In the context of the Courtisane Festival 2015 (1-5 April), in collaboration with Tate Modern & UCLA Film & Television Archive. Curated by Stoffel Debuysere.

What’s in a name, really? L.A. Rebellion is first of all a handy and appealing designation for something that might actually be both too momentous and too heterogeneous to contain in a name. Nevertheless, one is faced with some bare facts: at a particular time and place in American cinema history, a critical mass of filmmakers of African origin or descent together produced a rich and venturous body of work, independent of any entertainment industry influence. At this time, in this place, buzzing with the spirit of the civil rights movement and memories of past and future uprisings, these filmmakers – most of whom studied at UCLA in Los Angeles in the late 1960s to the late 1980s – committed themselves to depicting the lives of black communities in the U.S. and worldwide.

But can one really speak of a single “movement”? Is the word “rebellion” appropriate here? And what about the notion of a “black cinema”? Are these even the right questions to ask? Perhaps we could better ask: what is it that we can do with these films today, in this peculiar time, in this particular place? If these films still resonate so strongly with us, it is perhaps because they refuse to be contained in an imposed framework, and instead choose to explore the off-track and the off-kilter, the unsettled and unsettling in the everyday. Perhaps it is because they do not profess to disclose secrets beyond the surface of what is present, and instead make sense of what is too close to see: the internal ghetto of emotional devastation, suffocation, exhaustion, trepidation, disorientation. Perhaps it is because they are about making common cause with a sense of brokenness, without offering a prescription for repair, about finding resilience and dignity in a sentiment that is no stranger to any of us: vulnerability. And perhaps this is how these films, in all their diversity and richness, find resonance in another sentiment long considered useless, but which has in recent years sparked a new sense of collective engagement and imagination. It is called indignation.

L.A. Rebellion: Creating a New Black Cinema is a project by UCLA Film & Television Archive developed as part of Pacific Standard Time: Art in L.A. 1945-1980. The original series took place at UCLA Film & Television Archive in October – December 2011, curated by Allyson Nadia Field, Jan-Christopher Horak, Shannon Kelley and Jacqueline Stewart.

Special thanks to George Clark, Steven Hill and Todd Wiener, without whom this program would not have been possible.

In the framework of the research project “Figures of Dissent” (KASK/Hogent).

———————————————————————————————–

Thursday, April 2, 2015 – 13:00 KASKcinema

Passing Through

Larry Clark, US, 1977, 16mm, b&w, 111′

Eddie Warmack, an African American jazz musician, is released from prison for the killing of a white gangster. Not willing to play for the mobsters who control the music industry, including clubs and recording studios, Warmack searches for his mentor and grandfather, the legendary jazz musician Poppa Harris. Larry Clark’s film theorizes that jazz is one of the purest expressions of African American culture. However, jazz is now hijacked by a white culture that brutally exploits jazz musicians for profit. Following the opening credit sequence as an homage to jazz and jazz musicians, the film repeatedly returns to scenes of various musicians improvising jazz, as well as flashback scenes in which Poppa teaches Warmack to play saxophone. It is the Africanism of Poppa, as the spiritual center of Passing Through that ties together Black American jazz and the liberation movements of Africa and North America. The film’s final montage incorporates shots of African leaders with a close- up of Poppa’s eye and close-ups of Black hands holding the soil, thus semantically connecting jazz, Africa and the earth in one mystical union. (Jan-Christopher Horak)

———————————————————————————————–

Thursday, April 2, 2015 – 15:30 KASKcinema

Killer of Sheep

Charles Burnett, US, 1977, DCP, b&w, 81′

Like a slow crescendo, Killer of Sheep became one of L.A. Rebellion’s most widely celebrated films over the course of many years. Although it was preserved in 35mm in 2000, it took seven more years to clear the music rights for commercial distribution. The momentum might have waned if it wasn’t for the gravitational force of filmmaker Charles Burnett’s captivating vision of Watts in post-manufacturing decline, a community heroically finding ways to enjoy and live life in the dusty lots, cramped houses and concrete jungles of South Los Angeles. The focus is slaughterhouse worker Stan (novelist, playwright and actor Henry Gayle Sanders) whose dispiriting job wears him down, alienates him from his family and becomes an unspoken metaphor for the ongoing pressures of economic malaise. Drawing inspiration from Jean Renoir’s sun-dappled and racially sensitive The Southerner (1945) as well as the poetic documentaries of Basil Wright (one of Burnett’s teachers at UCLA), Killer of Sheep achieves a deeply felt intensity with nonprofessional actors and handheld location shooting. The film also creates a sense of immediacy and spontaneity (though much of Sheep was storyboarded) as well as quiet moments of humor and despair. Burnett finds lyricism by combining quotidian images – children playing on rooftops or Stan and his wife slow-dancing in their living room – with a highly evocative soundtrack of African American music. It’s both a time capsule and a timeless, humanist ode to urban existence. (Doug Cummings)

