By Jacques Rancière

Published in ‘Short Voyages to the Land of the People’ (Stanford University Press, 2003). French text appeared under the title ‘Un enfant se tue’ in ‘Courts Voyages aux pays du peuple’ (Editions du Seuil, 1990). Translated by James B. Swenson.

A wintry sky above the landscape of a working-class suburb. A woman seems out of place there. Her height accentuates the elegant cut of her coat and the distinction of her gait. She is coming out of an anonymous apartment block, one of those new but already dilapidated buildings where the city’s poor now live. She is waiting for the tram, which takes a while to come. To pass the time, she looks the other way. For the landscape of this anonymous suburb is itself divided. There are the working-class apartment blocks and there are vacant lots along the riverside where wandering children play. The foreign woman stares intensely at a confused spectacle near the riverside. She does not know, we do not know, that at this very moment she is losing her way.

The film is called Europa ’51. The actress who plays the foreigner is a foreigner herself. Her name is Ingrid Bergman. The director, a native who frames the foreigner’s gaze on the suburb of his city, is named Roberto Rossellini. They both know, no doubt, that in filming this scene of getting lost they themselves are losing their way, telling the story of their own perdition, that is, succeeding at the particular form of perdition that is known as creating a work (oeuvre).

How should we understand this perdition? Europa ’51, a film entitled with a place and a date, can easily be described as the representation of a trauma. First of all the trauma of an age and a civilization: the heroine, a rich bourgeoise absorbed by social life, was unable to see the true extent of the effects of this time of war and horror on her son, an impressionable child. The child’s suicide tears her out of the complacency of her universe and sets her on a voyage into the heart of poverty and charity, creating a scandal that will lead her friends and family to have her committed. It is also a properly psychoanalytic trauma, as can be seen through a more precise analysis that shows how the story unfolds according to the rhythm of three identically recurring scenes (1). Three times, leaning over a bed of suffering, Irene, the heroine, finds herself touching heads with someone she cannot have: her son, having survived his fall but succumbing to an overdoes of morphine; a prostitute, whom Irene helps in her death throes; an inmate of the asylum, who has just attempted suicide: the return of a single trauma, of a irreducible real before which Irene is powerless.

But the art of the filmmaker here shows us something more than the troubles of the times and the repetition of the unspeakable. Europa ’51 is a film about events, encounters, and reminiscences, and perhaps also a film about the work (oeuvre) and its absence.

A film about events: a film that is capable of teaching us something about what “something is happening” means. The problem of cinematographic art, as we approach its centenary, can be stated fairly simple: is it possible for something to happen that is not already on the poster? Most often it is enough to see, on the walls of subway stations as the train stops and starts again, the poster that exhibits the low-angle shots of the horror film or the teeming colors of a comedy to know that nothing will happen on the screen that goes beyond the significations that are already on the wall. But here something happens. The film places itself not under the sign of trauma but under the sign of the event, under the sign of the intolerable: a child kills himself. What makes this intolerable is not the repetition of an impotence, but rather the apprenticeship of the unique power that goes forth to meet the event. We can understand this even at the level of the plot: from one scene to the next, from one distress to the next, something new happens, the same trauma is not repeated. The heroine comforts the dying prostitute, whereas her child died alone, by surprise. And she saves her suicidal companion. But this gain in power is above all reflected in her face. The film is the story of a face that reflects, a look that observes and distinguishes, accompanied by a camera that follows the work of reflection. Europa ’51 works on representation, on the way subjects change their manner of being one with their representation. The power that this labor makes evident can be named in good old Platonic fashion: it is the power of reminiscence, of recalling a thinking subject to his or her destiny. This movement of reminiscence is accomplished through he conjunction of three acts, three imperatives set in action: to know what was said, to go see somewhere else, to remember yourself.

