the filmic ‘still life’ that immediately precedes them, together with that between the decaying home and the museum, and perhaps even that between the love letter and the paintings on the walls, composes a very specific poetic displacement, a metaphor that speaks in the film about the art of the filmmaker: of its relationship to the art in museums, and of the relationship that one art and the other forges with the body of its characters. A metaphor which speaks, in short, about their politics.

The politics here might seem quite easy to grasp at first. A silent shot shows us a museum guard who is himself black walk up to Ventura and whisper something in his ear. As Ventura walks out of the room, the guard pulls a handkerchief from his pocket and wipes clean the traces of Ventura’s feet. We understand: Ventura is an intruder. The guard tells him later: this museum, he says, is a refuge, far from the din of poor neighborhoods and from the supermarkets whose merchandise he used to have to protect from widespread shoplifting. Here, though, is an old and peaceful world that is disturbed only by the chance visit of someone from their world. Ventura himself had already manifested that, both with his attitude—he offered no resistance to being escorted out of the gallery, and eventually out of the museum through the service stairs—and with his gaze, which scrutinized some enigmatic point situated, it seemed, well above the paintings. The politics of the episode would be to remind us that the pleasures of art are not for the proletariat and, more precisely still, that museums are closed off to the workers who build them. This becomes explicit in the gardens of the Foundation, in the conversation between Ventura and the museum employee during which we learn why Ventura fits into this displaced setting. There used to be nothing here at all but a marsh, bushes and frogs. It was Ventura, together with other workers, who cleaned up the area, laid down the terrace, built the plumbing system, carried the construction materials, erected the statue of the place’s founder, and planted the grass at its feet. It was here, too, that he fell from the scaffolding.

The episode, in sum, would be an illustration of the poem in which Brecht asks who built Thebes, with its seven gates and other architectural splendors. Ventura would represent all those people who have constructed buildings, at great danger to their health and lives, which they themselves have no right to enjoy. But this simple lesson does not justify the museum being deserted, empty even of those people who do benefit from the work of the Venturas of this world. It does not justify the fact that the scenes shot inside the museum should be so silent; or that the camera should linger on the concrete steps of the service stairs down which the guard escorts Ventura; or that the silence inside the museum should be followed by a long panoramic shot, punctuated by bird cries, of the surrounding trees; or that Ventura should tell his story, from the exact day of his arrival in Portugal, on 29 August 1972; or that the scene should brutally end with him indicating the spot where he fell. Ventura here is something completely different from the immigrant worker who represents the condition of immigrant workers. The greenery of the scene, the way Ventura towers over the guard, the solemn tone of his voice as he seems to recite a text that inhabits him—all of this is very far from every narrative of misery. Ventura in this scene is a chronicler of his own life, an actor who renders visible the singular grandeur of that life, the grandeur of a collective adventure for which the museum seems incapable of supplying an equivalent. The relationship of Pedro Costa’s art to the art displayed on the walls of the museum exceeds the simple demonstration of the exploitation of workers for the sake of the pleasures of the aesthete, much as Ventura’s figure exceeds that of the worker robbed of the fruit of his labor. If we hope to understand this scene, we have to tie the relationships of reciprocity and nonreciprocity into a much more complex knot.

To begin with, the museum is not the place of artistic wealth opposed to the penury of the worker. The colored arabesques of the Flight to Egypt show no straightforward superiority over the shot of the window with four bottles in the poor lodgings of the two workers. The painting’s golden frame strikes us as a stingier delimitation of space than the window of the house, as a way of canceling out everything that surrounds it and of rendering uninteresting all that is outside of it—the vibrations of light in the space, the contrasting colors of the walls, the sounds from outside. The museum is a place where art is locked up within this frame that yields neither transparency nor reciprocity. It is the space of a stingy art. If the museum excludes the worker who built it, it is because it excludes all that lives from displacements and exchanges: light, forms, and colors in their movement, the sound of the world, and also the workers who’ve come from the islands of Cape Verde. That might be why Ventura’s gaze loses itself somewhere in the ceiling. We might think he is envisioning the scaffolding he fell from. But we might also think of another lost gaze fixed on an angle of another ceiling, the ceiling in the new apartment he is shown by a fellow from Cape Verde who in many ways resembles the museum employee. He is, in any case, just as convinced that Ventura is not in his element in this apartment, which Ventura had requested for his fictive family, and also just as eager to wipe clean the traces of Ventura’s intrusion on this sterile place. In answer to the spiel about the sociocultural advantages of the neighborhood, Ventura had majestically extended his arms towards the ceiling and uttered a lapidary sentence: ‘It’s full of spider webs.’ The social-housing employee cannot verify the presence of these spider webs on the ceiling anymore than we can. It could be Ventura who has, as the saying goes, ‘spider webs in the attic.’ And anyway, even if insects do crawl up and down the walls of this housing project, they are nothing when compared to the decaying walls of his friend Lento’s or of Bete’s place, where ‘father’ and ‘daughter’ amuse themselves seeing, as good disciples of Leonardo da Vinci, the formation of all sorts of fantastic figures. The problem with the white walls that welcome the worker to the housing project is the same as the problem of the dark walls of the museum which reject him: they keep at bay the chance figures in which the imagination of the worker who crossed the seas, chased frogs from the city center, and slipped and fell from the scaffolding can be on a par with that of the artist. The art on the walls of the museum is not simply a sign of the ingratitude towards the person who built the museum. It is as stingy towards the sensible wealth of his experience as to the light that shines on even the most miserable homes.

