By Louis Skorecki

Originally published as ‘Qui était Stavros Tornes ?’ in Libération, August 1988. Revised and extended version of the translation made by Marios Karamanis. Two of Stavros Tornes films will be shown during the Courtisane Festival (17-21 April 2013), as part of the programme “Once Was Fire”.

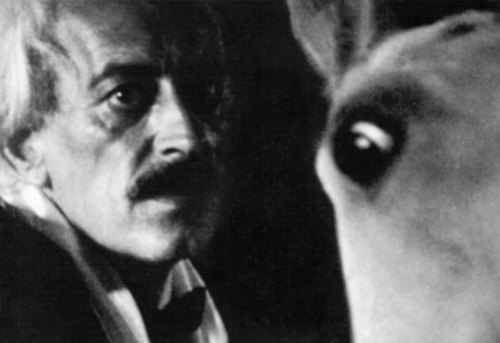

This man has died. Artists die as well, even the greatest ones. And Stavros Tornes – this is the name of this man, a Greek, we can see him in his 1982 film Balamos, alive and well, even more hallucinating than the crazy horse he’s holding on to – this man has died.

Every death is a scandal, but his was inadmissible. Stavros Tornes did not have the right to die. He allowed himself to. He probably had his reasons, but he should have remained eternal.

And the strange thing is, he could have.

Stavros Tornes was a filmmaker. A word which today sounds like an insult, a curse, an impudence. This is normal: it is used to point out frauds. This era definitely belongs to television (so much the better), and since quite some time the concept of cinema has been taken over by makers of video-films, TV-films, whatever-films.

He was a filmmaker. That was all he was. Poet, philosopher, prophet. But poet in cinema, prophet of images / messages for the planet.

He was today’s greatest filmmaker. He died in the anonymity he had chosen, conscious of being an animal on the way to extinction, survivor of an advanced era in which the words art and cinema, artist and filmmaker were not yet swear words.

He was young; 56 is childhood for a filmmaker. But to be the greatest and yet unknown is exhausting. It exhausts quickly and hefty, even if one has chosen to remain unknown in order to be able to continue to make films.

Every second Stavros Tornes was aging one hour. Tormented by the agony of cinema, he was dying of desire – love – to resurrect it, be it at the cost of his own destruction. To give his life to the woman cinema, and die.

Exhausting his body by feeding on anything – a poor man’s philosophy. Without asceticism or any other crap. Without alibi. Without support. Excluded, marginal, road companion of all the squatters of the post-industrial society, of all the vagabonds of the urban delirium, friend of the animals because he was one of them, an anomality, a mineral, a landscape all by himself, he passed through this half a century too quickly to be noticed and too slowly for people to realize he was moving at all. Too intense to be loved.

His films are but his own. Unless you see them (we are waiting impatiently to see an important retrospective at the filmmuseum, real releases in one or two cinema’s, articles, dedications, traces) it is impossible to describe them or talk about them. Is he a Pasolini more Pasolinian than Pasolini, a Straub less dogmatic, a Murnau for the present time?

Stavros Tornes died last Tuesday, 26th of July, 9 o’clock at night. For the past year, he fought with the bureaucrates of the Greek Film Center in Athens for them to finally give him a budget of four million drachmas to make his film. He knew it would be his last. He knew he was going to die (cancer, refusal of hospitals etc.), he simply wanted to use his last energy for this Robinson Crusoe which will never see the light of day.

Four million drachmas is about 200.000 french francs, twenty lousy old million french francs, the average cost of his films. Greek “filmmakers”, the others, taking turns, receive fifty, sixty million drachmas, at least. It often takes them up to five years to make, with emphasis, “films” that cost twenty Stavros Tornes.

Stavros makes a masterpiece within a year while others spend half a decade piecing together their monuments of academism. Papatakis, alone, perhaps (he loves, admires tornes and tried to organize a homage) escapes this horde of drachma-eaters who killed the old Stavros a bit faster.

The very day of his death, a few hours before the end, the Center announced that it would finally grant the four million to Robinson Crusoe.

They didn’t know. Today, perhaps they are sorry. Time will tell.

In the images that Stavros Tornes left us, drunks play Rimbaud, grocers make love with the sand, blacks call out to the darkness.

It is a cinema before cinema, Homer operating the camera, Heraclitus recording the sound. A chiffonier cinema, Emmaüs whispers, incantations to Lumière: “Why have you left me alone, inventor of the devil?”

Stavros spoke like that, at every moment of his life, with the god Cinema. He was heretic, philosopher, poor amidst the poor. In Why do we film? he cites one of his texts from 1977: “The cinema is the place where you and I recognize each other, where “me” and others embrace each other.”

Love, nothing else.

Stavros has also spoken, lived, filmed with Charlotte van Gelder. Without her, nothing would exist. He is not dead as long as she is there to accompany the films they have made together.

And yet, somewhere in the world, an orphan is crying.