DRAWN TO LIFE

reanimating the animate

Maison des Cultures Saint-Gilles, Belgradostraat 120, Brussels. 25 & 27 November 2008

Film and video program in the context of ‘SE JETER À L’EAU’, an event organised by Atelier Graphoui.

Curated by Stoffel Debuysere and María Palacios Cruz, in cooperation with Courtisane.

“animate … v.t…. [< L. animatus, pp. of animare, to make alive, fill with breath < anima, air, soul]. l. to give life to; bring to life. 2. to make gay, energetic, or spirited. 3. to inspire. 4. to give motion to; put into action: as, the breeze animated the leaves."

We all know: animation is a form of cinema. And yet, one could argue that all cinema is in fact animation, and furthermore that life itself – anima – can be understood as cinema. Our existence, inscribed in perception, imagination and memory, is constantly animated, deformed, edited. The question is whether and how we can ourselves give form to our own experiences. Certainly, the incessant flow of images in which our daily lives are submerged seems to leave little room for analysis and intervention. Its intention is that of synthesis, of a continuous illusion of life. The world is thus objectivized, but inevitably doubled, devoid of its soul, “deanimated”. The artists and filmmakers in this program attempt to revitalize perception, offering an alternative or counterweight to the ways in which technological interfaces determine our relation to the world. At the crossroads between cinematographic codes and genres, these films and videos seek to dismantle the common a priori assumptions on animation film and its limitations. Fragments of collective and individual memories are redrawn, with pencils and pixels, light, movement and (algo)rhythms, in search of new possible relations between world and representation, image and subject, dream and data, the aesthetical and the political. Animation as re-animation.

———————————————————————————————————————————————————

PROGRAM 1

Tuesday 25.11.2008 20:00

“We know that behind every image revealed there is another image more faithful to reality, and in the back of that image there is another, and yet another behind the last one, and so on, up to the true image of that absolute, mysterious reality that no one will ever see.”

— Michelangelo Antonioni

Robert Breer

Fuji

US, 1974, 16mm, colour, sound, 10′

Bang!

US, 1986, 16mm, color, sound, 10′

Robert Breer has been at the forefront of experimental animation filmmaking for over half a century. His work, in which he explores the role that movement plays in understanding form and space, represents an important link between the abstract films of Hans Richter and Viking Eggeling and the avant-garde cinema tradition. “Once I avoided conventional narration and replaced it with real time”, he writes, “I could put the images together in non sequitur impositions. This might be what you call ‘daily seeing’. It might be similar to the visual and aural experience of ordinary daily life – collision of experiences”. Fuji is one of Breer’s experiences in the early 1970’s with primitive forms of rotoscoping, in which live action is redrawn image by image. Fragments of footage of a journey in Japan are transformed into a lyrical exploration of colour and form, constantly swayed between representation and abstraction, between images that refer to precise objects and alternative spaces, offering a new look at the everyday. Bang! is Breer’s most autobiographical work : an associative collage of nostalgic childhood memories and bitter-sweet contemplations.

Dirk de Bruyn

Rote Movie

AUS, 1994, 16mm, colour, sound, 12′

A road movie across the emotional landscapes of the filmmaker, whose inner monologue shares his reflections on his feelings of exile, trauma, loneliness and alienation. His state of mind is evoked by increasingly fragmented images – direct-on-film animation collage, rotoscoped animation and reworked photographic images. The material aspect of film becomes a metaphor for the devastating effect that mental stress has on the body.

Frank & Caroline Mouris

Frank Film

US, 1973, 16mm, colour, sound, 9′

“I treat objects in a very subjective way, and I treat subjects by themselves in a very objective way”, affirms Frank Mouris. He describes Frank Film as “that one personal film that you do to get the artistic inclinations out of your system before going commercial”. This animated autobiography is composed of more than 11.000 images collected from magazines and catalogues, which shift and mutate across the screen as Mouris recites a list of words beginning with the letter ‘f’. The words bounce off the images and generate an associative flow of memories, which Mouris recounts on a second track, interwoven with the recitation. The result is an obsessive and mesmerizing collage, which film critic Andrew Sarris described as “a nine-minute evocation or America’s exhilarating everythingness”.

