The Fire Next Time

Afterlives of the militant image

3-4 April 2014. KASKcinema, KIOSK & Minard, Gent, Belgium

There was a time when cinema was believed to make a difference, to be able to act as a weapon in struggle, to operate as a realm of discord. The so-called ‘militant cinema’ was not only considered as a tool to bear witness but also to intervene in the various political upheavals and liberation movements that shook the world in the 1960s and ‘70s. What remains of this unassailable alliance between cinema and politics? After the flames had died down, all that seemed to be left was a wreckage of broken promises and shattered horizons. Today it feels like we have been living through a long period of disappointment and disorientation, while the sense of something lacking or failing is spreading steadily. An overwhelming melancholy seems to have taken hold of our lives, as if we can only experience our time as the ‘end times’, when the confidence in politics is as brittle as our trust in images. Perhaps that is why, for those who came after, there is a growing tendency to look back at an era when there was still something to fight for, and images were still something to fight with. Can a re-imagining of old utopian futures shed a new light on our perceived dead-end present, in view of unexpected horizons? Can an understanding of past dreams and illusions lead to reinvigorated notions of responsibility, commitment and resistance? Can a dialogue with the period in question help us to find the very principles and narratives capable of remedying its impasses? And how can this questioning help us to think about how cinema, unsure of its own politics, can be ‘political’ today? In light of a potential rebirth of politics, would it still be possible for the art of cinema to appeal to the art of the impossible?

In the framework of the research project ‘Figures of Dissent’ (KASK/HoGent) and the EU project ‘The Uses of Art’ (confederation L’Internationale), in conjunction with ‘L’œil se noie’, an exhibition of work by Eric Baudelaire and Mathieu Kleyebe Abonnenc (KIOSK, 05/04 – 15/06/2014) and the Courtisane Festival (02-06/2014). With the support of the research groups S:PAM & PEPPER (UGent), art centre Vooruit, BAM institute for visual, audiovisual and media art, Eye on Palestine, Embassies of France & Mexico.

Research Tumblr Page: fire-next-time.tumblr.com

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

THURSDAY 3 APRIL

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Introduction

Stoffel Debuysere

I just wanted to say a few words about ‘The Fire Next Time’ and some of the challenges we would like to engage with in the coming days. It has become clear for all of us that in the past few years there has been a resurgence of interest in notions and practices of miltancy, and more particular of what is called “militant cinema”, which generally indicates a pretty heterogeneous landscape of film making and thinking that accompanied the various struggles for emancipation and liberation in the 1960’s and the beginning of the 1970’s. It is a tendency you can see in the programs of so many festivals and cinema venues nowadays, but also in the spaces of contemporary art, where many artists (or curators) attempt to reboot or revisit some of the issues and tensions, presences and absences that characterized this landscape.

There are many possible as to why this revalidation is happing right now. Perhaps, as people like Alain Badiou have suggested, in times of disquiet, riots and uprisings such as ours, these models of thought and action can serve as potential source of inspiration, as some kind of historical poems that can give us new courage. Perhaps they can allow us to react now that we are, as we are told over and over again, in the grip of despair, after the waning of so many dreams and desires that framed and animated the past politics of emancipation, including its anti-colonial and socialist forms. And then perhaps, now that it seems that there are no more determined horizons or programs to guide the current struggles, this looking back might help us to start trusting in the actions we might take in the here and now.

So on one hand there is the question of our current relationship to these paradigms of militancy, as echoes from a certain era, and the affiliated assumptions in regards to the relation between art and life, reality and appearance, theory and practice. There is the question of how to look at these film work from where we are now, but on the other hand it might be interesting to consider how these films look back at us too, how these films are not only historical objects from a faded past, but how they are still alive somehow, alive with sensation, affect, thought, and that they can perhaps, ultimately, make us feel alive in return.

