“Free is complementary. Free is not the opposite of pay. We see there is no cannibalization with free.”

— Jamendo CEO Laurent Krantz

“There’s a set of data that shows that file sharing is actually good for artists. Not bad for artists. So maybe we shouldn’t be stopping it all the time.”

— Douglas Merrill, EMI’s newly appointed president of digital music group

There are several reasons why it’s interesting to look at the evolution of music production, distribution and consumption, as a way of trying to grasp the development of new socio-cultural as well as economical paradigms in the context of network culture. First of all, music, as a means of cultural expression, discloses itself as universal meaning. It has captured all angles of the world, embraced people’s lives regardless of culture, place and time. It might well be a language in its own right. As Anthony Storr once wrote: “Music exalts life, enhances life and gives it meaning. It is both personal and beyond the personal, it remains a fixed point of reference in an unpredictable world. Music is a source of reconciliation, exhilaration and hope that never fails.” Music is primarily held to be a phenomenon that is physically experienced, as if the listener is filled with sound. So I guess it is quite unique since it does not simply bring an external symbol to the attention of the listener, but rather gathers meaning from within the listener him- or herself – It’s not music as a representation of some other idea or expression that generates meaning. In the past, it was as much a social event as a purely musical one: before recording technology existed, you could not separate music from its social context. But since the rise of the music industry, along with the institutionalisation of Western copyright law – emphasising limited duration, fixation and the action of individual authors rather than collectives – musical expressions have increasingly been “de-socialised” (see also previous post). Music — or its recorded artifact, at least — has become a product, a thing that can be bought, sold, traded, and replayed endlessly in any context. In his Noise: The Political Economy of Music, Jacques Attali famously commented that “never before have musicians tried so hard to communicate with their audience, and never before has that communication been so deceiving. Music now seems hardly more than a somewhat clumsy excuse for the self-glorification of musicians and the growth of a new industrial sector”. But, there are stonger forces at work, as David Byrne notes in his nice article in Wired, “this upended the economics of music, but our human instincts remained intact (…) We’ll always want to use music as part of our social fabric: to congregate at concerts and in bars, even if the sound sucks; to pass music from hand to hand (or via the Internet) as a form of social currency; to build temples where only “our kind of people” can hear music (opera houses and symphony halls); to want to know more about our favorite bards — their love lives, their clothes, their political beliefs. This betrays an eternal urge to have a larger context beyond a piece of plastic. One might say this urge is part of our genetic makeup.” And now, as almost everybody seems to agree, it’s time to get rid of the business models that kept the music bizz hostage for so long. The traditional record companies are under crossfire. A deep distrust – to put it mildly – has settled in as a direct consequence of the past decennium of arrogant efforts of “putting the genie back into the bottle”, while demonizing their own customers, the people whose love of music had given them massive profits for decades (including, very recently, wonderful services like Oink, a popular and very efficient torrent site that was specialized in music or, indirectly, also Sonific, a streaming music widget that had to close down due to a “unworkable” music licensing scenario. As founder Gerd Leonhard stated: “we neither want to engage in so-called copyright infringement nor do we have millions of dollars available to buy our way in when it is abundantly clear that doing business under the existing rules of the major labels will simply amount to economic suicide”). Not that music bizz bashing is anything new: musicians like Steve Albini have been fulminating for quite some time now, and they have been right. Tom Waits once remarked that “People are so anxious to record, they’ll sign anything (…) like going across the river on the back of an alligator.” But why would these alligators care about some bad vibes or discontent musicians? They had it all under control. But now, the heat is on, more than ever. What has been obvious for some for years, has become an issue that has spread over the media like a virus. Recently an article in the Wall Street Journal concluded that “for all the 21st-century glitz that surrounds it, the popular music business is distinctly medieval in character: the last form of indentured servitude.” In a talk with David Byrne about the major labels, Brian Eno said: “Structurally, they’re much too large, and they’re entirely on the defensive now. The only idea they have is that they can give you a big advance — which is still attractive to a lot of young bands just starting out. But that’s all they represent now: capital.” And In January the Guardian published a poisonous article by Simon Napier-Bell, who has been working in the bizz for over 40 years, as manager of the Yardbirds, Japan, Boney M and Wham!, amongst others. He stated: “Artists were never the product; the product was discs – 10 cents’ worth of vinyl selling for $10 – 10,000 per cent profit – the highest mark-up in all of retail marketing” and “for 50 years the major labels have thought of themselves as guardians of the music industry; in fact they’ve been its bouncers. Getting into the club used to be highly desirable. Now it doesn’t matter any more.”