Stuart Hilton

Six weeks in June

UK, 1998, video, b/w, sound, 6′

“11,000 miles across the USA and back in a transit van with a rock and roll band, a pencil, a stack of A6 paper and 6 weeks in June to do it”. Stuart Hilton scribbles his films in a seemingly careless way, almost as if the doodles from his notebook jumped off the pages and started to move spontaneously. The simplicity of his technique seems to rightly feed the imagination. The traces of landscapes, human figures and objects that unfold in Six weeks in June, capture perfectly the feeling of restlessness and detachment that comes with living “on the road”. The “musique concrète” collage of found sounds and conversation fragments adds an extra dimension to the impression of “daily seeing”, as Robert Breer calls it. Image and sound sway from one to the other, separated and asynchronous but nevertheless inevitably linked in a continuous game of attracting and rejecting.

Bob Sabiston

Snack and Drink

US, 1999, video, colour, sound, 3’40

Bob Sabiston invented the Rotoshop software in the 1990’s to make rotoscoping– manually tracing and redrawing existing images – possible for artists working on video. In the current image culture it is no longer possible to determine what is “animated” and what isn’t, this technology being a good example of how digital video and computer animation have the same potential when it comes to representation. Snack and Drink is one of the early experiments with the software, based on a short documentary about an autistic teenager. The image material was coloured and stylized by a dozen of animators, giving it a dreamlike quality. A few years later, Sabiston would use the same technique in films like Richard Linklater’s Waking Life (2001) and A Scanner Darkly (2004), as well as The Five Obstructions (2003) by Lars Von Trier en Jørgen Leth .

Josh Raskin

I met the Walrus

CA, 2007, video, colour, sound, 5’15

“In 1969, a 14-year-old Beatle fanatic named Jerry Levitan, armed with a reel-to-reel tape deck, snuck into John Lennon’s hotel room in Toronto and convinced John to do an interview about peace. 38 years later, Jerry has produced a film about it. Using the original interview recording as the soundtrack, director Josh Raskin has woven a visual narrative which tenderly romances Lennon’s every word in a cascading flood of multipronged animation. Raskin marries the terrifyingly genius pen work of James Braithwaite with masterful digital illustration by Alex Kurina, resulting in a spell-binding vessel for Lennon’s boundless wit, and timeless message.” Josh Raskin: “I just wanted to literally animate the words, unfurling in the way I imagined they would appear inside the head of a baffled 14-year-old boy interviewing his idol.”

LEV (Levni R. Yilmaz Esq)

Tales Of Mere Existence (selection)

US, video, b/w, sound, 5′

“Tales Of Mere Existence is not necessarily about interesting stories, It is what it’s title indicates, anecdotes about the gloriously mundane. Everyday stories told not by the Devil on your right shoulder or the Angel on your left, but the voice in the middle of your head that doubts himself, questions everything, and sometimes doesn’t let you get out of bed. An unseen narrator tells the stories in a monotone voice, while his doodled illustrations come together on the screen. The stories deal with issues such as Sex, identity, and social confusion and just about anything else you would have written in your journal in High School. Tales Of Mere Existence goes for laughs in fearless ways that shock you even as you nod your head in recognition” Taylor Jessen, Animation World Network

Jonathan Hodgson

Night Club

UK, 1983, 16mm, colour, sound, 6′

Jonathan Hodgson, one of the most celebrated filmmakers in the rich British animation film scene, made this film when he was still a student at the Royal College of Art. We can already find here what would later become the main characteristics of his work, which sets its basis on the observation of the everyday and a preference for the spontaneous and the associative, in order to explore the tension between stasis and movement. “Nothing I’ve ever done has really been based on escapism”, he explained in an interview, “It’s always been about life”. Night Club is based on a series of sketches that Hodgson did in Liverpool drinking pubs. An observation of human behaviour in a social situation, hinting at the loneliness felt by the individual lost in the crowd.