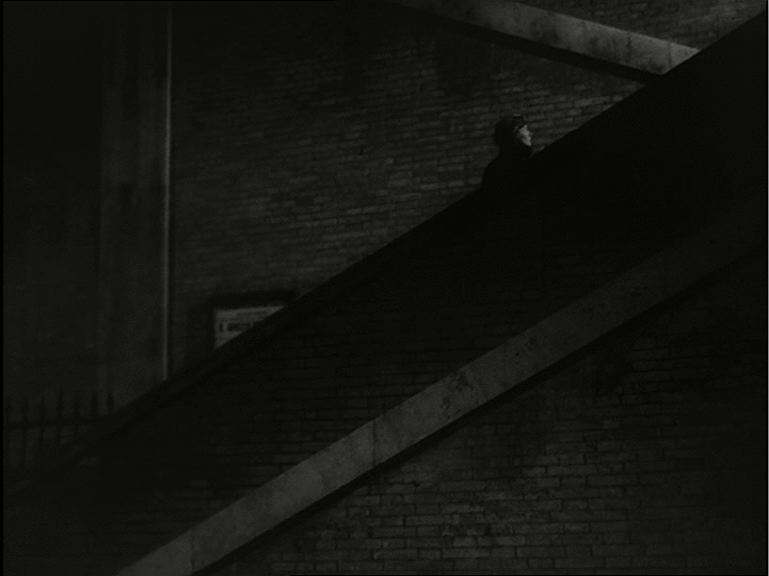

To know what was said: to know how the event consists in saying, in hearing what speaking means. For the event is first of all what relates to the nothing, the niente that runs through the film, said first by the child who has no particular complaint to make, repeated at the end by the mother when the psychiatrist shows her blots to be interpreted and she sees nothing. A scandalous response that provokes the return response: what do you mean, nothing? To see nothing in the image that allows the patient to be diagnosed is to admit to a radical madness. Nothing has neither place nor reason to exist. It is a pure vertigo, a call for the void. And it is indeed the void that is at stake here, just as in another Rossellini film that is also defined by a place and a number, another story about a child killing himself, Germania anno zero. The patricidal child allowed himself to fall into the void, succumbing less to remorse that to vertigo (2). And once again it is vertigo to which the innocent child succumbs, in the emptiness in the middle of the stairwell. The same vertigo, but also a different one: no longer that of the words which made a nation mad, but that of an unspeakable grief. And just like his guilty brother from Germany, he first rehearsed his scene as in a game. In front of the mirror of maternal vanities, in the emptiness that frames her imag, he staged the death act that will throw him into the void with a curtain tie. The event relates to nothingness, to the radical lack of any cause of good cause that would reattach it to the rationality of the profits and losses of a collective trauma; And this is why it can provoke the movement of reminiscence. By slowing it down, Rossellini has here given the event a form that ties it in a singular manner to the labor of reminiscence. At first we think that the child who threw himself into the stairwell is dead, but this turns out to be false. The surgeon reassures us and at the same time the mother about the consequences of the accident. Still, soon afterward, when we hear the nurse talking about morphine at the child’s bedside, we have a premonition of what is to come. But in the entire ensuing scene between mother and child, the camera seems to give the lie to this expectation of death that will later return by surprise. It is the aprés-coup of the event that sets off the labor of reminiscence, a labor that hangs on a single question: “What did he say?” Not: “Why did he kill himself?” The latter is the obscene question, the question posed by the politicians who know in advance why the child killed himself: because there is war, poverty, and the disturbances of the time and of consciences. It is the question posed by people who make knowledge out of what other do not know, and for whom, as a consequence, what happens or what happened is of no interest. Death is enough to set explanation going. There is never a lack of deaths or explanations.

Here something else is at stake. An event has occurred. The child has killed himself or rather fallen into the void, And it is not a matter of knowing why he killed himself, but rather what he said about his vertigo. What sets the heroine, Irene, on the path to her truth is the mystery of the word that the child must have said at the hospital, the words that would have signified his act to her. She goes to ask these words from the one who heard them, her cousin Andrea, the scandalous relative of the family, the communist journalist. She goes to him to know what was said. And of course that means nothing to him. He knows what speaking means. What interests him is what is behind words behind speech, what explains it; behind the individual pain that seeks its meaning in a child’s sentences, the great social pain. Andrea knows the reasons of this pain and he knows that it will not be cured by words.

He will thus proposed another journey to her who wants to know what the child said. He will propose a cure to the suffering mother: to go see, to learn the great suffering of others.