It doesn’t matter anymore, since recording costs have declined to almost zero, just like manufacturing and distribution costs. Musicians are increasingly able to work outside of the traditional label relationship, experimenting with online distribution, like Radiohead of course (albeit their stunt seems to have been more of a marketing gimmick), Trent Reznor and so many other less-houshold names (see previous post), or just defecting major labels, and getting in bed with… concert promoters (Madonna left Warner Bros for Live Nation – a spinoff of the much disliked Clear Channel. For a reported $120 million, the company — which until now has mainly produced and promoted concerts — will get a piece of both her concert revenue and her music sales. Recently also Jay-Z defected his longtime record label, Def Jam, for Live Nation, for a roughly $150 million package, that includes financing for his own entertainment venture, in addition to recordings and tours for the next decade) or … coffee houses (since last year Starbucks’ label, Hear Music, has signed singer-songwriters like Paul McCartney, Joni Mitchell, James Taylor and Carly Simon, but last week the label has been turned over to Concord Music Group) and/or other commercial companies and media ventures (Groove Armada with Bacardi, for instance, Prince with The Mail on Sunday, or Junkie XL with game publisher Electronic Arts). It’s becoming a business on itself: Harvest Entertainment is just one of the start-up companies which partners brands with musicians, like, in their case, Placebo or Madness). Labels as we know them now WILL disappear, as the roles they used to play get chopped up and delivered by more thrifty services. Musicians themselves can not only use their own site or MySpace (who don’t pay royalties, by the way) to promote and distribute their music, but also various services like Tunecore, the Orchard, Speakerheart, CDBaby, Nimbit, Snocap, Musicane, INDISTR or AmieStreet (interesting enough they use demand-side dynamic pricing to sell its music. Amazon is one of their investors) – see Coolfer for more examples. “On demand” services like Rhapsody (owned by RealNetworks, recently partnered up with Yahoo Music Ulimited), Napster (which paved the way for P2P, but now a pay service, owned by the Private Media Group, an adult entertainment company) or (maybe) Total Music (a new service by Universal, announced in october 2007) are also dipping, be it very carefully, their toe into the future of the so-called “Music 2.0” (yeah, we like buzz words). According to Gerd Leonhard, the author of The Future of Music and the new book Music 2.0 (downloadable on music20book.com), the music bizz, or the creative producers themselves, should try to monetize the existing behaviour of the user, and metering the use of music on a per-unit base (as iTunes does) is no way to do that. Music should be like water, he says: on tap. You can get as much as you want and you will not have to pay by the song. Want more music? Just ask and listen to it. This is one of the reasons why DRM is being abandoned. Even among the most conservative jackasses in the business it is being being admitted that it is a very ludicrous idea that you cannot share music, which is by many considered to be an essence of music. There is active discussion about flat-fee structure for music at major labels where once this idea was laughed out of the offices (hell, some even start to see positive aspects in P2P file sharing – see quotes in the beginning of this piece). You can now purchase MP3 files for download without DRM from all four major labels on Amazon, emusic and a growing list of music destinations, including the new MySpace Music service. The predictions that an unprotected format would kill sales have simply not been true. But subscription and licensing services are just one possible model. After all, there are lots of indications that the Internet really demands a “free” business model (I posted about Chris Anderson’s “free” models before. However, “free” doesn’t imply that everything should be given away for free – be aware of the “web 2.0” rhetorics! See for example the arrogance of Rupert Murdoch’s MySpace). In this idea of network culture content flows “freely” in abundance, and “attention” is the (yet another) new buzzword. As Kevin Kelly wrote: “copy of digital content will most likely be free or feel like free (…) the key is to offer valuable intangibles that cannot be reproduced at zero cost”. This is about creating values through ubiquity, not through scarcity.The print world already gave up their subscription models and developped new business models, based on free content and online advertising. Page views are worth a lot more to an advertiser than the amount you can get someone to pay for a subscription to them. The way media is consumed online, via search and social distribution, requires that the content is free to distribute and consume. This is why, as Fred Wilson writes, the “discovery/nagivation” layer, on top of the content layer is so important. It’s in services like last.fm (see earlier post), pandora (kind of personalized radio, streams custom listening channels based around a listener’s favorite band or song, using advertising revenue to pay for it), the hype machine (blog search & listen), and playlisting services like project playlist (now being sued by the labels.. sigh), iMeem (now being sued… sigh. update: was being sued, but now seems to have deals with the labels, see comment below), Mixwit, Mixaloo, Muxtape, Songza or Alonetone (I’ve written about some of these exciting ‘virtual’ mixtape machines before. I guess it’s just a matter of time before they will be targeted by RIAA & co. as well). It’s also gonna be in Bill Nguyen’s lala.com project, that mixes social networking with music trading and buying, and is now setting up a new service that will offer unlimited on-demand streams of music (update 29 May: Lala has a new plan: selling song streams for 10 cents a piece. One reason for Lala’s change in direction is that the idea that free music can be used to promote music purchases is fading in general) Qtrax is another ad-supported venture, that promises a “legal” P2P music jukebox, with free downloads for its users (so far Windows only, I’m afraid). In March Qtrax has begun to sign contracts with some major record companies. It seems that the service uses DRM, to help prevent songs from slipping onto “unauthorized” networks, and establish the play counts that will help to figure out how much to pay artists, labels and publishers.