Sky David

Field of Green: A Soldier’s Animated Sketchbook

US, 2007, 35mm to video, colour & b/w, sound, 8′

Like all “good Texan boys”, Sky David enlisted in the U. S. army at the end of the 1960’s. He documented his experiences of the Vietnam war in a sketchbook. These drawings remained untouched for over 30 years until he decided to make an animation film based on them. In the words of Cathy Caruth: “Trauma is not locatable on the simple violent or original event in an individual’s past, but rather in the way that its very unassimilated nature – the way that it is precisely not known in the first instance – return to haunt the survivor later on”. The film carries the scarred memory of a North Vietnamese soldier in whose rucksack David found delicate watercolours and pencil drawings. This film, according to David “happens when the “enemy” becomes a human being identical as myself. It is the film that this unknown would have made had he survived”.

———————————————————————————————————————————————————

PROGRAM 2

Thursday 27.11.2008 20:00

“The worship of pattern, the one and only, at the expense of the subject matter from which it comes. How do we rediscover it, and how do we impart or describe it? The ultimate challenge of the future – to see without looking: to defocus! In a world where the media kneel before the altar of sharpness, draining life out of life in the process, the DEFOCUSIST will be the communicators of our era – nothing more, nothing less!”

— Lars von Trier

Kota Ezawa

The Simpson Verdict

GE/US, 2002, video, colour, sound, 3′

In his videos, slide projections and photo prints, Kota Ezawa re-animates iconic moments from his personal and cultural history. He describes this practice as a form of “video archeology”. Using primitive graphic software, he manages to extract, from the many layers of mediation, the essence of the original material – very often images that have been so frequently repeated that we seem to think we know all about them. As he says, “Stylization can transform an image from a means of representation to a direct solicitation of viewer’s emotion”. The Simpson Verdict is 3 minute video-animation of the final moments of O.J. Simpson’s trial in 1995 for the murder of his wife and her friend, as the verdict is being read out. (Note : to the surprise and dispair of many, Simpson was declared innocent, partly because many of the evidence photographs weren’t judged “truthful” enough by the jury. “Photography is no longer evidence for anything”, as read a 1982 announcement from Lucasfilm)

