Start from zero

For a brief moment, the world was on fire. Impossible to say how and when the spark was lit, but we know the air had been thick with tense anticipation for quite some time, and it wasn’t long before the flames were crackling all over. What was felt during the ‘long 1968’ did not, as many still seem to imagine, erupt as a momentary and localized flash of lightning in a serene sky, but flared up at the convergence point of multiple smouldering hot spots and flaming areas, dispersed in space, evolving over time. The fires were spreading at a moment when struggles against Western colonialism and neo-colonialism gripped the entire ‘Third World’: at the same time the Vietnam war was increasingly polarizing the world stage, guerrilla groups such as Uruguay’s Tupamaros and Chile’s Movimiento de Izquierda Revolucionaria (MIR) were sprouting throughout Latin America, independence movements were gaining ground in Portugal’s African empire, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) had brought together various forces struggling against Israeli colonialism, and left-wing rebellion was proliferating in various Asian countries, from India and Nepal to Malaysia and the Philippines. Che Guevara’s 1967 call to ‘create two, three, many Vietnams’ was taken to heart by resistance movements all over the world, while propositions to construct new societal forms in Cuba and China seemed to offer fresh, grassroots-based models of socialism.

Meanwhile, in France and Italy, a wave of strikes and occupations took hold of factories and universities, coming to a head in the events of May 1968 and the hot autumn of 1969. In the US, the large-scale civil rights protests that had been gathering steam since the mid-1950s boiled over when the surge of demonstrations against institutional racism and the Vietnam War led to violent uprisings, escalating in the 1968 Chicago riots. The clashes with police and army troops painfully resonated with another event that had happened just a few days earlier, when Russian tanks brought winter to the Prague Spring, brutally crushing the dream of a ‘socialism with a human face’. From Brazil to Japan, from Northern Ireland to South Africa: everywhere, the sky was filled with smoke and ashes. As if there were nothing to be seen but the light of the flames. But behind the haze, there was still a lurking sense of horizon, connecting local and specific struggles to a broader narrative, seemingly bound together by resistance against class oppression and imperialism, holding the promise of another world.

Where was cinema, this great art of light and shadow, in all this turmoil? As oppositional leftist politics seeped deeper into all areas of cultural life, filmmakers were increasingly confronted with questions such as: How to contribute to the struggle? How can cinema make itself useful? ‘For filmmakers of all leanings’, wrote French critic Serge Daney, ‘in this near-open battle, in their very craft of film-making, a single problem emerges: How can political statements be presented cinematically? How can they be made positive?’1 The radical cinema that flourished so brightly in those years, on the wings of the various, adventurous ‘new waves’ that had infused the cinematic landscape with a playful spirit of liberation and iconoclasm, was one that saw itself as part of a broader project of national and international socio-political transformation. Its ambition was no longer solely to free up the camera and rewrite the codes of representation, but to make itself into a powerful vehicle for this transformation, by all means necessary. As worldwide revolts gave more and more currency to the idea of revolution, filmmakers were compelled to revolutionize their own means of production, expression and exhibition. When Brazilian filmmaker Glauber Rocha was working on his fabulous ‘opera-mitrailleuse’, Terra em Transe (1967), he wrote:

When film-makers organize themselves to start from zero, to create a cinema with new types of plot lines, of performance of rhythm, and with a different poetry, they throw themselves into the dangerous, revolutionary adventure of learning while you produce, of playing theory and practice side by side, of reformulating every theory through every practice, of conducting themselves according to the apt dictum coined by Nelson Pereira Dos Santos from some Portuguese poet: ‘I don’t know where I’m going, but I know I’m not going over there.’ 2

To start from zero, recharging with every film: for Rocha and many other filmmakers in Latin America and elsewhere, it was not merely enough to dress up political subjects and messages in traditional outfits, as so many colleagues inclined to do at the time. It was hardly enough to proudly raise the red flag and use revolutionary theory as a signpost of good will and sentiment, as Sergio Leone did in Giù la testa, opening with Mao’s statement: ‘The Revolution is not a dinner party… ’. No, these ideas had to be thoroughly explored and followed through within cinema, which meant that the fundamental aesthetic, economic and ideological conditions and conventions of cinema had to be rethought anew. What could a cinema be if it were free from the overpowering influence of what Jean-Luc Godard referred to as the devious pair of Hollywood/Mosfilm? How could cinema be liberated from the clutches of what Guy Debord and his Situationist posse, in 1967, called the immense accumulation of ‘spectacles’, keeping the spectator at bay in a state of passive contemplation, separated from life itself?

This challenge was not entirely new. Debates on cinema as a possible form of political intervention had been raging ever since the rise of Soviet Cinema in the aftermath of the Bolshevik Revolution – when Lenin commented that cinema was ‘the most important art form’ – and had resurged at various times, not in the least at the pinnacle of the Internationalist Popular Front alliance, when filmmakers such as Jean Renoir and Joris Ivens were swept up in their enthusiasm for communist ideals and the fight against fascism, and after World War II, in the context of the reconstruction of Italy and the revolution in Cuba. The heavy political stakes that were manifest in the 1960s put some of the debates that had been simmering within Marxist thought for decades back on the agenda, leading to radical, if often erratic re-readings of the work of Sergei Eisenstein, Dziga Vertov, Bertold Brecht and Walter Benjamin. Only now it was done in the light of the neo-Marxist and libertarian thinking that marked the time, from the pamphlets of Mao Zedong and Che Guevara, the anti-colonialist writings of Frantz Fanon and Aimé Césaire to the structuralist work of Roland Barthes and Louis Althusser. Once again, the fundamental tensions between art and world, appearance and reality, practice and theory, were subject to intense inquiry, centered around the idea of ‘militant cinema’.

Amongst the people

But the notion of militant cinema, always ‘at the service of the people’, actually indicated a divided landscape. ‘There are two kinds of militant films’, argued Jean-Luc Godard in 1970, ‘those we call ‘blackboard films’ and those known as Internationale films. The latter are the equivalent of chanting L’internationale during a demonstration, while the others prove certain theories that allow one to apply to reality what he has seen on screen.’3 This division essentially redoubled a debate that had already been initiated in 1920’s Soviet Union, between those who considered the primary concern of revolutionary art as being the search for new formal and theoretical models and those who saw it as first and foremost a question of effective communication in a form and language that was already understood by the ‘common’ people. In the 1960s, the latter tendency was exemplified by the proliferation of a ‘popular’ model of militant cinema, according to which the camera had to place itself in the heart of the struggle, where the filmmaker’s task consisted of capturing the shimmering traces of life as vividly and ‘authentically’ as possible, plucking the living reality like the flowers that Mao encouraged to bloom. In a way, this notion of militant cinema was already apparent in the work of internationalist ciné-travellers such as René Vautier and Yann Le Masson: cameras were taken to the battlefields and the barricades, to occupied universities and factories on strike, not only to testify to the events, but also to give voice to those who had remained voiceless for so long.