So this program of interventions and screenings might provide an opportunity to think about the representation of politics, and also how some ideas and words that once demarcated the battlegrounds – such as revolution, proletariat, commitment – can be released from their sediment and given back their untimely charge, but it can also be a chance to rethink the politics of representation, the links between intention and outcome, between what is represented and the form that it has been given, and how this form could be appropriated by each and every one of us.

And then, it seems to me that as much as this broad landscape of militant cinema can be used as an exemplary terrain on which to think through aspects of the contemporary aporia of the crisis of politics, it can also be used as a stimulus to counter the melancholia that characterizes a lot of the critical thinking of the past decades – including the film critical thinking. These, for me, briefly, are some of the stakes and the challenges of these coming two days, and I hope that we will be able to, if not provide satisfactory answers, at least probe a few pertinent questions.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

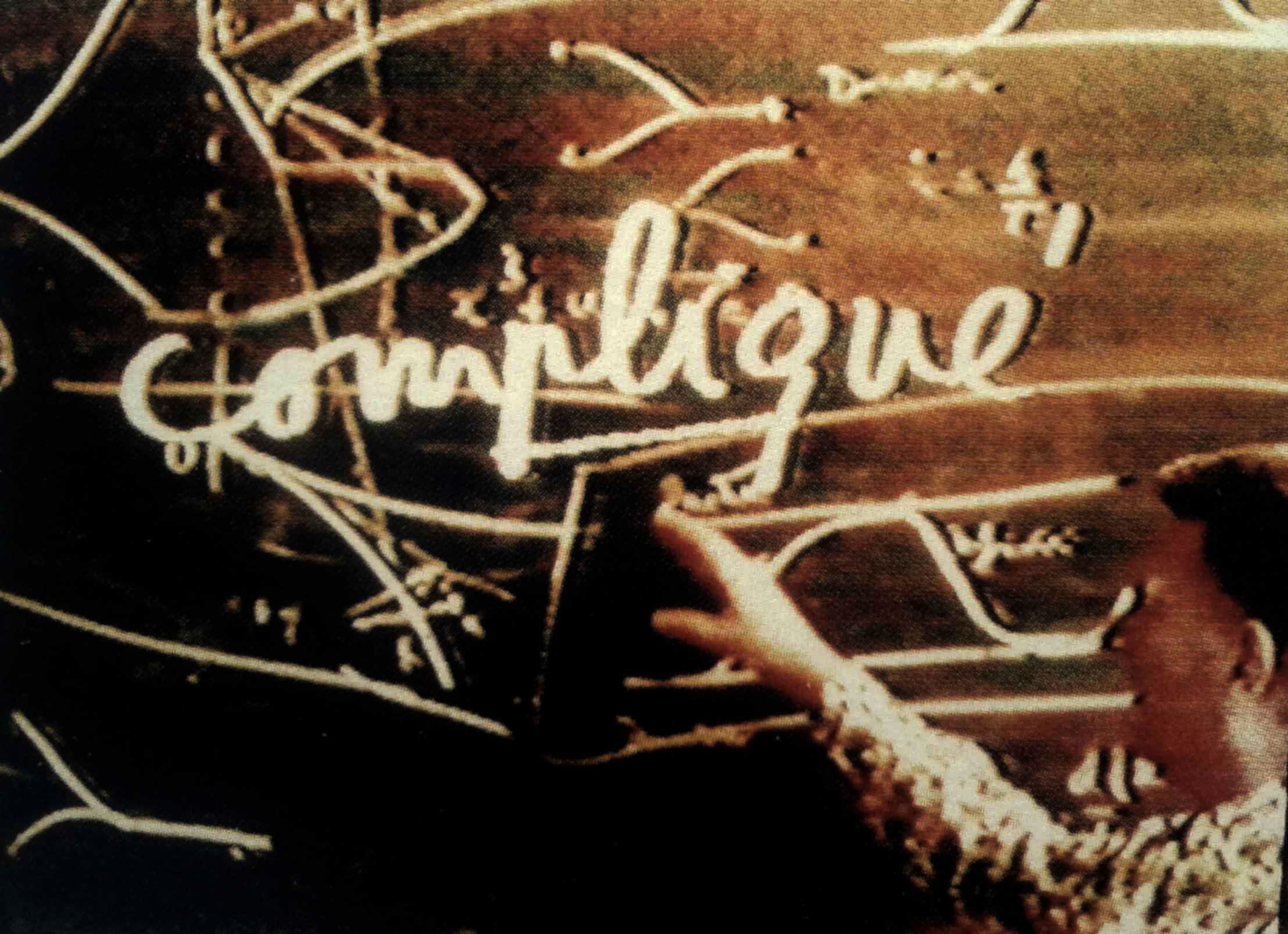

Militant Cinema: from Third Worldism to Neoliberal Sensible Politics

Irmgard Emmelhainz

Jean-Luc Godard’s Ici et ailleurs (1969-1974) as well as Chris Marker’s Le fond de l’air est rouge (1977) crystallize the histories of militant engagement and political filmmaking in the 1960s, a time in which Marxism was a vehicle for cultural as well as actual revolution here and elsewhere. From both films, lessons about this era of militantism can be drawn. Moreover, they announce a turn in the 1970s and 1980s toward minority politics (tied to de-colonization struggles) and humanitarization –which implies an ethical, as opposed to political relationship to the elsewhere, as well as the utopia of globalization. Bearing this in mind, Irmgard Emmelhainz will discuss the changes in the meaning of ‘politicization’ and political work from the 1960s from what is known today as ‘Sensible Politics’: a form of politicization active at the level of encoding unstable political acts in medial forms. Taking up Jean-Luc Godard’s plea for texts and poetry (inspired by Aristotle’s and Hannah Arendt’s understanding of political action as speech), in his film Notre musique, she will argue that most of the current politicized images are compensatory devices to the ravages caused by neoliberal reforms implemented worldwide in the past two decades.