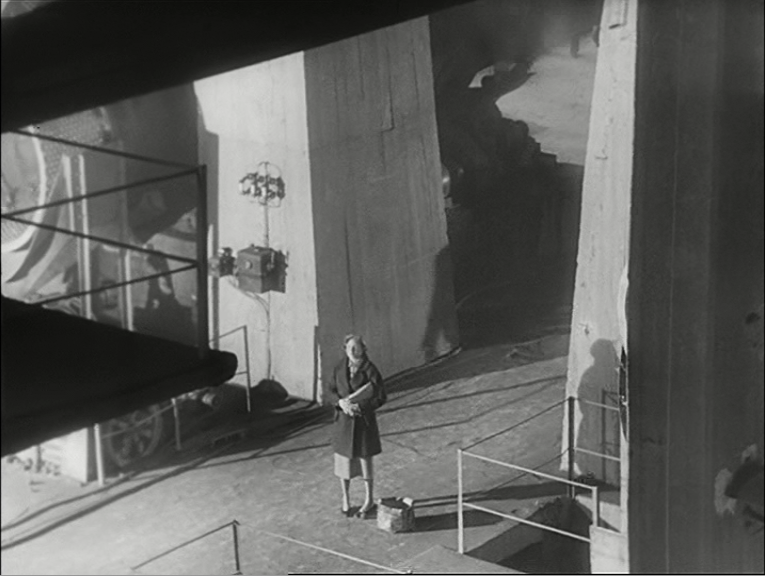

A guided tour. She takes the tram with him to the suburban apartment block where he wants to show her another sick child whose cure depends upon no word, no psychological problem, but simply upon the absence of the money needed for treatment. At the end of the tramway, the people. This is Rossellini’s stroke of genius, compared to the derisory overload of decors and signs, characters and atmospheric effects laboriously set out by so many of his fellow filmmakers to get us to recognize, in family celebrations, at bistros and popular dances, in tender or violent refrains, in postures and accents, the people in person. Here there is neither dancing, bistro, or local color or accent. This last absence can be attributed to an entirely practical reason: the film is dubbed. Just like the fishermen’s wives in Stromboli, these Roman proletarians speak English. The heroes of Roma, città aperta had originally been filmed as if in a silent movie since there was no sound equipment. But the hazards and constraints of production meet up with a more essential hazard and constraint. The voyage to the land of the people, like the voyage to Italy, is not linguistic. In Rossellini’s films the voice does not belong to what is represented, it does not specify a body. The voice is a call or a response. Except that the call is never heard and the gaze must make up for its lack and orient the body towards its place. The voice that counts is the one that accompanies and comments upon this movement. Rossellini can thus dispense with the flavoring of lower-class accents, along with all the other incidental effects, in order to grasp and seize upon the essential: the people are first of all a way of framing. There is a rectangular frame that the camera cuts out: inside this frame there are a lot of people. And that is enough. We have here a necessary and sufficient structure of representation: the people are represented by a frame that encloses a lot of people – a fundamental structure that pays off in sensible qualities that become moral ones, in characteristics of unhappiness that can be exchanged for bursts of happiness: people are crowded together, but that way they can stay warm and maintain solidarity. And, to make the representation complete, there also has to be someone excluded, or, to put it in scholarly terms, there must be a contradiction within the people. And here, in the framing of the people’s aways-open door, a suspicious neighbor appears. Contradiction passes through the field of vision and guarantees it.

This is what a visit to the people is: someone leads you, you take the tram all the way to the end of the line and all of the sudden everything is in the frame: the people, which is a way for many to occupy a little space. For Irene this tour is a voyage to what Andrea knows how to represent, he who teaches what is behind words and on the hidden side of society, the go-between who organizes tours of the people. For her the vision is stupefying: she sees something she did not know about, whose existence she had not even imagined. Among those of us who have studied just as Andrea has, at least some, of course, can recognize things: that is what we could have seen by taking the subway or some other kind of public transportation to the end of the line: in an instant, the frame where there is everything. The people in person is there, we’ve seen them, and theory is right. A certain use of sensory certainty provisionally fulfills the desire to know.

A voyage to the “other side” of society: whose existence is recalled to us from the very first words of the film: if Irene has arrived home late it is because the strikes have made things so difficult. This relation between the two sides, the words that speak this relation, are Andrea’s business. He sends the patient on a cure, offers her a trip – a profitable one – to the other side of society. And he has available what makes the cure an education: the intelligible knowledge of the connection between the two sides. Mettere in relazione, he says, is what matters. The art of the go-between is the art of connection. Irene went to him to find out what was said, but, as we know, this is not what he’s worried about. He is there to unveil. His mastery defines a certain regime of what is represented: there is something to see, something hidden. A double gap converts representation into knowledge: behind the words are the facts that prove them wrong: behind the facts are other words that explain them. The answer to the question “What is happening?” is always already given. There is another place, one which we also know and which is to be found at the end of the tour, when we come back from the tram ride, called the editorial office. There is a corner of a desk in the office, always covered with papers, where a gentleman, whom the employees call dottore, writes down what you need to know to put things in relation. This tinkering at the desk corner has a name. It is called the labor of consciousness (coscienza, he tells Irene over and over). This labor founds a new connection, a new mode of being-together. “We will do it together”, Andrea tells Irene. Nous mènerons la lutte des classes. “We will carry on the class struggle together,” comment the French subtitles. But the struggle is precisely secondary. What Andrea proclaims is what precedes the struggle and gives it its meaning – the meaning of connection. What is essential resides in the relation between the people of apartment block number 3 and the corner of the desk in the editorial office, in the scene of cure and education that passes through the knowledge of the two sides and their connection.

It is with respect to this social scene – this medical and educational scene – that something is going to happen, a second event. Irene is going to see somewhere else. She is going to leave the frame, leave what the dottore, the go-between, knows how to represent. She has gone back to apartment block 3 by herself to see the child who has been cured thanks to her subsidy. This tour has no guide, but it does have a program. Once this program is accomplished she is on her way back to the tram, since she now knows the route. And all of the sudden she turns around. She leaves the frame, although not in the technical, cinematographic sense. The problem is not one of shots and countershots. It is not a problem of camera work, which would still be part of the art of relation. What is at stake here is not the camera but cinema itself. What is at stake is the artist, what the artist as such can show us: not a play between what is in and out of the shot, between voice-on and voice-off, but a hors-lieu, something outside of any place, and the encounter of a character with this hors-lieu, which in subjective terms, is called a conversion. A conversion is not in the first place the illumination of a soul, but the twisting of a body called by the unknown. The artist Rossellini shows us the sensible action of this conversion, the action of a gaze hat turns around and pulls its body along with it toward the place where its truth is in question.