But, not surprisingly, the most exciting initiatives might actually come from independent labels and music-loving individuals and collectives. The blogosphere is of course a matrix of micro-music-channels that are ‘narrowcasting’ their longtailing creations and findings – be it podcasts of eclectic, genre-bending music mixes, or digital rips of out-of-print or hard-to-find records (check out Mutant Sounds, FM Shades or – thanks Bongo Man – awesome tapes from africa) – to their hungry subscribers using MediaRSS (widgets are used for further (re)distribution). You’re interested in Central European Polka, Japanese psychedelic music, or electronic music from the Middle East? No doubt there’s a blog somewhere out there where you can discover and download stuff you haven’t even dreamt of. These “BlogJ’s”, muses Paul Resnikoff, are the “digital-age editions of ‘analog’ radio personalities such as the BBC’s John Peel (rip) (…) Hundreds of niche-obsessed BlogJs will emerge, becoming trusted opinion leaders that will draw 10s if not 100s of 1000s of networked music fans that will discover new music this way – strictly by lifestyle i.e. genre and sub-sub-sub-sub genre. Much like it used to be in music-television; coolness and credibility will rule here.” It’s interesting how these blogs are amalgamating with, sometimes integrating into social networks. Like Stereogum, a bit of a gossipy music blog, that recently gave away OKX: A Tribute to OK Computer and just started up Videogum. Or, more to my taste, RCRD LBL, an ad-supported blog annex label, founded by Peter Rojas (Gizmodo and Engadget ) and Josh Deutsch (Downtown Records). The site offers free MP3 downloads with a description of the bands and songs from its own artists, plus selections from its partner labels (such as Warp, Kompakt and Ghostly). The site has widgets for playlists, photos, tour dates, and fans and the site has a social networking aspect too, in that you can create a profile and become a fan of a band. Peter Rojas in an interview with Wired: “It’s something I’d been kicking around for a while, as someone who loves music blogs, and saw why it had been so difficult for them to become a real business. And I think the biggest reason is that the music on them was very rarely legal. And labels have seen the value in getting the music out there on music blogs, but I thought it was an opportunity to take things to a different level and try to help the artists participate in the upside of creating a site that has an audience (…) I think that’s an important thing about blogging in general, or niche media, is that you have to be honest about who you are and what you’re about and who you’re doing this for. This isn’t meant to be the be-all-and-end-all of the music industry, it’s just meant to be a great place where people who are into this kind of music can get it from those kinds of bands”.