Irmgard Emmelhainz is an independent writer and researcher based in Mexico City. In 2012, she published a collection of essays about art, culture, cinema and geopolitics: Alotropías en la trinchera evanescente: estética y geopolítica en la era de la guerra total (BUAP). Her work about cinema, the Palestine Question, art, culture and neoliberalism has been translated to French, English, Arabic, Turkish, Hebrew and Serbian. She is currently co-editing an issue dedicated to Mexico City of Scapegoat Journal, and teaching a course at the Esmeralda National School of Engraving and Painting in Mexico City.

Preceded by a screening of

Jean-Luc Godard & Anne-Marie Miéville,Ici et ailleurs (Here and Elsewhere) (FR, 1976)

Hito Steyerl, November (DE, 2004)

Guillermo Gomez-Pena, A Declaration of Poetic Disobediance (US, 2005)

THE FIRE NEXT TIME – Militant Cinema from KASK & CONSERVATORIUM on Vimeo.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Landscape/Media – an Investigation into the Revolutionary Horizon, Reloaded

Sabu Kohso & Go Hirasawa

The development of ‘Landscape Cinema’ and ‘Landscape Theory’ took place during the short period between the late ‘60s and early ‘70s in Japan, while the ‘60s movements were declining and the militant line of guerrilla warfare was rising. It embodied a collective effort to grasp a new horizon of revolutionary struggle and the possible location of its agency in the form of film productions and critical discourses. Initiated by an enigmatic film, AKA: Serial Killer (1969), the cinema/theory sought to confront ‘landscape’ as the main terrain for the power operation, seen by the gaze of a migrant worker. Then Red Army/PFLP – Declaration of World War (1971) was produced, embodying the second stage of the development in which tactical uses of reportage were juxtaposed over the everyday landscape of Palestine guerrillas. Although the film was produced in collaboration with Japan Red Army, it involves multiple messages including critical reflections on a broad orientation of Japan’s radical left. Screening the latter film, Hirasawa and Kohso seek to decode the problematic complexity of the cinema/movement, that tackles the mechanism of capture by landscape/media and the resistance therein, in order to approach the apocalyptic feature of planetary crises today.