This task was taken up by militants and filmmakers worldwide. In Japan, the students of Zengakuren, with the help of documentarists such as Shinsuke Ogawa, started to use cameras to document their battles with the authorities; In Italy, Cesare Zavattini, one of the proponents of the Neorealist movement, successfully promulgated the idea of Cinegiornale liberi; in the US, the October 1967 Pentagon riot led to the establishment of a broad network of “Newsreel” collectives; in the Middle East, the Palestine Film Unit (PFU) dedicated itself to recording the Arab-Israeli conflict, under the motto, ‘gun in one hand, camera in the other’; and during the May events in France, hundreds of film technicians and filmmakers joined forces in the États Généraux du Cinéma and started to produce ‘Ciné-tracts’. This series of anonymous shorts (some made with the help of established filmmakers) was instigated by Chris Marker, who had previously also set up SLON (La Societé de Lancement des Oeuvres Nouvelles). It was under the auspices of this collective that Marker put together Far from Vietnam (1967), a portmanteau film made as a protest against the American military intervention in Vietnam, including contributions by Godard, Alain Resnais, Claude Lelouch, Joris Ivens, Agnès Varda and William Klein. ‘How to make a “useful” film?’, asked Klein, ‘Fiction, agit-prop, documentary, what? We were never able to decide, but we had to do something.’ At the time, Far from Vietnam came about not only as a vibrant expression of the solidarity that many tiermondistes in Western Europe and the US felt for the national liberation struggles that were raging all over the world, but it also opened up the question of ‘usefulness’, a concern that has always been central to the debates on art and politics: how does one close the gaps between ‘here’ and ‘there’, between those who take images, those whose images are taken and those who watch them? How does one translate the struggle without re-inscribing the relations of domination between those who have the power to represent and those who are merely represented? And in doing so, how does one create art that can reach the broad masses, not only adopting, but also enriching their own forms of expression?

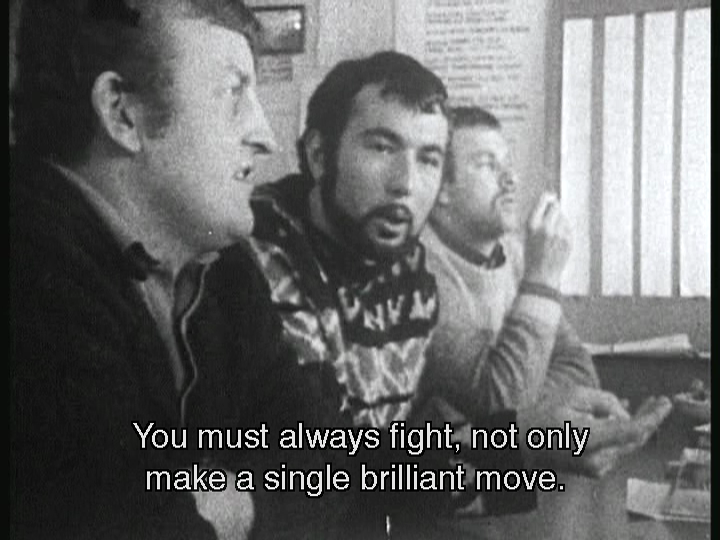

In his contribution to the collective film (a segment with the Vertov-inspired title ‘Camera-eye’), Godard explicitly took up these questions. ‘I am cut off from the working class, but my struggle against Hollywood is related. Yet workers don’t come to see my films.’ Perhaps engaging in the worldwide resistance against imperialism and colonialism, and creating a Vietnam in each of us, suggested Godard, can make us aware of what is common to both the filmmaker’s and the worker’s struggle. ‘What can bind us, the workers of Rhodiacéta and me, is Vietnam.’ Godard had actually visited the Rhodiacéta factory in Besançon just after March 1967, when the first occupations in France since 1936 had taken place, and would later also be there for the premiere of Far From Vietnam. On those occasions, he was always in the company of Chris Marker, who, during the production of the film, had been invited by the organizers of the local cultural programme to come and take a look. To Marker, who had previously been working in China, Cuba, Israel, and Siberia, they made a plea to give some attention to local matters: ‘If you aren’t in China or elsewhere, come to Rhodia. Important things are happening.’ After a first visit, Marker decided to make a film about the strike and secretly started shooting footage in the factory, interviewing workers, trying to involve them directly in the production of the film. The initial result of this effort was À bientôt j’espère, created by Marker, filmmaker Mario Marret and the SLON team. The film not only provides an account of the strikers’ concerns about working conditions, but also shows how they attempted to escape from their imposed identity, by laying claim to experiences deemed inaccessible and inappropriate to them: culture, education, communication. However, when the film was first shown to the strikers, they expressed a certain dissatisfaction toward it, finding it altogether too bleak, because it lacked perspective, and too romantic because it showed militants and strikes, while skipping over the preparation for the strikes and the training of the militants, which were considered the most important aspects of militant activism in factories. One of the workers, Pol Cèbe, told Marker:

Maybe you believe that audiovisual language, like written language, requires years of study, but we are convinced that this is not the case… We have so many things to say and we have a new way to say it, a new medium, a new weapon. 4

Responding to the criticism, Marker replied that the cinematic representation and expression of the working class should indeed be taken up by the workers themselves, from the inside of the struggle, not by well-meaning explorers coming from the outside. The only way to represent ‘the people’ without relying on the hallowed forms and customs that keep them in their place, so it seemed, was to provide them with their own means of representation. This would be the starting point for a longstanding collaborative effort between filmmakers and workers dedicated to fostering a cinéma ouvrier. They named themselves the Medvedkin Group, after the Soviet director Alexander Medvedkin, who in 1932 had travelled around the Soviet Union in a specially equipped ‘ciné-train’. Starting with Classe de lutte (1968), the collective initiated a model of filmmaking that aimed to annul the division between expert and amateur, producer and consumer, a model that would last in Besançon for almost five years before spreading to other places in France and beyond. The aim was no longer to simply produce militant films about the workers’ conditions, but a militant workers’ film, expressing, as Marker commented, a ‘change of consciousness’, incited by a desire ‘to learn how to see’.

Learning to see

For others, however, the challenge was not to make films about the process of ‘learning how to see’, but to make this process itself inherent to the production and reception of films. ‘It is not enough to do what Chris Marker did at Rhodiaceta – what The New York Times and Le Monde call “information”. We must rise above sensible knowledge and fight to make it rational knowledge… It implies a concrete analysis of a concrete situation.’ This quote, ripe with Marxist axioms, is taken from Pravda (1970), one of the films that Godard made with Jean-Pierre Gorin as the Dziga Vertov Group, undoubtedly the best-known proponent of the so-called ‘blackboard films’. For these filmmakers, it did not suffice to ‘start from zero’ and explore new sensible forms for new content: it was necessary to ‘return to zero’,5 to go back to the blackboard and start learning all over again, to rediscover the meaning of the ‘simplest’ acts of existence: seeing, listening, speaking, reading. This radical-regressive tendency took flight in France, where filmmakers and critics were looking for new tools of inspiration in the theoretical raids that had been traversing the discursive landscape since the beginning of the decade, particularly in the guise of Althusserianism, which in its desire to re-found Marxism, brought together fairly heterogeneous theories – drawn from psychoanalysis and semiology – under the concept of Structuralism. The most elaborate application of the structural thinking in the field of cinema emerged on the pages of such magazines as Cinéthique and Cahiers du Cinéma which, triggered by the work of the Tel Quel group, started to cultivate a lively debate on problems of ideological criticism and a potentially revolutionary ‘theoretical practice’ in cinema. After 1968, critical thinking in film increasingly found itself in the throes of a mode of reading associated with what Louis Althusser called ‘symptomatic’: a reading that searches for meaning under the surface of things, lifting the veil of images to reveal the constitutive presuppositions that make them possible in the first place, the underlying logic that determines what can and cannot be seen and thought within its framework.