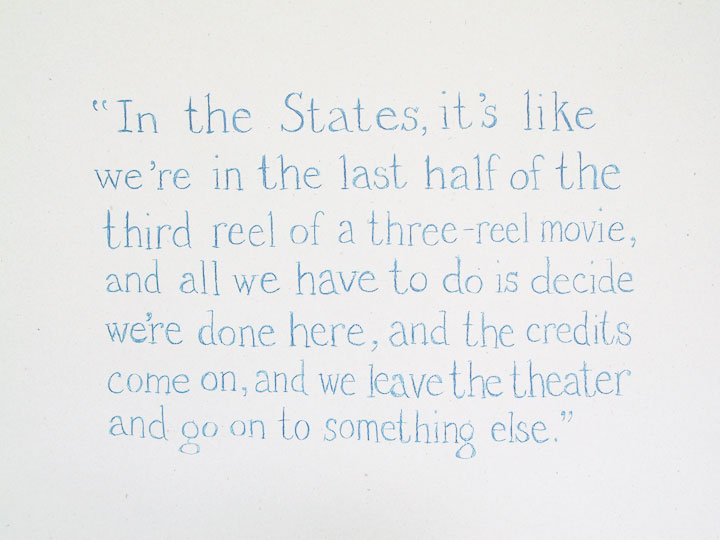

Jenny Perlin

Box Office

US, 2007, 16mm, b/w, silent, 2’25

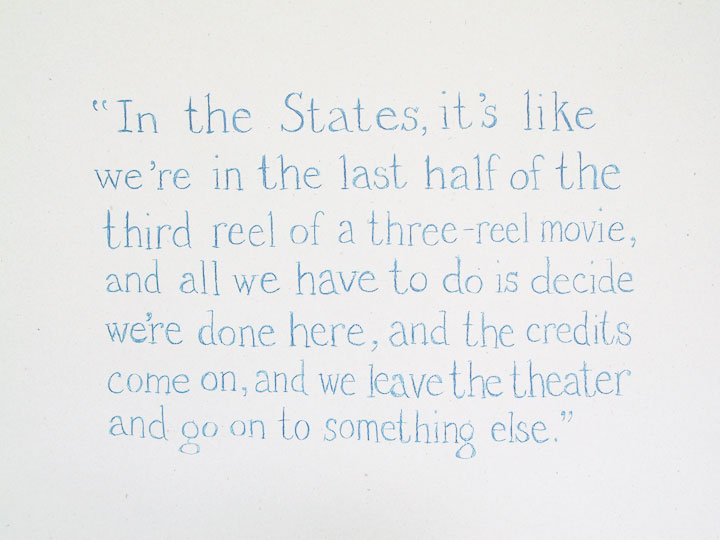

Jenny Perlin: “In each aspect of my practice I take a close look at the ways in which social machinations are reflected in the smallest aspects of daily life. Whether it is copying a receipt from Wal-Mart, a headline from Reuters, or filming documentary-style interviews at the corner store, my interest is in the ways in which the sweeping statements of “History” affect specific details of human experience”. This short, hand-drawn animated film begins with a quote by Ryan C. Crocker, the current U.S. Ambassador to Iraq. In July, 2007, the New York Times quoted Crocker as comparing the current war in Iraq to a three or five-reel movie, depending on where one is living. In contrast to this quote, a list of the top-ten grossing films at the U.S. box office from the same day presents itself onscreen, along with other animated panels of related drawings that function as an associative commentary.

Ken Jacobs

Capitalism : slavery

US, 2007, video, b/w, silent, 3′

In the words of Ken Jacobs : “An antique stereograph image of cotton-pickers, computer-animated to present the scene in an active depth even to single-eyed viewers. Silent, mournful, brief.” The work of Ken Jacobs, a key figure in the post-war experimental film world, is often concerned with the cinematographical reanimation of historical image material. In many of his films and performances he dissects and manipulates existing film material, deconstructs each sequence and gesture, applies himself to texture and space and choreographs as a self-appointed “cine-puppeteer” a secondary discourse of forgotten and explored time. In his Nervous System performances he creates, with the help of two modified film projectors, so-called “eternalims” : “unfrozen slices of time, sustained movements going nowhere and unlike anything in life.” Using external shutters, which interrupt the light of both projectors alternately, a new cinematographic space is created, somewhere between 2D and 3D. This effect, similar to parallax in binocular vision – in which objects and figures appear to be at the same time in a state of suspenstion and caught in a continuous movement – has been successfully transposed to the digital domain in his recent video work. “3-D without spectacles (as if people would watch flat movies). Pummeling exercises in cinematic insistence: Let the image prevail! “.

Cathy Joritz

Negative Man

GE/US, 1985, 16 mm, b&w, sound, 2′ 30″

Give AIDS the Freeze

GE/US, 1991, 16mm, b/w, sound, 2′

Rosalind Krauss wrote in reference to the work of Cy Twombly : “the formal character of the graffito is that of a violation, the trespass onto a space that is not the graffitist’s own, the desecration of a field originally consecrated to another purpose, the effacement of that purpose through the act of dirtying, smearing, scarring, jabbing”. This could also be said of the films of Cathy Joritz, who uses various direct-on-film animation techniques to penetrate and appropiate the existing images on the celluloid. In Negative Man and Give Aids the Freeze, Joritz uses this technique to comment sarcastically on two television speeches, of a TV presenter and a psychologue respectively. In a time span of a few minutes they become the objects of a continuous transformation that is draped on them like a second, celluloid skin. Joritz’s drawings not only serve to adjust the image but also as a way to unmask the representation of authority.