Sabu Kohso is a writer and translator. Living in New York since 1980, he has published several books in Japan and Korea about urban space, radical politics, and the philosophy of anarchism, and has translated books by theorists such as David Graeber, John Holloway, Kojin Karatani and Arata Isozaki. After the Fukushima nuclear disaster, he co-edited the website jfissures.org, and has written several articles on the problematic of post-nuclear disaster society in English.

Go Hirasawa is a researcher at Meiji-Gakuin University working on underground and experimental films and avant-garde art movements in 1960s and ’70s Japan. His publications include Cultural Theories: 1968 (Japan, 2010), Koji Wakamatsu: Cinéaste de la Révolte (France, 2010), and Masao Adachi: Le bus de la révolution passera bientot près de chez toi ( France, 2012). He has organized several film programs on Japanese Underground Cinema.

Preceded by a screening of

Masao Adachi & Koji Wakamatsu, Sekigun-PFLP: Sekai Senso Sengen (The Red Army / PFLP: Declaration of World War) (JP/ Palestine, 1971)

THE FIRE NEXT TIME — Landscape/Media – an Investigation into the Revolutionary Horizon, Reloaded Sabu Kohso & Go Hirasawa from KASK & CONSERVATORIUM on Vimeo.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Destroy Yourselves as Our Bosses

Evan Calder Williams & Victoria Brooks

The connected talks of Evan Calder Williams and Victoria Brooks develop a feminist history of, and approach to, militant cinema from 1973 to 1983. In particular, they focus on critiques, both filmed and written, of how even allegedly radical movements reproduced a hierarchy of “legitimate” concerns that consistently framed the issues and modes of struggle posed by women as secondary to the cause at hand. This sidelining and its proprietary relation to politics has a history inextricable from labor movements themselves, but it becomes particularly visible with how practices of cinema directly engaged in social struggles negotiate what is literally foregrounded, drawn forth, or edited out. The first talk focuses on the Italian situation in the mid-’70s, considering “free newsreel” projects and experimental documentaries and reading their recurrent focus on the factory and piazza through the fierce critique articulated by Italian communist feminism in those same years. The second talk deals with films focused on women’s relation to factory and mining struggles in Ontario. These films, including those by Sophie Bissonnette, Joyce Wieland, and Sandra Lahire, developed a complex vision of histories and voices continually pushed to the side of movements fighting for access to basic necessities of survival.

Victoria Brooks is a curator and producer based in Troy, NY. Prior to joining EMPAC (Experimental Media & Performing Arts Centre) in 2013 as curator of time-based visual art, Brooks was a London-based independent curator, co-founding the itinerant curatorial platform The Island, co-curating Serpentine Galleryʼs artist-cinema program, and producing Canary Wharf Screen for Art on the Underground. Together with Evan Calder Williams, she is currently organizing Third Run, a new yearly film journal and colloquium series to be launched in fall 2014.

Evan Calder Williams is a writer, theorist, and artist. He has a doctoral degree from the Literature Department at University of California Santa Cruz, where he wrote a dissertation entitled The Fog of Class War: Cinema, Circulation, and Refusal in Italy’s Creeping’70s. He is the 2013-2014 Fellow at the Center for Transformative Media at Parsons, where is developing a theory of sabotage. He is the author of two books, Combined and Uneven Apocalypse and Roman Letters, has written for Film Quarterly, Mute, La Furia Umana, Viewpoint, and The New Inquiry, and writes the blog Socialism and/or Barbarism.