The key word in this period was ‘ideology’, which was considered not simply a lie made up to fool the ignorant, or the inverted reflection of real social relations (as in Marx’s Camera Obscura model), but as a system of representation with its own logic and materiality: a set of images, myths, ideas and concepts that defined how the world was supposed to be experienced or negotiated. The reality put forward through ideology is not the system of the real relations that govern how we live, but our imaginary relationship to the real relations in which we live. What is generally taken for visible self-evidence should in fact be read as a form of encoding, whereby a society or authority legitimates itself by naturalizing itself, by rooting itself in the obviousness of the visible. According to this logic, all films had to be considered ‘political’, because they were always already overdetermined as expressions of the prevailing ideology, merely reproducing the world as it is experienced when filtered through this ideology. In view of a reality which was considered already coded, the challenge for any filmmaker was to break with reproduction or naturalization of reality, to uncover the unconscious mise-en-scène that precedes any cinematic mise-en-scène. As Serge Daney wrote, ‘Realism must always be overcome.’ Truth was put on the side of the signifier, while the signified was put on the side of ideology, or in Lacanian terms, on the side of the imaginary. Everything that involved a direct relationship between the sign and a referential reality, image and appearance, was suspected of being ideological, conforming to the self-evidence of the given. The only possible counter-strategy consisted in creating an awareness of the gaps between referent and sign, between what the image represents and how it represents it. It was this idea of disjunction, this breaking up and questioning the apparent unity of cinema by way of a ‘radical separation of elements’ (Brecht), that was at the heart of Godard’s aim to ‘produce films politically’. Political struggles should not merely be made into an object: film itself should be made into an object of struggle and criticism.

Godard did not simply want to create or represent an alternative worldview, but to investigate and deconstruct the whole process of signification out of which worldviews are constructed. Starting with La Chinoise (1967), the Althusserian pedagogy of ‘seeing, listening, speaking, reading’ became the basic rule in his play- book, the fundament of his so-called ‘blackboard films’. La Chinoise is a depiction of the ‘children of Marx and Coca-Cola’ who placed cultural concerns at the centre of their revolt in an attempt to rescue everyday life from the clutches of the ‘hidden persuaders’ which had colonized it. But Marxism not only functions as the subject of representation, it is also the principle of representation. While the Marxism represented here is Chinese Maoism as it figured in the Western imagination at the time – symbolized by the two Red books, Mao’s Little Red Book and the student-run Cahiers Marxistes-Leninistes – the film’s mise-en-scene is constructed according to the basic ideas underlying Althusserianism.6 The rhetoric and stereotypes of Maoism and Marxism are here merely used as a catalogue of images and a repertoire of phrases from which Godard, as always, had sampled various quotes, symbols and objects, setting them up as part of an extensive classroom exercise. Indeed, this is a film in the making, about learning how to see, listen, speak and read the leftist discourses that were pervading Parisian cultural life, at a time when the Cultural Revolution in China served as a projection screen for the hopes and dreams of the radical left, as an exit route to escape the straightjacket of orthodox Marxism. It is also a lesson on how to see and listen with them, as if they were but a set of illustrations and formulas written on a big blackboard. The scenographic setting becomes a classroom, the dialogue a recitation, the voice-over a lecture, the shooting an object lesson, the film-maker a schoolmaster: always the logic of school.

This pedagogic principle is the basis for Godard’s ‘militant’ films: only the application of a Marxist analysis of image and sound was able to bring light to all those roaming in the dark. And there could be no semiology without semioclasm: the unified appearance of the audiovisual had to be broken up, the correspondences between sounds, words and images undone, so that they could speak for and against themselves. In Godard’s films, there is hardly any attempt to point out the origins of the sampled elements. There is not even an attempt to question discourses by others, such as Althusser’s ‘Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses’ in Lotte in Italia (1971), or Brecht’s lesson on the role of intellectuals in the revolution in Tout va bien (1972). It is merely a matter of looking for other elements to put them to the test, rearranging their connections and reframing their meaning. The urgency of learning anew in order to put a halt to the endless circulation of images, to look underneath the surface of images, to read between the lines: this was the inclination that was feverishly developing among the French cinephiles of that time – the post-nouvelle vague moment of structuralism and the golden age of semiology. Political commitment in cinema once again appeared as commitment to form, rather than to revolutionary content. Against the old assumption that there is no ‘responsibility of forms’, there could no longer be a representation of politics without critically reflecting on the politics of representation.

Beyond the surface

In reference to Marx and Engels’ Communist Manifesto, Godard would say, ‘The dominant class creates a world after its own image, but it also creates an image of its world, which it calls a “reflection of reality”.’7 With the idea that the reflection of reality should be considered an ideological construction, a longstanding debate was once again brought to the fore: the debate on realism. For those who were trying to develop a film critical thinking in a Marxist framework, André Bazin’s longstanding legacy of ‘ontological realism’ was no longer of any use. Everything that constituted that paradigm – the notions of continuity and transparency, the epiphany of the ‘sensible real’ – had to be violently renounced. As Godard had already indicated in the scenario of Les Carabiniers (1963), it is not enough to say how things are real: one has to say how things really are. It was this adage, adapted from Bertold Brecht, that was at the heart of the impulse to decipher the world, the desire to look behind the appearance of things. It was Brecht who, back in the 1930’s, had stated:

Less than ever does the mere reflection of reality reveal anything about reality. A photograph of the Krupp works or the A.E.G. tells us next to nothing about these institutions. Actual reality has slipped into the functional. The reification of human relations – the factory, say – means that they are no longer explicit. So something must in fact be built up, something artificial, posed.8