———————————————————————————————–

Thursday, April 2, 2015 – 20:00 Paddenhoek

Bless Their Little Hearts

Billy Woodberry, US, 1984, 35mm, b&w, 84′

Billy Woodberry’s film chronicles the devastating effects of underemployment on a family in the same Los Angeles community depicted in Killer of Sheep (1977), and it pays witness to the ravages of time in the short years since its predecessor. Nate Hardman and Kaycee Moore deliver gut-wrenching performances as the couple whose family is torn apart by events beyond their control. If salvation remains, it’s in the sensitive depiction of everyday life, which persists throughout. By 1978, when Bless’ production began, Burnett, then 34, was already an elder statesman and mentor to many within the UCLA film community, and it was he who encouraged Woodberry to pursue a feature length work. In a telling act of trust, Burnett offered the newcomer a startlingly intimate 70-page original scenario and also shot the film. He furthermore connected Woodberry with his cast of friends and relatives, many of whom had appeared in Killer of Sheep, solidifying the two films’ connections. Yet critically, he then held back further instruction, leaving Woodberry to develop the material, direct and edit. As Woodberry reveals, “He would deliberately restrain himself from giving me the solution to things.” The first-time feature director delivered brilliantly, and the result is an ensemble work that represents the cumulative visions of Woodberry, Burnett and their excellent cast. (Ross Lipman)

Followed by a DISSENT! talk with Billy Woodberry and Barbara McCullough

———————————————————————————————–

Friday, April 3, 2015 – 13:00 KASKcinema

L.A. Rebellion – short films

As Above, So Below

Larry Clark, US, 1973, 16mm, 52′

Larry Clark’s astonishing short feature evokes a Black community in crisis, divided between a narcotizing church that preaches quietism, depicted with savage Brechtian satire that nevertheless evinces a hint of affection, and militant struggle that is both in response to and inspired by U.S. military interventions throughout the Third World. “Like The Spook Who Sat By the Door and Gordon’s War, As Above, So Below imagines a post-Watts rebellion state of siege and an organized Black underground plotting revolution. With sound excerpts from the 1968 HUAC report ‘Guerrilla Warfare Advocates in the United States,’ As Above, So Below is one of the more politically radical films of the L.A. Rebellion.” (Allyson Nadia Field)

Four Women

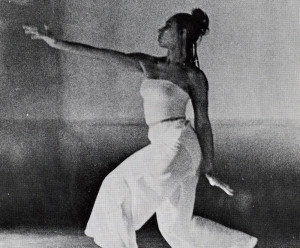

Julie Dash, US, 1975, 16mm, colour, 7′

Set to Nina Simone’s stirring ballad of the same name, Julie Dash’s dance film features Linda Martina Young as strong “Aunt Sarah,” tragic mulatto “Saffronia,” sensuous “Sweet Thing” and militant “Peaches.” Kinetic camerawork and editing, richly colored lighting, and meticulous costume, makeup and hair design work together with Young’s sensitive performance to examine longstanding Black female stereotypes from oblique, critical angles. (Jacqueline Stewart)

Water Ritual #1: An Urban Rite of Purification

Barbara McCullough, US, 1979, 35mm, b&w, 6′

Made in collaboration with performer Yolanda Vidato, Water Ritual #1 examines Black women’s ongoing struggle for spiritual and psychological space through improvisational, symbolic acts. Shot in 16mm black-and-white, the film was made in an area of Watts that had been cleared to make way for the I-105 freeway, but ultimately abandoned. Though the film is set in contemporary L.A., at first sight, Milanda and her environs (burnt-out houses overgrown with weeds) might seem to be located in Africa or the Caribbean, or at some time in the past. Structured as an Africanist ritual for Barbara McCullough’s “participant-viewers,” the film addresses how conditions of poverty, exploitation and anger render the Los Angeles landscape not as the fabled promised land for Black migrants, but as both cause and emblem of Black desolation. (Jacqueline Stewart)

Child of Resistance

Haile Gerima, US, 1972, 16mm, colour, 36′

Inspired by a dream Haile Gerima had after seeing Angela Davis handcuffed on television, Child of Resistance follows a woman (Barbara O. Jones) who has been imprisoned as a result of her fight for social justice. In a film that challenges linear norms of time and space, Gerima explores the woman’s dreams for liberation and fears for her people through a series of abstractly rendered fantasies. (Allyson Nadia Field)

The Pocketbook

Billy Woodberry, US, 1980, 35mm, 13′

In the course of a botched purse-snatching, a boy comes to question the path of his life. Billy Woodberry’s second film, and first completed in 16mm, adapts Langston Hughes’ short story, Thank You, M’am, and features music by Leadbelly, Thelonious Monk and Miles Davis. (Ross Lipman)

———————————————————————————————–

Friday, April 3, 2015 – 16:00 KASKcinema

Bush Mama

Haile Gerima, US, 1975, 16mm, b&w, 97′

Inspired by seeing a Black woman in Chicago evicted in winter, Haile Gerima developed Bush Mama as his UCLA thesis film. Gerima blends narrative fiction, documentary, surrealism and political modernism in his unflinching story about a pregnant welfare recipient in Watts. Featuring the magnetic Barbara O. Jones as Dorothy, Bush Mama is an unrelenting and powerfully moving look at the realities of inner city poverty and systemic disenfranchisement of African Americans. The film explores the different forces that act on Dorothy in her daily dealings with the welfare office and social workers as she is subjected to the oppressive cacophony of state-sponsored terrorism against the poor. Motivated by the incarceration of her partner T.C. (Johnny Weathers) and the protection of her daughter and unborn child, Dorothy undergoes an ideological transformation from apathy and passivity to empowered action. Ultimately uplifting, the film chronicles Dorothy’s awakening political consciousness and her assumption of her own self- worth. With Bush Mama, Gerima presents a piercing critique of the surveillance state and unchecked police power. The film opens with actual footage of the LAPD harassing Gerima and his crew during the film’s shooting. (Allyson Nadia Field)