Preceded by a screening of

Sophie Bissonnette, Martin Duckworth, Joyce Rock, A Wives Tale (CA, 1980)

THE FIRE NEXT TIME — Destroy Yourselves as Our Bosses, Evan Calder Williams & Victoria Brooks from KASK & CONSERVATORIUM on Vimeo.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Möglichkeitsraum (The Blast of the Possible)

Angela Melitopoulos & Bettina Knaup

The Blast of the Possible is a project containing the creation of a temporary performance and lecture platform, a space for exhibiting video and film archive materials belonging to the history of activist media since the 1960s. The design of the platform is based on the idea of an extended postproduction studio in that all functions of montage are spatially presented. This theatrical archive space recalls the archaic function of theatre being a switching panel for different modes of language flows that foster potentials of experimentation, learning and the relation and agency between language-modes. The imaginary developing from an index of the databases and from the materiality of the archival documents will be transformed and preformed through the live energy of performance and speech. ‘Language,’ as Walter Benjamin states, ‘is mediating the immediacy of all mental communication, and if one chooses to call this immediacy magic, then the primary problem of language is its magic.’ Angela Melitopoulos & Bettina Knaup propose to concatenate different languages modes and work on their boundaries with performances that mind the gap between memory and matter. The exhibition becomes a place in that we sense the time quality of mediated images, their historical context, their possible figures and pathologies, their spatial order and their construction and segmentation, their open or closed logic of montage. Through these interventions we can re-read documents and documentation, the construction of representation and identity, the imaginary of the past and the potentialities of becoming.

Angela Melitopoulos studied fine arts with Nam June Paik at the Academy of Arts in Düsseldorf. She has been working with electronic media since 1986 and has created experimental single-channel tapes, video installations, video-essays and documentaries, her work of art often based on research and collaboration with other knowledge spheres like sociology, politics and theory. She has recently been appointed professor in the Media School of the Royal Art Academy in Copenhagen.

Bettina Knaup is a cultural producer with a background in political science, theatre, film, TV studies and gender studies. She has been involved in developing or managing a range of interdisciplinary and transnational cultural projects operating at the interface of arts, politics and knowledge production, including the open space of the International Women’s University (Hanover) and the trans-disciplinary Performing Arts Laboratory, IN TRANSIT (Berlin).

THE FIRE NEXT TIME – Möglichkeitsraum (The Blast of the Possible), Angela Melitopoulos & Bettina Knaup from KASK & CONSERVATORIUM on Vimeo.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

When we act or undergo, we must always be worthy of what happens to us

Ayreen Anastas & Rene Gabri

The militant cinema and image, taken in a more strict sense, have historically tended to push toward the real and toward the truth and toward the overcoming of capitalism, colonialism, and sometimes patriarchy among other things. They have worked to uncover, to lay bare, to expose, to clarify and at times to destroy existing regimes of order and/or truth. Occasionally, there have also been engaged comrades who have chosen the path of militancy as an arena to also investigate the truth claims of the image itself and its production. Of questioning the regimes of images themselves whether as spectacle or as contested fables or fictions. The utopic in the latter camp assumed cinema must be destroyed in the struggle. The more skeptical of this group, (in the philosophical sense not the everyday sense) returned to the cinema as a place of diagnosing the limits and failures of movements, as well as the images movements produced. This film is not about this history and the antinomies of these various modes of militancy in cinema, here reduced to a kind of caricature (quite common in historical accounts). It attempts instead to loiter around the shards and remnants of the processes, struggles and gestures that were produced in these varied forms of militancy in the hopes of discovering the latent forces and insights they may retain for contemporary struggles.

Ayreen Anastas & Rene Gabri work together. Ayreen writes in fragments, and makes films and videos. She is interested in philosophy, literature, the political and the everyday. Rene is interested in the complex mechanisms that constitute the world. He works within the folds of cultural practice, social thought and politics. Ayreen and Rene’s collaborative projects have evolved a great deal through their frequent contributions to the programme at 16Beaver, an artist community that functions as a social and collaborative space in downtown Manhattan, where the group hosts panel discussions, film series, reading groups and more. Ayreen and Rene’s Radioactive Discussion series was a physical counterpart to their fictional Homeland Security Cultural Bureau project. Other collaborations include: Camp Campaign, Artist talk, Radio Active, United We Stand, What Everybody Knows, Eden Resonating, 7X77, Case Sensitive America and more.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