In material terms, Irene has turned around. Down there, by the river’s edge, a confused scene is unfolding. A body is being pulled out of the water and children are recklessly rushing to see what’s going on. Irene responds to the call of a child who risks falling back into the water, but she also responds to the call of the river: less the call of a distance than of a movement away toward her own loss. The call of a hors-lieu, of what was not part of the tour, tipping over into the unrepresentable. All of the sudden space becomes disoriented. The barrack where Irene leads the reckless kids back to a mother, who is as burdened with children as she is unburdened with a husband, cannot be situated in the space of the tour. She has lost the way that led from apartment block 3 back to the tram and the center of the city, back to the other side and the place where the two sides can be related to one another. We are no longer at home in society, in the sort of social home that allows a visitor who has left her onn home and world at the other end of the line to know where she is, to find a place for herself in another’s home.

This is how the madness begins; she takes a step to the side, losing her way. The moment arrives when the call of the void has an effect but no longer makes sense. The time to connect, explain, and heal has passed. Now something else is at stake: to repeat the event, go look somewhere else, see for oneself. This is how one falls into the unrepresentable, into a universe that is no longer the society sociologists and politicians talk about. For there are a finite number of possible statements, of credible ways of putting together a discourse or a set of images about society. And the moment arrives when the border is crossed and one enters into what makes there be sense, which for that very reason does not itself makes sense, so that one must continue to walk under the sign of interruption, at the risk of losing the way. No doubt there are more and less painful ways of getting lost, and not all of them lead to the asylum where Irene will be locked up on account of her inability to explain her conduct, to connect it with a discourse about society. But at the very least they all lead one who has left behind the categories of what can be said about society, about the people, about the proletariat, or some other representable thing of this sort, to the point where what comes back to us from what we say is that no one can see where we’re going.

Walking under the sign of interruption, of the event and the words that having suspended the ordinary course of things, now oblige us to go forward without turning back. Such was already the constraint imposed by the daemonic sign that obliged Socrates to stop at certain moments and then restart forward – start questioning and defying – under the sign of this interruption. At the time of its release, Eric Rohmer hailed Europa ’51 as a modern version of the trial of Socrates. But this socratic presence is not only in the negative aspect of a society that judges and condemns what it does not understand; it is first of all in the relation between the event and reminiscence, in the sign of interruption that sets us walking another way, an interminable walk in the course of which the subject exceeds everything that it intelligibly could be said to be one with.

The conversion thus arrives at the place where the act of “consciousness” ought to have occurred. Measuring this gap also means, for the author of these lines, measuring the gap between two visions of the film. I saw it for the first time a quarter of a century ago, at the time of the great revival or, rather, reinvention of Marxism that is associated with the name of Louis Althusser, who set forth its first tasks: to pay attention to the simple gestures that are so natural that we neglect to reflect upon them – seeing, hearing, reading, writing (3). My ambition was to conceptualize cinematic realism within this framework: not a realism of social content, however, as the gods of the camera who where then honored at the Cinéma Mac-Mahon or in the columns of Cahiers du cinéma where far removed from those shores. The realism I was after would somehow have to bring together Marx’s text with the images of Minnelli’s comedies of Anthony Mann’s westerns. “Realist” mise-en-scène unveiled a determinate world through the sole action of a material system of looks, gestures, and actions that lives, focused on, and dreamed that world; an unveiling without mediation, without any signification imposed from the outside, coming to capture the network of gestures in a register of ideological signifieds. Meaning should have been the physical evidence on the screen of the relations between a certain man and a certain world; it should be entirely produced and manifested by the relations between the characters and their universe.

This is the basis on which I had seen Europa ’51, judging that it was “half of a realist film.” Half of one, I wrote, because the film went awry at the midpoint, precisely when the heroine walked up the steps of a church, after which she would consecrate herself to caring for a tubercular prostitute, the “suspect neighbor” of apartment block 3. Up until that point, I added, the physical evidence of the character corresponded to the social evidence of her experience. A bourgeois woman, displaced from her own world, discovered an unknown territory in which she tried to situate herself through a common system of gestures, the gestures of a mother. Once she had climbed the stairs, she was no longer a character climbing stairs but a saint. The material movements of the body were thenceforth captured by an ideological signification that transformed them into an itinerary toward sainthood and madness, following the famous Pauline equivalence of the cross that is folly in the eyes of worldly wisdom.