We’ve already heard this in Ventura’s narrative about his departure from Cape Verde on 29 August 1972, his arrival in Portugal, the transformation of a swamp into an art foundation, and the fall. By placing Ventura in such a setting, Pedro Costa has given him a Straub-like tone, the epic tone of the discoverers of a new world. The problem is not really to open the museum to the workers who built it, but to make an art commensurate with the experience of these travelers, an art that has emerged from them, and which they themselves can enjoy. That is what we learn from the episode which follows Ventura’s brutal fall. It is an episode constructed around a double return: the return to Ventura’s reading of the letter, and a flashback to the accident. We see Ventura, his head now in a bandage, returning to a wooden shack with a dilapidated roof. He sits hunched over at a table, imperiously insists that Lento come play cards, and continues reading the love letter he wants to teach to Lento, who can’t read. This letter, which is recited many times, is like a refrain for the film. It talks about a separation and about working on construction sites far from one’s beloved. It also speaks about the soon-to-be reunion which will grace two lives for twenty or thirty years, about the dream of offering the beloved a hundred thousand cigarettes, clothes, a car, a little house made of lava, and a three-penny bouquet; it talks about the effort to learn a new word every day— words whose beauty is tailor-made to envelope these two beings like a pajamas of fine silk. This letter is written for one person only, for Ventura has no one to send it to. It is, strictly speaking, its own artistic performance, the performance Ventura wants to share [partager] with Lento, because it is the performance of an art of sharing [partage], of an art that does not split itself off from life, from the experience of displaced people or their means of mitigating absence and of coming closer to their loved one. The letter, however, and by the same token, belongs neither to the film nor to Ventura: it comes from elsewhere. Albeit more discreetly, it already scanned the ‘fictional’ film of which Colossal Youth is the echo and the reverse: Casa de Lava, the story of a nurse who goes to Cape Verde in the company of Leão, a worker who, like Ventura, has also injured his head, but on a different construction site.

The letter first appeared in the papers of Edith, an exile from the big city who went to Cape Verde to be near her lover, sent by Salazar’s regime to the Tarrafal concentration camp. She stayed there after his death and was adopted, in her confusion, by the black community, which lived off of her pension, and thanked her with serenades. It had seemed, then, that the love letter had been written by the sentenced man. But at the hospital, at Leão’s bedside, Mariana gave the letter to Tina, Leão’s younger sister, to read, as it was written in Creole. Tina appropriates the letter, which becomes for the viewer not a letter sent from the death camp by the deported man, but by Leão from a construction site in Portugal. But when Mariana asks Leão about it, as he finally emerges from his coma, his answer is peremptory: how could he have written the love letter, if he doesn’t know how to write? All of a sudden, the letter seems not to have been written by, or addressed to, anyone in particular. It now seems like a letter written by a public scribe adept at putting into form the feelings of love, as well as the administrative requests, of the illiterate. Its message of love loses itself in the grand, impersonal transaction which links Edith to the dead militant, to the wounded black worker, to the kitchen of the erstwhile camp cook, and to the music of Leão’s father and brother, whose bread and music Mariana has shared, but who would not go visit Leão at the hospital. They continued, nevertheless, working on refurbishing his house, the house which he would not enter but on two legs, all the while making arrangements so that they, too, could go and work on construction sites in Portugal.