Brecht’s ideas on realism as the exposure of a society’s causal network and dominant order had already been used as a reference in the film criticism of the 1940s and ’50s, even – mediated by the work of Joseph Losey – in the Cahiers du Cinéma. Throughout the first half of the 1960s, however, another interpretation of Brecht’s ideas would hold sway, one less concerned with film as an art of perception than film as a system of signification. The main inspiration from this turn came from Althusser and Roland Barthes, who treated Brecht’s views as a counterpoint for the primacy of psychology and identification in art, which was considered part and parcel of the bourgeois worldview. It had never been Brecht’s intention to condemn the lies displayed by art, but rather to call attention to the ways in which art can demonstrate to spectators the workings of a society that lies beyond them, and invite them to take part in its transformation. What is stigmatized is the illusion, which tends to present reality as a natural and unproblematic given and which keeps the spectators in a state of passivity, ‘hanging up their brains with their hats in the cloakroom’. An active spectator should refuse identification and remain at a distance, to be able to assess the causes and remedies for the injustices suffered. The mirror of transparent myths in which a society can recognise itself first has to be broken, before it can really learn to know and change itself. In Mythologies (1957), Barthes uses Brecht’s critique of mystification and identification to point out the shortcomings in Eli Kazan’s On the Waterfront, especially in its final scenes when, after having exposed the violence and the corruption of the workers’ union, Marlon Brando’s character decides to go back to work and give himself over to the exploitative system. Barthes wrote:

If there ever was one, here is a case where we should apply the method of demystification that Brecht proposes and examine the consequences of our identification with the film’s leading character… It is the participatory nature of this scene which objectively makes it an episode of mystification… Now it is precisely against the danger of such mechanisms that Brecht proposed his method of alienation. Brecht would have asked Brando to show his naïveté, to make us understand that, despite the sympathy we may have for his misfortunes, it is even more important to perceive their causes and their remedies.9

Similarly, in Brecht’s famous Mother Courage, what is shown in the play is not so much the suffering of a mother figure, but the result of a failure to come to grips with her historical situation. As spectators, we participate in her blindness at the same time as we are made aware of it. As Barthes once observed (in reference to Charlie Chaplin’s films), to see someone else not seeing is the best way to intensely see what he or she does not see. Staging events in such a way that what had seemed natural and immutable is revealed as historical and thus changeable: this is what Brecht called the Verfremdungseffekt. As a derivative of the Marxist theory of alienation, the formalist notion of oestranenie and the surrealist practice of errance, this strategy consists of ‘turning the object of which one is made aware, to which one’s attention is to be drawn, from something ordinary, familiar and immediately accessible into something peculiar, striking and unexpected’. In essence, it is an effect of displacement, the establishment of a gap between what is on show and how it is experienced and interpreted – or in semiotic terms, between signified and signifier – in order to demystify its apparent inevitability and appropriateness and draw attention to its own artifice, rather than attempting to conceal it. It is an idea that runs through Godard’s films of the 1960s and early ’70s, as well as films by Harun Farocki (Inextinguishable Fire, 1969), Nagisa Oshima (Death By Hanging, 1968) and Jean-Marie Straub & Danièle Huillet, to name a few.

The work of Straub & Huillet is particularly affiliated with Barthes’s interpretation of the verfremdungseffect, according to which actors should speak their lines as verse instead of attempting to make formal and ordered language appear as the natural expression of psychological states. Barthes cites with approval Brecht’s idea that the actor should speak his or her part not as if he were living or improvising it, but ‘like a quotation’. It is this principle of embodied storytelling, of ‘acting out’, that Straub & Huillet have always applied to their films. The title of their first film, Nicht versöhnt (1965), can be read as a Brechtian axiom par excellence: existing divisions and contradictions are not to be reconciled – on the contrary, they should be exposed and accentuated. Inspired by Brecht, Barthes wrote that ‘class division has its inevitable counterpart in a division of meanings, and class struggle has its equally inevitable counterpart in a division of a war of meanings: as long as there is class struggle (national or international), the division of the axiomatic field will be inexpiable.’ 10 This war of meanings is what was at stake in the pedagogical space of the ‘blackboard’ cinema of the 1968 generation. As discourse is always a space of conflict and a form of violence, it has to be unveiled and disclosed as dialectical contradiction, acted out in the form of sheer non-reconciliation – for in contradiction lies hope. For Straub & Huillet, dialectics meant ‘dividing one into two’, rather than ‘combining two into one’. This is apparent in the mise-en–scène, in which there is always a collision between what is seen and what is heard, between past and present (what Straub called a ‘science-fiction effect’), between words taken from existing literary texts, how those words resonate and those who say them. In Othon (1969), for example, Pierre Corneille’s eponymous text is recited on Mount Palatine, among the ruins of ancient Rome, in full view of the contemporary cityscape of the Italian capital, by a predominantly Italian cast, dressed in traditional togas. In this way, the film sets up a system of gaps and displacements, transgressing numerous historical, geographical and linguistic boundaries in order to unfold a genealogical trajectory of European power structures, from the modern city of Rome, to France in the era of the Grand Siècle, to the ancient Roman Empire. To the 1968 generation, the Straubs suggested that the question of power and class relations was a lot older than imagined. Didn’t the first sentence in the Communist Manifesto already state that ‘The history of mankind is the history of class struggle.’?

When Othon was released in France, it was heavily criticized in certain leftist circles as an abject film, not only because of the unusual setting and diction (‘the worst recitation in a school context’, wrote a critic), but mainly because of its incapacity to ‘adapt’ and enlighten a historical text for spectators in the present, instead translating it into an incomprehensible film in which no political message could be found. The response of the Cahiers critics was that films such as Othon, as well as Sotto il segno dello Scorpione by the Taviano brothers, Yoshishige Yoshida‘s Eros + Massacre, or Robert Kramer’s Ice – films that had been vigorously

defended on the pages of Cahiers – were to be considered political precisely because they were not satisfied with the pure and simple delivery of a straightforward political message. Rather, they ‘start at the beginning (which is also one of the conditions of political analysis) and carry out on their very materiality – that of the signifiers they put into play, as well as that of the conditions and means of production of these signifiers – a scriptural work which, as such, constitutes political work.’11 In other words, political cinema has to start from its own materiality, examine its own means and conditions of existence, and reveal rather than hide the work which has gone into its making, as well as its production of meaning. Only by refusing the effects of recognition and transparency, by criticizing the illusions of consciousness and unravelling its real material conditions and contradictions, can cinema activate the spectator, prompting him to start where the film ends, completing what it has left unfinished.

Politics of representation

Can a revolutionary film be made without criticizing the dominant forms of representation? This question, at the core of the many debates on militant cinema, became explicit in the discussion over two French films released in 1972: the Dziga Vertov Group’s Tout va Bien and Marin Karmitz’ Coup pour Coup. The similarity between the two films is striking. Both proposed an account of the class struggle which was stirring in France four years after 1968, complete with factory occupation and sequestration, but in contrast to the various ‘direct’ documentations of particular uprisings and strikes, the filmmakers chose fictional forms with which to depict the workers’ revolt. Additionally, the filmmakers, who shared similar political sympathies which leaned towards Marxist-Leninism, chose to produce and distribute the films through conventional channels rather than the various parallel circuits that had been set up in previous years. So the difference between the two films could not be found in the choice of subject or diffusion, but in their formal approach. What characterized Coup pour Coup was an adherence to what Althusserians referred to as a ‘spontaneous ideology’. Karmitz chose to ask real workers to ‘act’ out their actual life in a ‘natural’ way, and filmed them in a dispositive that put the spectator in the heat of the struggle, directly ‘amongst the people’. At last, commented advocates of the film, a voice was given to the people. For once, the working class was shown in their own environment, which is to say in the place of production, exploitation and repression. For once, by reflecting the concrete manifestations of the proletarian class, a film actually provided sensible knowledge of capitalist social relations. As an enthusiast wrote, ‘Confidence was given to the experience and the naturalness of the workers, and that paid off well: life is revealed in all its truth and intensity.’