Still, seeking to reconcile what I had to say with the resistance the film posed, I had found a solution that I had taken over from an old trick of Marxist aesthetics: as was well known at the time, Balzac, a legitimist reactionary, nonetheless showed us, against his intention and through the force of art, a realist vision of a world that implicitly sapped his reactionary ideology and the ideological foundation of the monarchical order. In the same way, Rossellini the materialist filmmaker contradicted Rossellini the Catholic idealist, showing us something other than what the latter wanted to say. In spite of himself, he gave us every means to understand how this heroine went astray on the path to salvation: not having been able to understand what she saw, to achieve consciousness of the social relations in which she was caught, she fell back into what was sainthood for the Catholic ideologue but that the materialism of Rossellini’s camera revealed to be – for us as for the world, even if in a different sense – madness.

But there was still something in the film that resisted allowing the same trick of “consciousness” that it let us see being applied to it in turn. And perhaps spending a few years at the end of subway lines or in the labyrinth of the archives of worker’s movements was a way of prolonging its effect, of walking under the seign of interruption by holding the artifice of an answer suspended. Seeing the film again after a quarter century, it seemed that the gap that leads to madness or sainthood is not the effect of the stairway that leads from the street of walkers to the church of saint, where the priests on display are filmed without any more complacency than the popes of Eisenstein the dialectician. The conversion is the movement off to the side, the first deviation at the end of the purposeful visit. For she who had been invited to look behind things, the break comes from looking to the side instead. At this precise moment, by her own act, Irene bids farewell to this famous consciousness that she seemed to me to lack. Later still, while talking with Andrea, the man of authorized scandal, he will repeat to her, patting her shoulder protectively, coscienza, conscienza! Irene bids farewell to this consciousness in the Socratic manner: she lets it go. (4) She says good-bye to this consciousness that fabricates itself by tying together representations at the corner of a desk, that goes along at the same speed and with the same repetitive procedures as the assembly line she describes to Andrea. It is thus completely impossible to oppose the lucidity of consciousness to the wanderings of a beautiful soul. If sainthood is shown to be a folly, it is exactly the same way that consciousness is shown to be the homologue of the assembly line, the constrained and repetitive writing of the dottore when she comes back from his visits to the people.

The genesis of sainthood is thus not any revelation in the smoke of incense between the church’s pillars, but the chance of the deviation that afterward leads little by little toward someone we must call our neighbor. Little by little, we have gone where we should not go, where we no longer know where we are. It is in this way that we become foreign to the system of places, that we become the action of our own reflection. Becoming foreign, this “Christain” way of proceeding is still analogous to Socrates’ way, to the atopia that Socrates calls on when Phaedrus, the naive skeptic, asks him if he believes in the fabulous story that tradition ascribes to the place they are walking to. “If I disbelieved it,” responds Socrates – or rather, if I was an unbeliever like our men of science – I would not be an atopos, someone who is dis-placed, an extravagant. Socrates’ response links displacement with belief or, rather, trust (pistis). (5) It is likewise an act of trust that leads Irene out of the frame, displaces her. And her entire itinerary can be placed under these two categories of displacement and trust. It is not that the wind blows where it wills, the point of view of an Augustinian God and the director Bresson. Rather it is that the walker is always right to walk, that one is always right to go out, go see something to the side, continue to walk wherever one’s own steps – and not those of others – lead. All teleologies and all imageries of coming-to-consciousness are founded on the certainty of a distribution: some people’s mission is to speak for others who know not what they do. Such is the philosophy of the desk corner in the editorial office, the point of view of the go-between. A point of view of mistrust: behind things is where their reasons lie. And we know, moreover, what happens, to go-betweens in the end: they change the object of their mistrust. They come to think that the people are not what they are said to be, that we have been deceived about them. And the reason for this deception lies in some unsavory stories behind the scenes, in the back rooms of the workers’ party. The go-betweens denounce them and right-thinking opinion calls it intellectual courage.