Paul Glabicki

Diagram Film

US,1978, 16mm, colour, sound, 14′

“Perception is a tool” explains Paul Glabicki. His work is driven by an obsessive inclination towards analyzing his own experiences, combined with a personal research on form, time and space. His drawings, paintings, films and computer animations reflect a personal perpective that filters and processes information, encodes layers of meaning and representation, and dissects relationships of parts to the whole. For Glabicki, one single image or object can generate an endless chain of new images, relationships, memories, experiences, and associations. In Diagram Film live-action and still images of objects and places are presented and then followed by animated diagrams that explain, transform or re-interpret what has just been seen. The result is a playful exploration of the borders between the abstract and the figurative, the rational and the irrational.

Jonathon Kirk

I’ve got a guy running

US, 2006, video, b/w, sound, 7’12”

When the images from the first Gulf War appeared in the international media, it became extremely difficult to make a distinction between “real” images and computer-generated ones. Since then, this development has had an enormous impact on the way we (de)code visual information. In this video, Jonathon Kirk explores the relation between cognition and recognition of war images, a relation that has been severely affected by the influence of simulation, surveillance and real-time media coverage. Images of a precision bombing, released by the U.S. Department of Defense to the glory of the American army and its weapon suppliers, are subject to algorithms, which gradually reveal the reality that lies beneath them.

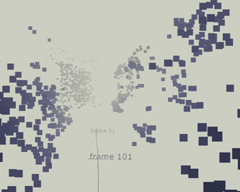

Dietmar Offenhuber

paths of g

AU, 2006, video, colour, sound, 1′

The long backwards tracking shot through a trench in Stanley Kubrick’s WWI drama Paths of Glory (1957) is reduced to pure geometry. Nothing is visible other than a matrix of rectangular figures and a line which follows the movement of the camera and counts off the spent frames. The soldiers’ corporality and the trench’s materiality are reduced to an abstract configuration of digital forms and values, surveyed by the camera’s mechanism – the single-frame transport, used for the first time during WWI, changing for once and for all the perception of war. In a certain way, this reduction gives a more accurate image of the first industrialized war in history than Kubrick’s original version. As Paul Virilio wrote in Guerre et cinéma: “as sight lost its direct quality and reeled out of phase, the soldier had the feeling of being not so musch destroyed as derealized and dematerializes, any sensory point of reference suddenly vanishing in a surfeit of optical targets”. It is precisely the conscious reduction within the film, the purely mechanical, geometric values which are able to reveal the true violence of this war. The fictionalized fact is not necessary, removing the sense from existing images suffices to return to the historically factual qua ‘techno-imagination’ (Vilém Flusser). The viewer sees less but learns more.

Persijn Broersen & Margit Lukács

Prime Time Paradise

NL, 2004, video, colour, silent, 11′

“We consume images at an ever faster rate and images consume reality”, wrote Susan Sontag in On Photography. While in that book she pled passionately for an “economy of images”, she would later admit that it could no longer be spoken of . “In our digital hall of mirrors, the pictures aren’t going to go away”, she wrote when the images of Abu Ghraib were published. “Yes, it seems that one picture is worth a thousand words. And there will be thousands more snapshots and videos. Unstoppable.” However, the potential force of images can be diminished by their overproduction and by the incessant search of dramatic impact, in a culture in which the shock effect appears as an stimulus for consumption. “How do you deal with the constant flow of information : do you turn yourself away or do you try to create a new, meaningful structure ?” Margit Lukács asks herself. In Prime Time Paradise Broersen and Lukács have frozen a number of images from the daily flow of news reports in a spatial collage, an infernal media landscape of conflict, death and depravation.The impact is postponed, the gaze renewed.