According to the critics of the film, however, the idea that there was an actual ‘truth’ to capture and communicate through images and sounds completely ignored the fact that truth is not inherent in things, but alludes to a relationship of conformity between an object and its knowledge, between a reality and its reflection. As this relationship is always part of an ideological process, it does not suffice to produce sensible knowledge of capitalist social relations and proletarian class struggles. It is necessary to go beyond that and create rational knowledge of the internal laws of this process. These critics challenged the assumption that a redoubling of reality gives way to an active reflection of that reality: it is not because the reflection of reality on the screen is antagonistic to the dominant vision that they have revolutionary value. Making a film from the point of view of the working class should not be confounded with giving voice to the workers. It can never be an end in itself. To leave things at the level of appearances, of the sensible, only affirms the ‘cult of spontaneity’ and leaves the dominant ideology unchallenged. Furthermore, as Daney suggested, ‘naturalising’ also implies a denial and an effacement of the dialectics of exclusion that lie at the heart of the dominant order.

Naturalism is the game of readjustment where those such as young people, immigrants and peasants who were previously forbidden from making films and were never seen on the screen are now suddenly included in fiction films as though they had always been part of them. They are ‘naturalized’ in every sense of the word, recognized by the law, made normal, natural and legal, and accede to a sort of ‘iconic dignity’. but what is glossed over in this process … is how and why they break into the story.12

Naturalism – always the bête noire of the Cahiers at the time – is thus seen as a point of view and a way of filming that renders natural what is in fact not. According to the same critics, this tendency towards naturalism in Coup pour Coup is confirmed by Karmitz’ “typecasting” decision to give the roles of the other characters – the bosses and the union delegates – to professional actors, conforming to the idea of everyone in his or her place, in harmony with their ‘nature’, with ‘the way people are’. Class struggle is neither represented nor suppressed, it is simply taxonomlzed. Karmitz essentially reasserts a capitalist division of work, founded on a simplified analysis of class struggle based on relations of repression and resistance. As he himself explained, ‘The form of the film is conditioned by the contrast between repression and resistance. Everything is based on that.’ Godard and Gorin, on the other hand, opposed this mise-en-scene of workers playing their ‘natural’ roles by working with professional actors:

The militants who distrust actors ask workers to play their proper role. Traditional cinema takes big stars and makes them play the roles of proletarians. We think that, in the present situation, a worker who plays like Jean Gabin cannot embody his condition but only recount himself. So we have taken actors to play the roles of workers, but downtrodden and exploited actors, who feel the class struggle in their stomach. That has permitted us, by putting them in a correct situation, to really oppose them to the actors representing the chieftains. 13

This choice was rooted in a desire to highlight the contradictions between the status of actors and the social roles that fiction traditionally assigns to them. Casting the well-known French actor Yves Montand, for example, was not based on his natural tendency towards ‘repression’, but because of the dominant idea that actors should stick to their characters. It is precisely because Montand is perfectly able to embody a worker with a flair for spontaneity that they did not ask him to do so. For Godard and Gorin, one cannot transform actors into workers and workers into actors without asking what has to be transformed. Before representing classes, one has to reflect on the ideological conception of that representation, because there is already a dominant idea on how to depict class models, in their way of being, moving and talking. Exploring the theme of class struggle to destroy this idea does not hold up. Rather, the struggle itself has to traverse the work on the film; it has to be extended through cinema.

The point of Tout va bien, whose mise-en-scene is clearly inspired by Brecht’s lehrstücke (an attentive critic called the film ‘the Sesame Street of political radicalism’), is to take up the contradictions that are left unspoken in Coup pour Coup – between the practice of cinema and the practice of politics, between the status of workers and the status of actors – in order to make them ‘productive’. This is also why Karmitz was criticized for not using the recordings of the discussions between members of the film crew and the actors before and during the shooting: instead of developing an active reflection of the working process, he chose to give the film a sense of authenticity, covering up what is at stake in the contradiction between politics and cinema. Both Tout va Bien and Coup pour Coup essentially started from the same assumption: that one has to know the world, reveal the reality under the surface of things, in order to be able to transform it. While the first chose to create a reflection of reality, the second chose to expose the reality of reflection. While the first chose to revive a specific struggle and reproduce a sensible perception under the watchful eye of the camera, the second chose to put to work a rational reflection on the internal laws of the struggle. Why else has Marxist thought broken with the notion of contemplation? A film too, it was said, should intervene.

Behind the firing lines

In Vent d’Est, another film by the Dziga Vertov Group, there is a sequence in which Glauber Rocha stands at a dusty crossroads, with arms outstretched. A young woman with a movie camera goes up to him and says, ‘Excuse me for interrupting your class struggle, but could you please show me the way towards political cinema?’ Rocha points in front of him, then behind and to his left and says, ‘That way is the cinema of aesthetic adventure and philosophical inquiry, while this way is Third World cinema – a dangerous cinema, divine and marvelous, where the questions are practical ones…’ Rocha puts forward what was felt to be the main difference between the European ‘counter-cinema’ and the so-called Third World cinema – which is in itself anything but a stable phenomenon. While, for European filmmakers, it seemed in the first place to be a matter of radically opposing, or even, as Godard mentioned to Rocha, ‘destroying’ the industrially and ideologically dominant cinema, for many filmmakers in the Third World, it was not a matter of destruction, but of invention, as a way to escape the stranglehold of (neo)colonization, repression, censorship and underdevelopment. Although Rocha, one of the pioneering filmmakers of the Brazilian Cinema Novo movement, always expressed a strong admiration for Godard, he was also aware of the deep gap between them:

Godard sums up all the questions of today’s European intellectuals: is making art worthwhile? The question is an old one… And that is what is so annoying in Europe today: the issue of the usefulness of art is old, but it is in fashion, and, in cinema, it is up to Godard alone to come to grips with the crisis. Godard is what Solanas is to us in Buenos Aires. The truth, however, whether our intellectual fellow-countrymen want to hear it or not, is that European and American cinema has gone up a road without hope, and it is only in the Third World countries that there is a way left to make cinema.14

For Godard, Rocha laconically notes, cinema was over and done with. For filmmakers in the Third World, it was just beginning: ‘Godard & Co. are above zero. We are below zero.’ Some of the most prolific explorers of these new beginnings could undoubtedly be found in Latin America, where filmmakers offered arguments for a cine de liberacion, for cine imperfecto, for an ‘aesthetic of hunger’, a ‘third’ or ‘triccontinental’ cinema of decolonization – all terms that have since framed many debates on political cinema and have become part of the rhetoric of resistance against imperialist oppression, and for the empowerment of the people in the Third World. All these filmmakers were grappling with the rise of nationalism and militancy in the aftermath of several political and social incidents that had erupted throughout the continent, from the unfinished workers’ revolution in Bolivia in 1952 to the military overthrow of Argentina’s President Perón in 1955, and, most significantly, the guerrilla war in Cuba, which led to the establishment of a socialist regime in 1959. It was not only the Cinema novo filmmakers, but also Jorge Sanjinés and the Ukamau group in Bolivia, Julio García Espinosa and Tomás Gutierrez Alea in Cuba, Miguel Littín, Raúl Ruíz and Patricio Guzmán in Chile, and Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino in Argentina: they all expressed the need for thinking about cinema as a social instrument, as a weapon in the struggle for national liberation and cultural transformation – ‘with an idea in one´s head and a camera in one´s hand’.