In the face of this “courage”, from which all acquiescences are made, the strangeness of faith is first of all that of trust. Trust affirms that no one can see for those who do not see and turn others’ ignorance into knowledge. The problem is not that of knowing what one does. Whatever clever people might think, that sort of knowledge is usually pretty widespread. The problem is to think about what one does, to remember oneself. To the young delinquent whom she allows to flee, Irene says only: think about what you are doing! And he will indeed think about it. Here the morality of the story and the morality of the camera are equivalent: converting one’s gaze means, in the strict sense, practicing a new kind of thoughtfulness or respect. The Christianity of Rossellini the agnostic – and the artist, as such, is an agnostic: he does not express faith; what he does is establish a point of view – this Christianity turns out to be an equality of respect. This aesthetic and ethical practice of equality, this practice of egalitarian foreignness puts into peril everything that is inscribed in the repertoires of society and politics, everything that represents society, which can only be represented under the sign of inequality, under the minimal presupposition that there are people who don’t know what they do and whose ignorance imposes on others the task of unveiling. But the question is not one of unveiling but of encircling. Irene’s gaze encircles. The halo of sainthood begins as the modesty of this labor of attention. A labor that singularizes self and other. The gaze undoes the confusion of what is represented – at the cost, of course, of another confusion, that of social identities whose distinction depended precisely upon the first confusion. The artist’s labor is to focus on the labor of this gaze, to construct the point of view of foreignness: the conversion of a body and the voice that accompanies it. This construction, as we have said, cannot have anything to do with the typicality of the characters or with the production of the linguistic signs of difference. The constraints of dubbing only confirms a well-defined use of the voice. All naturalness and all local accents are banished so that the voice is reduced to its essence: the commentary that every-one can give about what he sees. This commentary does not have an accent, whether English or Italian, bourgeois of lower class, masculine of feminine. This does not mean that it is an indifferently translatable Esperanto, but rather that it is the bearer of the point of view of the foreigner that undoes national, social, and sexual types. The character of Irene simultaneously feminizes the visitor of the poor, Francis of Assisi, and the merchant (whose story gave Rossellini the “idea” for the film) committed to the asylum on account of having denounced himself for black-marketeering. And Ingrid Bergman, the Swedish actress from Hollywood whose voice resonates, in an English immediately translated into Italian, with those words of the converted French Jew Simone Weil – but who is also the sinner who has brought the scandal of adultery into Catholic and familial Italy – carries this gaze of the foreigner to its most extreme radicalness.

It is in the perspective of such a way of looking that the day at the factory, in which Rossellini condenses the experience of Simone Weil’s factory year, is conceived and represented. The heroine does not go to the factory in order to go to the people, to know their condition. She only goes there in someone else’s place, to do a favor for the mother of the errant children, who wants neither to miss out on the chance for a day of love because of working nor to lose her job because of being absent. She goes there as a foreigner in another’s place. In the eyes of those who, never leaving their own home, accuse passing visitors of not knowing how to measure what is meaningful and what is painful for the natives, this is not a good way to know anything. Rossellini, like Simone Weil, has the opposite point of view: the only “natives” are those who have become resigned, who have stopped looking. It is the foreigner’s gaze that puts us in touch with the truth of a world. The factory that Irene visits is the site of an assault much like the one perceived a century before by a cabinet maker playing the foreigner in a railroad shop. “The noise of the foundry; the bitter smell of the coke, the oil spread over all the gears assault the observer’s senses, “ he wrote.(6) What the foreigner perceives, in the noise and dirt of the factory, as the intolerable itself, is the assault upon the gaze. The factory is in the first place an uninterrupted movement that hurts the eyes, that gives you a headache. It is a constant and unceasing procession of sensory shocks, in which, along with the ability to look, the possibility of thoughtfulness and respect is lost. Irene will again find this same system in the electroshocks of the asylum. In any case, the asylum works just like society. In more or less gentle or violent forms, there are two fundamental techniques of society described by the film: shock and interpretation. On the one hand, the movement of the assembly line and the bursts of electricity; on the other, the Rorschach blots – the nothing that you have to say something about – to be interpreted, and the system of explanatory attributions and inferences that make up the audible discourses of the social, that create society. The factory, the newspaper, and the asylum weave together this rationality. The judge and the priest order is to acquiesce in it.

What is at stake in the struggle going on under our eyes is precisely the effort to liberate the gaze from the assault that both shock and interpretation lay to it, to restore to it the sovereignty that allows it to act, to determine the proper gesture. What sort of gesture should be made is the object of a nocturnal discussion between Irene and Andrea on the piazza of the Campidoglio. Irene has come to ask what the child said. Andrea turns back on her the stereotypes of explanation: the war, the world in ruins, and the disturbance of consciences. But Irene already knows that she must interrupt him and give another response: there is something else to be done, a gesture that she has not accomplished. Now, this question of the gesture is placed under the most august patronage possible: the equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius, the imperator above all others, the stoic emperor, master of himself and the world. In front of this same statue, a hundred years earlier, another foreigner had stopped to meditate upon the virtue of the proper gesture, of the imperial sign: “In the center of the square stands a bronze equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius. The attitude is perfectly easy and natural: he is making a sign with his right hand, a simple action that leaves him calm while it gives life to the entire person. He is going to address his soldiery, and certainly because he has something important to say to them.”(7) This little gesture, this simple action that leaves the actor calm, is for Taine the mark of the antique simplicity of both generals and sculptors, as opposed to the modern universe where prices are on display and artists have all agreed to reproduce the commonly distinguished air of horses and horsemen. A world of distinction and representation, of warm coats and rain boots, of nervous, feminine sensibility and dilettantes who avoid popular vulgarity for lack of knowing the gesture that makes the people peaceful and attentive.