FRIDAY 4 APRIL

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Memories of upheaval and tropical insurrection

Olivier Hadouchi, Stoffel Debuysere, Mathieu Kleyebe Abonnenc

At this stalled and disillusioned juncture in postcolonial history, at a time when many anticolonial utopias have withered into a morass of exhaustion, corruption, and authoritarianism, how can we rethink the past in order to reimagine a more usable future ? If the longing for revolution, the craving for the overcoming of the colonial past and the reclaiming of national identity that shaped the ‘cinemas of liberation’ of the 1960’s is not one that we can inhabit today, then it may be part of our task to set it aside and begin an effort of reimagining other futures for us to dream of. But how can we go beyond the nostalgia for past horizons that still (or once again) seems to occupy our contemporary scope of imagination ? Can an answer be found in the work of the contemporary artists and filmmakers who are attempting to reinvent and redirect the legacies of militant culture and ‘Third cinema’ ? How to position ourselves today in view of this large corpus of historical film works in a context that is radically different but at the same time dauntingly close ? A selection of formally and politically bold films from Latin-America will serve as the starting point for a discussion on the relation between our ‘dead-end’ present, and, on one hand, the old utopian futures that inspired it and, on the other, an imagined idiom of future futures that might reanimate this present and perhaps even engender in it unexpected horizons of transformative possibility.

Olivier Hadouchi is a critic, curator and film historian, based in Paris. He obtained a PhD at the University Sorbonne Nouvelle (Paris 3) on Cinema and Liberation struggles around Tricontinental’s constellation (1966-1975). He has written for various publications such as CinémAction, Third Text, Mondes du Cinéma, La Furia Umana and has curated film programs for Le BAL, Bétonsalon. le Cinématographe de Nantes and la HEAD (Genève).

Mathieu Kleyebe Abonnenc is an artist, curator and researcher interested in exploring the history of the colonial encounter and its effects on memory and identity. Amongst others, he is very concerned to engage with film history and the decolonisation of African states in the 1960s. Abonnenc recently took part in the Paris Triennial in the Palais de Tokyo and in group exhibitions in the Fondation d‘entreprise Ricard (Paris) and the ICA – Institute of Contemporary Art (Philadelphia, USA).

Preceded by a screening of

Santiago Álvarez, Now ! (CU, 1965)

Ugo Ulive, Basta (VE, 1969)

Santiago Álvarez, 79 Primaveras (CU, 1969)

Nicolás Guillén Landrián, Coffea Arábiga (CU, 1968)

Nicolás Guillén Landrián, Desde La Habana ¡1969! Recordar (CU, 1968)

Humberto Solás, Simparelé (CU, 1974)

THE FIRE NEXT TIME — Memories Of Upheaval, Olivier Hadouchi, Mathieu Kleyebe Abonnenc, Stoffel Debuysere from KASK & CONSERVATORIUM on Vimeo.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Splicing the Militant Cinema

Subversive Film (Mohanad Yaqubi & Reem Shilleh)

In 1968, a group of young filmmakers decided to establish a film unit affiliated with the Palestinian Revolution newly active in Amman, Jordan. The unit was called Palestine Film Unit (PFU) and was working with Al Fatah, one of the Palestinian Libation Organization (PLO) factions that adopted armed struggle as the only way to liberate Palestine. When the PFU was established, not only did it furnish the revolution with cinematic vocabularies, but it also addressed the decades old dilemma of invisibility of the Palestinian people and would offer apparatus for reclaiming visibility. At a later time the work of the unit became a major part of the Palestinian revolutionary cinema. This presentation tracks life and work of the PFU and its members as an example of a militant cinema practice in the 1960’s and ‘70’s, when filmmakers believed cinema could change the world.