‘We must discuss, we must invent…’ It was this quote by Frantz Fanon that opened the manifesto ‘Toward a Third Cinema’ (1969), written by Solanas and Getino, who in the same year also released La Hora de los Hornos (Hour of the Furnaces), a didactic film fresco produced clandestinely under the Péron regime and signed by the Cine Liberación Group. In the manifesto, arguably the most influential articulation of Third World cinema, Solanas and Getino follow Fanon’s lead and argue that cinema should be ‘placed first at the service of life itself, ahead of art; dissolve aesthetics in the life of society’. Its objective was nothing short of a ‘decolonization of the mind’. In line with the thinking of the Russian avant-gardes of the 1920s, and Eisenstein in particular, according to whom films had to ‘plough the mind of the viewer’, cinema not only had to contribute to the development of a new radical consciousness, but should also be instrumental in the revolutionary transformation of society, as a means to an end. According to Rocha, however, revolutionary cinema should be seen as more than a simple instrument that could supposedly push spectators into the path of political consciousness and action:

The artist must demand a precise identification of what revolutionary art at the service of political activism actually is, of what revolutionary art thrown into the spaces opened up to new discussions is, and of what revolutionary art by the left and operated by the right is. As an example of the first case, I, as a man of film, cite La hora de los hornos, a film by the Argentine Fernando Solanas. It is typical of the pamphlets of information, agitation and controversy that are currently being used by political activists around the world. 15

To illustrate the second case, Rocha suggested his own films, which are not composed as theoretical guides for action, but rather as attempts to break with what he saw as bourgeois rationalism and the colonial logics of representation, induced as they were by exotic primitivism and social miserabilism. Rocha claimed that the work of Godard and Solanas, which basically consists of opposing an oppressive logic with a revolutionary one, does not allow for a way out of the deadlocks imposed by imperialism and capitalism. For him, revolution could only be accomplished as a form of anti-reason and irrationalism: ‘Revolutionary art must be magic, capable of bewitching man to such a degree that he can no longer stand to live in this absurd reality.’ The hopelessness of reality could only be overcome through enchantment; freedom could only be devised through popular mysticism (in favor of ideological demystification), something he saw arising from the historical relationship between religion, folklore and rebellion. This interest in breaking the course of history and advocating some kind of return to the past – not unlike Walter Benjamin’s ‘tiger’s leap into the past’ – was not only something that Rocha shared with the Straubs (Rocha organized screenings of Othon in Brazil, while Straub spoke highly of Rocha’s Antonio das Mortes, from 1969), but even more so with Pier Paolo Pasolini, whose work is also characterized by a certain regression towards religious themes and irrational impulses. There has always been a fraternal, yet heated dialogue between the two filmmakers. Rocha criticized Pasolini’s depiction of the Third World, which he saw as merely an alibi for perversion. Pasolini accused Rocha of having succumbed, as had Godard & Straub, to the blackmail of a certain leftist thinking which prescribed a radical subversion of representation and a conscious frustration of the spectator’s expectations.

What is it that Godard, the Straubs and Rocha are supposed to have in common? According to Pasolini, through their boundless provocation and transgression of cinematic codes, their ‘unpopular’ films at the same time render themselves as agent provocateurs, martyrs and victims: the search for freedom from repression had led to a suicidal intoxication and didactic self-exclusion, veering violently towards the negation of cinema. For Pasolini, who was a great admirer of Christian Metz’ semiology of cinema, there was no doubt that an infraction of the codes is a necessary condition for invention – after all, the first step towards liberation is to let go of certainties and open up to the unknown. But it also implies a refraction of self-preservation, one that opens the way to self-destruction. When the codes are too violently violated, when the front lines of transgression and invention are crossed too far behind the firing line, there comes a point when the codes can be recuperated for endless possibilities of modification and expansion, and any notion of struggle ends up being neutralized. This is when the struggle is no longer fought on the barricades, but on the other side, behind vacated enemy lines, at which point the enemy has disappeared, because he is fighting elsewhere. ‘What is important,’ wrote Pasolini, ‘is not the moment of the realization of invention, but the moment of invention. Permanent invention, continual struggle.’16

The end of a beginning

Where lines crossed? Isn’t that what happened when the ‘new waves’ of the 1960’s, in their insatiable thirst for freedom, got caught up in the well-intended games of decoding and deconstruction, when the liberties attained led to an endless search for signification, to a point where there was no more sense to give? The new waves had established an adventurous cinematic space of transversals and transgressions, where codes were cut loose from their moorings, images and sounds were set free from their bondage, where drifting took the place of wondering and iconoclasm replaced scandal. Still, it was only a matter of time before the freedom of representation would become a suspension of representation altogether, when the screen was turned into a blackboard, and the art of showing became an act of endlessly revealing. Godard’s work is undoubtedly the best example of this evolution: from the playful liberations of his first films to the Althusserian experiments of La Chinoise and the critical didacticism of the Dziga Vertov Group. In the end, critical cinema was turned on itself, taking “refuge in its own negation. hoping to survive through its death” (Adorno). This impasse is what is at stake in Ici et Ailleurs. The story is well known: in 1970, a year after Yasser Arafat was elected leader of the PLO, the Palestinian Liberation Organization, Godard and Gorin were invited to make a film in support of the Palestinian struggle. They were not the only ones. Around the same time, other collectives and filmmakers, including Pacific Newsreel, Groupe Cinéma Vincennes, Francis Reusser, Jean-Pierre Olivier de Sardan (delegate of the French Maoist party), and Masao Adachi & Kôji Wakamatsu (associated with the Japanese Red Army) also travelled to Palestinian camps in Lebanon, Jordan and the West Bank to record the realities of the struggle. Just a year earlier, the Palestine Cinema Unit, founded under the aegis of three pioneers, Hany Jawhariyya, Sulafa Jadallah and Mustapha Abu Ali, had made the first militant films against Israeli colonization.