Rossellini’s film could be described thus: the history of a gesture, the gesture that brings peace and salvation, the gesture that failed at the beginning but will succeed at the end. How can we accomplish this little action that leaves calm and brings peace: a peace which is, of course, opposed to the techniques of pacification that stem from shock and interpretation. There is a gesture to be found, a right way of setting one’s head against the head of someone else who is suffering. For it is precisely not the same thing, the same trauma, each time. The gesture is adjusted and gains in power, culminating in a final, scandalous, and atopian gesture. In the final shot, the madwoman enclosed behind the bars where neurotic women are treated makes a sign from above, like the imperator, but behind the bars of her window, to the people from the working-class suburb who have come to see her. Quite simply, she gives them her benediction. The correct gesture is the end of the journey, the memory of a wandering astray that has become an act of peace. In the asylum, as elsewhere, there is the possibility of peace in the face of the techniques of pacification, the possibility of remembering oneself by becoming a foreigner.

Here the question of the correct gesture doubles back on itself. For the artist, the correct gesture, barely perceptible on the screen, marks the gesture of the saint that resumes the line drawn by the event and its reminiscence. The question is one of mastery, of the imperium that the filmmaker exercises over the production of meaning. What is naturally evoked at the foot of the statue is the image of the filmmaker-imperator Eisenstein: he who moved statues, bronze horsemen or Odessa lions. But the distance between Eisenstein and Rossellini is immediately apparent: here mastery is not the art of animating stone in order to mark the downfall of the idols and the passage of History. Rather, in its absolute fragility, it is the irremediable exactitude of the gesture, the outline of the ineffaceable, in which the fulfilled destiny of the saint – the madwoman – and the success of the work – its cruelty – reflect one another.

For there are two figures of the irremediable. On the one hand, there are those that give weight to the social: the images filing past on the screen, the incessant movement of the assembly line: the cement bags in the factory, the pages spilling out of the go-betweens’ rotary presses. The images and bags go by relentlessly. This is what is called reality. Unavoidable, they say. At most you should set aside the torn sack or the unclear image, shelve the explanation that has passed its day. On the other hand, what is irremediable in the work is the risk of there being no return, the cruelty taken on by the fiction: a child kills himself. Not “a child is being beaten,” the fantasy of the family romance whose workings are explained by psychoanalysis. Still less the politicians’ fiction of the massacre of the innocents that calls for inquiry and judgment. “A child kills himself” is the fiction of vertigo, the fiction that is crueler than any other – that is, the fiction of the work as cruelty: the stroke of the irremediable that cuts again and again into the pain of the family romance. Thus Rossellini has the child – the little Romano taken from him by illness – kill himself, throw himself into the void twice: first in the ruins of Berlin, and a second time in the Roman apartment that used to be but no longer is his. The limit-fiction is that of the work in general. For there to be a work, a child has to kill himself, a childhood has to be put to death. And the childhood that is put to death has to lose itself in the absolute risk of the work consecrated to the production of what is barely perceptible. The singular power of Europa ’51 consists in the exact conjunction between the cruelty of the fable and the cruelty of the work, in the coincidence represented between the work’s fiction and its ethic. We should not understand this to mean the classical mastery that transforms the law of composition of the work into the subject of its fable, but rather the absolute dispossession that brings the scandal of sainthood and the perdition of the work back to their common origin and discrepancy: the material inscription of what has no place in the system of reality, the rigorously material dispensation of the immaterial that, in art as in religion, is called grace.

From the labor of the artist who wonders and asks us whether sainthood is still possible, there comes another question, a sister question concerning the possibility of the work: how can the incessant production of the social, the law of shock and interpretation, still authorize a work? What sort of cruelty can the artist still allow himself in a world that allows less and less place to atopia? I spoke about dates: the one that gives the film its title and that of a first viewing at the beginning of the 1960s. What was feverishly developing among us at that time was an activism convinced of the urgency of learning to read, see, listen, stop images and turn them around, and dig underneath words and between the lines – the moment of structuralism, the Marxist revival, semiology, and the nouvelle vague. Now, seeing this dated film of Rossellini’s again today, this film of the postwar years – the age of the great humanist narratives and questions about the human condition and the destiny of the world, but also the triumph of cinema as an art and means of expression – the film seems to attack us from the other side and point up that frenetic critique of words and images as a labor of mourning. As if we had started wanting to read and see, started learning to read and see only when such things were entirely taken up in the system of shock and interpretation and already had no more importance. Our generation staked its battle on the theme: stop the images, as if it were a question of courageously opposing their projection, the captivating shock of stimuli. But shock was already accompanied by interpretation: the couple was installed as a dominant system of representation, and no doubt our enthusiasm, even as we wanted to be critical, helped install it in this domination. We know today that criticism of images is vain because the image appears already escorted by its criticism, affected by its mark of distance and irony. In vain do well-meaning souls bemoan the fate of children who are stupefied by overexposure to televised images. But the child who watches television gets the socialized procedures of criticism at the same time he is assaulted by the shock of the images. Training in the incessant production of images is also a training in criticism as a complementary social activity that derives from the same regime of representability. The flood of criticism is exactly contemporaneous with the flood of images. Demystification is part of stupefaction, of an investing the system of places and ways of occupying them that excludes only one thing: atopia.