The letter that Pedro Costa gives Ventura to read belongs to this wide circulation: between here and elsewhere, committed city folk and exiled workers, the literate and the illiterate, the wise and the confused. But in extending its addressees, the letter doubles back to its origin and another circulation is grafted onto the trajectory of the immigrants. Pedro Costa wrote the letter by mixing two sources: a letter by an immigrant worker, and a letter written by a ‘true’ author, Robert Desnos, who wrote his letter sixty years earlier from camp Flöha in Saxony, a way-stop on the road to Terezin, and death. This means that Leão’s fictional destiny and Ventura’s real one are brought together in a circuit which links the ordinary exile of workers to the death camps. It also means that the art of the poor, of the public scribe, and of great poets are captured together in the same fabric: an art of life and of sharing [partage], an art of travel and of communication made for those for whom to live is to travel—to sell their work force to build houses and museums for other people, in the process bring with them their experience, their music, their way of living and loving, of reading on walls and of listening to the song of humans and birds.

There is no aestheticizing formalism or populist deference in the attention Pedro Costa pays to every beautiful form offered by the homes of the poor, and the patience with which he listens to the oftentimes trivial and repetitive words uttered in Vanda’s room, and in the new apartment where we see Vanda after she has kicked her habit, put on some weight, and become a mother. The attention and the patience are inscribed, instead, in a different politics of art. This politics is a stranger to that politics which works by bringing to the screen the state of the world to make viewers aware of the structures of domination in place and inspire them to mobilize their energies. It finds its models in the love letter by Ventura/Desnos and in the music of Leão’s family, for their art is one in which the form is not split off from the construction of a social relation or from the realization of a capacity that belongs to everyone. We shouldn’t confuse this with that old dream of the avant-garde in which artistic forms would be dissolved in the relations of the new world. The politics here, rather, is about thinking the proximity between art and all those other forms which can convey the affirmation of a sharing [partage] or shareable [partageable] capacity. The stress on the greens of Vanda’s room cannot be separated from the attempts—by Vanda, Zita, Pedro or Nurro—to examine their lives and take control of it. The luminous still life composed with a plastic bottle and a few found objects on the white wooden table of a squat is in harmony with the stubbornness with which the redhead uses his knife to clean, the protests of his friends notwithstanding, the stain from the table destined for the teeth of the excavator. Pedro Costa does not film the ‘misery of the world.’ He films its wealth, the wealth that anyone at all can become master of: that of catching the splendor of a reflection of light, but also that of being able to speak in a way that is commensurate with one’s fate. And, lastly, the politics here is about being able to return what can be extracted of sensible wealth—the power of speech, or of vision—from the life and decorations of these precarious existences back to them, about making it available to them, like a song they can enjoy, like a love letter whose words and sentences they can borrow for their own love lives.

Isn’t that, after all, what we can expect from the cinema, the popular art of the twentieth century, the art that allowed the greatest number of people—people who would not walk into a museum—to be thrilled by the splendor of the effect of a ray of light shining on an ordinary setting, by the poetry of clinking glasses or of a conversation on the counter of any old diner? Confronted with people who align him with great ‘formalists’ like Bresson, Dreyer or Tarkovsky, Pedro Costa sometimes claims a whole different lineage: Walsh and Tourneur, as well as more modest and anonymous directors of B films who crafted wellformatted stories on a tight budget for the profit of Hollywood studios, and who didn’t for all that fail to get the audiences of neighborhood cinemas to enjoy the equal splendor of a mountain, a horse, or a rocking chair—equal because of the absence of any hierarchy of visual values between people, landscape, or objects1. At the heart of a system of production entirely subservient to the profit of its studio heads, cinema showed itself to be an art of equality. The problem, as we unfortunately know, is that capitalism is not what it used to be, and if Hollywood is still thriving, neighborhood cinemas are not, having been replaced by multiplexes that give each sociologically-determined audience a type of art designed and formatted to suit it. Pedro Costa’s films, like every work that eludes this formatting process, are immediately labeled as film-festival material, something reserved for the exclusive enjoyment of a film-buff elite and tendentiously pushed to the province of museums and art lovers. For that, of course, Pedro Costa blames the state of the world, meaning the naked domination of the power of money, which classes as ‘films for film-buffs’ the work of directors who try to bring to everyone the wealth of sensorial experience found in the humblest of lives. The system makes a sad monk of the director who wants to make his cinema shareable [partageable] like the music of the violin player from Cape Verde and like the letter written jointly by the poet and the illiterate worker.