The aim of Godard and Gorin’s film, initially entitled Jusqu’à la victoire (Until Victory), was to ‘understand the thought and working methods of the Palestinian revolution’. Before travelling to Palestine, they had put together a storyboard that systematically conceived the path towards revolution: the people’s will + the armed struggle = people’s war + political work = the education of the people + people’s logic = the protracted war, until victory. But just a few weeks after the filming, which took place between March and August 1970, Black September happened: Jordan’s King Hussein decided to wage war on the PLO, resulting in the massacre of thousands of Palestinians. Confronted with the death of many of the film’s collaborators and growing antagonism within the Arab population, Godard was forced to rethink the concept of the project, a challenge that became even more daunting in light of the events that took place during the 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich. It took him over five years to find a configuration for the images and sounds they had gathered, five years to come up with a response to the question of how to make sense of the gaps between intention and reality, commitment and failure, then and now, here and there.

Godard, together with Anne-Marie Miéville, did what he had always done: take the question and put it at the heart of the film. The film turned into a moving mournful reflection on the impossibility of a filmmaker to intervene in political struggles, and the difficulty of escaping the endless chains of images and sounds in which we are all caught up. Godard bemoaned how self-proclaimed militant films, despite good intentions, tend to ‘put the sound too loud’, always covering up the sound of one voice with that of another, obscuring what really is there to see in the images. As part of a vigorous auto-critique, the film exposes the cinematic trickeries by which we just love to be fooled: how images always deceive us, how sounds always hide something else, how we are to learn to read the signs. The desire to put a halt to the circulation of sounds and images ends up being a lamentation for the end of a certain belief in the power of cinema, accompanying the end of a belief in any change whatsoever. The act of mourning the failure of the Palestinian revolution becomes an allegory for the failure of all revolutions.

The end of the leftist era is also depicted in another film that came out around the same time: John Douglas & Robert Kramer’s Milestones. The film portrays the demise of the oppositional movements from the inside, something which both filmmakers, as former members of the Newsreel collective, had experienced first hand. At the end of the 1960s, both had worked on various films denouncing American imperialism, including People’s War, which aimed to give a view on the Vietnam war from the perspective of partisans in North Vietnam. Kramer had already made a trilogy of films – In the Country (1966), The Edge (1967) and Ice (1969) – which explored the limits of a collective desire for revolution and armed struggle. Milestones was an attempt to grasp what had happened to these militant desires once those limits had been reached, and they were redirected towards the exploration of new communal forms. As Kramer said:

A lot of people say that the ‘70s are like a time of falling away from political militancy. There is a sense in which that is true – if emphasis is put on the word militant and a strong, sustained confrontation with the powers that be. But there is another sense in which that is not true, because we came to a dead end, and it seemed as though we could not continue to be militant in that same way.17

Kramer & Douglas wanted to make ‘a film about rebirth’, providing a mirror for all those who had been involved in the struggles to look into and evaluate themselves, in order to go further. In a sense, it was not only the rebirth of certain militant ideas and energies that was at stake, but the rebirth of a certain cinema, a cinema of myth and dream, a cinema steeped in tradition and history. Is it any wonder that at the end of their ‘naive’ red period, the Cahiers du Cinéma celebrated the film as a ‘positive’ example of a new militant cinema? Tired of their own dogmatism and voluntarism, exhausted from the terror of the significant, the Cahiers once again turned to their roots, to Bazin and his concern for morality, to American cinema and its mavericks (a few months later Monte Hellman’s Two-lane Blacktop was heralded for its refutation of “the old cinema of acute difference and fatal necessity”18). As a sort of counterweight for Ici et Ailleurs, which problematizes any possible reflection on militant history by confronting all discourse with its own lies, Milestones attempted to make the militant left tell its own story, by returning to the foundations of classic American cinema: the travelogue, the Western, the communitarianism of John Ford and Anthony Mann. A strange ‘return of the repressed’. But hadn’t Passolini seen it coming all along: ‘Excessive transgression of the code can only lead to a nostalgia for it’?

The fire next time

‘The dream is over,’ a voice tells us at the end of Chris Marker’s Le fond de l’air est rouge (1977). When the smoke had cleared, all leftist resolve seemed to have withered away. In France, Chile, Portugal and elsewhere, revolutionary movements fizzled into rupture and defeat. In Italy and Germany, the hopes of the radical left collapsed in violence and despair. In China, the Cultural Revolution turned out to be a cruel failure, leading to famine and chaos. And so mourning began, mourning for failed hopes, mourning for possibilities that had turned in on themselves, mourning for a sense of togetherness that had somehow collapsed into contorted factionalism: a mourning without end. Soon enough, the energies of militant histories were overturned by some of those who had once fully embraced them. All that the ‘children of Marx and Coca-Cola’ and their actions had accomplished, so they argued, was to pave the way for a rekindled capitalism, allowing our societies to become free aggregations of unbound molecules, whirling in the void, deprived of any affiliation, completely at the mercy of the law of capital. All resistance was said to be futile, even suspect, in any case causing more harm than good. Revolt could hardly change the world; it could only give rise to cruelty and catastrophe. History was identified as an enormous, catastrophic ruin, perpetually piling wreckage upon wreckage. The memory of the Gulags dissolved all memories of revolution, just as the memory of the Shoah had replaced remembrance of antifascism. In claiming to have delivered us from the ‘fatal abstractions’ inspired by the radical ideologies of the past, Western capitalism and its political system of democratic parliamentarianism presented themselves as a universal shield, protecting us from all forms of terror and totalitarianism. ‘Capitalism won the battle, if not the war,’ the voice says, ‘but in a paradoxical logic, some of the staunchest opponents of Soviet totalitarianism, these men of the New Left fell into the same whirlwind.’

In 1977, the hijacking of Lufthansa Flight 181 set a gruesome series of events in motion, the Bologna uprising and the Egyptian Bread Riots collapsed violently, and Margaret Thatcher’s re-initiation of privatization announced the neoliberal turn. In 1977, the Sex Pistols gave voice to the ‘No Future’ generation, Jean-François Lyotard wrote the first draft of La Condition Postmoderne, and former Marxists Bernard-Henri Lévy and André Glucksmann declared the impossibility of all revolutions. In 1977, Chris Marker presented the first version of his requiem for the revolutionary era (Le fond de l’air est rouge), Robert Kramer documented the aftermath of what was possibly the last revolution in 20th-century Europe (Scenes from the Class Struggle in Portugal) and Robert Bresson made his portrait of the lost generation of post-May ’68 (Le Diable Probablement). According to Rainer Werner Fassbinder, this was a generation that rejected every form of commitment, ‘because commitment for the film’s young characters – whom Bresson seems to understand so well – is mainly an escape into an “occupation” which keeps that commitment alive, an escape from the awareness

that everything goes on regardless of you and your commitment.’19 A year later, Fassbinder would create his own vision of this ‘third generation’, coming after those who had dreamed of changing the world and those who had faded into violence, a generation ‘which simply acts without thinking, which has neither a policy nor an ideology, and which, certainly without realizing it, lets itself be manipulated by others, like a bunch of puppets’. After the collapse of utopian rebellion into desperate dystopia, all that seemed to be left was an overwhelming sense of bitterness and nihilism. Nothing but lost illusions, utopias gone wrong, ruins amidst the ruins. As if despair, as Godard mentioned in Numero deux, became ‘the ultimate form of criticism’.