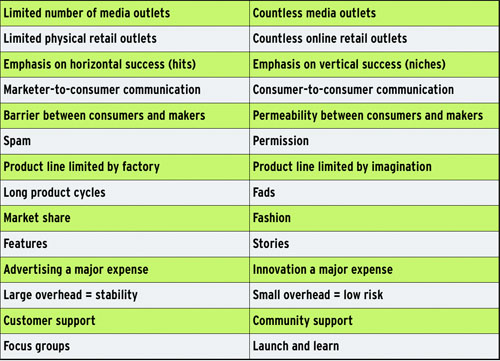

All hail to subjectivity and transparancy. All hail to trust and openess. Seth Godin might be right when he argues that the music bizz isn’t about A&R or brand management anymore, but more about tribal management: “make the people in that tribe delighted to know each other and trust you to go find music for them. And, in exchange, it could be way out on the long tail, no one wants to be on the long tail by themselves, the polka lovers like the polka lovers, they want to be together. But that you, maybe it is only one person, technology makes this really easy, your job is to curate for that tribe. And if you can curate for them guess what the [musical] artists need…you! Guess what the tribe needs…you! You add an enormous amount of value by becoming a new kind of middleman (…) The internet is the ability to get any song you want in front of the people who want to hear it with huge reach and no barriers. What matters isn’t how many, it’s who”. (see Godin’s schedule below for a nice overview of paradigm changes). Of course Musicians themselves try to manage their own “tribes”, via social networks like MySpace or Facebook or their own controlled (boutique) spaces, like Radiohead’s Waste Central, 50 Cent’s This Is 50 or Kylie Minogue’s KylieKonnect . An interesting model is Einsturzende Neubauten’s neubauten.org supporter project (in phase 3 now), an attempt to continue producing music through online support of fans, who for a financial contribution, can interact with the musicians (and other supporters) and get loads of exclusive stuff: not only CD’s and DVD’s, but also webcasts which provide insight in “the working process of the band at rehearsals and recording”. Other musicians rely on their fanbase or community to get their own e-hustle on, like MC Hammer’s DanceJam, Ice Cube and DJ Pooh’s UVNTV, or WeMix.com, founded by Ludacris’ company Tha Peace Entertainment, that wants to be a “user-generated record label”, where artists can join the community, upload their creations, collaborate digitally with fellow artists and have the potential to sell their work (“Top-rated performers become eligible to bypass the traditional A&R process and collaborate directly with Ludacris and other top music stars, thereby creating an entirely new way to launch a career”). But this tribal management approach is also part of P2P file-sharing services, like the now defunct Oink, that allowed users to connect similar artists, and to see what people who liked a certain band also liked. Similar to Amazon’s recommendation system, it was possible to spend hours discovering new bands on Oink. Some services are trying out similar (though legally and industrially approved) approaches, like I Think Music, an online network of indie bands, fans, and stores, which enables them to create and sell a catalog of music to the public, manage and display content online, network between buyers, sellers, and creators of music, as well as manage revenues from the sale of digital music files. It’s basically an experiment in trying to digitally emulate the romantic views of the good ol’ A&R and retail experiences (which, as the relative success of New York City’s Other Music shop prooves, is still as valuable as ever. What they offer is specialisation and quality control, resulting in a trust relationship – see also online shops like the great Boomkat). ithinkmusic.com supplies the tools to build your own online retail shop (like Liquid Crunch did, for example), without all of the headache of stocking, shelving, cataloguing, orders, returns and the general day to day business of running a physical shop. Magnatune is yet another project that is really trying to regain a trust relationship with consumers as well as musicians — its tagline is “We are not evil”. Magnatune makes non-exclusive agreements with artists, and gives them fifty percent of any proceeds from online sales or licensing. Users can stream music in MP3 format (no DRM) without charge before choosing whether to buy or not. Most controversially, buyer can determine their own price, and may download music they have purchased in WAV, FLAC, MP3, Ogg Vorbis and AAC encoding formats. What’s more: all of the tracks downloaded free of charge are licensed under a Creative Commons “by-nc-sa” license, which allows sharing, and non-commercial use for free, as well as new works to be created as long as they are also licensed under the same CC license (Magnatune maintains close organizational ties with the ccMixter project). You can get more CC music via CommonTunes, a listing of user-submitted freely-available music from all over the web, searchable and tagged by keyword. More music aggregating is being done by CloudSpeakers (founded by Adriaan and Chris Bol, based in the Netherlands), a “music-oriented news reader on steroids, backed by a social network where users can build profile pages, add media from the site to them, leave comments, and so on” and MusicBrainz, a project that aims to create an open content music database. Similar to the freedb project, it was founded in response to the restrictions placed on the CDDB, and aims to become a kind of structured “Wikipedia for music”.

All these applications and services – and there are many more out there – are just some of the pieces of a big puzzle that will define the future of the way music (and media in general) is going to be produced, distributed and consumed, and while puzzling we’ll discover that there is not one model, but many different ones. The music industry is rapidly undergoing a process of “Creative Destruction“, a process that might eventually lead to an abundant, open and transparant music business where all the music is available to everyone and discoverable via search and social discovery. What matters now, in the words of Gerd Leonhard, is that “the music industry is in the throngs of this powerful shift from ‘having distribution’ as a gatekeeper to ‘having people’s attention’ as the holy grail. It boggles the mind, but it is now no longer relevant (or shall we say… sufficient) to have distribution, i.e. to have a replication facility, a retail network, reserved shelf space at the point-of-sale, or frequency slots (if you are radio company), or a satellite in orbit, or a cable network – what really matters is how many people care about what’s IN your network!”

PS: Leonhard has also another, pretty scary take on what the future may bring, influenced by Cory Doctorow’s Overclocked.

(image on top uploaded by Lady Pain, found on the blog of Fred Wilson)