It is true that today, the domination by the wealthy tends to constitute a world in which equality must disappear even from the organization of the sensible landscape. All the wealth in this landscape has to appear as separated, as attributed to, and privately enjoyed by, one category of owners. The system gives the humble the pocket change of its wealth, of its world, which it formats for them, but which is separated from the sensorial wealth of their own experience. This is the television in Vanda’s room. Still, this particular deal of the cards is not the only reason behind the break in reciprocity and the separation between the film and its world. The experience of the poor is not just that of displacements and exchanges, of borrowing, stealing, and giving back. It is also the experience of the crack which interrupts the fairness of exchanges and the circulation of experiences. In Casa de Lava, it is difficult to tell if Leão’s silence as he lies on the hospital bed is the manifestation of a traumatic coma or the desire not to return to the common world. So, too, with Edith’s ‘madness,’ her ‘forgetfulness’ of the Portuguese language and her confinement to booze and Creole. The death of the militant in the camp of the Salazar regime and the wound of the immigrant who works on construction sites in Portugal establish—at the heart of the circulation of bodies, medical care, words, and music—the dimension of that which cannot be exchanged, of the irreparable. In Ossos, there is Tina’s silence, her loss as to what to do with the child in her arms other than take the child with her to their deaths. Colossal Youth is split between two logics, two regimes of the exchange of words and experiences. On one side, the camera is placed in Vanda’s new room, which is sterile white and filled by a doublebed of the type one finds at discount stores. There, a mellower and plumper Vanda talks about her new life, about her detox, the child, the deserving husband, about her treatment and health issues. On the other, the camera follows the often silent Ventura, who now and then utters an imperious command or lapidary sentence, and who sometimes loses himself in his narrative or in the reciting of his letter. It portrays him as a strange animal, too large or too shy for the set, whose eyes sometimes shine like those of a wild animal, and whose head is more often bent down than held up: the distracted gaze of a sick man. The point with Ventura is not to gather the evidence of a hard life, even if it is in order to figure out who cinema can share [partager] this life with, and to whom it can give it back as his or her life. The point is rather to confront what cannot be shared [l’impartageable], the cracks that have separated a person from himself. Ventura is not an ‘immigrant worker,’ a poor man entitled to be treated with dignity and to share in the pleasures afforded by the world he has helped build. He is a sort of sublime drifter, a character from tragedy, someone who interrupts communication and exchange on his own.

There seems to be a divorce between two regimes of expression in the passage from the dilapidated walls, the colorful sets, and the loud colors of the slums to the new furniture and the white walls which no longer echo the words of those in the room. Even if Vanda is willing to play the role of one of Ventura’s ‘daughters,’ even if Ventura sits at her table and chats in her room, and occasionally even does some baby-sitting, the crack in Ventura casts the shadow of this enormous and broken body, this enormous body which has been displaced into the story of Vanda’s new life, on her narrative at the same time that it lends vanity to it. We can describe this intimate divorce using terms taken from on old quarrel, one summed up more than two centuries ago by Jean-Jacques Rousseau in the Preface to The New Heloise. These family letters, are they real or fictive, the objector asks the man of letters. If they are real, then they are portraits, and we expect portraits to be faithful to the model. This makes them not very interesting to people who are not members of the family. ‘Imaginary paintings,’ on the other hand, interest the public, provided they resemble, not a particular individual, but the human being. Pedro Costa says things differently: the patience of the camera, which every day mechanically films the words, gestures, and footsteps of the characters—not in order to make films, but as an exercise in approximating the secret of the other—must bring a third character to life on the screen. A character who is not the director, nor Vanda, nor Ventura, a character who is, and is not, a stranger to our lives2. But the emergence of this impersonal also gets caught up in the disjunction in its turn: it is hard for this third character to avoid becoming either Vanda’s portrait, and as such enclosed in the family of social identifications, or Ventura’s painting, the painting of the crack and the enigma which renders family portraits and narratives futile. A native of the island says as much to Mariana, the well-intentioned nurse: your skull is not fractured. The crack splits experience into those that can be shared [partageable], and those which cannot [impartageable]. The screen where the third character should appear is stretched between these two experiences, between two risks: the risk of platitude, in the life narratives, and of infinite flight, in the confrontation with the crack. Cinema cannot be the equivalent of the love letter or of the music of the poor. It can no longer be the art which gives the poor the sensible wealth of their world. It must split itself off, it must agree to be the surface upon which the experience of people relegated to the margins of economic circulations and social trajectories try to be ciphered in new figures. This new surface must be hospitable to the division which separates portrait and painting, chronicle and tragedy, reciprocity and rift. An art must be made in the place of another. Pedro Costa’s greatness is that he simultaneously accepts and rejects this alteration, that his cinema is simultaneously a cinema of the possible and of the impossible.

1 See Pedro Costa and Rui Chaves, Fora! Out! (Porto: Fundação de Serralves, 2007) 119.

2 Fora! Out!, p.115.