At the same time that the leftist era crumbled under the weight of historical fatality, a certain utopia of cinema was believed to have come to an end. Serge Daney once claimed that Pasolini’s death in November 1975 – a few weeks before the release of Salò, which was his own personal cry of desperation – marked the point when cinema stopped playing the role of sorcerer’s apprentice and became a consensual landscape, instead of the space for division and confrontation that it used to be. The politicization of cinema – whether in content or in form – that had been associated with the upheavals and the hopes of the 1960s and ’70s, gave way to a general feeling of disillusionment and powerlessness. Just as the failure of the October Revolution had accompanied the end of the utopia of cinema as a mystical marriage between art and science, poetics and community, the implosion of leftist dreams accompanied the dissolution of the idea of cinema as a realm of discord or a weapon in the struggle. What had once been called ‘militant’ or ‘political’ film had disappeared in the shadows of a bygone time that was best left to forgetfulness. In 1977, Daney explained why Cahiers du Cinéma, after having abandoned the ideological critique of the ‘non-legendary years’, too lost interest in the familiar models of militant cinema:

It is because it failed to furnish this imaginary encounter with the people, because there were nothing but sectarian films, made hastily by people who didn’t care about cinema… Today I think that militant films have the same defect as militant groups – they have the Mania of the All: each film is total, all-inclusive. A true militant cinema would be a cinema which militated as cinema, where one film would make you want to see a hundred others on the same subject. 20

After the deluge, with the disappearance of the material reality of the struggles and the horizons that gave them meaning, the existing forms of ‘militant’ cinema could no longer be sustained. Straub & Huillet shifted their dialectical dispositive to a lyrical one (Dalla Nuba alla Resistenza, 1978). Rocha put his remaining energies into a self-destructing anti-symphony (A Idade da Terra, 1980). Oshima’s Brechtian articulations of revolutionary desire in the light of political repression gave way to portrayals of the exasperation and impotence of desire (Ai no corrida, 1976). As if desire could no longer be thought of as a mode of resistance, but only one of escapism: is this not the sentiment that has been haunting us since the end of the 1970s? The overflow of democratic mass individualism, that which the 1968 generation was supposedly seeking all along, has allegedly culminated in an infinite drift of narcissistic consumers who do not care for anything but the instant satisfaction of their own needs and desires: this is the narrative that the contemporary left has embraced. The same criticism that used to denounce the society of the spectacle and the mythology of consumer ideologies in view of possible change had started to turn on itself, trapping itself in an endless vicious cycle in which the power of the market can no longer be distinguished from the power of its denunciation. As if everything equals everything else, and all resistance is futile. As if we are now all political realists, stuck in an endless refrain of consensual melodies, stuck with the ‘way things are’, this ‘natural order of things’ that the character of Ned Beaty so vigorously evangelized in Network (1976).

‘But we can not continue much longer on the way of disillusion’, wrote Daney towards the end of his life. Despite his growing disenchantment with the dissolution of the cinema that he had so much cared for, the ciné-fils still put his wager on optimism. ‘Between the spectacle and the lack of images, is there a place for “art to live with images”, at the same time demanding them to be “humanly” comprehensive (to better know what they are, who makes them and how, what they can do, how they retroact on the world) and keep at their core this remnant that is in-human, startling, ambiguous, on the verge?21’ With Daney, we can ask how we might gain a renewed trust in the power of the image. How can we get out of the fatalistic scepticism that the ‘society of disdain’ has bestowed on us? Can the history of militant cinema, beyond all rhetoric, still infuse us with a much-needed sense of risk, adventure and emancipatory potential? It is clear to us now that the belief in the causal relations between affection, understanding and action, which once provided the basic foundation for militant cinema, is no longer valid: the lack of any horizon of change has made sure of that. It has also become increasingly clear that the overwhelming feelings of disorientation and disappointment, the sense of something lacking or failing that arises from the realization that we inhabit a violently unjust world, all too easily sweep us away into the never-ending depths of fear and nihilism. The challenge, then, is to break with this dominant discourse that tells us that any notion of politics is constantly undermined by disillusionment. Now that cinema, being unsure of its own politics, is once again encouraged to intervene in the absence of the proper political, the question is how it can generate a new power of affirmation, one that is consistent with the interruption of the logic of resignation evidenced by recent uprisings, one that breaks with the febrile sterility of the contemporary world. In a time when capitalism has colonized most of our dream life, can cinema once again become a laboratory of distant dreams, invigorating a new sense of the impossible, something to hold on to, hold on dearly?

Stoffel Debuysere

In the framework of “The Fire Next Time” and “Figures of Dissent (Cinema of Politics, Politics of Cinema)” (KASK/HoGent)

1. Serge Daney, ‘Fonction critique’, Cahiers du cinéma 250, May 1974

2. Glauber Rocha, ‘Beginning at Zero: Notes on Cinema and Society’, The Drama Review, Winter 1970

3. Godard par Godard, éditions de l’Etoile – Cahiers du cinéma, Paris, 1985, p. 348

4. Trevor Stark, ‘Cinema in the Hands of the People: Chris Marker, the Medvedkin Group, and the Potential of Militant Film’, October 139, Winter 2012

5. Quoted in Le Gai Savoir (1969)

6. See Jacques Rancière’s analysis: ‘Le rouge de la Chinoise’, Trafic 18, spring 1996

7. Godard quoted in James Roy McBean, ‘See You at Mao: Godard’s Revolutionary British Sounds’, Film Quarterly, 1970-71, pp15-23

8. Bertold Brecht, quoted by Walter Benjamin (1931)

9. Roland Barthes, Mythologies, 1957, pp. 68–69

10. Roland Barthes, ‘Writers, Intellectuals, Teachers’, 1971

11. Jean-Louis Comolli, Film/politique (2) L’Aveu: 13 propositions, Cahiers du Cinéma 224, October 1970

12. Serge Daney, Pascal Kane, Jean-Pierre Oudart, Serge Toubiana, ‘Une certaine tendance du cinema français’, Cahiers du Cinema 257, May-June 1975.

13. Jean-Luc Godard in Nouvel Observateur 388, April 1972

14. Rocha, ‘O último escândalo de Godard’, Manchete 928, 31 January 1970

15. Glauber Rocha, ‘Aesthetic of Dream’, presented at Columbia University in 1971

16. Pier Paolo Pasolini, ‘The Unpopular Cinema’, 1970.

17. G. Roy Levin, ‘Reclaiming our Past, Reclaiming our Beginning, interview with Robert Kramer and John Douglas’, Jump Cut 10-11, 1976

18. Pascal Bonitzer , ‘Lignes et voies : (Macadam à deux voies)’, Cahiers du cinema 266-267, May 1976.

19. Rainer Werner Fassbinder interviewed by Christian Brad Thomson

20. Serge Daney in conversation with Bill Krohn (1977)

21. Serge Daney, L’exercice a été profitable, monsieur, P.O.L, 1993, p. 210