Subversive Film is a cinema research and production initiative that aims to cast new light upon historic works related to Palestine and the region; to engender support for film preservation; and to investigate archival practices and effects. Other projects developed by Subversive Film to explore this cine-historic field include the digital reissuing of previously-overlooked films, the curating of rare film screening cycles, and the subtitling of rediscovered films. Subversive Film was formed in 2011 and is based in Ramallah and London.

THE FIRE NEXT TIME – Splicing The Militant Cinema from KASK & CONSERVATORIUM on Vimeo.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Dissident Images

Raquel Schefer

In 1982, in the short film Changer d’Image – Lettre à la bien aimée (To Alter the Image), Jean-Luc Godard reflected upon the difficulty to produce an image of change likely to induce and formally represent change. Can an image of change give rise to change? Must an image of change be an altered image? A politics of aesthetics underlays these questions, as they point out to the poetics and politics of the film image, to the intrinsic articulation of its aesthetic and pragmatic dimensions. Representing current class struggle in Southern Europe, Daphné Hérétakis’ Ici rien (2011) and Ramiro Ledo Cordeiro’s Vida Extra (2013) reclaim a poetic political cinema, leading a formal creative synthesis between historical legacy and emergent audiovisual forms which undermines established categories. Daphné Hérétakis and Ramiro Ledo Cordeiro will be present to show their work, to discuss these aporias of image, aesthetics and politics, and to rethink the relationship between art and politics in the context of an open collective debate.

Raquel Schefer is a filmmaker and researcher. She is presently doing a PHD in Cinema Studies at the Université de la Sorbonne-Nouvelle (Paris 3). Politics of representation, remembrance and oblivion, the acts of telling and re-telling, and the non-coincidence between sensorial memory and audiovisual mnemonics are central issues in her work. Historical episodes are approached through personal and familiar narratives, in some cases embedded in the history of Portuguese decolonization.

THE FIRE NEXT TIME — Dissident Images, Raquel Schefer, Ramiro Ledo Cordeiro, Daphné Hérétakis from KASK & CONSERVATORIUM on Vimeo.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Crazy Nigger – Gay Guerilla

CONCERT Julius Eastman

“What I mean by niggers is that thing which is fundamental, that person or thing that attains to a basicness or a fundamentalness, and eschews that which is superficial, or, could we say, elegant… There are 99 names of Allah, and there are 52 niggers.”

– Julius Eastman, Jan 16 1980, Northwestern University

When Julius Eastman took the stage of the concert hall of the Northwestern University to explain the titles of the pieces that he and three other pianists were about to perform, he could not have known that this appearance would be the most lasting statement about his music. Having studied with the likes of George E. Lewis, Morton Feldman and Lukas Foss, all signs pointed towards a bright future for this composer. By 1980 Eastman was performing his music all over Europe and the States and he was an integral part of the thriving Downtown scene in New York, where he recorded with Arthur Russell and Meredith Monk. But for all this promise, his self-destructive behaviour inevitably caught up with him. When he passed away on May 28 1980 in a hospital in Buffalo, the news took more than seven months to reach New York. With the scarce recordings and scores of his music scattered all over the place, attempts to reconstruct Eastman’s output are doomed to remain incomplete. Only fairly recently a selection of his work has been made available, including the trilogy Evil Nigger, Crazy Nigger & Gay Guerilla, which represents in so many ways the intense brilliance of this ‘forgotten minimalist’. These compositions for multiple pianos took the minimalist device of additive process to a whole new structural level, building up immense emotive power through the incessant repetition of rhythmic figures, a composing technique he called ‘organic music’. The titles of the pieces exemplify the rebellious attitude of Eastman, as someone who has always struggled with identity, yet never without casting a new life; someone who has steadfastly eschewed compromise, yet giving rise to a body of work that continues to startle and engage.

in collaboration with art centre Vooruit.

THE FIRE NEXT TIME – Julius Eastman from KASK & CONSERVATORIUM on Vimeo.