Perhaps the duality, the divided destiny of the “nouvelle vague” of the 1960’s can also be understood in this double scansion. On the one hand, the nouvelle vage represented a liberation of the camera, which became the witness of a universe in which figures, spaces, and codes were joyously cut loose from their moorings; running and sliding, disguises and pantomimes and ludicrous encounters, offscreen voices and false match cuts, white painted walls of apartments for young couples and Mediterranean honeymoons… A particular kind of play was established between Godard’s incongruous indoor cycling exercises and the Club-méditerranée drunkenness of Corsica, where the camera of Adieu Philippine followed secretaries running away from the office and from morality: a particular communication between the iconoclastic ambition to undo the codes of representation, the relations between images and words, and the liberated morals of the new social figures advertising happiness: sun on demand and sex without worry. The nouvelle vague’s devotion to Rossellini prevented us from seeing the gulf separating two universes and two regimes of representation. The liberated camera of the nouvelle vague both established and reflected a space where transversals became the norm; where incongruity took the place of the event, where drifting took the place of atopia and iconoclasm that of scandal. The figure of the foreigner who brings scandal with her, stepping off to the side, meeting with the unrepresentable, all fell back into the past and became incomprehensible to a generation that did not recognize any prohibited social or sexual relationship, any relation between words and images that could not be played upon within the frame of the continuous hustle and bustle of representation. Just as there were no sunny beaches where the Club could not take you in the middle of the winter, there were no points of representation that could not be connected by a match cut. It was the time of the eternal possibility of a supplement: threesomes and match cuts. The mirage of the 1960s: that of a society governed only by the pleasure principle, in which, by the same measure, there was no longer any place for the work’s cruelty: the cruelty of a child killing himself or that of a mother’s perdition.

Of course the pleasure principle never reigns alone. On the other side of the impossible atopia, opposite the liberated image and the vagabond representation of new happiness in the winter sun, another figure of iconoclasm arose: no longer the pleasure of incongruity but the labor of criticism; no longer the freedom of representation but the suspension of representation, its exhibition on a screen turned into a blackboard, governed with circles and arrows, its tricks forever pointed out, the match cut played back over and over again to demonstrate its falsehood. No longer the guilt-free morality of grown-up children but the guilt politics of well-educated young militants, which never stops warning you to beware of the way words are tied to images and illustrates this with self-criticism. The best example of this is the path of Godard’s career and the insistence of films like Ici et ailleurs on dismantling the traps of sound and image by which we love to be fooled. The pregnant Palestinian militant dedicating her child to the revolution was actually a Lebanese actress who was not expecting a child; if you could understand the language of the Palestinian guerrillas, you would know that they were not talking about the revolution or the class struggle, as the commentary overdubbed their words, but simply about where to cross the river.

How rigorous this pursuit of lies might be, who can fail to see its price? As the lie is tracked down, the truth gets reduced to the question of place, the certainty of the right place. The disappearance of the child, the going-astray of the mother were only the actress’s lies – political and theatrical lies – in opposition to the authenticity of a place that found a way to speak itself in its own language. Thus was established an infinite deferment between an impossible morality of the camera and an impossible morality of politics. The passion to stop the image became the passion play of the work’s death. As if the age of the work had come to an end with the age of scandal, closing, in the final image of Europa ’51, with the gesture of benediction and farewell given by the foreigner, the saint, the madwoman. As if the moment of her imprisonment had begun the age of absence of the work balanced between the hedonism of images and the archeology of imprisonment: the age of mimetic radicalness, in which a certain idea of happiness and a certain idea of unhappiness can no longer find a meeting point; in which the work’s labor of mourning can only be thought of as that which accompanies revolutions, before being thought of as the mourning for revolutions themselves.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Notes

(1) Alain Bergala, “Roberto Rossellini et l’invention du cinéma moderne,” preface to Roberto Rosselini, Le Cinéma révélé (Paris: Editions de l’Etoile, 1984), p. 11.

(2) Cf. Jacques Rancière, “La Chute des corps, Physique de Rossellini,” La Fable cinématographique (Paris: Editions du Seuil, 2001), pp. 165-85.

(3) Louis Althusser, “From Capital to Marx’s Philosophy,” Louis Althusser and Etienne Balibar, Reading Capital, trans. Ben Webster (London: Versi, 1979), pp. 15-17.

(4) In Greek: Ea Chaïreïn, an expression habitually used by Plato at certain strategic moments of the Socratic dialogues, in particular Phoedo 63c and Phaedrus 2302.

(5) Plato, Phaedrus 229c.

(6) Gabriel Gauny, Le Philosophe Plébien (Paris: La Découverte/Presses Universitaires de Vincennes, 1983), p. 52.

(7) Hyppolite Taine, Italy: Rome and Naples, trans. J. Durand (New York: Leypoldt and Holt, 1869), pp. 109-10.