Karl Tebbe

Infinite Justice

GE, 2006, video, colour, sound, 2′

“La Guerre du Golfe n’a jamais eu lieu” (The Gulf War did not take place), affirmed Jean Baudrillard at the beginning of the 1990’s. The war he was referring to was a television war, produced as a soap series in which news announcements became trailers, content was delivered in daily episodes, and the show was perpetuated by a number of film sequels and video games. Nothing has changed much since then. Whoever controls the images, controls the war. “War-making and picture-taking are congruent activities”, wrote Susan Sontag about the current war in Iraq. “Television, whose access to the scene is limited by government controls and by self-censorship, serves up the war as images.” With Infinite Justice, Karl Tebbe deconstructs and interrogates the public image (and image experience) of war, embedded in the omnipresent television reality. Fragments from war reports shown on German television were re-animated frame by frame with “action figures” sold in the USA. “This isn’t Disney. Not Team America. This is war”.

Stephen Andrews

The Quick and the Dead

CA, 2004, video, color, sound, 1’30”

According to Stephen Andrews, “the cracks sometimes mean more than the picture”. The Canadian artist is aware of the erosion of the image as a form of testimony. With his drawings and videos, he seeks to “slow down the gaze”, through a process of reanimation. Existing images and sequences are reconstructed by hand and meticuously recreated as pencil drawings, underlining the tension between the subjectivity of the drawer and the objectivizing role that digital visual technology plays. “I have always been fascinated by technology because it can never do what the hand can do, which is to fail miserably. The machine can draw a perfectly straight line – the hand refuses. Technology thus becomes a prosthesis for our shortcomings. When I in turn render by hand what the machine has wrought, my intention is to decipher the medium’s message”. The Quick and the Dead is based on a short clip that Andrews found on the Internet – one of the many dehumanized images of “collateral damage” that have reached us from Iraq these past years. “A moment of random death is given consideration through the human act of retouching” (Atom Egoyan).

Carolee Schneemann

Viet Flakes

US, 1965, 16 mm film to video, bIw, sound, 7′

Viet Flakes was conceived as the central part of Snows, a Carolee Schneemann performance in reaction to the war in Vietnam. A shocking reflection on the violence and representation of war, the film is built as an obsessive collage of photographic images taken from magazines and newspapers, “animated” by Schneemann’s Super 8 camera’s travelling “within” the images. The visual fragmentation is heightened by a sound collage by James Tenney. “Schneemann constructs a sense of the violent dimensions of the war at a time when the true impact of the Vietnam War was scarcely understood. Using film as a plastic medium to create a metadocument, Schneemann gives the viewer a sense of the dimension of these atrocities, puts the war in a human perspective and goes directly to the source of the catastrophe, much in the way that the great Greek dramatists were able to situate tragedy so convincingly” (Robert C. Morgan).

———————————————————————————————————————————————————

Thanks to Sky David, Dirk de Bruyn, Kota Ezawa, Jonathan Hodgson, Ken Jacobs, Jonathon Kirk, LEV, Frank & Caroline Mouris, Jenny Perlin, Bob Sabiston, Karl Tebbe, Mike Sperlinger (LUX), Christophe Bichon & Emmanuel Lefrant (Lightcone), Dominic Angerame (Canyon), Michaela Grill (Sixpack), Wanda vanderStoop (Vtape), Theus Zwakhals (Montevideo), Rebecca Cleman (EAI), Jeff Crawford (CFMDC), : jerry levitan, chris kennedy (vtape), Edwin Carels, Pieter-Paul Mortier (STUK), Dirk Deblauwe (Courtisane), Brett Kashmere, Jacques Faton (ERG / Atelier Graphoui)